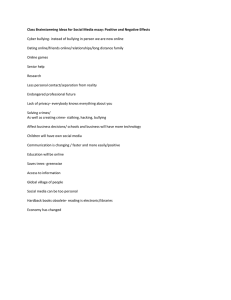

A DESCRIPTIVE STUDY ON THE PERSPECTIVES OF PARENTS AND

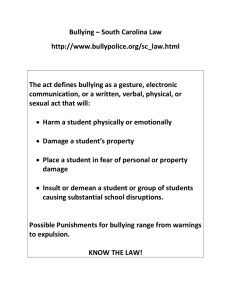

advertisement