Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonia Trying to make sense of the letters February 2006

advertisement

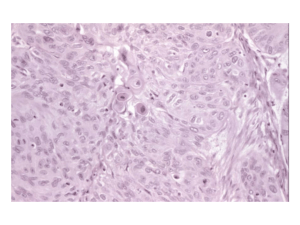

Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonia Trying to make sense of the letters Michelle Thompson, MS4 February 2006 Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias (IIP’s) Group of uncommon parenchymal lung diseases Similar pattern of lung injury to those seen in collagen vascular disease, drug reactions, asbestosis and chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis “Idiopathic” reserved for conditions in which the cause of lung injury pattern is unknown Classification “So diverse are the different forms and so varied the conditions under which this change occurs that a proper classification is extremely difficult” Osler speaking of IIP (1892) Classification A number of classification schemes, names and definitions have been associated with the IIP’s over the years leading to a great deal of confusion (and article titles referring to “alphabet soup”) American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society (ATS/ERS) met in 2002 to clarify nomenclature and describe the clinical, radiologic and histologic patterns of these conditions Participants included thoracic radiologists, pulmonologists and pulmonary pathologists Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias (clinical nomenclature as proposed by ATS/ERS) Include (in order of frequency): Usual Interstitial Pneumonia (UIP) Non-specific Interstitial Pneumonia (NSIP) Cryptogenic Organizing pneumonia (COP) Acute Interstitial Pneumonia (AIP) Respiratory Bronchiolitis-Associated Interstitial Lung Disease (RB-ILD) Desquamative Interstital Pneumonia (DIP) Lymphoid Interstitial Pneumonia (LIP) Diagnosis of IIP ATS/ERS guidelines emphasize the importance of combined clinical, radiologic and histologic diagnosis of IIP’s The MOST IMPORTANT distinction is between UIP and the other IIP’s due to prognostic and therapeutic implications Diagnosis of IIP HIGHLIGHTS: If HRCT gives confident diagnosis of UIP, no lung biopsy needed and diagnostic process is done If equivocal findings on HRCT, then surgical lung biopsy considered Figure from UpToDate, adapted from ATS/ERS guidelines Usual Interstitial Pneumonia (UIP) Also known as Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) Most common IIP Primarily a fibrotic condition Clinical Findings in UIP Age >50 Slight male predominance Symptoms usually present 6 months prior to presentation Progressive shortness of breath, non-productive cough Physical exam: end-inspiratory crackles at lung bases “velcro” lung Lung function tests: restrictive pattern Decreased DLCO Histologic Findings in UIP Histology: Fibroblastic foci at the edge of dense scars Subpleural, paraseptal and/or peribronchovascular distribution Dense fibrosis causes remodeling of lung architecture and frequent honeycomb fibrosis Two distinguishing characteristics from other IIP’s 1. Temporal heterogeneity: fibrotic lesions of different stages within same biopsy specimen 2. Spatial heterogeneity: patchy lung involvement Histology of UIP Left to right: 1. Patchy fibrosis, subpleural distribution. Some lymphoid aggregates (black arrow). Areas of normal lung also present. 2. Fibroblastic focus (white arrow) adjacent to dense collagenous scar. Figures from Lynch et al. 2005 Radiographic features of UIP Radiographs Bilateral and basilar irregular linear opacities (close to 100% of cases) Ground glass opacities Honeycombing Loss of lung volumes Normal radiograph in 2-8% of cases Early changes UIP: peripheral, irregular linear opacities and normal lung volumes Late features UIP: same patient 2 years later. Peripheral, irregular linear opacities and progressive loss of lung volume Images from McAdams et al., 1996 Late features UIP showing bilateral, coarse, reticular opacities with architectural distortion, volume loss and honeycombing Images from McAdams et al., 1996 CT features of UIP Reticular opacities with traction bronchiectasis Honeycombing (96% of cases) Ground glass opacity (less extensive than reticular pattern) Architectural distortion reflecting fibrosis Distribution: basal/peripheral and patchy CT features of UIP Left: left lower lobe shows peripheral ground-glass opacity and reticular patterns with traction bronchiectasis (arrow) Right: same patient two years later with progression of ground-glass to reticular pattern and honeycombing and progression of traction bronchiectasis Images from Lynch et al., 2005 Clinical Course in UIP Gradual deterioration, with possible periods of rapid decline Mean survival is 2.5-3.5 years from time of diagnosis As UIP is predominantly a fibrotic condition, does not typically respond to steroid treatment Non-specific