Theoretical Background Entrenched Enforcement

advertisement

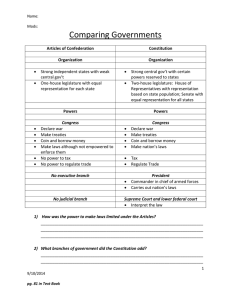

Theoretical Background -Entrenched rules: explicit in Constitution, difficult to alter; purpose: serve coordinating function in society, govern disputes among rulemakers. Also there is a “constitution”—non-entrenched non-textual rules, e.g. statutes passed by governing body; possibly natural law. Both together form a constitution. -Enforcement: no super-gov’t to act as enforcer of Const. People obey it w/o coercion b/c it acts as coordinating device: where expectations are shared it is overwhelmingly in one’s self-interest to comply w/ them (e.g. traffic lights). -Articles of Confederation: purpose—ensure unification of states regarding common foreign/domestic problems but retain state sovereignty. Features: Cong. has power of peace/war, authority to resolve inter-state disputes, regulate/value coinage struck by ind. states, deal w/ Indians, post offices, etc. Problems: 2 of modern nat’l gov’ts most important powers missing: tax power and regulate commerce; no executive or national judicial authority—inability of states to act in concert in matters of nat’l import, multiplicity of laws in several states (e.g. import duties), no enforcement mechanism to ensure state compliance; no Bill of Rights (though this not impetus for Constitution). -Republicanism: (anti-Federalism) entire populace ought to participate in small-scale gov’t to prevent formation of governing elite—civic virtue is paramount. -Federalism: (anti-Republicanism) direct democracy/small gov’t encourages faction of interest groups/political parties. Representative gov’t prevents this. -Separation of Powers: structural federalism protects liberty b/c divided powers check others’ interests—one branch prevents expansion of other in order to preserve own powers. Criticism: akin to fighting monkey problem w/ more monkeys—more possible sources of suppression of liberty. -Federalist 51: Madison’s defense of new Const. expansion fed. powers from AoC. Problems: executive no longer weakest branch, and is now biggest threat to ind. liberty; faction problem still existed w/ emergence of Feds. and D-Republicans; Art. 2 provided for prez and veep from competitors; slavery; women couldn’t vote. -Constitutional adjudication: a function of SC is discussion and clarification of constitutional order, e.g. whether political parties prohibited in Germany. -Legal Process School: seeks to set forth how/why courts should adopt active role in policymaking consistent w/ democratic ideals. Ideas: Law is purposive—Congress trying to achieve goal, cts. should discern purpose and assist law in achieving it (criticism: same problem as authorial intent originalism); relative institutional competence (e.g. dormant CC)—cts. adjudicate among actors who should do what re: law; cts. should legitimate gov’t action by requiring procedures; re: SoP, should facilitate institutional coordination to effectuate government, rather than simply policing SoP mindlessly; re: dormant CC, care about effects of court enforcement and general economic effects of having it, rather than the precise nature of the language used. Judicial Power/Judicial Review: power to determine constitutionality of statutes & executive action. -Arguments for judicial review: (1) Const. meant to impose limits on gov’t powers of 3 branches, meaningless w/o judicial enforcement (counter: ct. cannot enforce (Worcester v. Georgia); any branch can interpret). Against: departmentalism negatives need for the power (counter: situations like Civil War arise—but is this good or bad? Depends on desire for stability vs. principle). (2) Power to decide cases “arising under” Const. + supremacy clause judicial review. Against: could just interpret/apply fed. statutes to decide cases and evaluate const. of state statutes but not fed. ones. Marbury args.: judges violate oath if enforced unconst. laws (this begs question); supremacy cl. (could just mean Congress should conform to const.’s restrictions). -Stuart v. Laird: Congress has power from Art. 3 to (a) establish/abolish inferior federal courts & (b) transfer power between them. Judiciary Act of 1801 abolished circuit riding/created new courts/judges. Incoming Republicans concerned with these new courts filled with federalist judges, so passed JA of 1802, eliminating these Art. III judgeships, reinstituting circuit riding (an SC justice too). Court: Art. III apparently allows Congress to make whatever inferior tribunals it wants & can transfer power btwn them; also, “practice & acquiescence” to practice since inception of judicial system. Like Marbury est. judicial review but also marked SC acceptance of Republican hegemony. -Mandatory view of Art. 3: the judicial power shall be vested in some fed. judiciary—if not poured out into other courts must remain in SC. Historically this view rejected by Congress (e.g. limits on fed. diversity jurisdiction—Congress in §1332 gives less diversity jurisdiction than Art. 3 permits). -Marbury v. Madison: Struck down part of JA of 1789—it authorized juris. to hear Marbury, but Congress cannot expand court’s original juris. beyond original const. boundaries—in this case to hear petition for writ of mandamus. If could then Art. III enumeration “mere surplusage,” w/o meaning (criticism: could just be floor rather than ceiling, a la argument re: enforcement powers—rights enumerated are floor, not ceiling, so Congress ought to be able to expand). -Lessons: (1) Congress can add/remove from SC appellate juris. but not original. (2) SC can enforce const. limits against Congress, including Art.3 (3) SC can compel exec. officials to do certain tasks as long as those are duty and not discretionary to executive (e.g. U.S. v. Nixon—comply w/ subpoena). (4) Judicial review—established power of judiciary to review const. of executive and legislative (fed. statutes) actions. (5) Stuart and Marbury are united by SC’s reluctance to enter serious confrontation w/ executive branch; instead gave Republican purge of Federalists blessing of law. -Cooper v. Aaron: Arkansas school failed to comply w/ ct. order to desegregate after Brown v. Board 2. Reasserted judicial review power against AK’s contention that it was bound only by Const—not SC’s interpretation of it. Ct.’s strong statement came after prez. sent in nat’l guard, in contrast to guarded statement of Brown 1—SC can only maintain legitimacy through appearance of power—no enforcement mechanism! -Dred Scott v. Sanford: no diversity juris. b/c Scott not “citizen” w/in meaning of Art.3. Originalist/textualist arg. Would have been DP violation if had been freed during sojourn to non-slavery state. Instance where judicial review disastrous consequences (Civil War—thanks to departmentalism too). -Lochner v. NY: regulation of bakers’ hours under police power unconst. Skeptical court used rational basis scrutiny (legitimate ends, reasonably tailored means) b/c substantive due process right to contract/sell labor affected: failed this b/c not intended to protect bakers’ health nor necessary to do so (uncharacteristic lack of deference). -Problem of judicial supremacy vs. deference to legislature/people: solved by Carolene Products notion of tiers of scrutiny. Normally rational basis (legitimate means, rational means-end relation, deferential b/c legislative process sufficient for procedural DP), unless apparently insufficient process indicates reason to heighten scrutiny: (1) discrete & insular minority that cannot defend self through democratic process (2) law prevents democratic/legis. process from normal functioning (e.g. poll tax). -Departmentalism: view that Congress, prez, and Court each individually must evaluate constitutionality of e.g. punishing seditious speech—cannot punt to court after legislating or prosecuting. Motivation: judicial supremacy + rational basis scrutiny risk of under-enforcement of const. norms (only judiciary scrutinizes and doesn’t do so harshly, even if gets through barrier of justiciability reqs.). Other branches can pick up slack e.g. Lincoln after Dred Scott! Executive Power: 3 sources: (1) Art. 2 of Const. (vague), (2) What Congress determines/expresses by legislation, (3) inherent powers? -Is there inherent (i.e. not pursuant to express/implied const./statutory authority) presidential power? 