Theory of Forager Networks: Simulation, Comparative Data and

advertisement

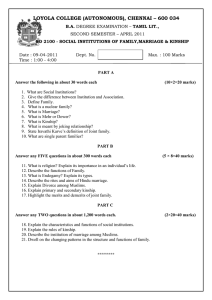

Theory of Forager Networks: Simulation, Comparative Data and Evolution of Human Cohesion and Cooperation IMBS Colloquium October 9 2012 Doug White, partial collaboration with Tolga Oztan SFI Causality Working Group Irvine Social Science Gateway (SDSC) (DE R software, Dow & Eff; capability of merging datasets, imputing missing data, applying autocorrelation controls and applying MCMC Bayes Factors) Predictive Cohesion Theory (previous NSF) Kinsources, Project Simpa (French NSF) Theory of Forager Networks: Simulation, Comparative Data and Evolution of Human Cohesion and Cooperation **double starred slides begin new topics • 4-6 Cohesion, cycles & cooperative ties in network structures • 7-14 Kinship history, networks and the bicomponent (!Kung) • 15-26 Evolution of cooperation, network density & kin behavior: Joking, Avoidances and a density packing threshold • 27-31 4 Simulations: Boorman/Levitt 1980 to Helbing 2012 • 32 Succinct Summary for forager evolution • 33-34 Beyond foragers: the Densification of human society and what we know about egalitarian behavior and network bullying in schools • 36 Current Kinship Debate in Anthropology **Moody and White 2003 structural cohesion as a measurement concept Idea: implement Menger’s 1927 theorem as a pair of isomorphic measurements: Maximal subnetwork with no less than a (min) k-node separator (easy proof) min here = max below Maximal k-cohesive subnetwork with a minimum number k of node-independent paths between any x, y pairs of nodes (hard) isomorphic with above http://www.math.unm.edu/~loring/links/graph_s05/Menger.pdf proof Theorem proven in 2005 by Ron Aharoni for infinite graphs http://www.math.haifa.ac.il/berger/menger_2nd_submition.pdf Hard part to develop an algorithm (slow – now fast computation) 3 3 Cohesion: History • The 1927 Menger theorem proves the equivalence of a largest k-connected set of nodes in a network (with k or more node-independent paths between them, none with a common intermediary) and a a largest k-separable set of nodes in the same network that cannot be separated without removal of at least k nodes. (Similarly for pairs of nodes.) Synonyms today are kcohesive sets (or pairs) or stru-cohesion. This is considered one of the core theorems and insights of GT (graph theory) • “Structural cohesion” still defined after 1927 by a laundry list, not GT. • The 2001 White-Harary article proves that GT gives a useful measure of cohesive subgroups in networks. The algorithm for stru-cohesion is thought to be NP hard. The 2003 Moody-White article implemented an algorithm in SAS computing stru-cohesion. It showed that for 10 randomly chosen AddHealth high school studies of friendship networks stru-coheion (kconnectivity outperforms all other network measures tested for prediction of student questionnaire responses measuring “attachment to school.” Stru-coehison is a major predictor in the Powell, White, Koput & Owen-Smith (2005) study of the Biotech Industry. Predictions of key properties of subgroups of kinship networks hypothesized to be more demonstrably cohesive and “cooperative” have since been found to yield significant results (100,000 marriage networks in Medieval Florence 1200-1500, Turkish Nomads, farming communities in Austria and Costa Rica, etc.). The computationally hard 2003 MW algorithm is programmed by iGraph's Csárdi in 2009. iGraph’s Csárdi 2012 discovers an O(<n2) cohesive.blocking algorithm. (Tolga Oztan) 4 Kinship Data as a DAG (Dir Asym Graph): Basic kin-net kinship networks: Nodes are parents, edges are gendered individuals Married individuals are a single node but link up to separate parents Kin-net graphs constructed from standard genealogies or GED files, using PAJEK or a number of other programs. Femal e edge Male edge This type of graph allows us to study cohesion in kinship networks. It has no k-components with k > 2, hierarchically embedded Marries her MBS Coefficients of biological relatedness ri,j and pairwise cohesion ki,j can be coded in matrices or graphs with individuals as edges FaFaSiDaSo 5 Some Forager Datasets (Oztan) • !Kin These and 21 others examined as well in their demographicenvironmental and network contexts. All but two have Joking and/or Avoidance relatives. Joking is cooperative; Avoidance reduces conflict. 