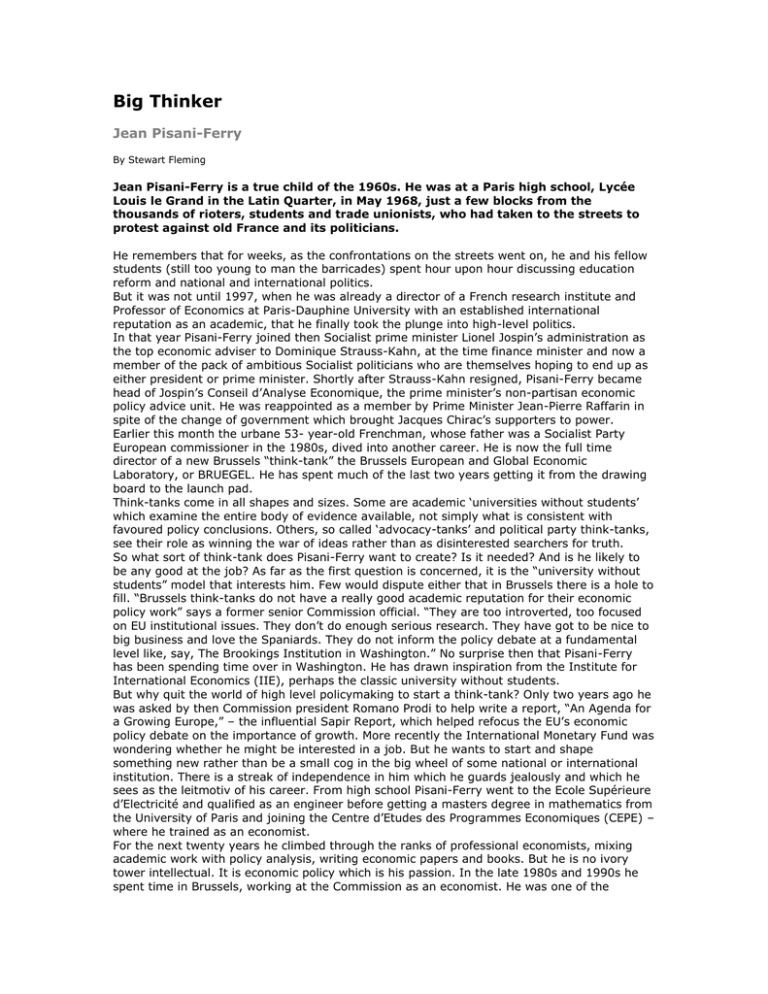

Big Thinker

Jean Pisani-Ferry

By Stewart Fleming

Jean Pisani-Ferry is a true child of the 1960s. He was at a Paris high school, Lycée

Louis le Grand in the Latin Quarter, in May 1968, just a few blocks from the

thousands of rioters, students and trade unionists, who had taken to the streets to

protest against old France and its politicians.

He remembers that for weeks, as the confrontations on the streets went on, he and his fellow

students (still too young to man the barricades) spent hour upon hour discussing education

reform and national and international politics.

But it was not until 1997, when he was already a director of a French research institute and

Professor of Economics at Paris-Dauphine University with an established international

reputation as an academic, that he finally took the plunge into high-level politics.

In that year Pisani-Ferry joined then Socialist prime minister Lionel Jospin’s administration as

the top economic adviser to Dominique Strauss-Kahn, at the time finance minister and now a

member of the pack of ambitious Socialist politicians who are themselves hoping to end up as

either president or prime minister. Shortly after Strauss-Kahn resigned, Pisani-Ferry became

head of Jospin’s Conseil d’Analyse Economique, the prime minister’s non-partisan economic

policy advice unit. He was reappointed as a member by Prime Minister Jean-Pierre Raffarin in

spite of the change of government which brought Jacques Chirac’s supporters to power.

Earlier this month the urbane 53- year-old Frenchman, whose father was a Socialist Party

European commissioner in the 1980s, dived into another career. He is now the full time

director of a new Brussels “think-tank” the Brussels European and Global Economic

Laboratory, or BRUEGEL. He has spent much of the last two years getting it from the drawing

board to the launch pad.