4 approaches (Youngstown): --(1) No inherent prez power: prez may act only if express/implied const./statutory authority (Black’s majority opinion). --(2) Interstitial executive power: prez has inherent authority unless prez interferes w/usurps powers of another gov’t branch (Douglas’ concurrence). --(3) Legis. accountability: Prez may exercise inherent powers so long as he doesn’t violate statute or Const. (Jackson’s conc.). Three zones of prez authority: acts pursuant to Cong. authorization (generally legislation), against its will, or middle twilight zone; judicial review standard adj. accordingly. Very influential! --(4) Stewardship theory of exec. power: prez has inherent powers that cannot be restricted by Cong.; may act unless violates Const. (e.g. foreign policy—but see Medellin). -Youngstown Sheet v. Sawyer: Truman seized nation’s steel mills during Korean War pursuant to Comm.-in-Chief power when strike threatened. Jackson (conc.) expresses concern over “imperial presidency”—Art. 2 powers + political influence via party. On Jackson’s view (3): Congress implicitly denied consent to prez action here by rejecting putting power in contemplated legislation that would have granted it (vs. Cong. silence—if area of trad. prez authority then silence might imply tacit authorization). -Dames & More v. Regan: Practically, Prez given more leeway by ct. on issues of nat’l security or foreign policy (see view (4)—may be extra-const. inherent powers in those zones). Prez lifted freeze on Iranian assets in US in agreement for release of American hostages in Iran. Versus Youngstown: seizure is legis. action, transfer of claims isn’t; no contemplated legislation to draw implied attitude of Congress from. -Medallin v. Texas: Vienna Convention must be implemented by domestic legislation—prez lacks executive power to give non-self-executing treaty effect. -Hamdi v. Rumsfeld: plurality held prez has power to detain enemy combatants indefinitely b/c AUMF statute showed Cong. approval (Youngstown framework). Souter dissents, interpreting AUMF differently. Only after this executive power established does question of Hamdi’s due process right (review of detention) enter. Court finds curtailed DP review due to him. -Hamdan v. Rumsfeld: held prez does NOT have power to try non-citizen via special military tribunal b/c Cong. disapproved via UCMJ (maj.) and (plurality) UCMJ through lense of Geneva Convention—law of nations, vs. American common law of war. These tribunals need to meet certain criteria to be fair (e.g. cannot be held in absentia). -Boumediene: Ct. drops pretext that it was protecting Cong. from executive overreaching; habeas restrictions (on territory of sovereign) unconstitutional under Suspension Clause. Using Congress as justification made it look as though ct. wasn’t undermining nat’l security, acting humbly, and deciding on narrow statutory grounds. -U.S. v. Nixon created domestic privilege subject to balancing test; can encompass almost anything; strongest where exec. makes claim of exec. privilege in regard to particular disclosure (Nixon didn’t). Clinton v. Jones: no immunity to civil proceedings re: prior conduct b/c interest less strong (no need to safeguard unofficial conduct). Legislative Power: Art. I imposes 2 reqs. on legislative action: bicameralism (action by both chambers of Congress) and presentment (bill goes to prez to sign or veto). -INS v. Chadha: (limits on legislative veto) immigration judge (executive) determines whether illegal imm. deported; AG then has total discretion to enforce/overturn judgment. IJ stayed Chadha’s deportation, House introduced resolution vetoing IJ’s decision. Court found unconstitutional b/c no bicameralism (only one house) and no presentment. Essential that Congress found that veto essentially legislative in purpose and effect—altered legal rights, duties, relations of persons (both Chadha and officials involved). White’s Dissent: Legis. veto enmeshed in politics; here no threat of tyranny. -Chadha’s DP a major concern. Basic due process requirements (notice/hearing/neutral DM) can possibly replace e.g. non-Art. 3 courts in Guam/Samoa. -Appointment: Art. II § 2.2: Executive power to nominate Officers requires “advice and consent of the senate” but as w/ special prosecutor in Morrison can vest appointment of inferior officers (hired & supervised by Officer) (or “mere employees”) in Prez, courts, or dep’t heads. -Removal: Art. 2 § 4: impeachment of executive persons. 4 rejected approaches: (1) Symmetry: whoever appoints can remove; (2) Removal is inherently executive function (Myers use of “take care” clause) (Taft, Scalia, Thomas); (3) Impeachment by Cong. from Art. II only; (4) Congress specifies in provision for each position pursuant to N&P cl. --Myers v. US: removal of executive officers (here postmaster) is solely executive function & must be done by president, where exec. power is solely vested in “take Care” cl. Congressional act providing that can be removed only “with advice & consent of Senate”—congressional limits on removal power—is unconst. interference w/ exec. power. --Humphrey’s Executor v. US: only purely (vs. quasi-, e.g. policymaking Fed. Trade Comm.) exec. Officers under Presidential power such that removal restrictions apply. Otherwise Congress can under Art. I create independent agencies/insulate members from presidential removal unless for good cause if quasi-legis. or quasi-judicial. --Bowsher v. Synar: Comptroller-General is head of Gen. Accountability Office, watchdog of Congress. Removable by Cong. for cause. Though legis. told to exercise lots of discretion in duty by GRH Act, i.e. execute the Act. Court found congress having removal power here was impermissible delegation of executive power to legislative official (CG) (b/c insulated from presidential removal). Criticism: if mere implementation of GRHA = execution, this is absurdly broad definition of “execute.” --Morrison v. Olson: creation of (executive) special prosecutor for high-ranking gov’t officials who violate fed. law, appointed by judicial Special Division at AG’s instigation. Powerful ind. counsel, difficult to remove (impeachment by AG/good cause only). (1) Is IC an Officer or inferior Officer? If Officer, good cause restriction problem under Myers. Even though doesn’t report to anyone court considers inferior officer