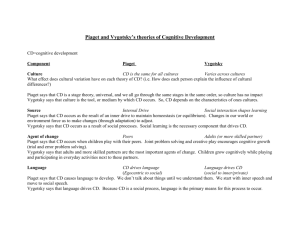

1 Meccaci notes that this whole chapter represents expository material concerning... ’s students Josefina Shif, who ...

advertisement