Packaging of Bio-MEMS: Strategies, Technologies, and Applications Robot and Servo Drive Lab.

advertisement

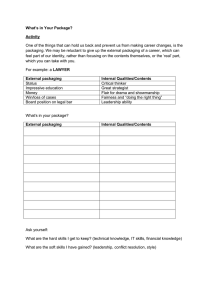

Robot and Servo Drive Lab. Packaging of Bio-MEMS: Strategies, Technologies, and Applications IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON ADVANCED PACKAGING, VOL. 28, NO. 4, NOVEMBER 2005 Thomas Velten, Hans Heinrich Ruf, David Barrow, Nikos Aspragathos, Panagiotis Lazarou, Erik Jung, Chantal Khan Malek, Martin Richter, Jürgen Kruckow, Martin Wackerle Professor: Ming-Shyan Wang Student: Ju-Yi Kuo Department of Electrical Engineering Southern Taiwan University of Science and Technology 2016/7/13 Outline Introduction STRATEGIES, TECHNOLOGIES, AND APPLICATIONS CONCLUSION ACKNOWLEDGMENT References 2016/7/13 Department of Electrical Engineering Robot and Servo Drive Lab. Southern Taiwan University of Science and Technology 2 Abstract Biomicroelectromechanical systems (bio-MEMS) are MEMS which are designed for medical or biological applications. As with other MEMS, bioMEMS frequently, have to be packaged to provide an interface to the macroscale world of the user. Bio-MEMS can be roughly divided in two groups. Bio-MEMS can be pure technical systems applied in a biological environment or technical systems which integrate biological materials as one functional component of the system. In both cases, the materials which have intimate contact to biological matter have to be biocompatible to avoid unintentional effects on the biological substances, which in case of medical implants, could harm the patient. In the case of biosensors, the use of nonbiocompatible materials could interfere with the biological subcomponents which would affect the sensor’s performance. Bio-MEMS containing biological subcomponents require the use of “biocompatible” technologies for assembly and packaging; e.g., high temperatures occurring, for instance, during thermosonic wire bonding and other thermobonding processes would denature the bioaffinity layers on biosensor chips. This means that the use of selected or alternative packaging and assembly methods, or new strategies, is necessary for a wide range of bio-MEMS applications. This paper provides an overview 2016/7/13 of some of the strategies, technologies, and applications in the field of bioMEMS packaging. Department of Electrical Engineering Robot and Servo Drive Lab. Southern Taiwan University of Science and Technology 3 Introduction MEMS for biological or medical applications or involving biological component(s), so-called biomicroelectromechanical systems (bio-MEMS) [1] are becoming more and more popular. Depending on their applications, this is justified by the inherent benefits of miniaturization in bio-MEMS such as small size, low weight, potential low unit costs per device, efficient transduction processes, high reaction rate, low reagent consumption, and the potential to manufacture minimally invasive devices and systems. A prominent medical application for bio-MEMS is the field of medical implants such as pacemakers, hearing aids and drugeluting implants to name a few. It is obvious that miniaturization is a key desirable requirement for implantable devices. This is especially true for implants in very small organs or those which are inserted using minimally invasive surgical procedures where the maximum allowable size is restricted by the diameter of the working channel in an endoscope. Department of Electrical Engineering Robot and Servo Drive Lab. Southern Taiwan University of Science and Technology 4 Medical implants are often rather complex systems and can consist of many components such as power sources, transducers, control units, modules for wireless communication, etc., potentially resulting in rather bulky devices if inappropriate packaging technologies are used. Example packaging technologies suitable for miniaturized and high-density bio-MEMS includes bare die assembly techniques like flip-chip technology. These, provide thin, small, and lightweight features and can be implemented on a multitude of substrates such as ceramic, laminate, molded interconnect devices (MID) as well as on flexible substrates. Very often, these processes use materials which are not biocompatible. In this case, additional encapsulation steps are necessary to avoid a direct contact between nonbiocompatible materials and body fluids or tissue. Another bio-MEMS category comprises biosensors or complete lab-on-a-chip systems for analytical tasks [2]. Biochips and biosensors are regarded as key elements for the development of multianalyte detecting instruments, especially of hand-held instruments for point-of-care or point-of-use testing. 