b/c limited jurisdiction, tenure, and subordinate to AG’s ability to remove. (2) Even in an IO, is cross-branch appointment by courts okay? Incongruity standard for CBAs: no incongruity btwn pros. and court appointing. (3) Does overall scheme violate sep. of powers by undermining exec. authority (& inconsistent w/ Myers to make removable only for good cause)? Ct. rejects formalism of Myers and Humphrey’s for functionalist approach: does the restriction impede/impermissibly undermine Prez’ ability to faithfully execute the laws? No. Also no aggrandizement issue b/c legis. not taking more power but curtailing executive’s by giving to judiciary. Vs. Bowsher: no Congressional role in removal; independence of IC from prez desired Cong. can limit remov. power. ---Modern Approach: no Congressional participation in removal of pure Officer, but what is Officer determined by functionalist approach: what power does President need to do his job? Prevention of aggrandizement: expansion of one branch’s powers at expense of another. ----Nondelegation doctrine: Congress, because invested with sole legis. power, cannot delegate it to executive administrative agencies b/c would violate sep. of powers. Delegation is implied power only if Congress provides intelligible principle guiding administrative action—very weak standard! Trends regarding removal power in regard to Separation of Powers: --(1) Emphasis on nexus btwn removal power & power of control over person to be removed: control requires removal (Myers); flipside is power to remove influences court to conclude you control (Morrison (Scalia dissents), Bowsher—CG removable by Congress thus legislative officer). --(2) “For cause/good cause” removal restrictions not significant impediment to executive having required exclusive control of an Officer (Morrison—didn’t impermissibly undermine; Bowsher—control over CG not very restrictive; Humphrey’s—restriction on removal of FCC commissioner. --(3) Move away from formalistic categorization approach to sep. of powers (Morrison—rather ask how much power prez needs to do job; Myers—quasi-categorizations) --(4) “Inferior officer” very broadly defined (most officials are this) (Morrison—IC did not seem very inferior). --(5) Congress can limit removal by prez to good cause (esp. where indep. from prez is desirable), but cannot prohibit completely; nor can it give self sole power to remove Const. adjudication approaches: Counter-majoritarian dilemma: judicial review is CM/anti-democratic b/c founders overrule statutes enacted by popular vote/representation. Yet Constitution also purports to grant sovereign authority to people. -2 major questions (Bickel): (1) Whether/when it’s approp. for judges to overrule majority (see protected classes from Carolene Prod./fundamental rights); (2) How can others prevent judicial tyranny/keep court in proper place? --Rests on questionable assumptions: (1) equates democracy w/ majority rule. (2) Assumes laws enacted by elected representatives must reflect majority will (corporate hegemony, impossibility theorem: mathematically impossible to translate majority will into coinciding policy outcomes b/c of confounding intermediaries); Against dilemma (Dahl): (1) Historically courts never resist majority will overlong; sometimes lags (e.g. Lochner era) but substantive operations of formal legal apparatus updated by replacement of justices/political pressure. (2) Flipside that Court never stands up for rights in face of majority opposition—see e.g. Korematsu, Dred Scott. Advantage of constitutionalism vs. parliamentarianism: stability! General argument that political considerations prefigure adjudication—e.g. Marbury, Stuart, Lochner-era court (economic theory, popular opinion, or power of other branches). -Interpretivism: const. adjudication just is interpretation of text, regardless of particular interpretive approach. Approaches: --(1) Textualism: uses grammatical rules, original understanding of Founders of words, dictionaries from time; overlap w/ originalism; purposivist criticism: does “no vehicles on the grass” also cover wheelchairs? --(2) Purposivism: what was purpose of legislature in using certain words/phrasings? --(3) Originalism: I. Authorial intent: belied by inability to impute single intention to 500 people; furthermore, literary theory allows meanings never intended by authors. II. Public understanding (supplants AI): soft originalism = general sense of purposes/aspirations; hard originalism = particular questions regarding portions of Const. Arguments for originalism: founding was special event transcending normal democratic procedures and deliberative care, so should bind us; saves us from judicial tyranny of unelected, unaccountable judges (counter: this is all judicial review). Criticism: “law office history” reduces complex narratives to superficial representations through taking preferred narratives at face value to support preordained conclusion; no supermajority representing all parties (women, slaves, non-propertied). Dispute w/ A-O basically over whether amendment (cumbersome, safe) or interp. is proper means of Const. evolution! Did framers intend A-O (via nat. rights)? --(4) Anti-originalism: Const. is living document meant to be interpreted in context of current times re: public good; also covers pragmatism --(5) Structuralism: how do structures of text fit together in best, most coherent manner (against Scalia’s ignoring first clause of A.2). -Dworkin: judges ought to provide best constructive account of existing legal materials by putting text/precedents in best possible light: (a) fit existing materials and (b) justify them by making them sensible and good rather than senseless and bad. --(6) Natural Law: unwritten const. composed of fundamental “natural law” principles enforceable against states even if not in text. Justiciability—Art. 3 Limits on Judicial Power: advisory opinions, standing, ripeness/mootness, political question doctrine. Ways court can duck difficult cases. -Args. for: protect SoP, conserve judicial resources, improve decision making w/ concrete controversies suited for jud. resolution, fairness: prevent adj. of rights of persons not present (see e.g. class actions); yet these considerations must be balanced against need for judicial review. Tension btwn flexibility and predictability in doctrines. -Advisory opinions: questions must arise out of case/controversy. Cannot issue pre-enactment opinions on legislation, lack of standing/ripeness etc., and cannot review state ct. judgments having adequate/independent basis in state law such that decision will only affect fed. law. -Standing: Args. for: promotes SoP by restricting availability of JR (careful not to go too far), serves jud. efficiency by preventing ideological suits, improve judicial decision making by concretizing issue, fairness (won’t affect rights of non-parties). 2 types of standing limitations: --1. Prudential: general rules against 3rd party standing (cannot assert rights of others); generalized grievances (no standing where same injury as everyone else in country— appropriate forum is legislature; preserves SoP); zone of interest test: must be w/in class intended to benefit from statute (esp. review of agency decisions under APA). --2. Constitutional: ---(A) Injury-in fact: injury must be concrete/actual/imminent, not merely abstract/hypothetical. Criticism: how can this be a factual inquiry when which subjective categories of injury ought to be recognized is legal/policy judgment at ct.’s arbitrary discretion? ---(B) Causation: injury must be “fairly traceable” to challenged action. Allen v. Wright: fed. money going to racist school not unconst.