PART 1 ITEM NO. (OPEN TO THE PUBLIC)

advertisement

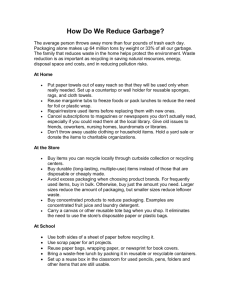

PART 1 ITEM NO. (OPEN TO THE PUBLIC) _____________________________________________________________ REPORT OF THE LEAD MEMBER FOR ENVIRONMENTAL SERVICES _____________________________________________________________ TO THE ENVIRONMENTAL SCRUTINY COMMITTEE ON 17TH DECEMBER 2001 _____________________________________________________________ CONTACT OFFICER: Wayne Priestley TEL NO: 793 2060 _____________________________________________________________ TITLE: EUROPEAN AND UK INITIATIVES TO REDUCE AND RECYCLE PACKAGING WASTE _____________________________________________________________ RECOMMENDATIONS: That members note the report That members consider writing to the Secretary of State for the Environment regarding the feasibility of an hypothecated litter tax. _____________________________________________________________ EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: The report details how the UK and other European countries are addressing the issue of reducing the amount of packaging waste being produced. Emphasis is placed on the Green Dot scheme in Germany and the UK’s Packaging Waste Directive. In addition to the recycling of packaging waste, the report also considers the possibility of a hypothecated litter tax on packaging, which regularly appears as street litter. _____________________________________________________________ BACKGROUND DOCUMENTS: (available for public inspection) European Goes Green Dot – Duales System Deutschland AG (2001) Annual Report 2000 Der Grüne Punkt – Duales System Deutschland AG Waste Strategy 2000 for England and Wales - DETR 1.0 BACKGROUND 1.1 Environmental Scrutiny Committee requested that a report be prepared on how other European countries were dealing with the issue of recycling or reducing the amount of packaging waste, which often contributes to the problem of street litter. 1.2 Information was promised to the committee on ‘Der Grüne Punkt’ or ‘The Green Dot System’ now operating in over 13 European Countries, which has had a high degree of success in reducing the amount of waste packaging being produced. WARD(S) TO WHICH REPORT RELATE(S) N/A ___________________________________________________________ KEY COUNCIL POLICIES Environmental Strategy Recycling Policies Waste Management _____________________________________________________________ 2.0 DETAILS 2.1 At the end of the 1980’s the Federal Republic of Germany was facing a serious crisis regarding the growing amount of waste it was producing and the simultaneous lack of landfill capacity. In 1990, packaging accounted for c. 30% by weight and 50% by volume of all household waste. As a result in 1991 the Packaging Ordinance was passed. This law’s aim was to prevent or reduce packaging waste. If this were not possible, then such waste must either be re-used or recycled to ensure materials were kept in the production loop as long as possible. 2.2 The main point of the Packaging Ordinance was that industry was forced to accept responsibility for its products, in that it obliged manufacturers, fillers and distributors of transport, secondary and sales packaging to take back and recycle their used packaging. At the same time the Ordinance also gave producers and retailers the chance to transfer these obligations to private sector organisations to carry out the work on their behalf so long as targets and responsibilities were met. 2.3 In response to these new requirements a dual system for the collection of packaging waste was established by the private sector. This operates by issuing collection contracts to waste collection companies, who collect packaging waste from those obligated, on the understanding that the obligated companies paid a licence fee to place a ‘Green Dot’ on their packaging to signify they were funding work which led to their packaging being recycled. In this way the Green Dot was, and still is, seen as a symbol of economic action involving ecological responsibility and as such, can significantly boost the image of the company. 2.4 To date over 19,000 companies have signed up to the Green Dot scheme in Germany alone. In addition 13 other European and nonEuropean counties have also adopted the scheme with the result that over 460 billion pieces of packaging marked with the Green Dot are distributed worldwide. 2.5 Since the licence fees that have to be paid for the use of the Green Dot are based on the type of packaging material, the weight and number of items made, the Green Dot has given companies a great incentive to optimise packaging. In order to lower their costs, companies are increasingly cutting down on packaging material, changing the material composition and using more environmentally friendly and recyclable substances. Some examples are the total elimination of cardboard boxes as secondary packaging and the reduction of the weight of cans and glass containers. This has already made a tremendous contribution towards the conservation of natural resources. 