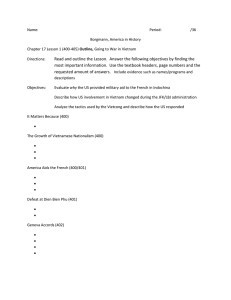

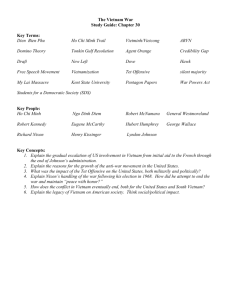

The Cold War US Involvement in Vietnam 1946 - 1975

advertisement

The Cold War US Involvement in Vietnam 1946 - 1975 US Involvement in Vietnam US involvement began during the closing days of World War II when the first US casualty, Lt. Col. A. Peter Dewey was killed on 26 September 1945. US involvement in Vietnam spanned six presidential administrations over a thirty year period. By 30 April 1975 when the US completed its withdrawal the US had suffered 58,209 KIA and more than 2,000 MIA. Roots of US Involvement Truman Administration: 1945 to 1953 Refused to recognize Ho’s government Ignored communications from Ho Reluctantly agreed to French reconquest Financially supported French efforts Accused of “losing” China, did not want to “lose” Vietnam Roots of US Involvement With the fall of Dien Bien Phu in May 1954 the French were forced out of Vietnam in July. Realizing they could not sustain their colonies in Indochina the French petitioned for peace. The resulting peace conference reflected the mounting tensions of the Cold War and the recent armistice ending the conflict in Korea. Roots of US Involvement The victorious Viet Minh, acceding to pressure from the USSR and communist China, agreed to a interim division along the 17th parallel. The Soviets and the Chinese feared a strained and confrontational peace agreement would further anger France and, more importantly, France’s ally the United States. The Communists also believed they were in a better position politically and felt they could resolve the situation in Vietnam by political action. Roots of US Involvement The Geneva Accords Vietnam would hold national elections in July 1956 to reunify the country The division at the seventeenth parallel would vanish with the elections Opposing forces (the Viet Minh and former Vietnamese troops who supported the French) were to withdraw to their respective sections Roots of US Involvement Eisenhower Administration: 1953 to 1961 Refused to sign Geneva Accords Violated the spirit of the accords Installed Diem as president of RVN Replaced France as Diem’s primary supporter Articulated the “Domino Theory” Sent about 750 military advisors to train army of RVN Roots of US Involvement With Vietnam split into the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (the north) and the State of Vietnam (the south) which ultimately became the Republic of Vietnam (aka the Republic of South Vietnam) northern leadership moved to oust the US backed government in the south headed by Ngo Dinh Diem. Roots of US Involvement President Ngo Dinh Diem had no intention of holding elections for a united Vietnam and as his regime became more unpopular his political opponents began to consider alternatives. They eventually came to believe violence was the only way to persuade Diem to agree to the terms of the 1954 Geneva Conference. From 1956 to 1957 the south experienced a huge increase in the number of peasants leaving their homes to join armed insurgent groups in the back areas of Vietnam. The insurgents could not take on the South Vietnamese Army at first so they concentrated on 'soft targets'. In 1959, an estimated 1,200 of Diem's government officials were murdered. Roots of US Involvement 1959 At first the leader of North Vietnam opposed the terrorism but changed his mind when he was informed the attacks had been so successful that if the north did not support the insurgents unified Vietnam was out of the question. North Vietnam’s Central Executive Committee issues Resolution 15, changing its strategy toward South Vietnam from "political struggle" to "armed struggle." The North Vietnamese Army creates Group 559: the specialized group is given the mission of establishing a supply route from the north to rebel forces in the south. Prince Sihanouk of Cambodia allows Group 559 to develop the route along the Vietnamese/Cambodian border, with branches spreading into Vietnam along its entire length. This route becomes known as the Ho Chi Minh Trail. The Ho Chi Minh Trail Roots of US Involvement 1960 In 1960 Ho Chi Minh persuaded the various insurgent groups to form a more powerful and effective resistance organization. In December, 1960, insurgents formed the National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam (NLF). The NLF, or the 'Vietcong', as the Americans were to call them, was a conglomeration of more then a dozen different