Document 16076267

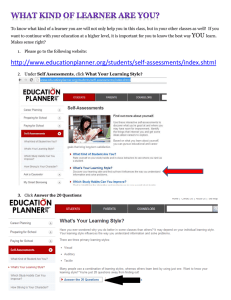

advertisement