THE ROLE OF ADULT ATTACHMENT STYLES AND PERSONALITY TRAITS IN

MULTIDIMENSIONAL PERFECTIONISM

A Thesis

Presented to the faculty of the Department of Psychology

California State University, Sacramento

Submitted in partial satisfaction of

the requirements for the degree of

MASTER OF ARTS

in

Psychology

by

Erika R. Call

SPRING

2012

© 2012

Erika R. Call

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

ii

THE ROLE OF ADULT ATTACHMENT STYLES AND PERSONALITY TRAITS IN

MULTIDIMENSIONAL PERFECTIONISM

A Thesis

by

Erika R. Call

Approved by:

, Committee Chair

Lawrence S. Meyers, Ph.D.

, Second Reader

Phillip Akutsu, Ph.D.

,

Third Reader

Tim Gaffney, Ph. D.

_____________________________

Date

iii

Student: Erika R. Call

I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University

format manual, and that this thesis is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to

be awarded for the thesis.

__________________________, Graduate Coordinator

Jianjian Qin, Ph.D

Department of Psychology

iv

___________________

Date

Abstract

of

THE ROLE OF ADULT ATTACHMENT STYLES AND PERSONALITY TRAITS IN

MULTIDIMENSIONAL PERFECTIONISM

by

Erika R. Call

Adult attachment and personality traits can impact an individual’s attributions of

perfectionism. This study explored the predictor variables of adult attachment (anxious

and avoidant) and personality traits on the criterion variable of multidimensional

perfectionism as measured by four dimensions of perfectionism; Adaptive, Maladaptive,

High Standards, and Order, subscales that divide perfectionism into adaptive and

maladaptive perfectionists. Adaptive perfectionists manifest the positive qualities of

perfectionism while maladaptive perfectionists manifest the negative qualities. A

multiple regression analysis yielded four significant prediction models of perfectionism.

The models indicate that there is a significant relationship that exists between the

weighted linear composite of the independent variables as specified by the model and

each criterion variable of perfectionism. Adult attachment did not significantly predict

any dimension of perfectionism. The results suggest that personality traits are a potential

implication in the formulation of these four perfectionism dimensions.

, Committee Chair

Lawrence S. Meyers, Ph.D.

_____________________________

Date

v

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to give my sincere gratitude to my thesis chair and mentor, Dr. Lawrence

Meyers. Dr. Meyers worked with me tirelessly and patiently throughout this entire

process. His help and constructive input were invaluable in the completion of this thesis.

Dr. Meyers, I am grateful for all of your support and direction during my time at

Sacramento State. I would like to thank my committee members, Dr. Gaffney, and Dr.

Akutsu for their guidance throughout the writing process. I would also like to thank my

incredibly supportive parents, my sisters, and my fiancé. Thank you for your continued

encouragement and support when I was faltering. Above all, I would like to thank God

for blessing me with the opportunity to pursue my passion for higher education.

vi

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………….

vi

List of Tables……………………………………………………………………...

viii

Chapter

1. INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………..

1

Philosophical Perfectionism……………………………………………...

1

Perfectionism in Early Psychology……………………………………….

3

Perfectionism in Personality………………………………………………

6

Perfectionism in Adult Attachment……………………………………….

8

Perfectionism as a Multidimensional Construct………………………….. 10

The Present Study………………………………………………………… 13

2. METHOD……………………………………………………………………… 16

Participants……………………………………………………………….. 16

Measures…………………………………………………………………... 16

Design and Procedure……………………….…………………………….. 22

3. RESULTS……………………………………………………………………… 24

Descriptive Statistics……………………………………………………… 24

Reliability Analysis……………………………………………………….. 25

Principal Components Analyses…………………………………………... 29

Multiple Regression………………………………………………………. 35

4. DISCUSSION………………………………………………………………….. 45

Limitations………………………………………………………………… 50

References…………………………………………………………………………. 52

vii

LIST OF TABLES

Tables

Page

1. Descriptive Statistics of Demographic Information for the

Participants……………………………………………………….......

25

2. Descriptive Statistics for the Inventories…………………………………

29

3. Structure Coefficients for the Almost Perfect Scale-Revised Items….....

31

4. Structure Coefficients for the Subscales of the Relationship Scales

Questionnaire…………………………………………………………

34

5. Standard Regression Results for Predicting Scores of Maladaptive

Perfectionism……………………………………………………........

37

6. Standard Regression Results for Predicting Scores on the High Standards

Subscale of Perfectionism……………………………………………

39

7. Standard Regression Results for Predicting Scores on the Order Subscale

of Perfectionism………………………………………………………

41

8. Standard Regression Results Predicting Scores for Adaptive

Perfectionism……………………………………………………….....

viii

43

1

Chapter 1

INTRODUCTION

Philosophical Perfectionism

The concept of perfectionism has been explored as far back as ancient philosophy.

Historically, perfectionism has been a maximizing morality which instructed individuals

to achieve the greatest perfection that they can (as cited in Hurka, 1993, p. 56). Aristotle

was among the first to establish a theory on perfectionism, which was a key component in

his political theory. Aristotle examined perfectionism from a teological perspective, with

a good and evil component. Aristotle believed the path to perfection should be selfsatisfying so each person could achieve it on his/her own. He said that if perfection were

entirely self-sufficient, there would be little scope for consequentialist judgments (as

cited in Hurka, 1993, p. 59). Consequentialist judgments presuppose that human goods

are commensurable in a way that seemingly permits “greater goods” (Grisez, 1978, p.

21). He argued that if each person always knew they would be excellent on a given task,

then his/her failure to achieve would be entirely attributed to choosing the wrong task.

Aristotle distinguishes three concepts about perfection(ism); that is, something is perfect

when it is complete (no addition or enhancement would improve the quality of the

object); when it is so good that nothing of the kind could be better; and when it has

attained its purpose (when an object or concept has successfully fulfilled its intention).

For human beings the ultimate good or happiness consists in the pursuit of perfection, the

2

full attainment of their natural function, which Aristotle analyzes as the activity of the

soul according to reason (or not without reason). In De Anima, Aristotle’s

belief about perfectionism was in opposition to the subjective relativism of Protagoras,

who believed that what was good and evil is defined by whatever an individual happened

to desire. Like Plato, Aristotle maintained that good was objective and independent of

human wishes. Moreover, Aristotle rejected Plato’s theory that good was defined in

terms of a transcendent form of the good, holding instead to the belief that good and evil

are in a way relative to its natural end (as cited in Durrant, 1993, p. 162).

Later, Thomas Aquinas examined perfectionism in the Christian context. In the

Summa Theologica (1265-1274), he explained his theory on perfectionism was similar to

that of Aristotle’s last two concepts: which is so good that nothing of the kind could be

better; which is attained its purpose. From this, he distinguished a two-fold perfection:

when a thing is perfect in substance; and when it perfectly serves its purpose. Aquinas

acknowledged that perfection existed in the world, but not within the individual. He

argued that the only perfection was God. In his Summa Theologica, he wrote that God is

distinguished from other beings because of God’s complete actuality. God lacks nothing;

therefore He is perfect. Aquinas argued that human existence could not experience

perfection; the goal of human existence is a union and eternal fellowship with God, and

this goal is only achieved through an event where an individual experiences perfect

unending happiness by seeing the very essence of God. Whereas Thomas Aquinas

argued that human existence could not reach perfection, only God was perfect, Immanuel

Kant believed the theory of perfection did live amid human existence.

