JOHNS HOPKINS

advertisement

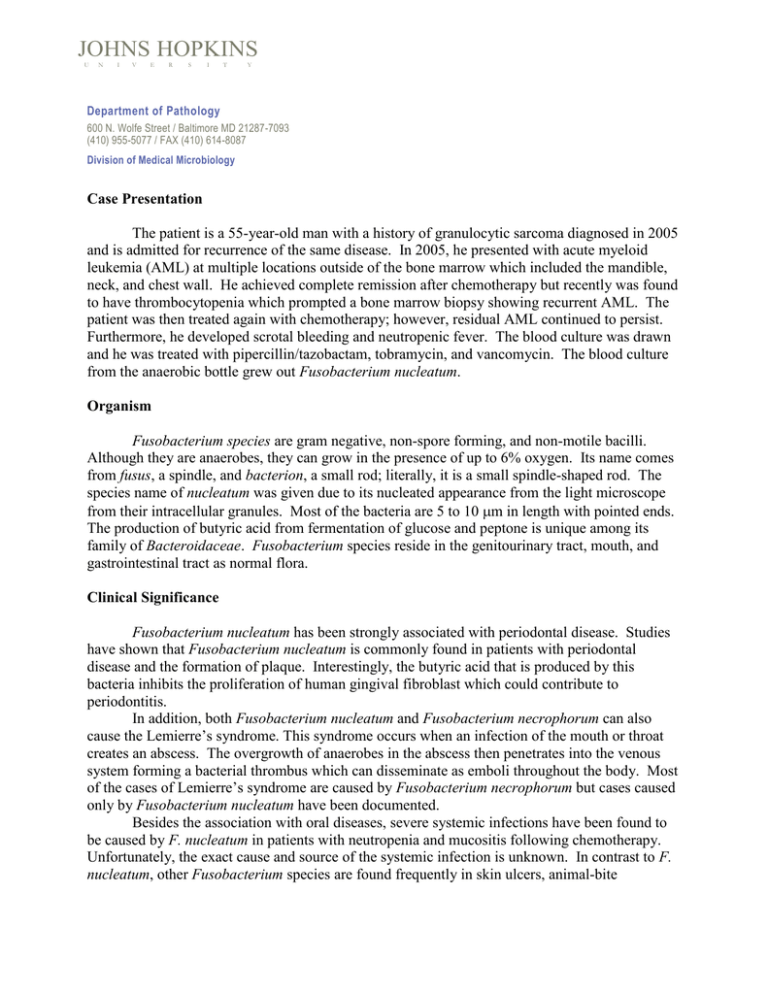

JOHNS HOPKINS U N I V E R S I T Y Department of Pathology 600 N. Wolfe Street / Baltimore MD 21287-7093 (410) 955-5077 / FAX (410) 614-8087 Division of Medical Microbiology Case Presentation The patient is a 55-year-old man with a history of granulocytic sarcoma diagnosed in 2005 and is admitted for recurrence of the same disease. In 2005, he presented with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) at multiple locations outside of the bone marrow which included the mandible, neck, and chest wall. He achieved complete remission after chemotherapy but recently was found to have thrombocytopenia which prompted a bone marrow biopsy showing recurrent AML. The patient was then treated again with chemotherapy; however, residual AML continued to persist. Furthermore, he developed scrotal bleeding and neutropenic fever. The blood culture was drawn and he was treated with pipercillin/tazobactam, tobramycin, and vancomycin. The blood culture from the anaerobic bottle grew out Fusobacterium nucleatum. Organism Fusobacterium species are gram negative, non-spore forming, and non-motile bacilli. Although they are anaerobes, they can grow in the presence of up to 6% oxygen. Its name comes from fusus, a spindle, and bacterion, a small rod; literally, it is a small spindle-shaped rod. The species name of nucleatum was given due to its nucleated appearance from the light microscope from their intracellular granules. Most of the bacteria are 5 to 10 m in length with pointed ends. The production of butyric acid from fermentation of glucose and peptone is unique among its family of Bacteroidaceae. Fusobacterium species reside in the genitourinary tract, mouth, and gastrointestinal tract as normal flora. Clinical Significance Fusobacterium nucleatum has been strongly associated with periodontal disease. Studies have shown that Fusobacterium nucleatum is commonly found in patients with periodontal disease and the formation of plaque. Interestingly, the butyric acid that is produced by this bacteria inhibits the proliferation of human gingival fibroblast which could contribute to periodontitis. In addition, both Fusobacterium nucleatum and Fusobacterium necrophorum can also cause the Lemierre’s syndrome. This syndrome occurs when an infection of the mouth or throat creates an abscess. The overgrowth of anaerobes in the abscess then penetrates into the venous system forming a bacterial thrombus which can disseminate as emboli throughout the body. Most of the cases of Lemierre’s syndrome are caused by Fusobacterium necrophorum but cases caused only by Fusobacterium nucleatum have been documented. Besides the association with oral diseases, severe systemic infections have been found to be caused by F. nucleatum in patients with neutropenia and mucositis following chemotherapy. Unfortunately, the exact