political and religious groups. The leader of the NLF, Hua Tho, was a non-Marxist, Saigon lawyer, but large numbers of the movement supported communism. The NLF fell more and more under the control of Ho Chi Minh and North Vietnam. Roots of US Involvement Kennedy Administration: 1961 to 1963 Rejected negotiated settlement with Ho Refused recommendations to dramatically increase U.S. military presence but did increase the number of advisors to about 16,000 by 1963 Encouraged coup that deposed & assassinated Diem Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) In 1957 the US Military Assistance Advisor Group (MAAG) assumed responsibility for training South Vietnamese forces. Republic of Vietnam Navy Vietnamese Marines Ap Bac – The First Invasion January 2, 1963 350 Vietcong inflict 191 casualties on a combined ARVN/US (advisors & transport) assault force of 1400 while suffering but 57. More serious was the timidity and utter unwillingness of the South Vietnamese to engage the enemy or to advance under fire even to aid fellow ARVN’s. "These people (the Vietnamese) won't listen—they make the same mistakes over and over again in the same way." The Buddhist Crisis In the days just previous to the Buddhist celebration of Vesak – the birthday of Gautama Buddha – Vatican flags had been flown in association with a Catholic celebration. Following the Catholic celebrations, Diem came to the conclusion that the government ought to enforce a longstanding though seldom enforced law prohibiting the flying of ALL religious flags outdoors. The flying of flags represented an assertion of power to the Vietnamese and Diem – in all likelihood – enforced the law in order to preserve the government’s prestige. (Moyar, Mark. Triumph Forsaken. p. 212) The Buddhist Crisis The ordinance applied to ALL religious groups but the timing of the decision to enforce the decree was ill advised at best. On 07 May 1963 at the urging of several Buddhist monks, thousands of Buddhist flags were flown publically and the next day 500 Buddhists protesters gathered at a pagoda in Hue with banners protesting the ban of the public display of their flags. The Buddhist Crisis The protesters were led by Tri Quang who told the crowd the government favored the Catholics and persecuted Buddhists. When Tri Quang attempted to broadcast a tape critical of the government the local radio station’s director refused to permit the broadcast. When the provincial chief arrived he attempted to convince the protesters to go home but they refused and scuffling followed by rock throwing and eventually the use of fire hoses to break up the protesters was employed. When the army arrived and the protesters continued to refuse to leave, artillery blanks and rifles were fired into the air. According to Buddhists the Army then opened fire on the protesters and threw grenades into the crowd. While some protesters were in all likelihood injured by government troops it is also probable that some of the protesters were injured when the protesters themselves set of explosives among the crowd. What is for certain is that 8 people died and 14 were injured, most of them Buddhist protesters. The Buddhist Crisis The government expressed sorrow for those that had been killed and promised the government would provide compensation to the families leading many, including the American consul in Hue to “Believe crisis nearing end.” Tri Quang and other leaders refused to be conciliated. They issued a new list of demands: responsible government officials had to be punished removal of all restrictions concerning the flying of flags a prohibition against the arrest of Buddhists The Buddhist Crisis Diem opened a dialogue with the Buddhists but refused – for obvious reasons – to give in to the Buddhist demands, especially the last. Diem did not round up and silence the Buddhists though the example coming from Ho Chi Minh in the north was for him to do exactly that. The US press corps in Saigon seized on this incident and began to use it as evidence that the Diem government lacked public support, was hopelessly repressive and therefore deserved to be overthrown. The Buddhist Crisis The two main sources of information used by the US press were Pham Ngoc Thao and Pham Xuan An Pham Ngoc Thao was a colonel in the South Vietnamese Army. Pham Xuan An was a member of the press corps serving Reuters as a stringer. Both were communist spies. The Buddhist Crisis Thieh Quang Duc – June 11, 1963 Concerning the supposed Diem persecution and repression of the Buddhists: 1,275 Buddhist pagodas were built under the Diem administration The Diem administration provided large amounts of money for Buddhists schools, ceremonies and other activities. Of Diem’s 18 cabinet members 5 were Catholic, 5 were Confucians, and 8 were Buddhists. 