6 **Kinship: History, Networks, Cohesion Evolutionary (Galton* contra:Tylor; Driver*) Processual & Genealogy* (Rivers*) Structure & Link Behavior* (Radcliffe-Brown*) Functional (Malinowski, Murdock*) Structural-Algebraic (Lévi-Strauss*, Weil*) Critical (Schneider* Kinship not simply biological) Empirical Formalism-Cognition (Read*, Leaf*) Networks (Graph theoretic, Link behavior, Network cohesion, Bicomponents-- White*, Harary, Houseman*, Hamberger*, Oztan*) Statistics (Bayes) 7 Hypothesis: bicomponent (yellow) nodes are more likely “cooperators” (among the questions being explored by Oztan for his PhD) 8 !Kung band-wise kinship p-graph solid lines male, dashed lines female, arrows point to parents (Oztan) Research questions, e.g.: How do usufruct rights in resource clusters map onto kin ties, marriage and movement between groups, and band memberships? 9 Basic kinship networks are bicomponents with egalitarian structure (conducive to low bullying). Incoming-arrow to parents, outgoing from children, dotted line for daughter to parents, solid lines son to parents No tri- or higher k-component: !Kung san (Kalahari desert) Degree centralities are also distributed: 10 Using graph theory cycles to measure cohesion between sides as a possible predictor of cooperation in a foraging society (!Kung – result is similar if females form the sides, men the links) e – n + 1 = No. of cycles 128 – 118 + 1 = only 11! - 5/11 are not sided, probability=n.s. Tho this looks like two-sided marriages sides are random. For these (!Kung) foragers Within generations its joking relatives across-sides that generate dyadic 11 cooperation This is the band-level pattern of !Kung Marriages (crosssided = Joking and Avoidances) !Kung Marriages have too little density of offspring to form many cohesive cycles 12 Pul Eliyan Sidedness (P-graph) in-laws are cooperative, siblings competitive over inheritance of land and irrigation resources passed to son or daughter; gender ambiguity in sides. This is not random; 146-103+1=44 cycles with 8 “errors” (p=.002). But this network is almost perfectly 2-sided for marriages of those with common ancestors (this can be seen visually). (Foragers are not dense enough to have this level of cohesive sidedness) Can you spot the “wrong marriage”? Sidedness cohesion entails cooperation because brothers-in-law cooperate and Joke: 77 red lines within generations for cooperative ties 13 between sides But !Kung Joking and Avoidances and local “sides” are ordered purely by the ego role-pattern ego 14 **Evolution of Cooperation: History • Evolutionary (Tylor 1889 faulty assumptions) • Processual (Rivers'09) • Inclusive fitness (Hamilton'64) • Kin selection (Trivers'71) • Clustered spatial selection (Boorman & Levitt'80) • Reputation and indirect reciprocity (Alexander'87) • Nowak (2006, 2011, 2012) • Network cohesion and kin-type network cohesion 15 Kinship, Cohesion, and the Evolution of Human Cooperation • You might wonder why these titles: what has kinship to do with cohesion and with early human cooperation? • to find out we visit some network structures, forager behavior and simulations. 16 Forager Cooperation 1: Binford 2001 Lewis Binford showed that for recent forager groups, as for Pleistocene archaeological findings, environmental variables are the primary shapers of variation in social and ethnographic features. It is only at or above the packing threshold that the many various forms of social organizational complexity appear. Ethnographic surveys of foragers uniformly show, rather than dominance hierarchies, reverse dominance hierarchies, where persons who attempt to dominate others, or their groups, are punished by a variety of means that prevent domination, including killing or exclusion (Boehm 2012). Prestigious leaders emerge out of generosity and trust. In a game-theoretic framework, it is reputation and indirect reciprocity, Nowak’s fourth mechanism (Alexander 1987), not his first (Prisoner's dilemma), that Boehm and Binford see as the engines of forager cooperation, alongside selection (which Boehm affirms, Binford denies). Foragers have no up-down cycles of cooperation and defection with a game-theoretic basis in the Prisoner’s Dilemma of a minimax optimum temptation to defect from a formerly cooperative partner, except under catastrophic environmental conditions. We will soon look at forager kinship behavior. 