RETURNING FROM THE SUCK DIAGNOSED WITH PTSD AND SUBSTANCE ABUSE

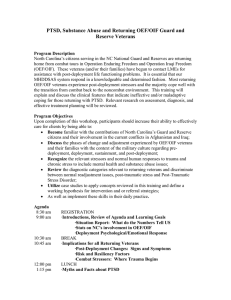

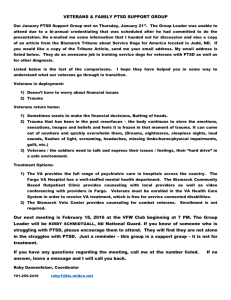

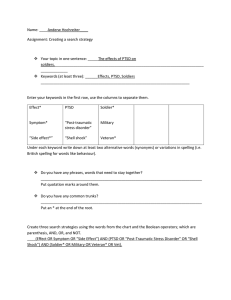

advertisement