Think-tanks come in all shapes and sizes. Some are academic ‘universities without students’

which examine the entire body of evidence available, not simply what is consistent with

favoured policy conclusions. Others, so called ‘advocacy-tanks’ and political party think-tanks,

see their role as winning the war of ideas rather than as disinterested searchers for truth.

So what sort of think-tank does Pisani-Ferry want to create? Is it needed? And is he likely to

be any good at the job? As far as the first question is concerned, it is the “university without

students” model that interests him. Few would dispute either that in Brussels there is a hole to

fill. “Brussels think-tanks do not have a really good academic reputation for their economic

policy work” says a former senior Commission official. “They are too introverted, too focused

on EU institutional issues. They don’t do enough serious research. They have got to be nice to

big business and love the Spaniards. They do not inform the policy debate at a fundamental

level like, say, The Brookings Institution in Washington.” No surprise then that Pisani-Ferry

has been spending time over in Washington. He has drawn inspiration from the Institute for

International Economics (IIE), perhaps the classic university without students.

But why quit the world of high level policymaking to start a think-tank? Only two years ago he

was asked by then Commission president Romano Prodi to help write a report, “An Agenda for

a Growing Europe,” – the influential Sapir Report, which helped refocus the EU’s economic

policy debate on the importance of growth. More recently the International Monetary Fund was

wondering whether he might be interested in a job. But he wants to start and shape

something new rather than be a small cog in the big wheel of some national or international

institution. There is a streak of independence in him which he guards jealously and which he

sees as the leitmotiv of his career. From high school Pisani-Ferry went to the Ecole Supérieure

d’Electricité and qualified as an engineer before getting a masters degree in mathematics from

the University of Paris and joining the Centre d’Etudes des Programmes Economiques (CEPE) –

where he trained as an economist.

For the next twenty years he climbed through the ranks of professional economists, mixing

academic work with policy analysis, writing economic papers and books. But he is no ivory

tower intellectual. It is economic policy which is his passion. In the late 1980s and 1990s he

spent time in Brussels, working at the Commission as an economist. He was one of the

authors – together with Centre for European Policy Studies director Daniel Gros and

Commission President José Manuel Barroso’s deputy head of cabinet Alexander Italianer – of

the ‘One Market, One Money’ report. A colleague remembers that he also produced an

excellent report on Russia. He became an adjunct professor at the Université Libre de

Bruxelles, and Professor at the Ecole Polytechnique in Paris.

The events of 1968 left their impression. Like his father who was a leftist minister in Charles

de Gaulle’s government in the 1960s before jumping ship to the Socialist Party, Pisani-Ferry’s

sympathies too have been consistently to the centre left.

But he did not want to tread directly in his father’s footsteps or make a career clinging to the

coattails of this or that politician. Hence the wait until 1997 before taking a top government

post. While his sympathies are to the left, he tries to make sure that they do not interfere with

his intellectual analysis – that streak of independence again.

In the late 1990s he courted controversy, particularly amongst fellow Socialists. He argued

that the job creating policy of the 35 hour week which Socialist minister of labour Martine

Aubry, the daughter of former commission president Jacques Delors, had sponsored, no longer

answered the nation’s needs. Drawing on the ‘Anglo-Saxon’ experience, despised in France, he

argued for the government to embrace the idea of an employment tax credit to encourage the

low paid to take jobs, and not, he insists, “workfare”.

Times had changed. France’s labour market was tightening. Ensuring the availability of

adequate labour was, he believed, one of the main long-term challenges facing France. The

Left dubbed him “a Milton Friedman follower”, evoking the reputation of one of America’s most

right-wing, and most distinguished economists. His reaction? “Tant Pis.” The analysis was

correct. It is the same with his political contacts. He retains his independence. Although his

first top government posting was working for Strauss-Kahn, he maintains good relations with

other key figures in the French Socialist Party, including François Hollande, not allowing

himself to become identified solely with the clique which owes its loyalty, and its hopes of

office, to Strauss-Kahn. “He [Pisani-Ferry] is a very serious economist and a very useful

person to have around because he has such great breadth of experience coupled with very,

very strong analytical skills,” says a former EU official who worked with him in the halcyon

days of Delors. “He is one of the most original and creative thinkers in France, not only on

economic policy but also on the future of Europe,” says Charles Grant, founder and director of

the Centre for European Reform in London.