3

Immanuel Kant had equated perfection with morally good will and argued that an

individual could acquire this good will from one moment to the next. Aristotle did not

believe that perfection was entirely self-sufficient, but Immanuel Kant supported this

premise. Kant argued that when an individual is faced with wrongdoing, we could

always regard it as though the individual had fallen into it directly from a state of

innocence (as cited in Hurka, 1993, p. 36). For Kant, an individual’s perfection depends

entirely on his/her choices, which makes much of the point of consequentialism irrelevant

(as cited in Hurka, 1993, p. 69). In Kant’s Critique of Judgment (1790), he wrote about

perfection. Kant described perfectionism as; objective and subjective, qualitative and

quantitative, perceived as clearly and obscurely, essentially encompassing every aspect of

being. Kant’s description of perfection applies to everything in nature.

Perfectionism in Early Psychology

Fairly early on in the field of psychology, Sigmund Freud introduced the

discipline to his theory of the personality. In 1923, Freud introduced three components of

the personality. The preconscious, described as the antechamber to the conscious,

containing relatively accessible material. The conscious, described as what we are aware

of at any given moment. Finally, the unconscious, described as the site of relatively

irretrievable material, some of which may be repressed. These three components were

unexplored dimensions of the personality. Within the proposed component of the

personality, the subconscious, there were three underlying dimensions: id, ego, and

superego. It is within this theory of personality that the concept of perfectionism was

first introduced to the field of psychology.

4

Freud argued that the ego is extremely objective and it operates according to the

“reality principle” and deals with the demands of the environment, and it regulates the id.

The id holds all the desires of the individual; it is the pleasure principle component of the

personality. Perfection is an attribute of the superego. The superego represents the

values and standards of an individual’s personality, it acts as an internal judge, and it

punishes the ego, which leads to feelings of pride and heightened self-esteem. The

superego is a characteristic of the personality that strives for perfection (as cited in

Thorne & Henley, 2005, p. 435). This idea that perfection is a component of the

personality was later expanded in the work of Karen Horney.

In her theory of neurosis, Karen Horney established a list of ten basic needs that

humans require to succeed in life. The need for perfection was one of these ten needs.

The striving for perfection was indicative of a successful life according to the theory.

Horney (1939) argued that while many are driven to perfecting their lives in the form of

increasing well being, there are others that may display a fear of being slightly flawed,

which could be reflective in neurosis. This stringent need for perfection above all else to

the point of unacceptable failure could be harmful to an individual. This is presumably

where the negative connotation associated with perfectionism began. Karen Horney

began to associate her studies on narcissism with perfectionism acting as an underlying

personality trait. Horney further studied narcissism and neurosis in her work, Neurosis

and Human Growth: The Struggle Toward Self-Realization (1950). She summarized her

neurotic solutions to the stresses of life (expansive, self-effacement, resignation) and one

of them, “expansive solution”, was composed of a combination of narcissistic,

5

perfectionistic, and arrogant-vindictive approaches to life. Her perspective on narcissism

and perfectionism being related to the construct of the personality was shared with fellow

psychoanalyst, Alfred Adler. Both Karen Horney and Alfred Adler believed that the

development of perfectionism begins in childhood, and it is not entirely reactive and

influenced by parental factors or cultural pressures to be perfect.

While Sigmund Freud and Karen Horney were performing their research on

personality, Alfred Adler was also exploring the human mind and developing his own

theory. His Individual Psychology approach explored the individual differences of the

personality, focusing as previous psychologists before him on the neurotic individual.

The importance of perfectionism’s effect in helping people become anxious, depressed,

and otherwise emotionally disturbed was pointed out by pioneering cognitive

psychologist, Alfred Adler (1926, 1927).

Adler (1956) and Horney (1950) regarded the development of perfectionism as

the child’s active response to feelings of inferiority and neurotic difficulties. In The

Neurotic Disposition (1956) Adler suggested that striving for perfection is as innate and

intrinsic necessity for human development. Adler (1956) suggested that it is very normal

for individuals to strive for perfection; they set goals that are difficult to attain among

other things, but the majority of these goals are realistic and modified at times as needed.

Adler (1956) asserted that perfectionism arises, in part, from a neurotic need to please

significant others, the fear of failure, and characterologically based anxiety and selfdoubt.

6

Adler was among the first to argue that perfectionism was not solely a negative

personality trait and in an essence not a unidimensional personality trait, it had varying

dimensions. A distinction between “normal” (i.e., adaptive) and “neurotic” (i.e.,

maladaptive) perfectionism was suggested by Adler (1956) prior to psychometric

measures of perfectionism were established. In this work he suggested that individuals

who are maladaptive perfectionists are unable to experience pleasure from his/her labor.

Maladaptive perfectionists have unrealistically and unreasonably high standards of

themselves, and a sense of self-worth dependent on their performance. Individuals who

are adaptive perfectionists are able to experience satisfaction or pleasure. Their goals are

attained for the enhancement of society, they have achievable high standards that are

matched to the individual’s limitations and strengths, and they strive for success (Adler,

1956). The work by Adler was fundamental in the study of perfectionism and researchers

that would follow him would use his work as a foundation for their research.

Perfectionism in Personality

As previous researchers have already established, there is a uniqueness to

personality, as each individual’s personality varies (Adler, 1956). Hollender (1965)

described the perfectionist as a person who sets rigid, unrealistically high standards and

engages in an all-or-none mentality when evaluating his or her performance. Hollender

(1965) went on to describe perfectionists as overly sensitive to rejection and excessively

concerned with approval from others. Hollender (1965) goes on to explain that due to the

lack of self-competence, they in turn depend on other people’s evaluations to feel secure.

Perfectionism as a personality characteristic has been implicated in studies as being a

7

causal factor for a multitude of negative affect states (e.g. depression, self-esteem) and

neuroticism (Flett, Hewitt, & Dyck, 1989). Recently, perfectionism has been studied

with multiple personality dimensions.

The most widely recognized and applied personality model is The Big Five model

of personality. It has been accepted as higher order factors that help to characterize and

better understand other personality constructs (John & Srivastava, 1999). Extraversion

assesses traits such as sociability, activity, assertiveness, and positive emotionality.

Conscientiousness describes task and goal-directed behavior such as organizing and

prioritizing tasks. Agreeableness refers to traits like altruism, trust, and modesty.

Neuroticism refers to negative emotions like feeling anxious, nervousness, and sadness.

Finally, openness to experience assesses attributes such as creativeness, originality, and

imaginativeness.

Prior research using the Big Five with different perfectionism scales generally

found the same results. Adaptive perfectionism was found to be positively related to

conscientiousness (Dunkley, Blankstein, Zuroff, Lecce, & Hui, 2006; Parker & Stumpf,

1995; Stumpf & Parker, 2000) and openness to experience (Dunkley et al., 2006), but

negatively associated with neuroticism (Dunkley et al., 2006). Maladaptive

perfectionism was positively related to neuroticism (Dunkley et al., 2006; Hewitt, Flett,

& Blankstein, 1991; Parker & Stumpf, 1995; Stumpf & Parker, 2000), but negatively

related to extraversion and agreeableness (Dunkley et al., 2006). Additional variables

that may relate to maladaptive perfectionism are disagreeableness, neuroticism, and

extraversion, which are subsumed by what has come to be known as the Dark Triad

8

(Paulhus & Wiliams, 2002). The Dark Triad personality describes three unfavorable

personality constructs, Narcissism, Psychopathy, and Machiavellinism. According to

Paulhus & Williams (2002) Machiavellians and narcissists exhibit a more maladaptive

personality. The Dark Triad personality shares one commonality with the Big Five

personality construct, namely, low agreeableness.

These results provide consistency in the findings across the studies regarding the

positive associations between adaptive perfectionism and conscientiousness as well as

between maladaptive perfectionism and neuroticism (Ulu & Tezer, 2010). There is,

however, little evidence in the literature (Dunkley et al., 2006) regarding the relationship

between adaptive and maladaptive perfectionism with various other personality traits.