—no right to lawful behavior by gov’t (gen. grievance); stigmatic injury: effect of institutional discrimination on black persons no standing, must be concrete; denial of/interference w/ right to desegregated education: affirmed in Brown but here no standing b/c schools might still discriminate w/o money (but whole reason gov’t subsidizes activities is to encourage them!) Dumb case. Note: causation/redressability analyses often identical. Criticism (redress. too): can’t be properly made on basis of pleadings, unprincipled b/c depends on how ct. characterizes injury (compare cases!), unprincipled b/c deals w/ probability continuum court not equipped to engage with. ---(C) Redressability: remedy must be likely to follow from favorable decision. Regents of UC v. Bakke: no chance to compete for spots set aside for non-white applicants is injury redressable by having opportunity to compete. Linda R.S. v. Richard D.: increased probability of getting child support not suff. to satisfy redress. req.; ct. presumes threat of criminal prosecution will not influence behavior! Dumber case—reductio would prevent standing for anyone! Role of non-const. considerations, e.g. pet.’s race? --Lujan v. Defenders of Wildlife: (purely procedural injury) sued for application of Endangered Species Act overseas; act provides for any citizen to challenge violations of it. Scalia found no standing b/c purely procedural injury—no standing unless (a) legis. provides for universal procedural standing and (b) also harm to concrete interest— would have been okay if e.g. petitioners gave evidence of plans to visit countries like a plane ticket! Criticism: isn’t this, like magic boilerplate, a superficial req.? Also, why shouldn’t knowledge of death of species be enough? Scalia: requiring enforcement of procedures impinges on Exec. authority from Take Care cl. Criticism: Ct. taking power from Congress who writes laws in first place. Blackmun’s dissent: Congress’ provision for purely procedural standing has substantive ends determined by it—removing disrupts litigation against admin. agencies. --FEC v. Akins: (generalized grievance) GG okay/satisfies IIF req. if isn’t too abstract; if (a) widely shared & (b) of abstract and indefinite nature, then no IIF. Disclosure of info by AIPAC pursuant to FEC regulations providing for such disclosure. Distinguish from U.S. v. Richardson: denial of access to CIA info gives no standing b/c no statute seeking to protect citizens from that sort of injury (Cong. in creating right can provide for enforcement of that right in manner of choosing; did in Akins but not Richardson). Lesson from Akins: Congress can give right to sue by including e.g. “information must be made available to public”—concretizing an otherwise procedural injury. --Massachusetts v. EPA: affirms “ecological nexus” test to satisfy C/R rejected in Lujan (emissionsglobal warmingcoastline recession). EPA’s failure to regulate emissions need not be but-for (nec.) cause to have nexus—reduction of risk is sufficient. Distinguishable: federalism concern b/c MA has “quasi-sovereign” interest in protecting its sovereign territory. Maybe limited to state suing, or maybe liberal court would expand standing to include non-state actors. -Ripeness/Mootness: facts supporting standing have yet to develop (ripeness); standing existed at prior point (mootness). Ripeness Standing Mootness. --Ripeness: Factors: (1) Are there non-factual issues for judicial decision? (2) What is hardship in requiring parties to wait (does challenged law require immediate & significant change in behavior; are there serious penalties for non-compliance?). City of LA v. Lyons: speculation that might be put in LAPD chokehold in future not ripe. Criticism: no-one can pursue injunction against LAPD then! Defunis v. Odegaard: cannot decide questions that cannot affect rights of litigants in case before ct. (here in final semester of law school so denial of admission a non-justiciable question). --Mootness: Ct. will consider moot case where (1) Voluntary cessation of allegedly illegal conduct (after injunctive relief obtained; e.g. suspension of an AA policy every time litigation portends) (2) Capable of repetition yet evading review (Roe v. Wade). -Political Questions: case non-justiciable where (from Baker): (1) Textually demonstrable Const. commitment of issue to coordinate political dep’t; (2) Lack of judicially disc./manageable standards for resolving it; (3) impossibility of deciding w/o initial policy determination not w/in judicial discretion; (4) would cause court to disrespect coordinate bracnhes of gov’t. ***Areas applied in: foreign affairs, Guaran. cl., electoral process, Congress’ internal processes, impeachment. Arguments for: fed. judiciary avoids controversial questions, limits courts imposition on democracy (CMD), relative institutional competence, danger of fed. court’s self-interest in reviewing amendment process, separation of powers grounds; Arguments against: judicial role to enforce const./preserve matters from majoritarian interference, fed. courts robustly credible, equates deference with abdication. Source: constitutional (SoP, textual commitments) or prudential (preserve credibility, democracy concerns)? --Baker v. Carr: meaning of Guarantee Cl. (“Republican form of gov’t) has no judicially-manageable standards b/c meaning too unclear (Luther v. Borden) (versus EP cl., which does). Malapportionment of state legislatures invokes EP cl., not Guarantee cl. Frankfurter’s dissent: too abstract for judges; for electorate to decide. Also, EP clause just as vague as GCl—why judicial standards developed for one but not the other? --Nixon v. U.S.: Question whether “try” in Impeachment cl. mandates trial by whole Senate non-justic. b/c mpeachment is legs. sole check on judiciary and would be conflict of interest. Souter: ct. has some discretion re: impeachment, e.g. flipping a coin unacceptable (“sanity check”). Committee standard clearly okay. --Powell v. McCormack: does “each House shall be Judge of Qualification of its own Members” allow House to exclude rep. from taking seat? political question? No— textual commit. of issue to House is to narrow scope of judging qualifications. Imp’t distinction: Nixon—no discretion; Powell—limited scope of discretion. --Bush v. Gore: Differential counting measures is violation of EP clause; remedy is to halt recount. Political question b/c SC basically saying it doesn’t think Florida could do a const. recount, so it can’t. Death of PQ doctrine! Was tool of institutional survival in Marbury where non-compliance was feared; so such issue here. Federalism—Enumerated Powers: Federalism: vertical division of power (vs. horizontal of SoP) and subject matter juris. between multiple gov’ts. -Purported virtues: (1) like SoP, splitting gov’t protects against tyranny by preventing use of power for individual purposes (mathematical Two State Markhov model—less likely system will align); (2) market of gov’ts among which citizens can