17 Forager Cooperation 2: Binford 2001 Binford identified “unpacked” foragers as people living below a threshold at which “residential group mobility is … a viable strategy for insuring subsistence security from naturally distributed food resources” (estimated at 9.1 persons per 100 km2). These migratory “nonpacked” foragers have self-similar patterns of behavior when comparing archaic and more contemporary time periods, i.e., as between archaeological findings and ethnographies written over the past 400 years. Claire Porter and Frank Marlowe note, “It is frequently suggested that human foragers occupy ‘marginal’ habitats that are poor for human subsistence because the more productive habitats they used to occupy have been taken over by more powerful agriculturalists. This would make ethnographically described foragers a biased sample of the foragers who existed before agriculture and thus poor analogs of earlier foragers.” Porter and Marlow tested that assertion “using global remote sensing data to estimate habitat productivity for a representative sample of societies worldwide, as well as a warm-climate subsample more relevant for earlier periods of human evolution.” Their results show that “foraging societies worldwide do not inhabit significantly more marginal habitats than agriculturalists” (White, Gosti, Oztan & Snarey). 18 Forager Cooperation 3: Cohesion Within the networks of nonpacked foragers cooperation is based on indirect reciprocity and easily emulated reputations. Children are taken by their family members to learn the skills of more distant kin. Differentiation is present and valued rather than competitive. Sharing among near and distant kin is everpresent. What is unique about human kinship is the absence of dominance hierarchies based on gender, compared to our closest relatives, Old World Apes (male dominance, transmitted to sons, who remain in the community while daughters migrate out) and New World monkeys (female dominance hierarchies, transmitted to daughters, who remain in the community, while sons migrate out to mate). Humans evolved to recognize mating pairs within the band or community, to recognize fathers and father’s kin as well as the kin of mothers. This forms a basis for social cohesion among human foragers that differs from other primates. It's not simply a matter of sharing. Eskimos share, for example, but sharing is also greater for some than for others (Pryor and Graburn 1980 “The Myth of Reciprocity”). Our hypothesis (White, Oztan) is that to the extent that differences in cohesion can be recognized and measured in forager societies, the more cohesive subgroups will also exhibit greater cooperation within the community. People are free to leave a community but those who leave are likely to be those with lower 19 cohesion. Here is another kind of network with Joking Relations (Cohesive) as the Cooperative Glue In the sample of 34 foragers the six groups with Br/Si Avoidance with the regressor “Fishing” as the predictor, p=.01. The Tenino are foraging traders at the gulf of the Columbia River. The other 5 foragers are also central in trading networks. 20 Like kinship Joking behaviors that create cooperation between Brothersin-law in the Pul Eliya or !Kung cases, Tenino brothers-in-law (WiBr/SiHu) form chains of trading partners with special privileges; e.g., borrowing property and returning something of lesser value. Chains of brothers-in-law operated the trading routes. WiBr's daughters is also a “Joking” relative and can pass intimate information; you can joke with his sons. These foragers were the major trading society at the mouth of the Columbia River. WiBrDa, Da of a trade partner WiBr, is “intimate but not sexually” with the FaSiHu trade partner. Between siblings-in-law of opposite sex—BrWi & SiHu, “Intimacy” occurs, even sexual intercourse. (Murdock 1965). Formal kintype expectations for Joking relatives generally