Perfectionism in Adult Attachment

Alfred Adler (1956) and Karen Horney (1950) were the first to argue that

perfectionism begins in childhood. They explained that the development of

perfectionism is the child’s active response to feelings of inferiority and neurotic

difficulties. Hewitt and Flett (1991) built their model of perfectionism on this perception

that the foundation of perfectionism begins in childhood. Hewitt and Flett (1991) argued

that the role of external pressures (both parental and social) is reflected clearly in the

development of socially prescribed perfectionism. The lack of parental responsiveness

will also contribute to insecure attachment styles associated with socially prescribed

perfectionism. Flett and Hewitt (2002, p. 110) claimed that the development of

perfectionism requires that the child has to actively translate those pressures by

internalizing the demands into pressures on the self (i.e., self-oriented perfectionism) or

9

externalizing the demands in the form of pressures on others (i.e. other-oriented

perfectionism).

Attachment theory (Ainsworth & Bowlby, 1991; Bowlby, 1969), which was

originally sought to understand infant-mother attachment, has recently grown and been

applied to the study of adolescent and adult attachment styles and how they function in

their current relationships (Hazan & Shaver, 1987). According to attachment theory

(Bowlby, 1988), the quality of early experiences with parental caregivers shapes the

development of an individual’s general orientation to intimate peer relationships. He

proposed that the negative experiences that individuals have early in life with their

parental figures (i.e. excessive criticism, overindulgence, and indifference) are more

likely to increase an insecure adult attachment orientation. On the other hand, positive

experiences early in an individual’s life such as supportive and autonomy-encouraging

interactions with parental figures increase a secure adult attachment orientation. Shaver

and Hazan (1993) demonstrated that adult attachment styles have been shown to be

related to jealousy, paternal drinking, sexual activity, relationship satisfaction, conflict

styles, coping responses, neuroticism, and depression among other things.

Adult attachment has more recently been studied as a two-dimensional model. The two

dimensions of anxiety (model of self) and avoidance (model of other) are assumed to

underlie variation in adult attachment orientation (Simpson, Rholes, & Nelligan, 1992).

There has been a substantial amount of research literature that has shown that these two

underlying dimensions are directly related to cognitive processes, affect regulation

strategies, and interpersonal behaviors (Lopez & Brennan, 2000). Griffin and

10

Bartholomew (1994) originally proposed a scale that assessed four categories of

attachment that were factor analyzed to represent two dimensions of adult attachment,

anxiety and avoidance. Previous research has confirmed that the four attachment

categories can be reliably measured, that a two-dimensional structure underlies the four

patterns as hypothesized, and that different methods of assessment converge as expected

to support these findings (Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991; Griffin & Bartholomew,

1993). Griffin and Bartholomew (1994) recognized that most individuals exhibit

elements of more than one attachment pattern.

Perfectionism as a Multidimensional Construct

There have been several studies that have explored Adlerian explanations for

significant differences between adaptive and maladaptive perfectionism (Ashby &

Kottman, 1996; Kottman & Ashby, 1999). Past research suggests that there is a

significant distinction between adaptive and maladaptive perfectionism based on how

perfectionists use their perfectionism. From an Adlerian perspective, the adaptive

perfectionist, who experiences less distress related to perfectionism and is striving for

high standards, may be appropriately pursuing superiority (Flett & Hewitt, 2002, p. 83).

In contrast, the maladaptive perfectionist may pursue high standards to avoid feelings of

inferiority. This avoidance may be manifested in the need to out perform other

individuals and may be directly related to a family dynamic where love and acceptance

are based on performance (Flett & Hewit, 2002, p. 83).

Previous researchers have identified two separate high-order dimensions of

perfectionism, the most prominent being “normal and positive (adaptive), or neurotic and

11

dysfunctional (maladaptive)” perfection (Hamachek, 1978). The “adaptive”

perfectionists reported feeling satisfied when their standards were achieved. They have

preferences for personal competence, and expectations for a strong performance in

academics and work, and they set high personal goals. These characteristics are

positively correlated with variables such as active coping, higher self-esteem,

achievement, and conscientiousness (Parker, 1997; Rice & Lapsley, 2001).

The second high-order dimension of perfectionism is maladaptive perfectionism.

The “maladaptive” perfectionists are rarely satisfied, if ever, and strongly critique

themselves on all tasks. The maladaptive perfectionists are typically described as having

excessive concerns about making mistakes, self-doubt, and perceptions of failure to attain

personal standards (Frost, Heimberg, Holt, Mattia, & Neubauer, 1993). The common

characteristic between the adaptive and maladaptive aspects of perfectionism appears to

be the concern for high personal standards. After Hamchek’s initial identification of the

positive and negative aspects of perfectionism, several other attempts have been made to

identify positive aspects that led to new conceptualizations of the construct.

Perfectionism has proven to be a difficult construct to define. Frost, Marten,

Lahart, and Rosenblate (1990) attempted to define the construct of perfectionism with the

establishment of the Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (MPS). This measure

produced five interrelated subscales that could be summed to create one unidimensional

score of perfectionism. These subscales measure the extent to which an individual (a) is

concerned over making mistakes, (b) sets high personal standards, (c) feels criticized by

12

his or her parents, (d) feels that his or her parents have high expectations for him or

herself, and (e) doubts his or her ability to perform actions.

The first known qualitative study on these concepts was performed by Slaney and

Ashby (1996) who had participants explain their comprehension of perfectionism as well

as their own experiences. Slaney and Ashby (1996) identified the structured interviews

of the participants and found that there were three universal characteristics of

perfectionism: (a) having high standards for performance, (b) having a sense of

discrepancy between standards and performance that creates distress, and (c) being neat

and orderly. They factor analyzed their subscales and created the Almost Perfect ScaleRevised (2001) and were able to conclude that the high standards subscale measures

adaptive perfectionism, while the discrepancy subscale measures maladaptive

perfectionism. From this, researchers (Rice et al., 1996) have been able to divide

perfectionists into (a) adaptive perfectionists who seem to manifest positive qualities, and

(b) maladaptive perfectionists, who seem to manifest negative qualities of perfectionism.

The topic of perfectionism and its multidimensional construct has received increasing

concentration in the psychology literature. There has been a multitude of interest in

exploring perfectionism and more recently, there has been the development of useful

multidimensional conceptualizations of perfectionism (Frost, Marten, Lahart, &

Rosenblate, 1990; Hamachek, 1978; Hewitt & Flett, 1991; Slaney, Rice, Mobley, Trippi,

& Ashby, 2001).

13

The Present Study

Prior research has examined the characteristics of adaptive and maladaptive

perfectionism in relation to parental attachment (Rice & Mirzadeh, 2000), the personality

characteristics of a fully functioning individual (Ashby, Rahotep, & Martin, 2005), and

self-esteem (Rice, Ashby, & Preusser, 1996). Perfectionism in relation to personality

characteristics has been studied primarily with the Big Five Personality Characteristics

(Costa &McCrea, 1992). Maladaptive perfectionism has been repeatedly associated with

a multitude of psychological problems like decreased self-esteem, depression, anxiety,

eating disorders, dysfunctional attitudes, and substance abuse (Blatt, 1995). An

individual’s level of attachment security may function to either lessen or intensify the

negative effects of maladaptive perfectionism on self-esteem; whereas individuals who

recognize that they have high levels of attachment security, self-doubt appears to have a

less adverse impact on self-esteem; for individuals with low levels of attachment security,

self-doubt was more directly related to low self-esteem (Rice & Lopez, 2004).

Perfectionism in relation to adult attachment and certain personality

characteristics, The Big Five (Costa & McCrea, 1992) has been studied separately,

creating two independent lines of study. However, by considering the impact of

attachment style in the development of the personality (Bowlby, 1969) and the numerous

studies on the Big Five personality traits, it is clear there is room for further investigation

on various personality traits, adult attachment, and perfectionism.

