Econ 201 Ch. 2 Economics: Foundations & Models

advertisement

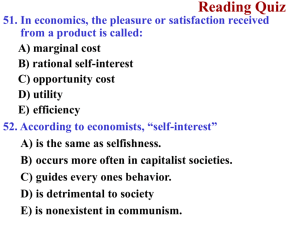

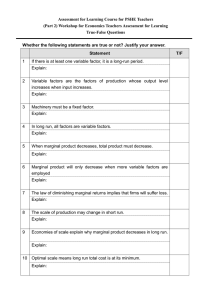

Econ 201 Ch. 2 Economics: Foundations & Models Or Thinking Like and Economist Building a Model • Why? – Explain the past and/or predict the future – Understand factors that motivate individuals and firms to take the actions that they do in the marketplace – Possibly be able to influence the decisions they make • Make the markets more efficient -> create bigger benefits for all (consumers and firms) What Comprises a Model? • Hypotheses and/or assumptions about how consumers and firms behave – Hypos/assumptions may be testable or nontestable (“maintained”) – When you construct the model you need to specify which is which • Not always done – author may be unaware of “implicit” assumption Overview • Basic assumptions underlying economic modeling – Rationality and self-interest • Tradeoffs: evaluate benefit/costs of “relevant” alternatives • Marginal analysis – Totals versus marginal (incremental analysis) • Basic questions economics addresses • Alternative Market approaches to production and allocation • Modeling and the Scientific method An Example • Consumer Demand Model – Assume that individuals are “rational” – Assume that they will act in their own self interest • Implications – Self-interest • Will want more, rather than less of a good • No altruism, i.e., sacrificing their own well-being for others Basic Assumptions • People are rational – Implications • When price increases then quantity demanded/purchased decreases • Testable/maintained – Rationality – observable from market data • Key assumption – Self-interest – harder to observe • May not significantly impact major implications 1. Rationality • Individuals will make economic decisions in their own best interest, based on the information that they have available – Imperfect information (due to costs of obtaining it, difficulty in interpreting and evaluating it) may “appear” to lead to less than “optimal” or “best” choices • Gary Becker’s weaker assumption – Individuals do not systematically make irrational decisions 1. Rationality • An example: the First Law of Demand – As the price per unit of the good declines, a consumer (all other things held constant, e.g. their income) will choose to buy more of the good over the same time period 1. Rationality • Becker’s point – As long as people don’t always buy more when the price goes up and even if they randomly buy more/less; they will behave as though they are adhering to the First Law of Demand • A more rigorous version (for consumers) – Individuals seek to maximize their utility/satisfaction subject to their income/budget constraint 1. Rationality • More rigorously: Max U ( x, y ) subject to I pxQx p yQy 2. People Respond (rationally) to Economic Incentives • An example (Hubbard and O’Brien) – Average age of the populations of US, Japan and most Europeans countries are getting older • Declining birth rates (below replacement level) • People living longer • Post WWII baby boom (“mouse in the python”) • Challenge for governments as – Social security and medical care payments will increase as larger % of population retires – Fewer younger folks replacing them in the workforce • -> tax payments are decreasing An Interesting Solution • Estonia – UN estimated that population would decline by 0.7M by 2050 (from 1.4M to 0.7M) – Starting in 2007 • Working women paid entire salary up to 15 months for having a child • Non-working: $200 per month (avg income ~$650) – Impact • Birth rate increased from 1.6 to 2.1 children per woman • 45 other european countries in the process of adopting a similar set of incentives Learning Objective 1.1 Making the Connection •Will Women Have More Babies if the Government Pays Them To? The Estonian government is encouraged by the results of providing economic incentives and is looking for ways to provide additional incentives to raise the birthrate further. 