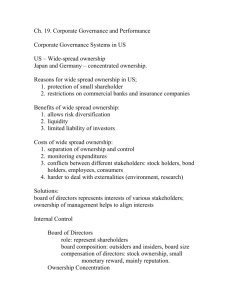

MANAGERIAL ENTRENCHMENT AND CORPORATE SOCIAL PERFORMANCE

advertisement