Interstitial Pneumonia (NSIP) Second most frequently diagnosed IIP more favorable prognosis than IPF/UIP ATS/ERS guidelines stress that a finding of an NSIP pattern on biopsy should “prompt the clinician to redouble efforts to find potential causes” (collagen vascular disease, exposures) Clinical findings in NSIP Mean age of onset is 40-50 No sexual predominance No association with cigarette smoking Gradual onset, some patients may have subacute course The median duration of symptoms before diagnosis is 6-31 mo in different series Symptoms: progressive SOB, cough, fatigue Half present with history of weight loss Physical Exam: crackles at lung bases Lung function tests: restrictive pattern with decreased DLCO Histology of NSIP Because features are “non-specific”, histology is difficult to define Spatially homogenous alveolar wall thickening Temporal homogenous pattern Two main types: 1. Fibrotic: dense or loose interstitial fibrosis lacking temporal heterogeneity or patchy features 2. Cellular: Mild-moderate interstitial chronic inflammation Type II pneumocyte hyperplasia in areas of inflammation Fibrotic NSIP NSIP with fibrosing pattern. Alveolar walls (arrows) show thickening caused by fibrosis. No fibroblastic foci are present. Image from Lynch et al., 2005 Cellular NSIP Photomicrograph showing NSIP with cellular pattern. Alveolar walls (arrows) are infiltrated by a chronic inflammatory infiltrate. Image from Lynch et al., 2005 Fibrotic vs. Cellular NSIP Main importance is prognostic. Patients with predominant fibrosis have a poorer prognosis than those with cellular NSIP Figure below shows survival curves for patients with UIP, fibrotic NSIP (FNSIP) and Cellular NSIP (CNSIP). Those with CNSIP are shown to have the best survival. Figure from Lynch et al., 2005 Radiographic Features of NSIP Irregular linear opacities Air space consolidation Bilateral and basilar pattern Radiograph normal in 14% of cases Radiographic features of NSIP Basilar opacities and normal lung volumes Image from McAdams et al., 1996 CT features of NSIP Scattered ground glass opacities Basal predominance Consolidation uncommon and honeycombing rare Irregular linear opacities Fibrosis (lobar volume loss, reticular pattern, and/or traction bronchiectasis) CT features of NSIP Top: Fibrotic NSIP. Ground glass opacity with traction bronchiectasis (arrows) Arrowhead indicating posterior displacement of left major fissure denoting volume loss Bottom: Cellular NSIP. Ground glass opacity with reticular pattern. Images from Lynch et al., 2005 Clinical Course of NSIP Significantly better prognosis than UIP Evidence for corticosteroid efficacy is from retrospective reviews of observational studies. (2530% of patients improved)* Relapse may occur *Collard et al., 2003 Cryptogenic Organizing Pneumonia (COP) (IIP formerly known as BOOP) Third most common IIP Although process is primarily intraalveolar, it is included with IIP’s because of its idiopathic nature and because its appearance may overlap with other IIP’s Organizing Pneumonia: (COP or BOOP) Histology: Organizing pneumonia-intraluminal organization in distal air spaces Patchy distribution Preservation of lung architecture Uniform temporal appearance Mild chronic interstitial inflammation Edematous granulation-type tissue within airspaces: bronchioles and alveolar ducts and alveoli Clinical findings in COP Cough and shortness of breath Relatively short duration of symptoms (1-6 months) Patients often diagnosed first with pneumonia but fail to respond to antibiotics as not infectious etiology Physical exam: PFT’s: restrictive pattern equal sex distribution but nonsmokers outnumber smokers by 2:1. Mean age of onset is 55 yr Continuing weight loss, sweats, chills, intermittent fever, and myalgia are common. Localized or more widespread crackles are frequently present, Histology of COP Patchy areas of consolidation Polypoid plugs of loose organizing connective tissue Architecture of lung is preserved All the connective tissue is the same age Mild to moderate inflammation COP histology From left to right: 1. 2. 3. 