2016/7/13 Department of Electrical Engineering Robot and Servo Drive Lab. Southern Taiwan University of Science and Technology 5 STRATEGIES, TECHNOLOGIES, AND APPLICATIONS A. Bio-MEMS Subsystems Partitioning Strategies 1) Material Trends: Bio-MEMS defines a diversity of microsystems functional embodiments. This diversity continues to expand as applications in different industrial sectors are developed [1]. One important domain of these developments is led by the miniaturization of systems for (bio)chemical and molecular analysis/synthesis [2]. This is driven by manifold reasons such as mass, volume, performance, and ergonomics considerations. Such multifunctional devices and systems may incorporate (bio)chemical, biological, electromagnetic, electronic, fluidic, and mechanical functionalities. Furthermore, they are truly three-dimensional (3-D), micro- and nanostructured and moving toward reconfigurable capability. Accordingly, to meet these diverse functions, fabrication materials are diverse, including polymers [3], diamond [4], metals [5], silicon [6], ceramics, glass [7], and hydrogels [8]. These materials are used as such but also in combination with selective surface customizations and coatings [9]. This move toward the use of nonsilicon matrices, particularly polymers, [10] has become particularly evident, and is driven by a combination of unit-cost manufacturing criteria and functional requirements (e.g., piezoelectric actuation, optical interconnection) that cannot be met by the use of silicon. Department of Electrical Engineering Robot and Servo Drive Lab. Southern Taiwan University of Science and Technology 6 2) Product Manufacturing Considerations: A principal technical challenge for the manufacturing of a system which is in part, or wholly, constructed of microcomponents is a generic and coherent strategy for integration including packaging. How this applies to products varies enormously as might be seen from two example broad product categories: Integrated Chemical Anaysis Microsystem (uTAS) Massively Parallel Biochemicals Synthesiser (uPLANT) 3) Modularity: Since the early conceptualization of microsystems with chemicals functionality [2], [11], contrasting approaches have been taken for the integration of miniaturized systems ranging from whole wafer [12] to modular configurations in two-dimensional (2-D) [13]–[15] and 3-D stacked [16], [17] formats. However, few of these earlier examples demonstrated the space-saving features that are characteristic of, for example, chip scale packaging (such as in SHELLCASE— see www.shellcase.com) with the consequence that assemblages of microcomponents became disproportionately large “miniature” systems. For some very large specific product markets. 2016/7/13 Department of Electrical Engineering Robot and Servo Drive Lab. Southern Taiwan University of Science and Technology 7 4) New Enabling Processes: New materials and processing techniques are required that can more readily accommodate the integration and packaging of environmentally sensitive materials such as biomolecules, organelles, and cells within microdevices and integrated microsystems. For instance, bioerodible polymers [18] are a class of materials that present new opportunities as a constructional material for biocompatible implantable microdevices (e.g., drugeluting stents) or package coating for temporarily implanted microsystems. The use of extremely short pulse lasers to substractively machine bioerodible polymers may be profitably extended to polymers which incorporate “active” ingredients. Low fluence conditions with short pulsewidth determines a very shallow damage zone [19] beyond which active ingredients may survive the machining process. Equally, advances in printing technology [20] and electrospray [21] are being explored as a “soft” process for the 2-D and 3-D overlay deposition of biomolecules such as peptides, growth factors, and biointerface coatings on microstructures. Such ballistic additive processes provide elegant, rapid, and dynamically programmable alternatives to traditional subtractive processes which frequently damage biological materials. New post-assembly processing techniques for incorporating biological materials [22] and synthetic molecular receptors [23] may also influence 2016/7/13subsystems packaging strategies and shift an emphasis to monolithically integrated Department of Electrical Engineering Robot and Servo Drive Lab. systems. Southern Taiwan University of Science and Technology 8 B. Methods for Microassembly of Bio-MEMS Bio-MEMS very often consist of a combination of sensors, actuators, processing, and communication circuits. Examples of such systems include miniature biochemical reaction