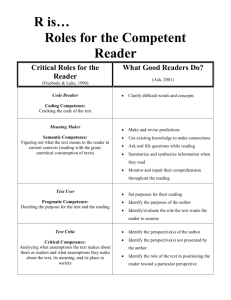

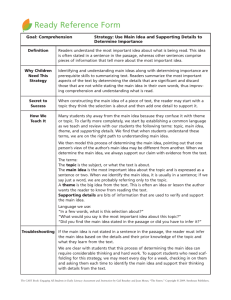

Reading Competence and Goals 1

advertisement