cause and source of the systemic infection is unknown. In contrast to F. nucleatum, other Fusobacterium species are found frequently in skin ulcers, animal-bite infections and abdominal infections. Laboratory Diagnosis When colonies are identified on the plates grown under anaerobic conditions, a gram stain is performed. A long, slender gram negative rod is highly suspicious of Fusobacterium species. At this point, an API test can be performed which differentiates different bacteria by various biochemical reactions. In addition, the profile of antibiotic susceptibility can also aide in the identification of Fusobacterium species. Specifically, among the family of Bacteroidaceae, only Bilophila and Fusobacterium are resistant to vancomycin (5 g) but sensitive to kanamycin (1000 g) and colistin (10 g). Luckily, it is relatively easy to distinguish Fusobacterium from Bilophila, since the former is catalase, nitrate and 20% bile salt negative, and indole and lipase positive, whereas the latter is exactly the opposite (i.e. catalase, nitrate and 20% bile salt positive, and indole and lipase negative). Fatty acid analysis by gas liquid chromatography or molecular analysis of the 16S rRNA can also be used to identified Fusobacterium nucleatum. Recent studies show that rapid identification of Fusobacterium nucleatum and Fusobacterium necrophorum might be possible by using fluorescence in-situ hybridization (FISH). The FISH analyses rely on fluorescent labeled rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes specific for Fusobacterium nucleatum and Fusobacterium necrophorum. Treatment Management of fusobacterial infections usually begins with a beta-lactam. However, with the increase of beta-lactamase production in Fusobacterium species including F. nucleatum, F. mortiferum, and F. varium, the addition of metronidazole or clindamycin is recommended. If an abscess is present, drainage can help control the infection. Similarly, debridement of devitalized tissue can also be helpful. In cases of Lemierre’s syndrome or septic thrombophlebitis, heparin can shorten the course of illness. REFERENCES: 1. Sigge A, Essig A, Wirths B, Fickweiler K, Kaestner N, Wellinghausen N, Poppert S (2007). Rapid identification of Fusobacterium nucleatum and Fusobacterium necrophorum by fluorescence in situ hybridization. Diag Micro Infect Dis 58:255-259. 2. Bolstad AI, Jensen HB, Bakken V (1996). Taxonomy, Biology, and Periodontal Aspects of Fusobacterium nucleatum. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 9 (1): 55-71. 3. Duncan MJ (2005). Oral microbiology and genomics. Periodontology 2000 38:63-71. 4. Lemierre A (1936). On certain septicemias due to anaerobic organisms. Lancet 1:701-3. 5. Fanourgiakis P, Vekemans M, Georgala A, Grenier P, Aoun M (2003) Febrile neutropenia and Fusobacterium bacteremia: clinical experience with 13 cases. Supp Care Cancer 11(5):332-335.