chambers, lab-on-a-chip devices and systems, and micropumps. Various microfabrication methods that originate from the microelectronics industry, such as photolithography, UV Laser micromachining, and polymer embossing, have been developed to produce bioMEMS microparts. As the complete products are often comprised of components with mechanical moving parts (microvalves, micropumps, microreservoirs), microassembly processes are required. Microassembly is the discipline of positioning, orientating, and assembling of micrometer-scale components into complex microsystems. The general goal is to achieve hybrid microscale devices and systems of high complexity, while maintaining high yield and lowcost. So far, currentbio-MEMS assembling techniques follow the “pickand-place” approach, i.e., all components are assembled in one lengthy sequential process. This ultimately affects the cost of the microassembly process, raising it to more than 50% of the overall product cost [24]. An excellent paper that describes in detail MEMS manufacturing and microassembly issues is [25]. 2016/7/13 Department of Electrical Engineering Robot and Servo Drive Lab. Southern Taiwan University of Science and Technology 9 Automatic microassembly machines and robotic manipulation are also considered as solutions. Zhou et al. [26] successfully managed to combine vision and force sensors. The vision system provided feedback on the relative placement of parts over large ranges. A novel force sensor provided extremely precise feedback on the interactions among microparts as contact occurs. This strategy of combining visual and force feedback can be incorporated in automated microassembly machines or common pick-and-place systems, thus enhancing their efficiency and ability of performing more complex microassembly and packaging operations. Microassembly with robots requires extreme accuracy and precision. Typical robotic microassembly systems rely on the use of microgrippers for the manipulation of objects. There are various types of grippers proposed for physical contact manipulation (mechanical, thermal, electrostatic, piezoelectric, adhesive, vacuum). As an alternative, Fatikow et al. [27] proposed an assembly system with microrobots based on piezoelectric legs and equipped with a 3 Degree of Freedom (3DOF) gripper. A vision system provided a constant feedback of their position and orientation. A fuzzy controller evaluated the data and decided on the desirable behavior and movement of each robot. The advantage of this system lies in its flexibility, since different robot types can operate simultaneously by performing 2016/7/13different tasks. Department of Electrical Engineering Robot and Servo Drive Lab. Southern Taiwan University of Science and Technology 10 C. Technologies for Joining Polymer Bio-MEMS Components Polymer substrates have attracted great interest, particularly for life science applications and especially for low-cost and disposable devices. They require joining processes that are different from those developed for silicon or glass-based devices [35], [36]; in particular low-temperature bonding processes that do not necessitate the application of voltage, high pressure, or vacuum. In most cases, polymer microfluidic devices are sealed by adhesive joining [37]. Other techniques [38] such as lamination, direct and indirect (such as ultrasonic) thermal welding, solvent welding (in liquid or vapor phase), thermal bonding, and plasma bonding have been adapted to some extent to the need of polymeric microcomponents. New processes have also been developed for meeting their specific requirements [39], [40]. 2016/7/13 Department of Electrical Engineering Robot and Servo Drive Lab. Southern Taiwan University of Science and Technology 11 D. Packaging of Miniature Medical Devices In medical applications, miniaturization is key for implantable devices. Here, bare die assembly techniques like flipchip technology are the preferred choice, as they provide thin, small, and lightweight features and can be assembled on ceramic, laminate, MID molded, and flexible substrates. Flip-chip technology can substitute and complement conventional surface-mounted devices (SMD) or wire bonding processes for an even higher degree of miniaturization. The variety of technologies for those processes ranging from soldering to adhesive bonding offers solutions for a wide diversity of applications.The devices in which most advanced processes are being used are permanent implants such as pacemakers or eye pressure implants. New developments like brain implants for permanent monitoring or treatment (e.g., epilepsy) are also close to approval. Future developments will include concealed