shop; Tiebout hypothesis—jurisdictional competition will maximize choice-satisfaction through specialization; criticisms: where’s the empirical support? Aggregate welfare demands restraint but tragedy of commons re: taxes, environmental regulation, etc. Practical criticism: fed. gov’t far better at protecting civil rights! -Enumerated powers: only specifically enumerated powers in Const. text belong to fed. gov’t; all others belong to states/people. (A.10, N&P cl., S cl.) -McCulloch v. Maryland: Marshall enlarges enum. powers against states/cramps state power against fed. in context of whether fed. gov’t can make nat’l bank/states tax it? --10th Amendment: “powers not delegated to US by Const., nor prohibited by it to States, are reserved to States respectively, or to people. Marshall overcomes: (a) textualism: “expressly” omitted though was in AoC framers did not intend to deny Congress implied powers the lack of which hobbled fed. gov’t under Articles; (b) structuralism: giving Congress powers must have ability to use them—need roads leading to the post office. --Necessary & Proper Clause: Congress will have powers not explicit in constitution N&P for carrying out enumerated ones. However, “necessary” ought to mean strictly construed, not efficacious. Marshall overcomes: strict construction would strangle ability to thrive/react to crises or modern exigencies; would make court absurdly powerful b/c would have to evaluate every law to find out whether necessary. Makes N&P cl. font of power rather than restr. --Supremacy Clause: (Art. VI § 2) Const./treaties/Congress’ laws are supreme. Marshall uses this rather than N&P cl. to justify untaxed nat’l bank. Invokes S. cl. where relevant federal interests at stake that Congress has made no move to protect—here MD’s power to tax, which is power to destroy. Destroy what? Unclear here. S. cl. becomes protective barrier for fed. gov’t interests. Commerce Clause: Why do we need it? (1) Pure coordination problem: horrible logistical problems where each state e.g. has own trucking regs.; difficult to work out w/o overarching representative authority (fed. gov’t). (2) Tragedy of commons: aggregate incentive to cooperate (e.g. we need environmental regs.) but individual incentive not to everyone cheats and everyone worse off. Arguments for restricting: federalism concerns (outdated), --Stage 1: (formalism)—Schechter Poultry: codes of fair comp. for poultry ind. voluntarily adopted by supermajority. Chickens come from other states but go to butchers intrastate. Not in ISC did it have direct effect on ISC? Carter v. Carter Coal: direct effect must be proximate cause. Also, commercial (Wall Street) vs. non-commercial (agriculture, mining, mnfctg) distinction. Hammer v. Dagenhart: Anti-deferential approach: Ct. struck down fed. reg. of child labor b/c economic pretext for usurping state police power. Ex. of Lochner problem of cts. using economic theory to abrogate legislative policy rational basis review created to void this problem (and strict standing reqs. meant to prevent overrule of New Deal legis). Note this case relied on outdated, stronger interpretation of A.10 (fewer federalism concerns today). --Stage 2: (transition)—NLRB v. Jones & Laughlin Steel: Robert’s SITTS9. NLRB established right to unionize via CC. Direct/indirect test becomes degree of relation test: intrastate activities must have close & substantial relation to ISC that control is essential/appropriate to protect ISC from obstructions. Labor unrest disrupts IS markets, even though this is indirect effect for all but huge industries. --Stage 3: (modern)—Wickard v. Filburn: Agr. Adj. Act reduce wheat supply b/c exportation dropped. Filburn exceeded quot for personal use. Effect on ISC? Aggregation principle: personal effect on ISC negligible but aggregate effect is “substantial.” Criticism: everything now regulatable! Heart of Atlanta Motel & Katzenbach v. McClung: Civil Rights Act of 1964 desegregating public goods/services (hotel & restaurant here) okay. Ct. employed rational basis review (legitimate ends, reasonably tailored means) and deference (accepting legis. purported reasons) to legis. Lip-service to direct effect language; use of aggregation principle. --Stage 4: (neoclassical)—U.S. v. Lopez: GFSZ Act—fed. offense to possess firearm in school zone—unconstitutional. 4 doctrinal themes: (1) Return to commerce/noncommerce distinction as economic/non-economic. (2) Federalism concern in areas of trad. state sovereignty (here education, crime). (3) Limitation of aggregation principle—slippery slope leading to reg. of any behavior (why is this bad?). Aggregation okay if of economic units. (4) Undermines RB review from stage 3: “substantial effect” req. direct/indirect test from stage 1. Slippery-slope: if can regulate this can regulate anything of state’s—federalism concerns. Problem: federalism doesn’t supply standard by which to limit CC power in principled manner. Souter/Breyer dissent: this is categorical formalism and so not aligned w/ real federalism/economic concerns. Adding “guns that pass through ISC” (magic boilerplate) would make const.! Hamilton in Fed. Papers argues expansion of fed. powers is natural tendency where people gain trust of nat’l gov’t ‘s capacity for effective administration (this could just be rationalization). ---New Federalism (Souter): A.17 (direct election of senators vs. appointment) and A.14 purposefully amend away prior intention that states could protect from fed. intervention. Against this: old federalism saw individual liberty protected by structural constitution (e.g. sep. of powers) strict reading of Rec. Amendments. ---U.S. v. Morrison: Violence Against Women Act—civil remedy for gender-motivated violence not w/in CC power. Criticism: why isn’t this analogous to civil rights in stage 3? Maybe: no economic nexus, b/c no “demand” for violence against women; or, ct. exercising political judgment traditionally reserved to legis. Less deferential RB review: rather than accepting legis. conclusion re: existence of “substantial effect,” Ct. asks itself if it agrees there is such effect. ---Possible explanation for Stage 4: more federalism-concerned conservative justices on court (note that rulings generally 5-4). ---Ways to make VAWA constitutional: (a) add “substantially effect ISC” to statute; (b) add jurisdictional predicate, e.g. “perpetrated in manner using public accommodations involved in ISC.”; (c) include more findings of fact re: effect on ISC. Stage 5?: Gonzalez v. Raich: Cali legalized med. marijuana; challenged const. of fed. statute banning on ISC grounds; ct. found Cali statute unconst. Is this a return to deference of stage 3? Result-driven judgment? Factual similarity to Wickard? Tax & Spend Power: (Art. I § 8) Congress has power to provide for “general Welfare of the U.S.” More power to spend than regulate incentivize w/ $. -U.S. v. Butler: Agricultural Adjustment Act w/ subsidy for compliance by limiting crop yields (stabilize production) found to be unconst. coercive—seeking to regulate through purchase subject reserved to states (agriculture). This case is clearly no longer the standard. Madison: T&S power limited to legis. fields enumerated to Congress; Hamilton: so long as no other const. provision violated, power used for general welfare (akin to current view). -Steward Machine Co. v. Davis: tax credit to employers cooperating w/ fed. unemployment compensation program const./non-coercive. Test: same goal must be met by fiscal need served by tax & alternative behavior to be encouraged/discouraged. Unhelpful test and hard to reconcile this w/ Butler! -South Dakota v. Dole: conditioning fed. highway money on 21-yr.