The “Dark Triad” is a newly developed construct proposed by Palhaus and

Williams (2002) that describes three unfavorable personality constructs, Narcissism,

14

Psychopathy, and Machiavellianism. Narcissism is described as attention-seeking

behaviors, excessive self-focus, and exploitation in interpersonal relationships (Millon &

Davis, 1996). Machiavellian people are characterized to be more intelligent than their

non-Machiavellian counterparts, with these individuals displaying deceit, flattery, and

emotional detachment to manipulate social and personal interactions (Jakobwitz & Egan,

2005). Psychopathy (in the non-clinical setting) is characterized as an individual with

low empathy and anxiety and with high impulsivity and thrill seeking

mannerisms (Palhaus & Williams, 2002). All three aspects of the Dark Triad personality

have been found to correlate negatively with agreeableness, with high psychopathy scores

correlating with low neuroticism, and high Machiavellianism and psychopathy

scores correlating with low conscientiousness. There is a lack of research that

investigates the Dark Triad personality in relation to adult attachment and the current

study seeks to examine the concept.

Individuals who exhibit high levels of adult attachment anxiety have reported

strong fears of rejection and abandonment in their intimate peer relationships and they are

more prone to being easily overwhelmed by negative emotions. Individuals who exhibit

high levels of avoidance have reported experiencing discomfort with intimacy and

closeness, along with stronger desires for interpersonal distance and self-sufficiency; they

are also more likely to suppress negative emotions (Rice & Lopez, 2004). Mikulincer

(1995) demonstrated that individuals with low avoidance and low anxiety in their adult

attachment orientations demonstrate a more positive, cohesive, and integrated self-

15

structure and have a greater tolerance for uncertainty and are less likely to become

vulnerable to depression.

Prior research has focused primarily on the role of anxiety and avoidance

dimensions of adult attachment in maladaptive perfectionism. Results have shown that

anxious and avoidant adult attachment styles are positively related with maladaptive

perfectionism (Rice & Mirzadeh, 2000). The purpose of the current study is to

investigate the role of anxiety and avoidance dimensions of adult attachment and the

“Dark Triad” personality traits in conjunction with various other personality traits in

adaptive and maladaptive dimensions of perfectionism. I hypothesize that lower

attributions of the Dark Triad personality and lower attributions of both anxiety and

avoidance adult attachment dimensions will be predictive of adaptive perfectionism

in an individual, while higher attributions of the Dark Triad personality and higher

attributions of both anxiety and avoidance adult attachment dimensions will be predictive

of maladaptive perfectionism.

16

Chapter 2

METHOD

Participants

The participants for this study were 192 introductory psychology undergraduate

students at California State University, Sacramento. The current sample consisted almost

exclusively of female students (37 males, 154 females). There were 73 White

Americans, 26 Latinos, 17 African Americans, 60 Asian Americans, and 16 others who

did not choose to disclose their ethnicity. Participants were rewarded with one hour of

participation credit towards satisfying their lower division course criteria. The

participants ranged in age from 18 to 50 years (M = 21.3, SD = 4.53).

Demographic information collected from participants included their current

socioeconomic status. There were 37 individuals from a self-reported lower class, 148

self-reported middle class, 6 self-reported upper class, and 1 individual who did not

choose to disclose his/her socioeconomic status.

Measures

Participants were supplied with all materials need to complete the questionnaire

packets. The measures, along with what they intended to measure are presented below.

The Relationship Scales Questionnaire

The Relationship Scales Questionnaire (Griffin & Bartholomew, 1994) was used

to measure an individual’s adult attachment dimensions (anxiety, avoidance). The

17

measure consisted of 30 items in a self-report questionnaire (e.g., “I often worry that

romantic partners wont want to stay with me”), which were derived from Hazan

and Shaver’s (1987) three-category model of attachment, Bartholomew and Horowitz’s

(1991) four attachment paragraphs and Collins and Read’s (1990) Adult Attachment

Scale. This measure utilizes a 7-point response scale (1 = Not at all like me and 7 = Very

much like me) to assess responses to each item. The items were then used to categorize

participants into of one of four attachment styles (Secure, Preoccupied, Dismissing,

Fearful).

Previous research has confirmed the four attachment prototypes can be reliably

measured and that a two-dimensional structure (model of self: anxiety, model of other:

avoidance) underlies these four patterns (Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991; Griffin &

Bartholomew, 1993). The two underlying dimensions are derived by linear combinations

of the four prototypes. Griffin and Bartholomew (1993) proposed two equations, the self

model (anxiety) is derived by adding the ratings of the patterns defined by positive self

models (the secure and dismissing) and subtracting the ratings of the patterns defined by

negative self models (the fearful and preoccupied), the other model (avoidance) is

derived by adding together an individual’s scores on the patterns hypothesized to

represent positive other models (the secure and preoccupied) and subtracting the scores

on the patterns hypothesized to represent negative other models (the dismissing and

fearful patterns). Scores on the secure and dismissing subscales ranged from 5-25, and

scores on the preoccupied and fearful subscales ranged from 4-20. The internal

consistency reported for the Relationship Scales Questionnaire had a Cronbach’s

18

coefficient alpha of .77 (Griffin & Bartholomew, 1994). All studies by Bartholomew and

Griffin (1994) have reported smaller than necessary sample sizes for establishing

measurement norms, and thus there are no previously reported norms for the inventory.

The Narcissistic Personality Inventory

The Narcissistic Personality Inventory (Raskin & Hall, 1979) is one of the most

widely used measures for assessing the trait of narcissism and the version used here is the

most common one used in the current literature. It consisted of 40 forced-choice items

(e.g., “I have a natural talent for influencing people” or “I am not good at influencing

people”). Higher scores on this scale are indicative as being representative of a more

narcissistic individual. The internal consistency reported for the Narcissistic Personality

Inventory had a Cronbach’s coefficient alpha of .83 (Raskin & Hall, 1979).

Levenson Psychopathy Scale

The Levenson Psychopathy Scale (Levenson, 1995) is used in the literature to

recognize the psychological traits that represent psychopathy. It consisted of 26 items

(e.g., “people who are stupid enough to get ripped off usually deserve it”) and utilizes a

4-point response scale (1 = strongly disagree and 4 = strongly agree). Higher scores

indicate an individual possess more of psychopathy (sociopath) mannerisms. It is

currently used in the literature as a reliable form of assessing psychopathy. The internal

consistency reported for the Levenson Psychopathy Scale was a robust .82 coefficient

alpha (Levenson, 1995).

19

Mach-IV Scales

The Mach-IV Scales (Christie & Geis, 1970) are used to assess Machiavellianism, a

personality trait that characterizes the manipulation and exploitation of others with a selfinterest and deception focus. It consists of 20 items (e.g., “it is hard to get ahead without

cutting corners here and there”) and utilizes a 5-point response scale (1 = strongly

disagree and 5 = strongly agree). Scores on this scale range from 0 to 100. Higher

scores indicate a higher degree of Machiavellianism. It is one of the most reliable scales

for assessing Machiavellianism. The Mach-IV Machiavellianism scale produced a norm

split-half reliability of .79 (Christie & Geis, 1970).

Positive and Negative Affect Scales

The Positive and Negative Affect Scales (PANAS) Scales (Watson, Clark, &

Tellegen, 1988) were used to assess positive affect and negative affect. It consisted of 20

one-word items, 10 items assessed positive affect (e.g., “interested” and “excited”) and

10 items assessed negative affect (e.g., “irritable” and “distressed”). The scale utilizes a

5-point response scale (1 = very slightly or not at all and 5 = extremely) to assess each

item. Scores on this scale range from 10 to 50. Higher scores on the positive affect

subscale indicate a higher amount of positive affect. Higher scores on the negative affect

subscale indicate a higher amount of negative affect. It is one of the most reliable scales

for assessing positive and negative affect of an individual and used in current research

literature. The internal consistency reported for these scales had a coefficient alpha of .88

for the positive affect scale and coefficient alpha of .87 for the negative affect scale

(Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988).