2.6 Reducing the amount of packaging used, has always been at the very core of the dual system, which depends on the kerbside collections and bring systems to collect its materials. For the view is that, recycling is not enough in itself to stop the growing waste problem, waste reduction is the ultimate aim. 2.7 The company, which organises this whole system, is a non-profit making body known as Duales System Deutschland AG and it is responsible for administering the waste collection contracts and the issuing of licences to obligated companies. It also has a major role in funding the ongoing development of sorting and processing technologies for packaging recycling with the objective of reducing costs of packaging but improving eco-efficiency. As a privately owned institution it is trying to achieve a fair conciliation of interests in respect of the demands of the environmental policy, the fee-paying industry, the local authorities and the waste management and recycling firms. Its goal is to make state interventions such as take-back and deposit obligations unnecessary and to eliminate them for the benefit of the fee-payer. 2.8 The success of the Green Dot scheme is that over 80% of all waste packaging produced is subject to recycling, and with regards to waste minimisation the amount of waste packaging produced, this has fallen by 4% which although small, has to be measured against the fact had action not been taken, waste packaging was expected to have risen in amount by a further 20% by the present date. The avoidance effect in Germany as a result of the Packaging Ordinance and the Green Dot initiative is therefore probably up to 25% in real terms. 3.0 EUROPEAN LEGISLATION 3.1 Current EU minimum recycling rates for packaging waste need to be doubled to achieve an optimum balance between economic costs and environmental benefits, according to recent European Commission thinking. The view is that current recycling targets for household and industrial packaging should be increased form 25% and 45% currently, to 50% and 68% by 2006. 3.2 To achieve these targets the following recycling rates would need to be achieved for each material. 28 – 38% for plastics 60 – 70% for steel 25 – 31% for aluminium 47 – 65% for word 60 – 74% for paper and board 53 – 87% for glass It is also proposed that separate collection systems would be needed rather than trying to extract these materials from unsorted waste. 3.3 With regards to current packaging recycling rates in EU member states, all but three have met the minimum 50% recovery target, these being Spain, Italy and the UK. 4.0 THE UK’S RESPONSE 4.1 The UK in response to the EU Directive on Packaging and Packaging Waste, aims to achieve the recycling of 50% of the 8 million tonnes of packaging waste produced in the UK. It is estimated that the cost of this, is likely to be 2p per £10 of every shopping bill. These targets are part of the Packaging Waste Regulations, which came into force on the 6th March 1997. 4.2 In the UK, businesses are only affected if they fall into any three of the following categories. They are involved in: Manufacturing raw materials used for packaging Converting raw materials into packaging Packing or filling packaging Selling packaging or packaged products to the final user or consumer They won and handle more than 50 tonnes of packaging materials or packaging each year. They have an annual turnover of more than £2 million. 4.3 Each stage of the process will be responsible for a percentage of the turnover. Raw material manufacturers 6% Converters 9% Packers/fillers 37% Sellers 48% However each business is only responsible for the packaging waste passed on the next company/person in the supply chain, e.g. a distributor or wholesaler would be responsible for the cardboard boxes delivered to the retailer, and the retailer would be responsible for the shrink wrapping and paper or plastic carrier bag passed on the consumer. 4.4 The monitoring of compliance with the regulations is achieved by businesses being subject to registering and providing data as an individual company, or through an approved compliance scheme, which issues Packaging Recovery Notes, known as PRN’s. Each business registering has to pay an annual registration fee of £950. 4.5 As with the Green Dot system in Germany and other European countries, private sector organisations have established themselves to provide collection schemes e.g. Valpak Ltd. Such organisations offer assistance by helping businesses to understand the legislation, calculate the amounts of packaging needing recycling, how to register, establish regional and local forums for businesses to discuss recycling etc. 4.6 One weakness of the scheme is that companies do not necessarily need to recycle to comply with the regulations, but can simply buy PRN’s from reprocessors. This is achievable by the fact some companies who are ecologically-minded recycle more than they need to, therefore this surplus still attracts PRN’s which are available to be bought by non-recyclers which allows them to show they are complying with their requirements. 