monitoring devices (e.g., sensor band aids or sensor-shirts) where microelectronic devices are integrated in clothing, closing the gap between medical therapy/diagnosis in the hospital and the ubiquitous monitoring of patients with a risk factor, as part of their everyday life. 2016/7/13 Department of Electrical Engineering Robot and Servo Drive Lab. Southern Taiwan University of Science and Technology 12 A crucial development in order to maximize these goals has been the development of ultrathin silicon devices as well as rerouting techniques to enable high-volume, low-cost manufacturing. The capability to fabricate thin integrated circuits (Ics) to less than 50 m thickness, thereby minimizing the total height of the assembly to a mere breadth of a human hair, is the enabling technology for flat and flexible systems. Also, respective interconnect techniques are required in order to maintain these ideal properties (Fig. 1). 2016/7/13 Department of Electrical Engineering Robot and Servo Drive Lab. Southern Taiwan University of Science and Technology 13 When ultrathin chips are not an option, the use of standard thickness chips can still enable extremely small devices by the use of flip-chip technology. Hearing aids are an excellent example which demonstrates the evolution from large boxes worn around the neck, to those now small enough to incorporate highperformance digital signal processor (DSP), microcontrollers, microphones, and batteries in one tiny inthe-ear device (Fig. 2). 2016/7/13 Department of Electrical Engineering Robot and Servo Drive Lab. Southern Taiwan University of Science and Technology 14 In order to increase the functionality per unit volume and simultaneously keep a given process flow (such as surfacemount technology (SMT)) the mounting, of bare die chips in an SMDcompatible form factor is possible. Sometimes termed chip scale packages (CSP), these can be mounted together with other SMD components in a high-volume capable process [96] without the need for special high-precision bonding equipment and/or ultrafine- line substrate technology. Examples here are pacemaker or defibrillator units, which employ digital and analog highperformance chips, which in a packaged or wire-bonded format would require significantly more space and weight 2016/7/13 (Fig. 3). Department of Electrical Engineering Robot and Servo Drive Lab. Southern Taiwan University of Science and Technology 15 An even more nonconventional understanding of system integration is given by the evolution of textiles and their ability to serve as substrates for electronic mounting. Although today’s scenarios are tested for sports and comfort, future concepts will well employ this integration also for home care or hospital monitoring. Direct assembly of microelectronic and sensor devices to, e.g., a T-shirt or a bed sheet, may allow much less intrusive forms of diagnosis and status tracking. Fig. 5 shows an example of an integrated electrocardiogr aphic (EKG) sensor into a worn T-shirt. The cables are currently required only to verify the performance against a metallic thread woven into the 2016/7/13 fabric of the textile. Department of Electrical Engineering Robot and Servo Drive Lab. Southern Taiwan University of Science and Technology 16 CONCLUSION Packaging of bio-MEMS plays an important role in providing bio-MEMS with an interface to the macroworld of the user. Many of the employed packaging methods stem from the packaging of nonbio-MEMS and have been adapted to biological or medical requirements. A new trend of using polymer bio-MEMS, mainly because of perceived economic reasons, has become evident. Many of the techniques known from packaging silicon-based MEMS cannot be applied to polymer bio-MEMS. In this paper, conventional packaging technologies, as well as novel technologies especially developed for polymer MEMS, have been presented. Considerations on strategies for partitioning subsystems within integrated subsystems have also been presented. These strategies strongly influence the number of packaging steps necessary for assembling the whole system and, thus, influence the costs of manufacture in which the packaging costs account for a very significant component. Several approaches for microassembly of hybrid microscale devices have been presented. These all aim to provide a means for the rapid, simple, and reliable positioning, orientating, and assembling of microcomponents into complex microsystems in order to enable a high-yield and throughput by unit reduction of microassembly costs. 