-old drinking age okay. 4 very permissive rules for TSP: (1) Must be in pursuit of general welfare—useless as limiting device b/c defer to legis. to determine/what isn’t?! (2) Must be unambiguous about conditioning states’ receipt of fund (3) Conditions must be related to fed. interest in particular nat’l projects/programs (4) Conditional grant can be barred by other const. provisions e.g. A.1 -Similarities to CC: tipped balance of power to fed. gov’t, esp. w/ A.16 (income taxes); difficult to formulate principled restraints (categorical formalism predominates). Enforcement Power: (A.14 § 5) Congress has power to enforce Reconstruction Amendments (13-15) by “appropriate legislation.” Cong, interpretation? -Katzenbach v. Morgan: Voting Rights Act prohibited NY from having English proficiency reqs. for voting (problem: Lassiter held them not unconst. under 14th/15th Amends.) Solution: Congress has enforcement power pursuant to own understanding of A.15, not court’s. Basically rational basis review—much deference, need only perceive possible RB for connection btwn A.15 and legislation. (Also, Katzenbach concerned Puerto Ricans—no RB!). Adopts nationalist view: can expand scope of rights. -City of Boerne v. Flores: Smith held no religious exception to peyote prohibition under Free Exercise cl.—facially neutral laws disproportionately affecting one religious group okay (rational basis test). Congress got mad & passed Religious Freedom Restoration Act to reinstitute prior SS test. Ct. reasserted judicial supremacy (less than did in Marbury—against changing A.14 via reinterpreting it) probably b/c Congress directly challenged it. Adopts federalist view: cannot create new/expand scope of rights. Criticisms of view: Const. protection of rights is floor, not ceiling—textual evidence in A.9.; Kennedy begs question of meaning of “enforce” in § 5, and misconstrues Marbury (no right found in Const. =!=> Congress cannot create one). --Under A.15 § 5, Congress can: (1) Impose penalties for violations of A.14 as interpreted by courts. (2) Adopt remedial measures, e.g. affirmative action (3) adopt prophylactic/preventative measures; (2 & 3) must meet following reqs.: (a) congruence/proportionality (no gender disc. in response to racial); (b) there is pattern of past violations—Congress must show this. However, as of Boerne, cannot expand scope of rights/create new ones. -Principles: (1) Less deference where Congressional interpretation against background of established judicial interpretation (e.g. Est. cl. in Boerne). (2) Grandfathering—old legis. based on Cong. interp. before ct. decided const. okay, but similar future legis. not okay. (3) Ct. may be influenced by Cong. interp. in order to avoid conflicts with preexisting legislation—is this what “deference” means? -Judicial supremacy is not symmetrical: legis. self-imposition of limitation ct. has not yet imposed is okay; stepping beyond ct.-construed powers invokes ct. action. Fed. Regulation of State/Local Gov’ts: SC: A.10 is just reassuring tautology; limits on fed. interference w/ state gov’ts from federalism read into const. structure (note that had more teeth before Hammer v. Dagenhart was overruled by US v. Darby, as that case used A.10 as limit on CC power). -What are federalism limitations on Cong. power? (1) Commerce cl. jurisprudence (2) If not reg. of private party but state analysis here. -10th Amendment: (O’Connor) though tautological, evidence/reminder of concerns & principles established by const. structure, i.e. federalism & state sovereignty. -1. Anti-commandeering principle: Congress cannot conscript state gov’ts as agents for own purposes; can however (a) preempt and (b) incentivize monetarily to achieve identical outcome. Note: state enforcement of federal law is NOT federal commandeering. -2. Imposition of financial burdens: Murky! Fed. cannot impose financial burdens on states (regulate states qua states), but issues unfunded mandates frequently. However, monetary incentives always okay, even if something like Medicaid where so necessary that is almost coercive to withhold. -Phase 1: Nat’l League of Cities v. Usery: FLSA not enforceable against states, even via commerce cl., where regulates areas of trad’l state gov’t functions (wages/hours of state employees). -Phase 2: Garcia v. San Antonio: overruled Usery. No test nec. b/c state interest/functions protected by procedural safeguards in structure of gov’t at fed. level—i.e. representation in political process. Note analogy to arguments in Lopez & U.S. v. Morrison (also dissent in Morrison: power shift to fed. via A.17 & A.14). -Phase 3: Gregory v. Ashcroft: mandatory retirement provisions for appointed state judges not covered by fed. ADEA b/c state’s retirement provision is “decision of most fundamental sort for sovereign entity”—if Congress wants to affect it must preempt it. --NY v. U.S.: fed. approved compromise by states re: disposal of radioactive waste meant to incentivize ind. state disposal. Monetary incentive (surcharge returned for compliance) & access incentive (eventually access denied to existing sites) okay; but “take title” provision (state unable to dispose of own waste by certain time must take possession of it) is choice btwn 2 unconst. alternatives: (a) regulate way Congress tells them to (violates AC principle) or (b) dispose of waste themselves (imposes financial burden). Issue: states consented & even asked fed. to do this! Arguments: (1) Separation of powers: goal of const. is prevention of tyranny—interests of people, not states alone. Hence sep. of powers as safeguard cannot be breached even by states’ consent. (2) Mutual incentive to avoid responsibility: States have incentive to embrace fed. reg. to avoid responsibility for results where the reg. would be necessary anyway—fed. has incentive to shift responsibility of choosing actual site to states (counter: underestimates perception of voters who attack incumbents; fed. gov’t clearly could specify manner of state enforce.). Steven’s dissent: Congress can command states re: RRs, schools, prisons, elections—why not here? --Printz v. U.S.: Brady Act requiring state “chief LE officers” to make reas. effort to find out whether gun poss. would violate law is unconst. Scalia: (1) conscription of state LE frightfully augments fed. gov’t power; (2) Having CLEOs execute fed. law w/o prez control abrogates prez power guarantee under Take Care cl. (counter: TC cl. more sensibly read as job responsibility of prez rather than guarantee of powers) (3) Reasons against commandeering state legis. (NY) militate against same for CLEOs (policymaking distinction rejected b/c executive action always requires some policymaking). ---Note: state judicial officials often enforce fed. law—why not state exec./legis. ones? Arguments for this: (1) local officials better for enforcing larger policy b/c more sensitive to local needs than fed. bureaucracy. (2) More enforcement by fed. gov’t more fed. power—precisely Scalia’s concern. --Reno