promote cooperation. Brother and Sister reinforce this with an avoidance relation: they cannot even sit together or talk. WiBrWi is “like” a prohibited sister and also entails that Br/Si avoid each other. By avoiding WiBrWi there is no possibility of jealousy between WiBr and SiHu, the trade partners. The Br/Si → WiBrWi entailment (WBW more widespread than Br/Si) goes against a universal “extensionist” priority of the nuclear family (Murdock, Shapiro, etc.) 21 Forager Cooperation 4: Binford 2001 Binford (p.469): “Below the packing [settlement] threshold, hunter-gatherers are organized so that all participating individuals have maximal access to the [essential] vital resources that are accessible in their subsistence ranges. Participation in an economically integrated group means that all individuals endeavor to minimize the risk and maximize the return from cooperative labor that is directed toward obtaining the vital resources needed to sustain the group as a whole.” This statement about nonpacked hunter-gatherers does not imply that equal rights are assured by the society. “Rather, in their social world, trust and respect are built upon the lifelong associations and interactions of individual members.” Joking cooperativity fits here. “Persons who are not considered trustworthy or 'respectable' by the community may be denied not only equal access to resources but even their very right to exist, which is hardly compatible with the idea of an egalitarian society in which all individuals have rights to the corporately shared largesse." We learn from a social network viewpoint not only that “sharing is very common among hunter-gatherer groups that have not approached the packing threshold, as is the practice—when necessary—of using tools and supplies that belong to other persons,” but also that these are societies with “kin conventions extending food procurement rights to distant kinsmen,” rights that “tend to disappear” as mobility declines above the packing threshold. These networks persist intergenerationally, and relatively continuous cooperation was likely to have been part of the evolution of cooperation among nonpacked foragers. 22 A full dataset for 160 cases showing Avoidances (and some of the Joking data, both coded by Murdock) are at: http://intersci.ss.uci.edu/wiki/index.php/Kin_Avoidances http://intersci.ss.uci.edu/wiki/index.php/Kin_Avoidances#Data_a nd_Concept_Lattice Data on hunting, fishing, gathering, density etc. is found in Binford (2001:117-129) Constructing Frames of Reference: An Analytical Method for Archaeological Theory Building Using Hunter-Gatherer and Environmental Datasets (N=339) Merger of *.Rdata files is accomplished in the Irvine Social Science Gateway, linked to online training and courses. Note: As part of the Pleistocene comparability argument, Binford's “terrestrial” environmental model estimates carrying capacity for a non-cultural animal shaped like us, eating what we eat, helps to compare forager constraints archaeologically with the ethnographic present. 23 Table 1: population density & a packing threshold at 9 people/kmsq Differentially related to Joking relations and Avoidances (p=.008) Avoidances increase with density & lower hunting. Joking decreases with density & higher hunting. 3-way p=.008. 2-way between p=.01, .10 Density: Packing threshold at 11 people/kmsq at which there is no longer unoccupied space into which mobile hunter-gatherers could move (Binford 2001). 24 The packing density threshold (9.1 persons/sqkm) is a significant separator of Joking-Cooperation versus Avoidance-as Conflict reduction. It is a density value at which there is no longer unoccupied space into which a new members of minimal mobile hunter-gatherer group can be sustained (Binford 2001). All but two of our 34 forager groups have Joking or Avoidance or both. THIS IS PROBABLY AN INDICATOR THAT THESE PATTERNED AND OBLIGATORY KIN RELATIONSHIPS HAVE BEEN PRESENT IN PROTOTYPICAL FORAGER SOCIETIES. THERE IS NO REASON WHY THESE REGULATOR KIN BEHAVIORS SHOULD NOT HAVE BEEN COMMON IN THE LATE PALEOLITHIC, EVEN BEFORE THE ADVENT OF HUMAN LANGUAGES. They co-occur even below the packing threshold, but Joking, which creates cooperation, is more common, and declines