You DO NOT need to write this section. It... for your review. CHAPTER 16

advertisement

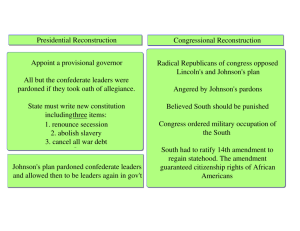

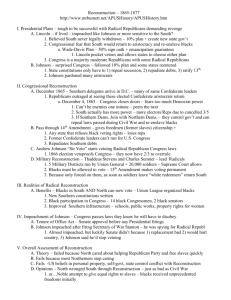

CHAPTER 16 THE AGONY OF RECONSTRUCTION TOWARD DISCUSSION - You DO NOT need to write this section. It is for your review. IMPEACHMENT Students generally believe that the President is a far more powerful political force than the Congress. There has even been talk of an “imperial presidency” developing in the United States. Students should therefore be reminded that in any serious confrontation between Congress and the Executive, Congress will win, as Richard Nixon can testify. The man who most bitterly learned that the Constitution gives Congress ultimate authority in our system of government was Andrew Johnson, the first President to have been impeached by the House of Representatives. Johnson was not a weak president. He vigorously exercised the ample powers given the President by the Constitution. Johnson, like Lincoln, used the power to pardon in order to reconstruct the South. This power, granted to the president in Article II, section 2 of the Constitution, is virtually unlimited. Johnson required Southerners to sign statements admitting their guilt in rebelling against the United States and requesting forgiveness. Johnson then granted their requests. Having been pardoned, the former rebels were legally innocent and should have been able to participate in all civic affairs, such as holding public office. There was a kind of ironic common sense in Johnson’s position. Because secession was an illegal act, no southern state had ever left the Union; the southern states, therefore, did not have to be reconstructed. In other words, there had never been a secession; there had been a rebellion, an act by individuals. Congress did not believe that the problem of southern reconstruction could be accomplished by having Confederate leaders admit or pretend to admit that they had committed a crime. Unless the social and political system of the South was fundamentally altered, Congress believed, the old planter elite would again come to power, and all the sacrifice of the Union army would have been in vain. Congress, therefore, refused to seat men elected to the House and Senate from states that Johnson considered to be reconstructed. Congress defended this exclusion on two interrelated grounds. First, Article I, section 5 of the Constitution gives Congress the right to determine the legitimacy of the election of its members. Congress ruled that all congressional elections in the South were invalid because, among other things, so many adult males (African Americans) had been unable to vote. Second, Article IV, section 4 gives the federal government the responsibility of ensuring that each state has a “republican” form of government. When the Constitution was written, the word “republican” clearly meant a government in which there was neither king nor hereditary aristocracy. By the early nineteenth century, the fear that any state might cease to be “republican” had disappeared, and Article IV, section 4 seemed like a dead letter, but in the sectional crisis of the 1850s, the Republican party began to argue that the southern states were not really republican because slavery gave all power to a small minority. “The people” had no political voice. In order to reconstruct the South so that it would be truly “republican,” Congress determined that totally new conditions would have to be created. This in turn meant, not only the abolition of slavery, but also the right of African Americans to vote. Congress had the upper hand in its struggle with Johnson. He could pardon individuals, but no Southerner would sit in Congress until Reconstruction was done the way Congress wanted. The president tried to use his powers as chief executive to sabotage Radical Reconstruction, by vetoing bills and by firing federal officials who did their jobs too well, but Congress proved again that it had superior powers. The Republicans, after 1867, had sufficient strength in Congress to override the president’s vetoes, and Congress rattled its ultimate weapon when it impeached Johnson. Altogether, Congress got its own way during Reconstruction. If fears linger that an “imperial” presidency is growing, it is well to be reminded that as long as Americans allow the Constitution to determine the ground rules of political life most power lies in the legislative branch of government, the one closest to the people. RELIVING THE PAST Reconstruction was lived most intensely by southern whites and blacks. African Americans learned of their freedom in many different ways. One African American woman remembered encountering Union troops when she was a little girl and being told, “Nigger! You is as free as us.” Another remembered that the plantation mistress assembled all the slaves before the great house, where she informed them that they were free, and then ordered them off her property. After emancipation, African Americans struggled through the Reconstruction period, not without some victories. One former slave, Henry Banner of Little Rock, Arkansas, summed it up this way: “In slavery I owns nothing and never owns nothing. In freedom I’s own my home and raise the family. All that cause me worriment, and in slavery I has no worriment, but I takes the freedom.” The best single collection of former slave narratives is that edited by George P. Rawick, The American Slave: A Composite Autobiography (Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing, 1972), 19 volumes. A good sample of the narratives collected by the Federal Writers’‘ Project in the 1930s is B. A. Botkin, editor, Lay My Burden Down (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1945). It should be remembered that Reconstruction failed to break the spirit of