20

Self-Esteem Rating Scale

In order to assess self-esteem, the Self-Esteem Rating Scale (Nugent & Thomas,

1993) was chosen for measurement. It consisted of 40 items (e.g., “I feel that people

would not like me if they really knew me”) and utilizes a 7-point response scale (1 =

never and 7 = always). Higher scores on this measure are indicative of an individual

having higher self-esteem, where lower scores on this scale indicate an individual who

has lower self-esteem. It is not used as often as other self-efficacy scales due to its length

but the literature has shown that this scale has excellent internal consistency.

The internal consistency reported for the scale had a robust Cronbach’s coefficient alpha

of .97 (Nugent & Thomas, 1993).

Physical Self-Efficacy

In order to assess self-efficacy, the Physical Self-Efficacy (Ryckman, Robbins,

Thornton, & Cantrell, 1982) measure was used. The measure consisted of 22 items (e.g.,

“Sometimes I do not hold up well under stress”) and utilizes a 6-point response scale (1 =

strongly agree and 6 = strongly disagree). Higher scores on this measure indicate a

greater amount of self-efficacy that an individual possesses, whereas lower scores on this

measure indicate an individual has lower self-efficacy. It has excellent internal

consistency with a Cronbach’s coefficient alpha of .81, and a test-retest of .80 (Ryckman

et al., 1982). It also has excellent concurrent validity in the published literature

(Ryckman et al., 1982).

21

Satisfaction with Life Scale

In order to assess life satisfaction, the Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener,

Emmons, Larson, & Griffin, 1985) was used. It consisted of 5 items (e.g., “In most ways

my life is close to my ideal”) and utilizes a 7-point response scale (1 = strongly disagree

and 7 = strongly agree). Higher scores indicate an individual has higher attributions of

life satisfaction, whereas lower scores on this measure indicate lower attributions of life

satisfaction. It is one of the shortest scales used to measure the construct, but one of the

most widely used in the current research literature (Ulu & Tezer, 2010). It has a high

reported internal consistency with a Cronbach’s coefficient alpha of .88 (Diener et al.,

1985).

The Duttweiler Internal Control Index

In order to assess internal locus of control, one of the most widely used measures

on this trait was used in the current research, The Duttweiler Internal Control Index

(Duttweiler, 1984). The measure consisted of 28 items (e.g., “I consider different sides

of an issue before making any decisions”) and utilizes a 5-point response scale (1 =

rarely less than 10% of the time and 5 = usually more than 90% of the time). The

Duttweiler Internal Control Index measures an individual’s internal locus of control,

autonomy, self-confidence, and resistance to social influences. Higher scores on this

measure are equivalent to a higher internal locus of control, whereas lower scores on this

measure indicate a lower internal locus of control. This measure has been reported with

an internal consistency of .85 as measured by coefficient alpha (Duttweiler, 1984). It is

commonly cited in the research literature and has good construct validity by means of the

22

Mirels’ Factor I of the Rotter I-E scale, with correlations between the two indices being

significant (Duttweiler, 1984).

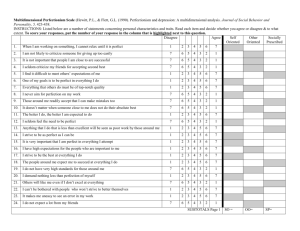

The Almost Perfect Scale-Revised

The study also utilized the Almost Perfect Scale-Revised (Slaney, Rice, Mobley,

Trippi, & Ashby, 2001) which consists of 23 items (e.g., “I often feel disappointment

after completing a task because I know I could have done better”) and utilizes a 7-pont

response scale (1 = strongly disagree and 7 = strongly agree) on items reflecting one of

three independent factors (Discrepancy, High Standards, and Order) derived from a factor

analysis on varying multidimensional perfectionism scales (Frost, Heimberg, Holt,

Mattia, & Neubauer, 1993; Suddarth & Slaney, 2001).

Slaney et al. (2001) concluded the high standards subscale measured adaptive

perfectionism, while the discrepancy subscale measured maladaptive perfectionism. Rice

et al. (1996) were able to divide perfectionists into (a) adaptive perfectionists who

manifest the positive qualities of perfectionism, and (b) maladaptive perfectionists who

manifest the negative qualities of perfectionism. The measure had good internal

consistency producing a Cronbach’s coefficient alpha of .85 (Slaney et al., 2001).

Design and Procedure

The current study used a correlation design to explore the effect that the

dimensions of adult attachment (anxiety, avoidance) and the “Dark Triad” (Narcissism,

Psychopathy, Machiavellianism) personality, in conjunction with other personality

characteristics (positive affect, negative affect, self-esteem, self-efficacy, life satisfaction,

locus of control) had on the multidimensional (adaptive, maladaptive) construct of

23

perfectionism. Participants voluntarily signed up for the research study with the

incentive that they would receive one hour of research participation credit towards

satisfying the Psychology department’s requirement for lower division introductory

courses.

Each participant was provided a packet of materials that contained ten of the

measures mentioned above and a measure to collect demographic information. The

demographic information collected consisted of age, gender (male, female), ethnicity

(Caucasian, African American, Hispanic/Latino, Asian American, Other), and

socioeconomic status (lower class, middle class, upper class). The order of presentation

of the scales in this packet of materials was the following Duttweiler Internal Locus of

Control Index, Satisfaction with Life Scale, Physical Self-Efficacy Scale, Self-Esteem

Rating Scale, PANAS Scales, Mach-IV, Levenson Psychopathy Scale, Narcissistic

Personality Inventory, Relationship Scales Questionnaire, the Almost Perfect ScaleRevised, and the demographic information page.

24

Chapter 3

RESULTS

Descriptive Statistics

One hundred and ninety-two introductory psychology undergraduate students at

California State University, Sacramento participated in the current research in order to

study the dimensions of adult attachment (anxiety and avoidance) and the “Dark Triad”

personality, in conjunction with other personality characteristics on the multidimensional

construct of perfectionism (adaptive and maladaptive).

The 192 undergraduate students (37 males and 154 females) who participated in

this study varied in age from 18 to 50 (M = 21.3, SD = 4.53). There were 73 White

Americans, 26 Latinos, 17 African Americans, 60 Asian Americans, and 16 others who

did not choose to disclose their ethnicity. There were 37 lower class, 148 middle class, 6

upper class, and 1 individual who did not choose to disclose his/her socioeconomic

status. Please refer to Table 1 below for the full descriptive statistics on participants in

this study.

25

Table 1

Descriptive Statistics of Demographic Information for the Participants

Variable

Frequency

Percent

Male

37

19.3

Female

154

80.2

Caucasian

73

38.0

Hispanic

26

13.5

African American

17

8.9

Asian American

60

31.3

Other

16

8.3

Lower

37

19.3

Middle

148

77.1

Upper

6

3.1

Sex

Ethnicity

Socioeconomic

Reliability Analysis

In order to determine if the scales were functioning properly in the analysis, a

reliability analysis was performed on all scales used. The Almost Perfect Scale-Revised

26

had a Cronbach’s coefficient alpha of .84 consistent with the normality of the inventory

producing a .85 coefficient alpha (Slaney et al., 2001). The reliability analysis for the

Levenson Psychopathy Scale yielded a Cronbach’s coefficient alpha of .71, which was

not the robust .82 coefficient produced by the literature (Levenson, 1995), but

nonetheless still provided a strong coefficient alpha. The means produced in this analysis

did not support previous norms for the inventory; the current reliability analysis produced

a much higher mean (M = 48.41) than the mean produced by the original inventory (M =

25.25). The current analysis produced a standard deviation (SD = 9.17) that varied more

greatly than the standard deviation (SD = 6.86) produced by the literature (Levenson,

1995). The reliability analysis for the Self-Esteem Rating Scale produced a Cronbach’s

coefficient alpha of .70, which was much lower than the reliability alpha of .97 produced

by the existing inventory, which was shown to have excellent internal consistency

(Nugent & Thomas, 1993). Actual norms were not reported in the original literature.