above the threshold, as populations grow large. Avoidance, which avoids conflict, is also common, but tends to replace Joking as populations grow and kin relations grow thinner, with more potential for conflicts between non-kin. Presumably, these are prototypical integrative behavioral mechanisms for early cooperativity. Because certain Avoidances eliminate many of the Joking 25 relations, but not vice versa, Avoidances have precise Kin Avoidances 1995 DRW worldwide comparative result: kin avoidance entailments across kin types, drawn by Wille. Again: The Br/Si → WiBrWi entailment (WBW more widespread than Br/Si) goes against a universal “extentionist” priority of the nuclear family. These avoidance rules do hold for foragers above the packing threshold. 26 **Martin Nowak (2012) explains human cooperation with five alternative models 1 through a minimax game-theoretic model •Prisoner's dilemma 2 clustered spatial selection 3 kin selection 4 reputation and indirect reciprocity 5 group selection He claims that in every era, Humans have experienced up-down cycles of cooperation and competition. We question that assumption for Pleistocene foragers. We offer 4 different simulations 27 Simulations: What kinds of (kinship) networks do foragers have? © Helbing, Dirk. 2012. Social Self-Organization]. Springer Berlin. Chapter 14. Systemic Risks in Society and Economics] 285-299 Fig. 14.10 Establishment of cooperation in a world with local interactions and local mobility (left) in comparison with the breakdown of cooperation in a world with global interactions and global mobility (right) (blue square= cooperators, red = defectors/cheaters/free-riders) (after [p140]). The loss of solidarity results from a lack of neighborhood interactions, not from larger mobility. (see Boorman and Levitt 1980 Chs. 2-5. The Genetics of Altruism. NY: Academic Press) 28 Simulations: ©Helbing 2012 Social SelfOrganization. Springer Berlin. # (6) [http://www.springerlink.com/content/8u273nk752q31wj5/fulltext.html Cooperation in Social Dilemmas] 139-151. Summary: adaptive group pressure, which makes the payoffs to cooperation dependent on the endogeneous dynamics in the population. This could explain the extent of cooperation among foragers. # (7) [http://www.springerlink.com/content/u81821078n335152/fulltext.html Coevolution of Social Behavior and Spatial Organization] 153-167. Summary: the sudden outbreak of predominant cooperation in a noisy world dominated by selfishness and defection, when individuals imitate superior strategies and show success-driven migration. In our model, individuals are unrelated, and do not inherit behavioral traits. They defect or cooperate selfishly when the opportunity arises, and they do not know how often they will interact or have interacted with someone else. Moreover, our individuals have no reputation mechanism to form friendship networks…. the outbreak of prevailing cooperation, when directed motion is integrated in a game-theoretical model, is remarkable, particularly when random strategy mutations and random relocations challenge the formation and survival of cooperative clusters. Our results suggest that mobility is significant for the evolution of social order, and essential for its stabilization and maintenance. 29 Simulations: ©Helbing 2012 # (8) [http://www.springerlink.com/content/565020k868146593/fulltext.html Evolution of Moral Behavior] 169-184. Summary: considering spatial interactions with neighboring individuals, our model reveals several interesting effects: First, moralists can fully eliminate cooperators. This spreading of punishing behavior requires a segregation of behavioral strategies and solves the “second-order freerider problem”. Second, the system behavior changes its character significantly even after very long times (“who laughs last laughs best effect”). Third, the presence of a number of defectors can largely accelerate the victory of moralists over non-punishing cooperators. Fourth, in order to succeed, moralists may profit from immoralists in a way that appears like an “unholy collaboration”. Our findings suggest that the consideration of punishment strategies allows to understand the establishment and spreading of “moral behavior” by means of game-theoretical concepts. This demonstrates that quantitative biological modeling approaches are powerful even in domains that have been addressed with non-mathematical concepts so far. The complex dynamics of certain social behaviors becomes understandable as result of an evolutionary competition between different behavioral strategies. This could help explain the benefits among foragers of punishment of dominant “bullying” individuals whom might otherwise emerge as leaders. 