12 Provincial chiefs were Catholic while 26 were either Buddhists or Confucians. Only three of the top military officers were Catholic. The Great Myth Population The US press consistently claimed that 70% to 80% of the South Vietnamese population was Buddhist. A large portion of the population did have some type of Buddhist affiliation – HOWEVER: only 3 to 4 million of 15 million South Vietnamese were Buddhists and only 50% of those were actual practicing Buddhists most Buddhists lived in the countryside and knew nothing of political disturbances Confucians numbered about 3 to 4 million also 1 ½ million were Catholics Another 2 ½ to 3 million were either Cao Dai or Hoa Hao The remainder were animists, Taoists, Protestant Christians, Hindus or Muslims. Initial Involvement and Escalation Johnson Administration (1963 – 1968) Wanted to avoid provoking wider war Followed a policy of gradual escalation Hoped DRV would eventually quit Dramatically increased U.S. involvement Troop strength peaked at ~500,000 in 1968 Initiated peace talks with DRV in 1968 Initial US Involvement August 2 & 4, 1964 DD 731 – USS Maddox DD 951 – USS Turner C. Joy Initial Involvement On 11 October 1964 the Central Military Commission and the High Command of theVietnamese People’s Army ordered the communist forces operating in the south to initiate three offensives during the winter and spring 1965. Eastern Nam Bo Central Trung Bo Tay Nguyen (Central Highlands) Initial Involvement 1965 February 07 – Viet Cong attack the military barracks at Pleiku: the early morning attack leaves 8 Americans dead and 108 wounded – several US aircraft are damaged or destroyed President Johnson takes the attack personally and orders air strikes that will become Operation Rolling Thunder. The operation will bomb targets in North Vietnam over the next three years. March 08 – Two battalions of US Marines land at Da Nang – their primary mission is to provide security for the US airbase Aug – Marines conduct first offensive operations against VC south of Chu Lai Nov – US Army engages NVA regulars in the Ia Drang Valley Dec – US troops strength reaches 200,000 Initial Involvement Escalation Initial Involvement Escalation 8 March 64 – two battalions of Marines land at Danang to provide security or the US air base 30 June 65 – The Marines have some seven battalions in Military Region 1 – I Corps. The Marines establish bases at Phu Bai, and Chu Lai north and south of Danang. The Second Invasion - 1965 In early August the Marine commander at Chu Lai learned of a planned VC attack. Instead of waiting for the VC to strike General Lew Walt directed a pre-emptive attack. Operation Starlight lasted 6 days and involved both US Marines and ARVN troops defeating the 1st VC Regiment. The US/ARVN troops claimed 29 KIA and another 70 WIA while inflicting 281 KIA on the VC Regiment reflecting the popular idea of “body count” during this phase of the war. In November, following another attack in the Pleiku area the US 7th Cavalry conducted operations in the Ia Drang valley against North Vietnamese Regulars – this proved to be the initial “invasion by NVA regulars. Escalation US Goals in Vietnam Limited war, didn’t want to provoke: Soviet Union (USSR) People’s Republic of China (PRC) A stable, non-communist government in South Vietnam (RVN) Hoped to “Get in, get out, get on” Early Opposition Gaylord Nelson (D-Wis) - Questioned the unlimited nature of the wording of the resolution as it applied to presidential power concerning both troop strength/deployment and military response including a “direct military assault.” J. William Fulbright (D-Ark) – Read the resolution to the Senate but during the debate that followed said he would deplore the deployment of large number of US troops William Gruening (D-Alk) – Disagreed with the presidents policy. Questioned the limits (or lack of limits) on presidential powers under the resolution. “I am opposed to sacrificing a single American boy in this venture.” Wayne Morse (D-Ore.) –” I believe that history will record that we have made a great mistake. . . I believe this resolution to