white Southerners, who began to shape a society much like the one that existed before the war. There is an excellent collection of letters sent to one another by members of a large and well-off Georgian family in The Children of Pride, edited by Robert Manson Myers (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1972). Among the more notable examples of the South’s defiant, “unreconstructed” attitude are the letters sent by Caroline Jones to her mother, thanking God for the assassination of Lincoln, and the letter dated December 9, 1865, from Mary Jones to her daughter, telling her about the troubles she was having with the Freedmen’s Bureau. ROBERT SMALLS AND BLACK POLITICIANS DURING RECONSTRUCTION The author demonstrates the frustrating failure of Reconstruction through the biography of Robert Smalls, who escaped slavery in South Carolina, joined the Union military effort, and enjoyed a successful career in business and politics after the war, until the return of white supremacy. Begin copying the review here: THE PRESIDENT VERSUS CONGRESS The North split on the question of reconstructing the South. Some Northerners, led by the White House, wanted speedy Reconstruction with a minimum of changes in the South. Other Northerners, led by Congress, wanted a slower Reconstruction and demanded that the freed African Americans be protected. A. Wartime Reconstruction Even Lincoln clashed with Congress over Reconstruction. Lincoln hoped to win Southerners from the Confederate cause by announcing a lenient policy in 1863. Congress, however, resented Lincoln’s assumption that he alone could determine policy, and some Congressmen wanted to make black suffrage a precondition for taking the South back into the Union. Most of all, Congress did not trust white Southerners. Lincoln and Congress could not agree on the issue and it was left to Lincoln’s successor to work out a Reconstruction policy. B. Andrew Johnson at the Helm Johnson, a Southern Democrat, had remained loyal to the Union and was rewarded with the vicepresidency in 1864. At first, Radical Republicans felt enthusiastic about Johnson, because he had a long record of hostility toward the great planter class. Gradually, however, Johnson split with the Republican party. Johnson began the process of Reconstruction by instructing the Southern states to hold conventions that would declare secession illegal, repudiate the Confederate debt, and ratify the Thirteenth Amendment. The conventions did as ordered, but did so reluctantly, and none of them gave African Americans the right to vote. In fact, the southern states passed “Black Codes” that put African Americans into a kind of semislavery. Johnson approved of the actions of these conventions; Congress did not. C. Congress Takes the Initiative Congress insisted that African Americans be given the vote. In part, this insistence reflected political partisanship, since the Republican party expected to get the black vote. For the most part, however, the desire to give the franchise to African Americans grew from an ideological commitment to equal rights and a fear that without black suffrage the South would again fall under the control of the great planters. In 1866, when Johnson vetoed two bills designed to help the freedmen, Republicans felt betrayed. In order to protect the rights of African Americans from a president they no longer trusted, the Republicans pushed the Fourteenth Amendment through Congress. In the elections of 1866, Johnson organized the National Union party, which ran against Republican congressmen. The results of the election, however, strengthened the Radical Republicans in Congress. D. Congressional Reconstruction Plan Enacted Congress began enacting measures that are collectively called “Radical Reconstruction.” The South was placed under military rule until black suffrage was fully secured. The more radical Republicans realized that the African Americans needed a long period of federal protection, but the Republican party in general felt uneasy about the military occupation and wanted it to be short. E. The Impeachment Crisis When Johnson sabotaged Radical Reconstruction in the way he administered it, Congress moved to remove him from office. The House impeached him in February 1868, but the Senate refused to convict. Popular opinion had begun to turn against the Radical Republicans, who seemed willing to subvert the Constitution to accomplish what they wanted. RECONSTRUCTING SOUTHERN SOCIETY The South was an arena with three contending parties: Southern whites who wanted to keep the newly freed blacks in an inferior position, Northern whites who moved to the South to make money (“Carpetbaggers”) or to “civilize” the region, and blacks who wanted equality. Eventually, the forces of reaction and racism won because the federal government did not sustain its interest in Reconstruction. A. Reorganizing Land and Labor Faced with a massive need to rebuild, the South had to find a new labor system. The ex-slaves preferred to work their own land and were sometimes given land by the federal government. Under Johnson, most of this land reverted to white ownership. The former slave-owners tried to impose a contract labor system resembling slavery, but blacks insisted instead on sharecropping, which seemed like a first step toward economic independence. Sharecropping soon proved to be a form of peonage. B. Black Codes: A New Name for Slavery? The South became an increasingly segregated society after the Civil War. As whites returned to political power, they enacted “Black Codes,” harsh laws that reduced blacks to a condition little short of slavery. The federal government often intervened to annul the Black Codes, but a reign of terror and unpunished physical violence robbed blacks of the gains they had achieved in the years just after the