30 Simulations: ©Helbing 2012 # (9) [http://www.springerlink.com/content/d78678k17634r921/fulltext.html Coordination and Competitive Innovation Spreading in Social Networks] 185-199. Summary: Recent studies of the competition between innovations have highlighted the influence of switching costs and interaction networks, but the problem is still puzzling. We introduce a novelmodel that reveals a multipercolation process, which governs the struggle of innovations trying to penetrate a market. We find that innovations thrive as long as they percolate in a population, and one becomes dominant when it is the only one that percolates. Besides offering a theoretical framework to understand the diffusion of competing innovations in social networks, our results are also relevant to model other problems such as opinion formation, political polarization, survival of languages and the spread of health behavior. This could help explain the homogeneity of forager social organization in common environments. 31 Succinct summary of a Network Theory for Evolution of Cooperation among Foragers. D.R. White 2012. *Definitions are given in the discussion. (1) The perspective, evidence and simulations presented here lead to a novel conception of human evolution as emerging from generalized cooperativity among archaic and later foragers, at variance with an intrinsic selfishness thought to imply universal competitive gaming, as Dawkins and Nowak suggested. (2) In general, for friendships, political & corporate alliances, growth of successful family groups, and, in kin groups--residence, inheritance and lower outmigration--, groups identified by structural (stru-)cohesion* show consistent side effects not replicable by other measures. White et al. citations. (3) Forager evolution benefited from large brains, recognition of extensive biparental kinship networks, and of marriage within the group, i.e., .structural endogamy (technically, 2-cohesive or bi-connected* networks of kinship). But forager population density is often so low -- !Kung 6.6pl/sqkm, 21 Inuit average 2.4pl/sqkm (Binford 2001)-- that stru-cohesion may be insignificant, with too few effective cycles. (4) Foragers at low densities have small tightly kin-integrated groups (family, band, composites of bands) with near-universal access to resources and use-rights mediated through kinship roles. Reputation for generosity is the basis for prestige and attempts at leadership domination are punished. Children acquire skills introduced by kin with diverse abilities and knowledge. Binford 2001. 32 (5) Stru-cohesion provides a basis for forager cooperation, augmented by pairwise k-cohesion* between ancestors with many children (White & Oztan), while stereotyped kinship roles (Murdock) such as Joking relations* can facilitate a direct basis for cooperation that is either group-extended, as between two subgroups marrying reciprocally, or as extended along chains, e.g., in trade partnership circuits. Within-generation cooperation is a common result of such role structures. (6) A second type of stereotyped pairwise roles that ameliorate potential kinship conflicts are those of Avoidance* of parents-in-law (which reduces conflict and loosens access to within-generation spouses) or Avoidance in WiBrWi and in Br/Si dyads (when siblings-in-law transitivity is at risk, e.g., in trader-circuits). (7) The great majority of foragers worldwide utilize these various mechanisms to facilitate cooperation, and have done so in the past. Below the forager packingdensity threshold (9.1/sqkm)*, Joking is most frequent, and declines with population density; while Avoidance is less frequent, and increases with population density. Both eventually decrease as complex societies develop with higher population densities. (8) As complex societies develop with high population density, local kinship networks may densify due to greater numbers of children, and as other nonkin relationships develop with high structural levels of cohesion, often marked by bullying others, success in defense of the group, and new conflict-avoidance mechanisms. 