be a historic mistake. I believe that within the next century, future generations will look with dismay and great disappointment upon a Congress which is now about to make such a historic mistake. M ay -6 Ju 5 l-6 Se 5 pN 65 ov -6 Ja 5 nM 66 ar M 66 ay -6 6 Ju l-6 Se 6 p6 N 6 ov -6 Ja 6 nM 67 ar M 67 ay -6 7 Ju l-6 Se 7 p6 N 7 ov -6 Ja 7 nM 68 ar M 68 ay -6 Ju 8 l-6 Se 8 pN 68 ov -6 Ja 8 nM 69 ar M 69 ay -6 Ju 9 l-6 Se 9 pN 69 ov -6 Ja 9 nM 70 ar M 70 ay -7 Ju 0 l-7 Se 0 pN 70 ov -7 Ja 0 nM 71 ar M 71 ay -7 1 Declining Public Support 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 Progress Reports In November of 1967, the Administration launched an extensive "public relations" campaign. It was designed to convince Congress, the press, and the public that there was "progress" in Vietnam and that the war was being "won.“ Johnson was advised to "[E]mphasize light at the end of the tunnel instead of battles, deaths, and danger." "There are ways," Johnson was told, "of guiding the press to show light at the end of the tunnel“ To head this effort, Johnson brought General William Westmoreland, commander of American forces in Vietnam, to Washington. Westmoreland addressed the National Press Club saying that the U.S. had reached the point "where the end comes into view" Turning Point: 1968 Just after midnight on 31 January 1968 the North Vietnamese launched the Tet Mau Than (Tet) offensive in Nha Trang The primary objectives of this offensive, as with all offensives launched by Hanoi, were political. The North Vietnamese were well acquainted with the US political process and for two years had been preparing this offensive with the eventual goal of affecting the 1968 Presidential Election. The offensive would also serve to show the world that the South Vietnamese people, when given the chance, would rally to the cause of the National Liberation Front (NLF) and the Viet Cong (VC). Turning Point: 1968 By the end of the offensive the world “knew” that the RVNAF were defeated at every juncture. It was a broken force and the government in the South was ready for conquest because it was about to disintegrate The American media had a field day. Every night pictures of dead US service men streamed across television sets. It was implied that the VC had captured the US Embassy in Saigon (they had not). 27 February 1968 Walter Cronkite delivered his famous broadcast for CBS in which he said “We are mired in stalemate.” To make matters worse, President Johnson and his staff were watching Cronkite’s broadcast and began to second guess themselves. Turning Point: 1968 The chief of the Saigon police executing a suspected Viet Cong Turning Point: 1968 Unfortunately, the “world” if not flat out wrong was at least incorrect in its perceptions. The South Vietnamese people did not rally to the north. The guerrilla movement was exposed and its infrastructure decimated. The VC were devastated. While actual looses may never be known, between 50,000 and 80,000 communists were killed. Two-thirds of those were VC casualties. The VC lost its prime source of leadership. Turning Point: 1968 On St. Patrick’s Day, March 17, 1968, Wallace Carroll, an anti-war newspaper columnist, wrote and published a signed column titled “Vietnam – Quo Vidas?” In it he contended that America was “misguided” and that the war was “irrelevant to the goal of thwarting Soviet expansion.” Dean Acheson, a former Secretary of State, and an advisor to President Kennedy showed the article to President Johnson. The Washington Post would later report that this column had a huge impact on Johnson’s decision not to seek re-election Turning Point: 1968 Webb summed up the outcome of the offensive when he wrote that the offensive was the, “… watershed event of the war from the American perspective, since public support fell steadily from that point forward. Nonetheless, Tet 1968 was a clear military victory. American and South Vietnamese forces at a cost of 4,000 and 5,000 lives respectively, killed 58,000 enemy soldiers, turned back the communists at every point, and effectively destroyed the South Vietnamese communist military (NLF). In Vietnamese terms Tet 1968 was a political victory as well. Contrary to the predictions of General Giap and others, the South Vietnamese people declined to support the communists who temporarily gained control of their towns and villages.” The 1968 Election <= Richard M. Nixon Republican Hubert H. Humphrey => Democrat George