war. C. Republican Rule in the South The Republican party was not organized in the South until 1867, and it never acquired much strength. At first it attracted three groups, all with different aims: businesspeople, who wanted government aid, small white farmers, who wanted protection from creditors, and blacks, who formed the majority of the party and who wanted social and political equality. The Republican coalition was inherently unstable and broke up when the whites left it. D. Claiming Public and Private Rights The Republican party in the South improved conditions in areas such as public education, welfare, and transportation, but because too many Republican state legislatures were corrupt, although no worse than those in the North, the entire Reconstruction effort was tarnished. Ironically, white Southerners mainly blamed African Americans for crooked, inefficient government, even though blacks never controlled most Southern legislatures during Reconstruction. RETREAT FROM RECONSTRUCTION Grant faced problems that might have defeated a better president, but he contributed to his own failure. He was not a man with strong principles. A. Rise of the Money Question Grant won the election of 1868 because he was a war hero. There were no clear-cut issues in the campaign, but after the Panic of 1873, the money question became paramount. Debtors, especially in the Midwest, and business people everywhere, wanted the government to follow an inflationary policy by allowing “greenbacks” issued during the Civil War to remain in circulation. Bankers, merchants, and intellectuals supported a return to hard money. In 1874, Congress adopted a pro-greenback position, but Grant opposed it. In 1875 the government committed itself to hard money, thereby arousing the anger of those suffering most from the depression. A Greenback party was formed, and it did well in congressional races. B. Final Efforts of Reconstruction In 1869, Congress passed the Fifteenth Amendment to give equal rights to vote to black males. The exclusion of women in the amendment created a split in the feminist movement, but seemed to assure Republican political ascendency in the South for decades to come. C. A Reign of Terror Against Blacks Various loosely organized vigilante groups in the South, most notably the Ku Klux Klan, unleashed a reign of terror against blacks and whites who joined the Republican party. At first, Grant and the northern Republicans took a hard line against the Klan, but when the Democratic party began to make political gains by criticizing the continued repression of Southern whites, the Republican Party became less inclined to support blacks if it meant losing white votes. Without the federal government to protect them, blacks were systematically excluded from political life, and by 1876 Republicans controlled only South Carolina, Louisiana, and Florida. Forceful measures would have quashed terrorism in the South eventually, but the northern public grew tired of the effort. D. Spoilsmen Versus Reformers During Grant’s first term, stories of government corruption disturbed many Americans and discredited the Republican party. In the election of 1872, a new party, the Liberal Republicans, was organized and nominated Horace Greeley for president. The Democrats also nominated Greeley, but Grant won reelection easily. It was during his second term that the full story of government corruption unfolded. REUNION AND THE NEW SOUTH North and South reconciled after 1877, but only when it was agreed to strip African Americans of their political gains and to favor the interests of big business over those of the small farmer. A. The Compromise of 1877 Nobody knew who won the election of 1876. Democratic candidate Samuel Tilden got most of the popular votes, but there was so much dispute about the electoral vote that Republican Rutherford B. Hayes had a chance. Congress appointed a special commission to determine who should get the disputed electoral votes. When it became clear that the commission would give the votes to Hayes, the southern Democrats in Congress promised not to cause trouble if the Republicans would guarantee federal aid to the South as well as removal of all remaining federal troops. When Hayes agreed, Reconstruction came to an end. B. “Redeeming” a New South The men who replaced the Republicans in running the South, the “Redeemers,” were more interested in commerce or manufacturing than in agriculture. They used the doctrine of white supremacy to gain and hold power, but their chief interest was in making the South a modern, industrial society. The Redeemer regimes, often corrupt, welcomed northern investment, and northern control of the southern economy. These governments neglected the problems of small farmers, black or white, who suffered from unpayable debts. Eventually, the small farmer organized his own political party in the 1890s. C. The Rise of Jim Crow The Redeemers also began the process of legal segregation and invented ways of denying blacks the right to vote. Blacks trying to vote Republican were whipped or even lynched, but even blacks who wanted to vote for Democrats were turned away by cynical rules enacted for the sole purpose of keeping elections wholly white. Politically powerless, blacks were subjected to degrading segregation laws whenever they used public facilities. CONCLUSION: HENRY McNEAL TURNER AND THE “UNFINISHED REVOLUTION” The author ends the chapter with a capsule biography of a free black who, like Robert Smalls, enjoyed a distinguished political career after the war, but who was eventually forced out of government by the return of white supremacy. At one time convinced that blacks and whites would live together in equality, Henry Turner, a Methodist bishop, ended by preaching that the only hope for American blacks was to emigrate to Africa.