33 Cohesion and behavior 3rd-4th grades Links= self reported friendships classes with egalitarian (low-k) classes with hierarchical (hi-k) cohesion have little bullying, cohesion have bullying, bullies liked, aggressors unpopular <--(no class size effect)--> victims unpopular All: aggression corr. with popularity but neg. corr. with social preference. All: victimization neg. corr. with both pop.&pref but not corr.34 with aggression UC Davis Faris & Felmlee bullying study: school-wide Links= self reported friendships 12th green 9th 11th yellow 8th blue scattered N ~ 6-700 more bullying within grades than between 10th orange 10th dark orange Better interpretation in the next slide where variance is examined http://vidi.cs.ucdavis.edu/projects/AggressionNetworks/ 35 **Current Kinship Debate in Anthropology • Reacting to deconstructions of comparative concepts of kinship, Sahlins (2011a,b) has tried to define “what kinship is”: namely, “mutuality of being,” way way too vague • Shapiro (2012) reacts to this problem by defining parentage as a core idea, to which there are many demonstrable extensions in the concepts people use to refer to kinship, solving the problem posed by Schneider of defining kinship by how people genetically related. • Kronenfeld (2012) views a cross-cultural nexus around which all of the cognitive and behavioral strands of kinship cluster: the social placement of the new child, which collects the inventories that define various forms of kinship system. • The larger view is that kinship is not an it (Kronenfeld) but a network of differently organized relations and lexicons (White), behavioral and cognitive, defining elements and scaffolds within them, ramifying and connecting in ways that do not form a single closed entity. Tightness of integration (cohesion) of these parts is the effect of people interacting. 36 **OBSOLETE Summary. The pan-human biparental and role-based structure of human kinship, in all of its variants, provides low-density or egalitarian cohesive structure among foragers. This leads to a novel conception of human evolution, contra Richard Dawkins, from forager starting points of generalized cooperativity rather than an intrinsic selfishness thought to imply universal competitive gaming. One hypothesis tested is that network and stru-cohesion measures, now available in R (igraph), outperform existing rules of kin selection, genetic, and game theoretical approaches to the evolution of cooperation in human groups. That is, cooperation in networks is produced by an interaction between culture and evolutionary selection of gendered networks and group organization. These concepts apply to forager societies studied ethnographically and coded for ethnographic variables in Binford's "Frames of Reference" the "Kinsources" network datasets, and codings of formalized kinship behaviors. Each are tightly related to measures of social cooperation. A second hypothesis tested is that network measures of structurally cohesive groups have powerful causal predictions in social networks generally, and pairs of individuals linked to (stru-)cohesive groups . For foragers Joking creates direct cooperation and Avoidance reduces conflict, contributing in complementary ways to cooperation. 