2016/7/13 Department of Electrical Engineering Robot and Servo Drive Lab. Southern Taiwan University of Science and Technology 17 Special applications of bio-MEMS packaging such as packaging of a micropump for biological applications and packaging of a biosensor for analytical tasks have been presented. Within the packaged micropump, the fluid contacts only with three materials: 1) silicon, 2) the plastics of the housing, and 3) one glue between the housing and chip, to be selected depending on the requirements of the application. With that, this micropump can be used in various bio-MEMS applications. The presented BIOMIC biosensor was packaged to enable an early practical evaluation in the product development process which is an important asset in rapid product development. The relatively low yield of commercial biosensor developments can be attributed to a lack of feasible, functional, and economic packaging technology which hampers the transformation of a scientific biosensor into a commercial device. The selection of technologies for prototyping is also an important economic factor since the transformation mentioned above requires the major portion of the development costs. 2016/7/13 Department of Electrical Engineering Robot and Servo Drive Lab. Southern Taiwan University of Science and Technology 18 It is important to note the interdependence of the various microfabrication and assembly processes in the packaging chain. The chip layout design with the clearly separated functional domains, for instance, was a good basis for the chosen packaging techniques. It is clear that biochip design, fabrication, and packaging should be implemented as an integrated process. The examples presented for the packaging of bio-MEMS demonstrate that the choice of materials and processes for packaging are much more stringent for bio-MEMS than for pure technical MEMS. The same applies in some cases to the required density of packaging. An example are tiny medical implants. Here, the costs are less important than the size with the consequence that the most sophisticated packaging techniques can be applied. 2016/7/13 Department of Electrical Engineering Robot and Servo Drive Lab. Southern Taiwan University of Science and Technology 19 ACKNOWLEDGMENT T. Velten and H. Ruf would like to thank the other partners in the BIOMIC consortium for their fruitful and enjoyable collaboration. H. Ruf would also like to thank L. B. Larsen, from Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark, as well as M. Denninger and R. Haupt, from SMB, Lyngby, Denmark, for fabricating the microfluidic module and performing the underfill gluing of this module. He would also like to thank K. Misiakos from the Institute of Microelectronics/National Center for Scientific Research “DEMOKRITOS,” Greece, who developed the BIOMIC biosensor chip and who provided drawings of this chip. C. K. Malek would like to thank both Dr. R. Truckenmüller from the Institut für Mikrostrukturtechnik, Forschungszentrum Karlsruhe GmbH, for providing valuable materials and comments and Prof. O. Geschke, Mikroelektronik Centret (MIC), Technical University of Denmark, for helpful comments on bonding polymers. The authors would also like to thank S. Taylor of Cardiff University for the helpful manuscript revisions. Also, the writing of this review article was carried out within the framework of the EC Network of Excellence “Multi-Material Micro Manufacture: Technologies and Applications (4M).” 2016/7/13 Department of Electrical Engineering Robot and Servo Drive Lab. Southern Taiwan University of Science and Technology 20 [1] R. Bashir, “BioMEMS: State-of-the-art in detection, opportunities and prospects,” Adv. Drug Delivery Rev., vol. 56, pp. 1565–1586, 2004. [2] A. Manz et al., “Miniaturized total chemical analysis systems. A novel concept for chemical sensing,” Sens. Actuators B, Chem.,vol. B1, pp. 249–255, 1990. [3] H. Becker et al., “Polymer microfluidic devices,” Talanta, vol. 56, pp.267–287, 2002. [4] S. Guillaudeu et al., “Fabrication of 2-m-wide poly-crystalline diamond channels using silicon molds for micro-fluidic applications,” Diamond Rel. Mater. , vol. 12, pp. 65–69, 2003. [5] G. Kotzar et al., “Evaluation of MEMS materials of construction for implantable medical devices,” Biomater., vol. 23, pp. 2737–2750, 2002. [6] R. S. Shawgo et al., “BioMEMS for drug delivery,” Current Opinion Solid-State Mater. Sci., vol. 6, pp. 329–334, 2004. [7] K. Lee and L. Lin, “Surface micromachined glass and polysilicon microchannels using MUMP’s for BioMEMS applications,” Sens. Actuators A, Phys., vol. 111, pp. 44–50, 2004. Department of Electrical Engineering Southern Taiwan University of Science and Technology Thanks for listening 2016/7/13 Department of Electrical Engineering Robot and Servo Drive Lab. Southern Taiwan University of Science and Technology 22