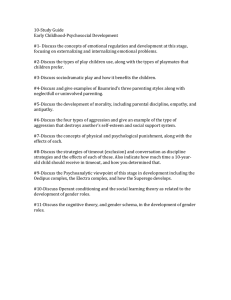

Scenarios The Benefits of Sociodramatic Play For the Young Child

advertisement