37 We have looked at network structure of Foragers below and above the packing threshold. Societies based on kinship networks as we have presented them, without additional structure relationships, have an intrinsic bicomponent structure complemented by specific kin behaviors: respect, informality, joking, license, and avoidance, for example. Third, studies of cohesive attachment to community, school, and cohesive sets of corporate partnerships/political attachments are predictive of numerous measures of social cooperation. Beyond Foragers. Hierarchical cohesive structure (of order 5 and higher), however, has been shown to lead to bullying and the nongenetic emergence of selfishness as network-dependent phenomena (next slides). At the level of interdependent families, foragers do not have k-cohesive (k-components) subgroups beyond k=2. In schools, subgroups of friendship networks with 2- or 3-cohesion are found empirically to be egalitarian. Here is a new research question: if we consider societies beyond the packing threshold as ones that develop complexity beyond biconnected kinship ties among families, i.e., adding new types of linkages such as hierarchies of groups and leaders and other forms of stacked and cross-cutting ties, is this have the analogous effect of supporting coalitions and bullying as occurs in gradeschools, highschools, and other organizations? 38 (-)Joking (+)Avoidances Table 1b. Linear regression of a densification measure with both Joking and Avoidance is nearly significant without removal of the !Kung outlier, p=.07 n=22, R2=.23. With adjustment of the outlier (to -5 not -22), p=.02, R2=.23. Like Br/Si Avoidance, regression of Excess (+)Avoidances over (-)Joking is also predicted by Fishing (p=.09). Because certain Avoidances eliminate many of the Joking relations, but not vice versa, Avoidances have precise interlocked structures. 39 Recall the anomalous !Kung sidedness These two-sidedness of these marriages, with low density, is random. Nonetheless there are lots of cross-kin relations, which are where Joking relations occur. With bride-service residence the marriages give a husband intermarriage use-rights for the resources of the bride. Joking dyads are inherently cohesive & their within-generation linkages are significant. Kin Avoidances with parents-in-laws lower conflicts but do not give use-rights. 40 1975 Hanover Network Symposium http://eclectic.ss.uci.edu/~drwhite/Networks/MSSB1975.html An early version of many findings for this talk were presented at this conference 41 Table 1c: Avoidance and Joking Relations related to low density & high dependence on hunting for the initial smaller sample of 24 foragers. Forager Avoidances Packorder D(10-F)=Lo Density times NonHunting (Gather and/or Fish) N (coded) =22 Adj.JokingRel Hunting Data# J:Joking&L:License v. A:Avoidance Teton 2 3.1 4 2X 9 2 #12 J Avoid Joking (- Missing data) Cheyenne 1 9.2 12 2X 8 4 # 9 J LoDPack&LoHunt<14 0 7 1 LoPack*LoHunt Kaska 0 1.5 2 2X 6 8 # 1 J HiDPack&LoHunt>13 Wind River 0 2X 6 8 # 3 - “ Pack*LoHunt14<19 2 3 1 Fisher Exact Tests Slave 0 10.8 14 2X 6 8 # 2 J “ Pack*LoHunt >19 7 2 1 are below Aweikoma 0 7.7 10 2X 6 8 # 5 L - - - - - - - - - - License an extreme form of Joking Rainy River 3 3.1 4 2X 6 8 #13 J HoPackLoHunt 9 5 2 Kaibab 0 6.2 8 2X 4 12 # 4 J P<0.007 (one tailed) p<0.015 (two tailed) 0;7;9;5 ------------------------------------!Kung 4 26.2 34 2X 3 14 #15 J Anomalous high levels of joking Eyak 3 3.1 4 2X 1 18 #14 J P<0.009 (one tailed) p<0.01 (two tailed) 2;10;7;2 Atsugewei 2 6.2 8 3 4 18 #20 J P=0.005 (one tailed) p<0.005 (two tailed) 2x3 test Diegueno 0 6.2 8 3 2.5 22.5 # 6 J D>18 (packorder Binford 2001:122#147)__ Cutpoint Guahibo 2 6.2 8 3 2 24 #19 J Luiseno 0 0.0 0 3 1 27 #18 - - - - No J No A ------------------------------------Attawapiskat 2 2 5-4-3M 12-14 #11 – Na7 N03c Murdock hunting: 4 (36-45%) 3 or 5 Arenda (N) 1 0.0 0 2X 4 12 # 8 A Chiricahua 2 0.0 0 2X 4 12 #10 A _______________________________________ Cutpoint Murngin 1 0.0 0 3 3 21 #16 A D>18 Theory: Avoidance fits here: beyond packing density Maidu (Mtn) 4 0.0 0 3 3 21 #21 A Avoidances replace Joking as suppression of conflict Vedda 7 0.0 0 3 3 21 #22 A (Packing density 3+ is a threshold to: Kutenai 1 0.0 0 4X 4 24 #24 A 1. Not everyone is kin Tenino 1 0.8 1 3 2 24 #17 A of Sister 2. Conflicts more likely Gilyak 9 2.3 3 3 1 27 #23 A 3. Competing claims over wife's sisters Haida 2 0.8 1 4 1 36 #25 A 4. Avoidance restrains conflict) /1.3 reduction ratio “The Tenino” Murdock 1980 Ethnology Mutual exclusion of Kin Avoidances(>1) & Joking Relations(>4) p<0.05 (2 tailed) Entailments: Lo density Hi Hunting --> 9 more Joking>Avoid p<.01 Fisher exact More Avoidances>Joking --> 7 Hi density NonHunting p<.01 (same by definition) Our Irvine Social Science Gateway can overlay such data from different coding projects. 42