Few doubt that BRUEGEL will succeed. Pisani-Ferry has used his reputation to persuade twelve

EU governments to take part, including France, Germany and even Britain (he is close to Ed

Balls, formerly Chancellor Gordon Brown’s top economic adviser). Eighteen multi-national

companies have also agreed to contribute to the think-tank’s H2 million a year budget. Mario

Monti, another formidable intellect, is on board as chairman. Pisani-Ferry is determined to

steer clear of the institutional navel-gazing which pre-occupies so much of Brussels and its

think-tanks. “The EU is a global player with global responsibilities. We will seek to bring a

European perspective to global issues and a global perspective to EU issues,” he says. Not a

bad mission statement.

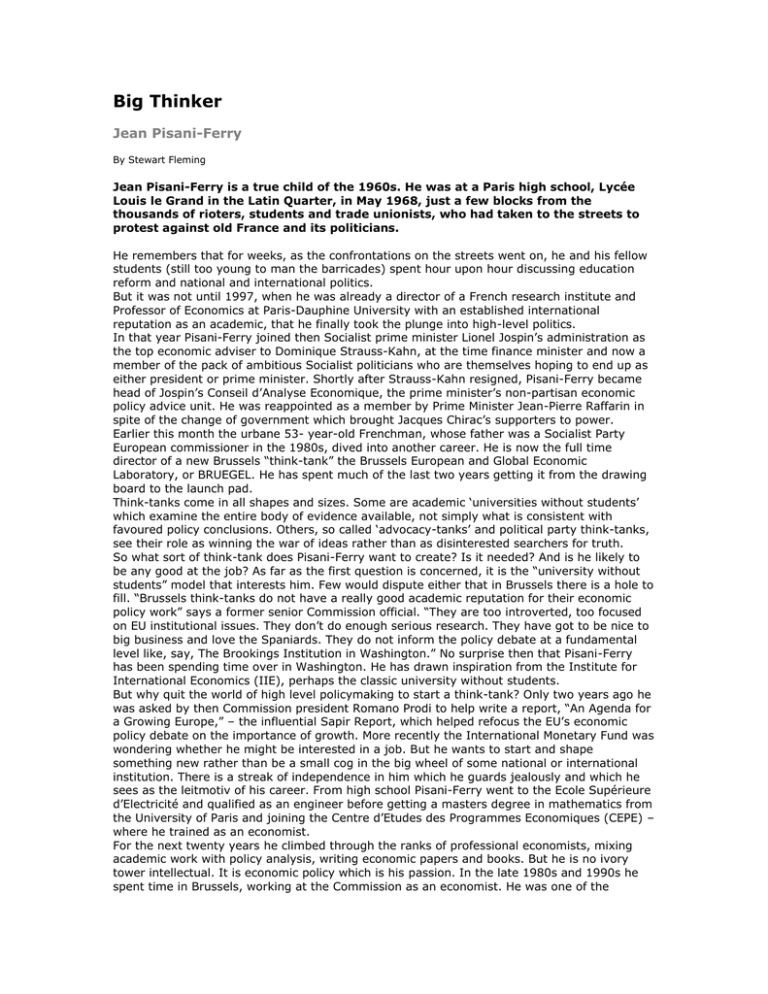

Biography

1951: Born Boulogne-Billancourt, France

1977: Graduates from centre d’etudes des programmes économiques, Paris

1992-97: Director of the Centre d'études prospective et d'information internationales

(CEPII)

2000-01: President of the French prime minister's Economic Advisory Council

2001:- Professor of economics at Université de Paris-Dauphine

2003: Co-author An Agenda for a Growing Europe, (the Sapir report)

2002-04: Senior adviser to the director of the French ministry of finance

2005:- Director, Brussels European and Global Economic Laboratory (BRUEGEL)

© Copyright 2005 The Economist Newspaper Limited. All rights reserved.