v. Condon: fed. statute prohibiting disclosure of driving info by states to commercial entities okay. Distinguish from NY & Printz: generally applicable—targets states as suppliers & private resellers; yet this is classic police power area. Probably just ct. drawing in state abrogation of fed. power . Prohibition of conduct, not affirmative mandate as was in NY & Printz. So where prohibits state gov’ts from engaging in harmful conduct/covers private parties too, okay; affirmative duties imposed, not okay. --Missouri v. Holland: fed. legis. made pursuant to treaty power okay where major nat’l interest protectable only in that way (protection of migratory birds/ecology). Dormant Commerce Clause: commerce clause limitation on power of states (original intent arg.: fnders intended exclusive grant of power to Congress). -Arguments for Court using: (1) Free trade is desirable and court enforcement facilitates it ([a] states will race to bottom b/c necessity of protectionism; [b] pure coordination problem: coordinating fed. framework to ensure transactional ease—AoC failed!) (2) Congress needs help—too much legislative inertia, and court has relative institutional competence (legal process school)—court can react at local level; Congress works a priori, ponderous to respond). (3) Congressional silence even though could have prevented court by statute (could also have authorized by statute, however). Also, one should not be harmed by laws in states where one lacks political represent. -Arguments against having it: no textual provision for it included, interferes w/ Congressional authority/SoP. -Meant to prevent state protectionism by discriminating against out of state actors. 3 types of discrimination: (1) Facial—all out-of-state actors d’ed against—strict scrutiny (strong pres. of invalidity) (2) Discriminatory Purpose—even though never brought out in cases oftentimes the Court, apprehending apparently discriminatory intent, subjects to strict scrutiny. (3) Effective Discrimination. Which invokes which test is not always clear! -Framework: any burden on ISC must serve legitimate local interest (effects on ISC must be incidental) in order to be constitutional: --(A) If facially discriminatory strict scrutiny: must be no less restrictive alternative available; strong presumption of invalidity. --(B) If NOT facially discriminatory balancing test: uphold statute unless burden on ISC is clearly excessive in relation to local benefit. --(C) Court sometimes employs strict scrutiny when it suspects a discriminatory purpose behind statute. --(D) Does law generate negative externalities for other states (Philadelphia, Kassel)? This can weigh in balancing test or cause to fail SS. ---Ct. likely to find discrimination where: (1) effectively excludes virtually all out-of-staters from particular state market, but not if just one group of OOS (Exxon, Clover Leaf Creamery); (2) imposes costs on OOS that in-staters don’t bear (Hunt); (3) Apparently motivated by protectionist purpose (Hunt, Healy). -Philadelphia v. New Jersey: statute prohibiting importation of out-of-state waste facially/effectively disc. Not quarantine law, so no other purpose. -City of Clarkstown v. Carbone: city subsidized private waste station & guaranteed all flow to it. Not typical geographical discrimination but btwn that and all others— facial disc. Applied strict scrutiny, struck down. -Maine v. Taylor: even though facially disc., restriction on importation of live baitfish survives strict scrutiny b/c environmental concern (preservation of ecosystem) and no less burdensome way to sift through species. Deference here b/c court recognized they are not marine biologists. -Hunt v. WA State Apple Adv. Comm.: Court found effective d. in requiring out-of-state actors to use inferior grading system, and that less d. alternatives available (SS). Possibly court contemplated d. purpose in admission it was passed on behalf of NC apple industry. Inference: disc. effect disc. purpose? -Minnesota v. Clover Leaf Creamery: (particular industry) disposable pulpwood but not plastic containers allowed for milk; MN had pulpwood industry but not plastic. Environmentalism ostensive purpose but pulpwood worse for environment. Yet court upholds! Vs Hunt: (a) meaningful domestic resistance to statute; (b) prohibited sale vs. making OOS more costly, so less reason to suspect purpose. Vs. Carbone: will still be out-of-state pulpwood mnfg. competition. -West Lynn Creamery v. Healy: OOS dairy farmers taxed for health & safety inspection and proceeds pooled to be redistributed to in-state dairy producers. Health & safety inspections and dairy subsidies okay by themselves, but are protectionist in this combination by transferring funds from OOS to in-state. -Exxon Corp. v. Governor of Maryland: MD statute provided producer/refiner of petrol could not operate retail stations w/in state—practical effect: only OOS actors barred b/c no such in-state cos. No discrimination—no barrier to flow of interstate product. Blackmun’s Dissent: burden on retail services entering state. Response: structure/methods of operation in retail market (e.g. vertical integration) not protected by CC. -Kassel v. Consolidated Freightways Corp.: (non-classic protectionism) IA statute prohibited use of larger trucks; ostensive safety reasons; court struck down even though applies equally to in-state and OOS actors. New protectionism: IA making other states bear burdens of ISC wear from trucking and likelihood of increased accidents. Less deference to legislature—possibly infers disc. purpose from effect of deterring OOS trucks. Preemption: limitation on power of states. Sources: (1) Art. I § 10: restrictions on state power. (2) Art. VI: Supremacy clause. Note: absent preemption, can challenge state laws via either dormant CC or P&I clause. Policy considerations: should court preserve federalism or show deference to state/local legislatures? See policy re: dormant CC! -3 types: (1) Express: statute contains provision specifically indicating which state laws preempted. (2) Field: scheme of fed. regs. so pervasive as to reasonably evince intent of Congress to leave no room for states to supplement (like dormant CC). (3) Conflict: Either (a) compliance w/ both state and fed. law impossible or (b) state law presents obstacle to accomplishment/execution of federal purposes/objectives. -Gade v. NSMWA: invalidated Illinois reqs. for workers in addition to fed. OSHA reqs. Majority: field preemption intended to subject employees to only one set of regs. Concurrence: express preemption even though no conflict btwn two regs. Note: ct. can avoid preemption by narrowly construing purpose of fed. law! -Crosby v. Nat’l Foreign Trade Council: Cong. statute imposing mandatory/cond. sanctions on Burma 3 mos after similar Mass. statute. Ct. could have found field (“comprehensive”) but found conflict instead. State law is obstacle: (1) Impairs scope of prez power—less than full weight of nat’l economy at disposal; interferes w/ prez speaking as one voice in foreign affairs. Cf: Jackson in Youngstown: exec. authority greatest where express Cong. mandate. (2) Scope of Mass. law vs. fed.—MA statute less flexible (sanctions permit less) than fed., has no meaningful waivers, and covers foreign persons—what fed. law doesn’t prohibit it intends to permit. Weaker arg. if possible to comply with both statutes. Cong. awareness of MA law + silence =!