The PANAS scales had coefficient alphas of .81 for the positive affect scale and

.80 for the negative affect scale. Both of which are slightly lower, although still

consistent with the literature, which shows an internal consistency coefficient alpha of .88

for the positive affect scale and coefficient alpha of .87 for the negative affect scale

(Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988). The means and standard deviations that were

gathered by the current reliability analysis (See Table 2) proved consistent with the

norms for the scales in previous literature; positive affect (M = 35.0, SD = 6.4), negative

affect (M = 18.1, SD = 5.9). The standard deviation of our negative affect scale was

27

slightly higher than reported norms, also the kurtosis in the current reliability analysis

was higher than the normal distribution indicating less variability in response. The

Satisfaction with Life scale reported with an internal consistency that was slightly lower

than the reported norm of coefficient alpha, .88. There were no actual norms that were

reported with the original inventory.

When comparing the reliabilities for the Dutweiler internal locus of control index,

the current analysis yielded a much lower reliability than the published norm (Duttweiler,

1984). The alpha coefficient of .68 fell much lower than the published .84 coefficient

alpha. The internal consistency reported for the Relationship Scales Questionnaire had a

Cronbach’s coefficient alpha of .77. Previous studies by Bartholomew and Griffin (1994)

had very small sample sizes, which did not allow for the establishment of measurement

norms for this inventory. The current reliability analysis for the Narcissistic Personality

Inventory produced a strong Cronbach’s coefficient alpha of .83, which is the exact

coefficient lambda published by the original scale (Raskin & Hall, 1979). However, the

means and standard deviations of the current analysis (See Table 2) are higher than the

norms reported by the inventory (M = 15.55, SD = 6.66). The Mach-IV

Machiavellianism scale produced a norm split-half reliability of .79, which is much

higher than the current internal consistency reliability analysis, which produced a

coefficient alpha of .63. This statistic indicates the reliability of the current inventory

was moderate compared to the published normality of the scale. The Physical Selfefficacy scale had good internal consistency, with a coefficient alpha of .81, and a testretest of .80. Both of these scores are higher than the current reliability analysis, which

28

produced a Cronbach’s coefficient alpha of .70. The published scale reported reliabilities

with a sample of 950 undergraduate students, a sample size that was much greater than

the current analysis which had only 192 undergraduate students, a good indication of why

the current reliability analysis may have fallen short of the published norm. All other

demographic data and actual norms were not reported with the inventory. The complete

table for the descriptive statistics and reliabilities produced on the inventories used in

the current study can be found in Table 2.

29

Table 2

Descriptive Statistics for the Inventories

Measure

Kurtosis Cronbach’s

Alpha

N

M

SD

Skew.

Self-Efficacy

192

82.87

12.27

.295

.087

.70

Panas Positive

192

37.33

6.05

-.351

-.237

.81

Panas Negative

192

21.80

7.21

.998

1.93

.80

Locus of Control

191

69.34

12.40

-.054

-.830

.68

Self-Esteem

192

211.14

31.52

-.506

-.316

.70

Satisfaction with Life

192

23.95

6.32

-.413

-.432

.83

Machiavellianism

191

72.90

7.70

.389

1.620

.63

Psychopathy

189

48.41

9.17

.129

-.290

.71

Narcissism

192

20.25

6.89

.413

-.223

.83

Relationship Scale

192

119.12

20.60

.445

.045

.67

Almost Perfect Scale

192

105.65

16.35

.222

.647

.84

Principal Components Analyses

An exploratory principle components analysis was computed on the criterion

variable of perfectionism. This analysis was done to see if there were three underlying

constructs assessing perfectionism as explained in the research literature, in order to

produce the criterion variable used in this study (i.e., adaptive and maladaptive

30

perfectionism). The sole purpose for this particular analysis was to produce the specific

criterion variables for this study. The 23-question items were analyzed using a principal

components analysis, even though the sample size was relatively small (N = 192). A

promax rotation was used to rotate the components in this analysis as it has proven to be

an efficient method and conceptually the best choice for the data.

Discrepancy was not significantly correlated with either High Standards, r(190) =

.18 or Order, r(190) = -.17, but the High Standards and Order were moderately

correlated, r(190) = .44. The structure coefficients produced in this analysis matched up

almost perfectly with what is reported in the literature and is presented in Table 3. The

first twelve items on the scale measure items associated with unhealthy, unattainable

lofty goals, where no level of achievement is ever satisfactory. This component was

named Discrepancy by the inventory developers and seems to best describe the unhealthy

behaviors of the perfectionist. The next seven items on the scale measure items

associated with set High Standards and goals that are intended to elicit their best efforts.

This component was named high standards to summarize those characteristics. The final

four items on the scale measure items were found to be associated with positive aspects

of perfectionism that describe neatness and orderliness. This component was named

Order by the inventory developers to describe those perfectionism mannerisms.

31

Table 3

Structure Coefficients for the Almost Perfect Scale-Revised Items

Item Content

Component

Discrepancy High Standards

Order

Can’t meet goals

.54

-.09

-.05

Not good enough

.80

-.17

-.08

Doesn’t meet high standards

.71

-.24

-.17

Best is not enough

.78

-.18

-.09

Unsatisfactory accomplishments

.68

-.14

-.20

Failed expectations

.83

-.06

-.12

Poor performance

.83

-.13

-.16

Unsatisfactory performance

.80

-.11

-.12

High standards not met

.75

-.16

-.13

Not good enough

.85

-.17

-.24

Failed performance

.78

-.17

-.15

Could have done better

.74

-.06

-.04

High standards at work

-.17

.73

.23

Expect great performance at work

-.01

.57

.24

High expectation of myself

-.18

.87

.32

High standards for myself

-.14

.87

.31

Expect the best of myself

-.15

.87

.44

Be the best at what I do

-.17

.82

.44

Strive for excellence

-.16

.84

.52

Orderly person

-.15

.45

.72

Neatness

-.17

.39

.91

Orderliness of belongings

-.12

.33

.91

Organization and Discipline

-.16

.41

.91

32

The three independent components produced by the measure were Discrepancy,

High Standards, and Order. As the research literature has suggested, given the

correlations of the subscales, there is sufficient information to believe the three subscales

are essentially measuring two dimensions, Adaptive and Maladaptive

Perfectionism. The Discrepancy subscale assesses Maladaptive Perfectionism, while the

High Standards and Order sub-scales assess Adaptive Perfectionism.

A reliability analysis on the Discrepancy subscale produced a very strong

Cronbach’s coefficient alpha of .91 consistent with the literature, which produced a

Cronbach’s coefficient alpha of .92 for the Discrepancy subscale (Slaney et al., 2001). A

reliability analysis on the High Standards subscale produced a strong Cronbach’s

coefficient alpha of .89 slightly stronger than the literature (Slaney et al., 2001) which

produced a strong coefficient alpha of .85. The reliability analysis on the Order subscale

also produced a Cronbach’s coefficient alpha of .89 which was extremely similar to the

literature’s (Slaney et al., 2001) coefficient alpha of .86 for the Order subscale. The High

Standards and Order subscales were combined into a single dimension of perfectionism,

Adaptive, per the literature’s implication (Slaney et al., 2001). Summing the ratings for

each item on the High Standards, and Order subscales formed the construct of Adaptive

perfectionism.