3. Optimal decisions are made at the “margin” • What do we mean? – When making an economic decision, e.g. to purchase 1 more unit of a good, we compare the marginal (or incremental) benefits against the marginal costs • For example – When studying for an exam • Given you’ve already studied 8 hours, when deciding whether or not to study 1 more hour, you compare – the expected benefits (a “marginal” improvement in your grade – Versus the next best (highest valued) use of your time » E.g., sleeping, eating, time with friends Marginal Decisions • Back to the First Law of Demand – How much of a good do you buy? • If the marginal/incremental value of the next unit is less than what it costs, are you willing to buy it? MV < price Don’t buy! MV < price Do buy! Totals versus Marginals • When you make a “consumption” decision – You may be comparing Total Value of consuming x amount of the good (TV(x)) to the Total Cost (TC(x)) – But it’s really a step-wise comparison • If TV(9) > TC(9) – Buy at least 9 – then check at x =10 • If TV(10) < TC(10) – Stop at 9 – MV(10th unit) less than MC(10th unit) – Easier and faster (fewer calculations) to compare marginals than totals Optimal Decisions Made at the Margin • For consumers – If price > additional/incremental/marginal “use” value of the good -> don’t buy – If price < MV -> buy • For suppliers – If P > marginal costs of producing that last unit -> supply it to the marketplace (sell it!) – If P < MC then don’t produce it Key Questions in Economics • What goods and services will be produced? • How will the goods and services be produced? • How will the goods and services be allocated? – How do we decide who gets them? A Simplification of Market Types • Two Extremes 1. Centrally Planned Economies – Government determines what goods get produced, who produces them and how they are allocated – E.g. Soviet Union’s 5-year plan (1917-1991) 2. Market Economies – Market determines all – – – Prices signal consumer willingness to pay for goods and services Firms respond to price signals by comparing consumers WTP to the firm’s (marginal) cost of producing goods Goods are allocated to those with highest WTP (and hence value them most) In Reality • Real-world markets have mixes of both Market and Centrally planned structures – Market failure may require government regulation (e.g., monopolies, pollution, fisheries) – Public goods may require subsidies (e.g., national defense, education, clean energy) – Lobbying to protect certain groups • Dairy farmers, energy producers Scientific Method Economic Models • The Scientific Method (Hubbard and O’Brien) 1. Decide on assumptions to be used in developing the model 2. Formulate a testable hypothesis 3. Use economic data to test the hypothesis 4. Revise the mode if it fails to explain well the economic data 5. Retain the revised model to help answer similar economic questions in the future Role of Assumptions • Assumptions – Role of assumptions is to • reduce the complexity of the problem to its key elements and, • focus on the items that have the most significant impact (“80/20” rule) – 80% of the impact is due to 20% of the factors • Robust – If relaxing the assumptions has minimal impact on your conclusions then the model is deemed “robust” and is largely unaffected by these testable or nontestable assumptions – “robustness” is a desirable property Normative and Positive Analysis • Positive economics – “what is”, e.g., if prices go up, quantity demanded will go down • If rates increase faster than the rate of growth in income then demand for telephone (or electricity) services will decline • Normative economics – “what ought to be” or “what is fair” • Everyone should be able to afford basic telephone (or electric) services – “universal service” mandate Macro- versus Microeconomics • Microeconomics – Focuses on analysis of consumers and firms in specific individual markets • E.g., automobile, PC computers, wireless telephone service – Several sub disciplines • Labor, Industrial Organization, Natural Resources, Industry Types, Theory, International Trade, Finance, Health Care • Macroeconomics – Focuses on aggregate economic behavior • All markets lumped into GDP = C+I+G+NX • Look at impact of government impact (taxes, subsidies, regulation, monetary and fiscal policy), trade policies on GDP, employment Economics as a Social Science • Is economics a science? Key Point • A Key or Critical Point – If the assumption is not testable – • how “robust” are the model’s predictions if the assumption is false; that is how sensitive is the model to the assumption • If it assumption is not testable we have to be very sensitive to this – If the assumption is testable • Still need to know “sensitivity” • Model can be rejected or accepted depending on test results