=> non-preemption. State Actor Requirement: To what extent do Reconstruction Amendments empower fed. gov’t to regulate conduct of private individuals? A.13 always read as affecting private conduct (slavery prohibited anywhere in US, only private actors had slaves). Theory: Classic liberal conception—threats to freedom of ind. comes from gov’t; but Marsh v. Alabama (co. owned town, arrested JWs) private power just as dangerous; public function doctrine: private actors may be deemed state ones where many public functions delegated to them (limited—e.g. private schools not covered). Questionable distinctions: public/private, action/inaction. Analytically, can conceptualize any private infringement of const. values as result of gov’t inaction—e.g. gov’t denies equal protection if permits private racial disc. -Other justifications: (1) preserves zone of private autonomy, but sacrifices indiv. freedom via allowing violation of rights; (2) enhances federalism—preserves zone of state sovereignty (reg. of individuals province of state police power); questionable view of federalism post-civil rights and doesn’t justify rights infringing. -Requirements: for const. provision to implicate private conduct, must be either (A) sufficient degree of state involvement w/ that conduct or (B) failure by state to act in circ. where Const. affirmatively requires action (e.g. abolition of “badges & incidents” of slavery). Action/inaction distinction is unhelpful. -The Civil Rights Cases: (1883) Cong. cannot prohibit disc. in public facilities via “badges & incidents” provision—special legal status to former slaves (stupid case) -DeShaney v. W.C. Dep’t of Social Services: DP cl. does NOT require state to protect life/liberty/property against invasion by private actors. Abused child, state failed to stop dad from beating. Different outcome if e.g. state intervened for white but not black children (equal protection violation). -Flagg Brothers v. Brooks: Bank’s agents repossessed house pursuant to law—not state action so no need for procedural DP. Deprivation must be (1) Caused by state AND (2) by “fairly said” to be state actor—employed by OR acting w/ “significant aid” of state. Crucial: state embodied its decision to refrain from acting in statute. Argument against: FBs actions efficacious only b/c backed up by threat of state force—so satisfies (A). ***[Would balancing test be preferable?] -Lugar v. Edmondson Oil Co.: DP violation where writ of attachment for property executed by county sheriff sufficient state involvement (this & Shelly vs. FB). -Shelley v. Kraemer: No restrictive covenants b/c enforcement of them by courts constituted state action susceptible to A.14. Is this just b/c it is enforcement of racial restrictions against background of prohibition of restraints on alienability (i.e. racist governmental purpose)? Implicitly limited, e.g. can enforce trespass claims by racist owner! Washington v. Davis: Do facially neutral statutes w/ discriminatory impact (vs. intentionally disc. ones) constitute state action? Privileges & Immunities Clause: 2 clauses—A.14’s is distinguished from Art. IV’s in Slaughterhouse Cases: Ct. found Louisiana slaughterhouse monopoly preventing other butchers from having own business (had to pay to have animals slaughter there) constitutional, b/c P&I clause not incorporated (and doesn’t incorporate Bill of Rights). -Art. IV § 2: “P&I of Citizens in the several States”—sole purpose was to declare to several states that whatever rights are granted to own citizens must be rights of citizens of other states in your jurisdiction, the “Rights of Englishmen.” Protects fundamental rights e.g. to be free from torture. -14th Amendment: “P&I of citizens of the United States “—Ct. construes as response to Dred Scott to undo slavery and its effects; applies only to fed. gov’t, not states. Protects rights uniquely federal in character from “Fed. gov’t, its national character, Const., or its laws”—right to come to seat of gov’t and assert claim, seek its protection, share offices, access seaports, courts, habeas corpus, peaceably assemble. -Problems: (1) Practical nullity—guts A.14 P&I cl. b/c only protects rights in fed. law not much use to former slaves trying to get equality (2) Inconsistent with intent of Reconstruction Congress in adopting A.14—change from “several states” to “US” to make clear that slavery, fed. regulated, was abolished. -Alternative Readings: (1) Intended to incorporate Bill of Rights against states; but this would mean inclusion of a DP cl. was redundant, and original P&I cl. was distinct from BoR. (2) Meant to enforce remedial provisions of 1866 Civil Rights Act to remedy racial inequality (3) ***Meant to integrate P&I clause as limiting legis., DP against judiciary, and EP against executive—a natural reading rejected by court. Would infringe on federalism, but good arg. that this is exactly what RCong. had in mind—to prevent states from discriminating! -Solution: Ct. employed substantive due process (Lochner overruled Slaughterhouse), commerce clause, & A.14 § 5 enforcement powers for same result. Incorporation: whether/what extent Bill of Rights applied against states via A.14 due process clause. Fundamental fairness vs. total incorporation. -Barron v. Baltimore: (1833) A.5 “just compensation” provision applies only to fed. gov’t—states can take land whenever they want. -Twining v. NJ & Palko v. Connecticut: (1908, 1937) (fundamental fairness approach [Frankfurter]) due process clause incorporated only to the extent necessary to protect “fundamental principles of liberty and justice” which lie at base of all our civil/political institutions—i.e. that are essential to any concept of ordered liberty. These rights exist ind. of gov’ts and legislatures. Includes freedom of speech, press, assembly, religion, right to counsel; NOT A.5 right to freedom from self-incrimination or A.7 right to trial by jury. Problems: (1) Leaves too much to judicial discretion—can enforce/not enforce whatever rights they personally prefer. Examples: Dred Scott, DP clause protecting slaves as property; Lochner, DP clause protecting capital from gov’t intervention in its exploitation). Constraints proposed to deal w/ this problem: original intent, deference to state courts/legislatures regarding statute or judgment dealt with; look t moral judgments made on issue from other “Anglo-American” traditions—originalism cuts this off after American independence. (2) Should Const. interp. presume that fundamental fairness principles evolve or that they stay static? Who decides? -Adamson v. California: Black’s dissent contains theory of total incorporation: entire Bill of Rights is applied against the states. -Which is more protective of individual rights? While TI is more predictable and minimizes problem of judicial discretion, FF allows extension beyond BoR (e.g. abortion/contraceptives via fundamental right to privacy). -Duncan v. Louisiana: synthesis of TI and FF; hybrid approach: selective incorporation of BoR (except 2nd, 3rd, 7th right to jury trial in civil cases) but also additional fundamental rights e.g. privacy. -New vs. old FF test (Twining vs. Duncan): positive vs. negative framing, “unimaginable w/o” vs. “fundamentality,” hypothetical vs. actual.