An exploratory principle components analysis was computed on the predictor

variable of adult attachment. This analysis was done to see if there were two underlying

constructs of adult attachment as explained in the research literature, in order to produce

33

the predictor variable used in this study (i.e. anxious and avoidant adult attachment). The

sole purpose for this particular analysis was to produce the specific predictor variables for

this study. The other predictor variables in this study were not multidimensional

constructs as reported in the literature.

Based on instructions by Griffin and Bartholomew (1994), 18 of the 30 self-report

items in their scale were included in a principle components analysis even though the

sample size was relatively small (N = 192). A promax rotation was used to rotate the

components and four subscales were produced as originally conceived: Secure,

Dismissing, Preoccupied, and Fearful. The structure coefficients produced for the fourcategory components of adult attachment are presented in Table 4. Consistent

with the literature (Griffin & Bartholomew, 1994), the correlations between the subscales

were relatively low. The Secure subscale was not significantly correlated with subscales

representing Fearful, r(190) = -.51, Preoccupied, r(190) = .09, or Dismissing, r(190) = .15. The Fearful subscale was not significantly correlated with subscales representing

Preoccupied, r(190) = -.19, or Dismissing, r(190) = .15. Finally, the Preoccupied

subscale was not significantly correlated with the Dismissing subscale, r(190) = -.40.

34

Table 4

Structure Coefficients for the Subscales of the Relationship Scales Questionnaire

Item Content

Component

Secure Preoccupied Fearful

Dismissing

Easily close to others

.85

.42

-.24

-.07

Worry about being alone

.72

.28

-.42

.34

Can depend on others

.72

.17

-.18

.21

Has others depend on me

.71

.31

-.29

-.17

Others may not accept me

.63

.24

-.36

.17

Comfortable without close relationships

.34

.61

.24

-.02

Want emotional intimacy

.22

.54

.15

-.25

Worry others wont value me as I do them

.18

.57

.18

-.31

Others are reluctant to get close

.16

.52

.17

-.03

Difficult to depend on others

.28

.23

.60

.25

Worry I will be hurt by others

-.44

.09

.71

.39

Difficult to trust others

-.23

.12

.66

.26

Uncomfortable close to others

-.56

-.04

.70

.17

Need to feel Independent

-.02

-.15

.24

.54

Need a close relationship

-.25

-.36

.19

.61

Need to feel self-sufficient

-.09

-.34

.05

.59

Don’t like being dependent on

-.12

-.31

.14

.54

Don’t like to depend on others

-.31

-.03

.36

.56

The four subscales computed are direct reflections of what was produced in the

literature (Griffin & Bartholomew, 1994). A reliability analysis was performed on these

four subscales and there were reported Cronbach’s coefficient alpha of .75 for the

35

Secure subscale, .72 for the Fearful subscale, .67 for the Preoccupied subscale, .70 for

the Dismissing subscale. There were no reliability statistics reported in the literature for

comparison for these four subscales.

The research literature suggested there were two underlying dimensions of adult

attachment as proposed by Griffin and Bartholomew (1994). The self-report scale

essentially revealed two dimensions; model of self (anxiety) and model of other

(avoidance). These two dimensions were computed using the instructions and following

equations from Griffin and Bartholomew (1994). The model of self (anxiety), was

derived by summing the individuals’ scores on the Secure and Dismissing subscales and

subtracting the individuals’ scores on the Preoccupied and Fearful subscales. The model

of other (avoidance) was derived by summing the individuals’ scores on the Secure and

Preoccupied subscales and subtracting the individuals’ scores on the Dismissing and

Fearful subscales.

Multiple Regression

Four exploratory standard multiple regression analyses were performed using the

criterion variables of Maladaptive Perfectionism (Discrepancy subscale), High Standards

subscale of perfectionism, Order subscale of perfectionism, and Adaptive Perfectionism

(computed using the High Standards subscale and the Order subscale).

The first exploratory standard multiple regression performed used the criterion

variable of Maladaptive Perfectionism (Discrepancy subscale) and locus of control, life

satisfaction, self-efficacy, self-esteem, negative affect, positive affect, Machiavellianism,

36

Psychopathy, Narcissism, and adult attachment style as the independent variables. The

assumption of multicollinearity was met with all VIF values reporting less than 10 and all

Tolerance values reporting greater than .01. As such, there is not a high intercorrelation

between the predictor variables used in the analysis. The model also satisfied the

assumption of linearity, normality, and homogeneity of variance. Please refer to Table 5

for the results of this standard regression model.

37

Table 5

Standard Regression Results for Predicting Scores of Maladaptive Perfectionism

Model

b

SE-b

Constant

4.36

1.617

Self-Efficacy

.010

Positive Affect

2

Structure

Coefficient

Beta

Pearson

r

sr

.008

.094

-.303

.005

-.480

-.022

.016

-.106

-.415

.006

-.657

Negative Affect*

.035

.013

.200

.429

.026

.679

Locus of Control

-.001

.009

-.008

-.402

.000

-.637

Self-Esteem*

-.013

.004

-.314

-.551

.033

-.873

Satisfaction with Life

-.025

.015

-.124

-.416

.008

-.659

Machiavellianism*

.023

.011

.141

.297

.014

.470

Narcissism

-.005

.005

-.080

-.273

.003

-.433

Psychopathy

.006

.010

.044

.234

.001

.370

Anxious Attachment

.010

.012

.052

-.064

.002

-.101

Avoidance Attachment

.009

.007

.081

-.020

.005

-.030

Note. N = 186. The dependent variable was Maladaptive Perfectionism. R2 = .398, Adjusted

R2 = .360. sr2 is the squared semi-partial correlation.

*p < .05

The model indicates that there is a significant relationship that exists between the

weighted linear composite of the independent variables as specified by the model and the

criterion variable of maladaptive perfectionism, F(11, 175) = 10.50, p < .001, adjusted

R2= .360. According to the Maladaptive Perfectionism model for prediction, individuals

38

who have lower attributes of self-esteem and higher attributes of Machiavellianism and

negative affect, are more likely to be maladaptive perfectionists. Adult attachment style

(anxious and avoidance) did not significantly predict Maladaptive Perfectionism. Based

on the structure coefficients, the underlying dimension appears to represent a negatively

oriented antisocial interaction pattern.

The second exploratory standard multiple regression performed used the criterion

variable of High Standards and locus of control, life satisfaction, self-efficacy, selfesteem, negative affect, positive affect, Machiavellianism, Psychopathy, Narcissism, and

adult attachment style as the independent variables. The assumption of multicollinearity

was met with all VIF values reporting less than 10 and all Tolerance values reporting

greater than .01. Therefore, there is not a high intercorrelation between the predictor

variables used in the analysis. The model satisfies the assumption of linearity, normality,

and homogeneity of variance. Please refer to Table 6 for standard regression results.

39

Table 6

Standard Regression Results for Predicting Scores on the High Standards Subscale of

Perfectionism

Beta

Pearson r

sr2

Structure

Coefficient

.006

-.089

.182

.004

.337

.044

.011

.315

.440

.060

.815

Negative Affect

.006

.009

.048

-.120

.001

-.222

Locus of Control*

.012

.006

.185

.365

.015

.676

Self-Esteem

-.002

.003

-.082

.321

.002

.594

Satisfaction with Life

.008

.011

.058

.252

.001

.466

Machiavellianism

.006

.008

.059

-.132

.002

-.244

Narcissism*

.008

.003

.190

.259

.022

.480

Psychopathy*

-.024

.007

-.267

-.289

.044

-.535

Anxious Attachment

.002

.009

.019

.077

.003

.143

Avoidance Attachment

-.002

.005

-.027

.032

.000

.060

Model

b

SE-b

Constant

5.978

1.149

Self-Efficacy

-.006

Positive Affect*

Note. N = 186. The dependent variable was High Standards Subscale of Perfectionism. R2 = .292,

Adjusted R2 = .247. sr2 is the squared semi-partial correlation.