4. low-power photomicrograph shows scattered areas of organizing pneumonia. Fibroblast plugs are identified as pale, round structures (arrows) High power photomicrograph shows fibroblast plug in small brochiole High power photomicrograph shows fibroblast plugs streaming from one alveolus to another gross specimen showing branching fibroblast plugs (arrowheads) Images from McAdams et al., 1996 Radiographic features of COP Bilateral or unilateral areas of consolidation Patchy distribution, but in minority of cases may be confined to the subpleural region Small nodular opacities are seen in 10–50% of cases. Lung volumes are normal in up to 75% of cases Radiographic Features in COP Multifocal, bilateral, basilar consolidations Bilateral multifocal consolidations Images from McAdams et al, 1996 CT features of COP Consolidation present in 90% of patients Lower lung zones frequently involved Air bronchograms present with consolidation Mild bronchial dilatation in areas of consolidation CT features in COP Bilateral pulmonary consolidation with subpleural and perbronchovascular predominance and right pleural effusion Images from Lynch et al., 2005 Clinical Course (COP) Majority of patients recover completely with oral corticosteroids Relapse common with steroid taper and/or cessation Acute Interstitial Pneumonia (AIP) Rapidly evolving lesion (days-weeks) Histological findings of diffuse alveolar damage. Therefore, diagnosis of AIP should only be considered after the other causes of DAD (sepsis, shock, etc.) are ruled out. Clinical Findings in AIP Patients often have prior illness suggestive of viral URI Constitutional symptoms: myalgias, arthralgias, fever, chills, malaise Severe dyspnea on exertion developing over days Median time from first symptom to presentation is 3 weeks Hypoxemia progressing rapidly to respiratory failure Mean age of 50 No sex predominance No association with smoking Physical exam: diffuse crackles Lung function tests: restrictive pattern Mechanical ventilation is usually required The majority of patients fulfill the diagnostic clinical criteria for ARDS Histology of AIP Histology: Diffuse alveolar damage Acute phase: Edema and hyaline membranes Organizing phase: Organizing alveolar septal fibrosis and pneumocyte hyperplasia Uniform temporal appearance Histology of AIP Left to right 1. High power photomicrograph demonstrating interstitial widening by edema and inflammatory cells. Hyaline membrane formation also apparent. 2. High power photomicrograph shows organization of the intraalveolar exudate and immature collagen deposition Images from Lynch et al., 2005 Radiographic features of AIP Diffuse bilateral opacities Left: Initial radiograph shows bilateral and basilar consolidation Right: Two weeks later with progressive, diffuse consolidation. Images from McAdams et al., 1996 CT features of AIP Early exudation phase: Organizing stage: Ground glass opacity-bilateral and patchy Consolidation also evident Distortion of bronchovascular bundles Traction bronchiectasis Although CT findings in AIP and ARDS overlap, patients with AIP are more likely to have symmetric lower lobe distribution and a greater prevelance of honeycombing CT features of AIP Diffuse consolidation and air bronchograms Image from McAdams et al., 1996 Clinical Course AIP No proven treatment, corticosteroids often used Mortality rates high (>50%) Those patients who recover may experience recurrence and/or chronic, progressive lung disease Respiratory Bronchiolitis Interstitial Disease (RB-ILD) Respiratory Bronchiolitis: Lesion found in cigarette smokers Characterized by pigmented macrophages in respiratory bronchioles Rarely symptomatic, minor airway dysfunction RB-ILD is defined as the combination of clinically significant pulmonary symptoms, abnormal pulmonary function and imaging abnormalities associated with the pathologic lesion of respiratory bronchiolitis Clinical Findings in RB-ILD Heavy smokers with average exposure of more than 30 pack-years Gradual onset 40-50 years of age Generally mild symptoms of sob and cough (new or changed) Some patients may present with significant dyspnea and hypoxemia Male to female ratio of 2:1 Histology: RB-ILD Histology: Bronchiolocentric alveolar macrophage accumulation Mild bronchiolar/peribronchiolar fibrosis and chronic inflammation Macrophages with “dusty-brown” appearance Figure below: faintly pigmented alveolar macrophages (arrows) fill the lumen of respiratory bronchiole. Mild thickening of respiratory bronchiole wall. Image from Lynch et al., 1996 Radiographic Features of RB-ILD Wall thickening of central or peripheral bronchi (75% of patients) Ground glass opacity (60% of patients) Normal radiograph (14%) Centrilobular emphysema also commonly seen as patients are heavy smokers Radiographic features of RB-ILD Linear opacities in lung bases with atelectasis in right lower lung Image from McAdams et al., 1996 CT features of RB-ILD Centrilobular nodules Patchy ground glass Thickening of central and peripheral airways Upper lobe centrilobular emphysema Air trapping **CT findings in RB-ILD are similar to those seen in other, asymptommatic smokers. However, findings in patients with RB-ILD are usually more extensive CT features in RB-ILD RB-ILD in 41 year old with 30 pack-year smoking history. Widespread gound-glass opacification, with some poorly defined centrilobular nodules (arrowheads) Image from Lynch et al., 2005 Clinical Course RB-ILD Many patients improve after cessation