W. Wallace => American Independent party Democratic National Convention Chicago 1968 The 1968 Election The Candidates’ proposals for Vietnam Nixon: “Secret plan” to end the war Humphrey: Suspend bombing as an act of good faith, continue negotiations Wallace: Expand war, use nuclear weapons to defeat North Vietnam Trying to Disengage Nixon Administration (1968 – 1973) Claimed to have a “secret plan” to end the war Promised “peace with honor” Expanded air war to Laos & Cambodia Invaded Cambodia & Laos Negotiated Paris Peace Accords Withdrew last U.S. troops in 1973 My Lai Massacre March 16, 1968 Changing Commanders Creighton Adams took command of US forces in June 1968 and with the change in command came a change in the way the US armed forces approached the war. There was an immediate shift in: the concept of the nature and conduct of the war the appropriate measures of merit the tactics to be applied The Cambodian Incursion (May – June 1970) Attempt to cut Ho Chi Minh Trail Destroy PAVN, NLF forces in SE Cambodia Destroy communist base areas & sanctuaries Provoked massive unrest in U.S. universities Kent State University May 4, 1970 1972 For four years neither the NVA, the NLA or the VC could mount a major offensive. Tet 68 had more than decimated each. Hanoi decided to put all its hopes and dreams into one massive offensive. Always aware of the political environment and election cycles in the US, they determined to launch their Nguyen-Hue Offensive in the spring of 1972. Both the timing and the naming of the offensive were geared toward recalling Vietnamese nationalism once again. The Nguyen-Hue Offensive was planned on three separate “fronts.” 1. An assault would attack into Military Region (MR) 1 or I Corps. 2. Another point of attack would be the central highlands of MR II into Kontum Province with the provincial capital of Kontum city as an objective. 3. Finally, in MR III and IV drives would be made to surround and isolate Saigon the capital of South Vietnam. Truong, Ngo Quang. The Easter Offensive of 1972. Washington: U.S. Army Center of Military History, 1980. p. 9. 1972 Offensive Assault on Military Region I The Christmas Bombings (1972) Paris Peace Accords January 27, 1973 General cease-fire All U.S. troops out in 60 days DRV to release all U.S. POWs Neither side to send further troops to RVN (150,000 PAVN troops allowed to remain) Created national Council of Reconciliation Reconciliation to be Gradual Peaceful Free of coercion In January, 1973 the “Agreement on Ending the War and Restoring Peace in Vietnam” more informally know as the Paris accord was signed. Shortly thereafter the United States Congress voted to withdraw funding from the South Vietnamese. With no money to buy bullets, beans or gas, the defensive capabilities of the RVNAF eroded and eventually collapsed. On April 29, 1975 the last Americans who wished departed Saigon, South Vietnam. The next day, the South Vietnamese government surrendered. The North had finally won a campaign in the South. Operation Frequent Wind The End Thousands upon thousands of our Allies were tortured and died in communist "Re-education Camps" after the fall of the South on April 30, 1975. Multitudes of others have been scarred for life. During five trips back to Vietnam in the 1990's one Vietnam veteran found that most of the former soldiers that he encountered still welcome the American veteran back with open arms. As strange as it may seem, the camaraderie of a shared experience is what continues to bind veterans together. Many former Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Army soldiers who are still trying to come to terms with the war. One retired Viet Cong colonel said that, if he had to do it all over again, he would join the fight against the North. For his years of servitude to the communist regime all he has to show for it is a $5 a month retirement check. There are no other benefits to living under communist rule. Assessing of the War Sapped national will Fragmented national consensus that had dominated foreign policy since 1947 Failed to transfer democracy to Vietnam Eroded respect for the military Drastically divided the U.S. population Eroded trust and confidence between the American people and their government The End ~ We Joined their Dream ~ We Fought Side by Side ~ We Deserted Them ~

![vietnam[1].](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/005329784_1-42b2e9fc4f7c73463c31fd4de82c4fa3-300x300.png)