*p < .05

The model indicates that there is a significant relationship that exists between the

weighted linear composite of the independent variables as specified by the model and the

40

criterion variable of High Standards subscale of perfectionism, F(11, 175) = 6.55, p <

.001, Adjusted R2= .247. According to the High Standards subscale of Perfectionism

model for prediction, individuals who have lower attributes of psychopathy, and higher

attributes of positive affect, locus of control, and narcissism are more likely to exhibit

characteristics of high standards perfectionism. Adult attachment style (anxious and

avoidance) did not significantly predict High Standards perfectionism. Based on the

structure coefficients, the predictive variate can be interpreted as representing positively

oriented emotional competency.

The third exploratory standard multiple regression performed uses the criterion

variable of Order with locus of control, life satisfaction, self-efficacy, self-esteem,

negative affect, positive affect, Machiavellianism, psychopathy, narcissism, and adult

attachment style as the independent variables. The assumption of multicollinearity has

been met with all VIF values reporting as less than 10 and all Tolerance values reporting

as greater than .01. Therefore, there is not a high intercorrelation between the predictor

variables used in the analysis. The model satisfies the assumption of linearity, normality,

and homogeneity of variance. Please refer to Table 7 for the results of this standard

regression model.

41

Table 7

Standard Regression Results for Predicting Scores on the Order Subscale of

Perfectionism

Beta

Pearson r

sr2

Structure

Coefficient

.009

.024

.156

.000

.389

.068

.018

.331

.345

.066

.860

Negative Affect

-.005

.015

-.032

-.136

.000

-.339

Locus of Control

.016

.010

.159

.265

.011

.661

Self-Esteem

-.003

.005

-.084

.208

.002

.518

Satisfaction with Life

-.012

.018

-.060

.148

.002

.369

Machiavellianism

-.011

.013

-.066

-.169

.003

-.421

Narcissism

-.033

.006

-.047

.078

.001

.194

Psychopathy

-.010

.012

-.074

-.190

.003

-.473

Anxious Attachment

.000

.014

.000

.026

.000

.064

Avoidance Attachment

-.007

.008

-.062

-.022

.003

-.055

Model

b

SE-b

Constant

6.483

1.869

Self-Efficacy

.002

Positive Affect*

Note. N = 186. The dependent variable was Order Subscale of Perfectionism. R2 = .161, Adjusted

R2 = .108. sr2 is the squared semi-partial correlation.

*p < .05

The model indicates that there is a significant relationship that exists between the

weighted linear composite of the independent variables as specified by the model and the

42

criterion variable of the Order subscale of perfectionism, F(11, 175) = 3.05, p < .001,

adjusted R2= .108. According to the Order Subscale of Perfectionism model for

prediction, individuals who have higher attributes of positive affect are more likely to

exhibit characteristics of Order perfectionism. Adult attachment style (anxious and

avoidance) did not significantly predict Order perfectionism. Based on the structure

coefficients, the predictive variate can be interpreted as representing positively oriented

self-confidence.

The fourth exploratory standard multiple regression performed uses the criterion

variable of Adaptive Perfectionism which are the High Standards and Order subscales

combined, with locus of control, life satisfaction, self-efficacy, self-esteem, negative

affect, positive affect, Machiavellianism, psychopathy, narcissism, and adult attachment

style as the independent variables. The High Standards and Order subscales were

combined into a single dimension of perfectionism, Adaptive, per the literature’s

implication (Slaney et al., 2001). The assumption of multicollinearity has been met with

all VIF values reporting as less than 10 and all Tolerance values reporting greater than

.01. Therefore, there is not a high intercorrelation between the predictor variables used in

the analysis. The model satisfies the assumption of linearity, normality, and homogeneity

of variance. Please refer to Table 8 for the results of this standard regression model.

43

Table 8

Standard Regression Results Predicting Scores for Adaptive Perfectionism

Model

b

SE-b

Constant

6.161

1.145

Self-Efficacy

-.003

Positive Affect*

2

Structure

Coefficient

Beta

Pearson r

sr

.006

-.043

.201

.001

.370

.053

.011

.381

.468

.087

.862

Negative Affect

.002

.009

.014

-.151

.000

-.278

Locus of Control*

.014

.006

.204

.377

.019

.694

Self-Esteem

-.003

.003

-.098

.317

.003

.584

Satisfaction with Life

.001

.011

.004

.241

.000

.444

Machiavellianism

.000

.008

.002

-.176

.000

-.324

Narcissism

.004

.003

.095

.207

.005

.381

Psychopathy*

-.019

.007

-.211

-.287

.027

-.530

Anxious Attachment

.001

.009

.011

.063

.000

.116

Avoidance Attachment

-.004

.005

-.050

.008

.002

.015

Note. N = 186. The dependent variable was Adaptive Perfectionism. R2 = .295, Adjusted R2 =

.250. sr2 is the squared semi-partial correlation.

*p < .05

The model indicates that there is a significant relationship between the weighted

linear composite of the independent variables as specified by the model and the criterion

variable of Adaptive Perfectionism, F(11, 175) = 6.647, p < .001, adjusted R2= .250.

According to the Adaptive Perfectionism model for prediction, individuals who

44

have higher attributes of positive affect, and locus of control, and lower attributes of

psychopathy are more likely to exhibit characteristics of adaptive perfectionism. Adult

attachment style (anxious and avoidance) did not significantly predict Adaptive

Perfectionism. Based on the structure coefficients, the predictive variate can be

interpreted as representing social well-being.

45

Chapter 4

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to investigate the role of anxiety and avoidance

dimensions of adult attachment and the “Dark Triad” personality traits in conjunction

with various other personality traits (i.e., self-efficacy, self-esteem, positive affect,

negative affect, locus of control, satisfaction with life) in adaptive and maladaptive

dimensions of perfectionism. Past research on perfectionism has focused on other

personality traits, mainly the Big Five personality factors (extraversion, neuroticism,

agreeableness, conscientiousness, openness to experience). The present research sought

to examine an alternative model of perfectionism using several types of personality

characteristics together with adult attachment dimensions.

The results of this study showed four regression components that were descriptive

of specific dimensions of perfectionism (i.e., Maladaptive and Adaptive perfectionism

and the High Standards and Order subscales) delineated by Hamachek (1978). This

approach supports Slaney’s et al. (2001) perspective that the independence of the

Discrepancy subscale (maladaptive) from the High Standards and Order subscales are

well suited to measure the separate positive and negative aspects of perfectionism. This

is relevant to past research that suggests that there is a significant distinction between

adaptive and maladaptive perfectionism based on how perfectionists use their

perfectionism (Ashby & Kottman, 1996; Kottman & Ashby, 1999). Furthermore, from

an Adlerian perspective, the adaptive perfectionist, who experiences less distress related

46

to perfectionism and is striving for high standards, may be appropriately pursuing

superiority (Flett & Hewitt, 2002, p. 83). In contrast, the maladaptive perfectionist may

pursue high standards to avoid feelings of inferiority. This avoidance may be manifested

in the need to out-perform other individuals and may be directly related to a family

dynamic where love and acceptance are based on performance (Flett & Hewit, 2002, p.

83).

Previous research by Hamachek (1978) suggests that the “maladaptive”

perfectionists rarely feel satisfied, if ever, and strongly critique themselves on all tasks.

The maladaptive perfectionists are typically described as having excessive concerns

about making mistakes, excessive perceptions of self-doubt, and excess perceptions of

failure in order to achieve personal standards (Frost et al., 1993). The regression results

suggest that individuals who have lower attributes of self-esteem and higher attributes of

Machiavellianism and negative affect, are more likely to be maladaptive perfectionists.

Hamachek (1978) also suggested that “adaptive” perfectionists reported feeling satisfied