of smoking No reports of progression to dense pulmonary fibrosis Desquamative Interstitial Pneumonia (DIP) Considered to be most likely part of a spectrum of RB-ILD as is associated with smoking and has similar pathology Very rare Named desquamative because the primary finding on histology was thought to be desquamation of epithelial cells. Now recognized as intra-alveolar macrophages Clinical findings in DIP Uncommon Male to female ratio of 2:1 Progressive dyspnea, dry cough May progress to respiratory failure Digital clubbing (40%) Histology of DIP Histology: Uniform involvement of lung parenchyma Accumulation of alveolar macrophages Mild-moderate fibrotic thickening of alveolar septa Mild interstitial chronic inflammation Modest infiltrate including lymphocytes, plasma cells Feature distinguishing DIP from RB is that DIP affects the lung in a uniform diffuse manner and lacks the bronchiolocentric distribution seen in RB. Histology of DIP Photomicrograph shows DIP pattern. Alveolar spaces show diffuse alveolar macrophage accumulation and mild interstitial thickening caused by fibrous connective tissue (arrows) Image from Lynch et al., 2005 Radiographic features of DIP Normal in 3-22% of biopsyproven cases Patchy ground glass opacification Lower zone/peripheral predominance Figure: bilateral, basilar consolidations with no honeycombing or volume loss Image from McAdams et al., 1996 CT features of DIP Ground glass opacification Lower zone distribution (73%), peripheral (59%) Irregular linear opacities and reticular pattern are frequent (59%), usually seen at lung bases Honeycombing (33%) is peripheral and limited CT features of DIP Basal ground glass opacification with multiple peribronchovascular cysts (arrows) Image from Lynch et al., 2005 Clinical Course of DIP The prognosis of DIP is generally good. Most patients improve with smoking cessation and corticosteroids Overall survival is about 70% after 10 yr Lymphoid Interstital Pneumonia (LIP) Very rare condition regarded as a histologic variant of diffuse pulmonary lymphoid hyperplasia Because of its’ rarity, important to do thorough investigation for collagen vascular disease and immunodeficiency Clinical features of LIP Poorly defined clinical presentation More common in women Usually diagnosed in fifth decade Gradual onset over 3 years Symptoms include SOB, fever, weight loss Physical exam: crackles Monoclonal increase in IgG or IgM (75%) Histology of LIP Histology Diffuse interstitial infiltration Alveolar septal distribution Infiltrates mostly t-cells, plasma cells and macrophages Lymphoid hyperplasia frequent Photomicrograph shows LIP. Alveolar walls (arrows) are markedly infiltrated by lymphocytes and plasma cells. Image from Lynch et al., 2005 Radiographic features of LIP Two radiographic patterns: 1. 2. Basilar with alveolar component Diffuse with honeycombing CT features of LIP Dominant finding: ground glass opacity Perivascular cysts or perivascular honeycombing Reticular abnormality (50%) lung nodules Widespread consolidation may occur Diffuse ground glass opacification and multiple lung cysts Image from Lynch et al., 2005 Clinical Course of LIP Corticosteroids used for treatment: 2/3 of patients respond to therapy either with improvement or no progression of disease 1/3 of patients progress to diffuse fibrosis Summary of IIP Most important distinction is between UIP and other IIP’s as prognosis is greatly different Start with thorough history and physical exam looking for possible etiologies of parenchymal lung disease before labeling “idiopathic” Surgical lung biopsy not necessary if confident diagnosis of UIP possible with HRCT Corticosteroids not useful in UIP as it is a fibrotic condition References 1. American Thoracic Society, European Respiratory society Consensus Classification of the Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 2002; 165:277-304 2. Lynch, D., Travis, W., Muller, N., Galvin, J., Hansell, D., Grenier, P., King, T. Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias: CT features. Radiology 2005; 236:10-21 3. Collard, H., King, T. Demystifying idiopathic interstitial pneumonia. Archives of Internal Medicine 2003; 163:17-29 4. McAdams, H., Rosado-de-Christenson, M., Wehunt, W., Fishback, N. The alphabet soup revisited: the chronic interstitial pneumonias in the 1990’s. Radiographics 1996; 16:1009-1033 5. MacDonald, S., Rubens, M., Hansell, D., Copley, S., Desai, S., M. du Bois, R., Nicholson, A., Colby, T., Wells, A. Nonspecific interstitial pneumonia and usual interstitial pneumonia: comparative appearances and diagnostic accuracy of thin-section CT. Radiology 2001; 221:600-605 6. Colby, T. Pathological approach to idiopathic interstitial pneumonias: useful points for clinicians. Breathe 2004; 1:43-49. 7. UpToDate