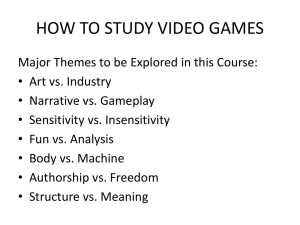

Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION

advertisement