4.7 However, as targets for recycling of packaging waste are increased, the amount of surplus reduces and therefore there are fewer PRN’s available to non-recyclers. This lack of PRN’s forces their value up and as such it becomes expensive to keep buying PRN’s rather than recycling your waste, for which PRN’s can be bought more cheaply as well as gaining income from the materials your company has recycled. Further to this there will come a time when targets are increased to such a level where no PRN’s are available to non-recyclers, and as such the non-recycler will be unable to prove they are meeting requirements and therefore legal action can be taken against them by the Environment Agency (although this scenario is still a long way off). 4.8 Although seemingly flawed, the income from the sale of PRN’s, which is made by the reprocessor who accepts materials for recycling, has to be reinvested into recycling systems, thereby providing greater capacity to accept materials for recycling. In addition money raised from the sale of compliance licences via organisations such a Valpak, is also used to invest in new packaging technology to reduce or even phase out certain types of packaging. 4.9 The UK has met its own expectations for the recycling of, and recovery of packaging waste, and already with 27% recycling, meets the EU Directive 25% target for minimum recycling. The material-specific targets for each material (15% minimum in 2001) have also been met with the exception of aluminium (13%) and plastic (8%). However as highlighted at 3.1 and 3.2, targets are expected to be increased in the coming years and this will mean significant improvements will need to be made if new EU targets are to be met. Failure to meet such targets will result on financial penalties being imposed on the UK Government. 4.10 A critical point not raised in this report so far, is that packaging targets are not the sole responsibility of businesses, as around a half of all packaging waste placed on the market ends up in the household waste stream, particularly glass and aluminium. The collection of packaging waste is therefore as much a responsibility of local authorities as it is businesses. Recycling of such waste can only be achieved via the introduction of kerbside collections and bring sites. Therefore there is a need to develop a strong infrastructure of collection systems is recycling targets are to be met, and in addition there will need to be the development of sufficient markets for recycled materials. Table 1 Estimated proportion of packaging materials arising in the household and commercial/industrial waste streams MATERIAL HOUSEHOLD COMMERCIAL/INDUSTRIAL WASTE STREAM WASTE STREAM Aluminium 96% 4% Steel 78% 22% Plastic 71% 29% Glass 84% 16% Paper 13% 87% 5.0 IMPACT ON STREET LITTER 5.1 Initiatives on reducing packaging waste could have a significant effect on some forms of street litter, most notably plastic wrappings, beverage cans and paper. The desire to reduce secondary packaging could mean many of the outer-casings on certain types of products may be phased-put e.g. non-essential wrappers around foods and drinks. However, litter will still continue to be found on the City’s streets in some form or other, until the long-term educational drive to stop littering bares fruit. 5.2 What perhaps needs to be considered is a similar scheme to the Landfill Tax where a litter tax can be introduced on those products, which produce the most evident street litter, such as fast foods, cigarettes, chewing gum etc. This tax could be hypothecated as is the Landfill Tax, to research better ways to produce goods that do not need disposable elements, fund high profile litter campaigns, develop better street cleansing technologies (especially in relation to chewing gum removal) and finance studies into best practice elsewhere. 5.3 Which products to tax, could simply be identified by using existing data from national litter surveys, or by carrying out a new nationwide survey funded in advance, from monies raised by the new tax. Obviously such a tax could be unpopular, as are all taxes, but it would probably be one most welcomed by local authorities and the public alike. 6.0 CONCLUSION 6.1 This report has intended to show how pan-European attempts are being made to reduce the amount of waste packaging in circulation. These attempts affect all sectors of society from large scale packaging manufacturers and users, to every home across Europe. Significant strides are being made by the business sector but a major role must be made by the consumer, either through recycling, refusing to buy, or returning unnecessary packaging. 6.2 In relation to litter, although reducing the amount of packaging waste will help to reduce the ability to drop litter, litter still needs to be attacked both through product design, education and enforcement. 6.3 It is hoped that the contents of this report have given some hope for the future with regards to creating a more sustainable and cleaner environment in which we must all live and work. G:\Committee Reports\ES Scrutiny Committee\17-12-01.doc