APPLICATION OF THE MULTIPLE STREAMS MODEL TO TRIBAL

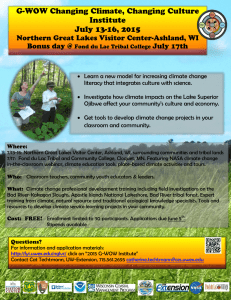

advertisement