Micro-level modelling to identify the separate effects

advertisement

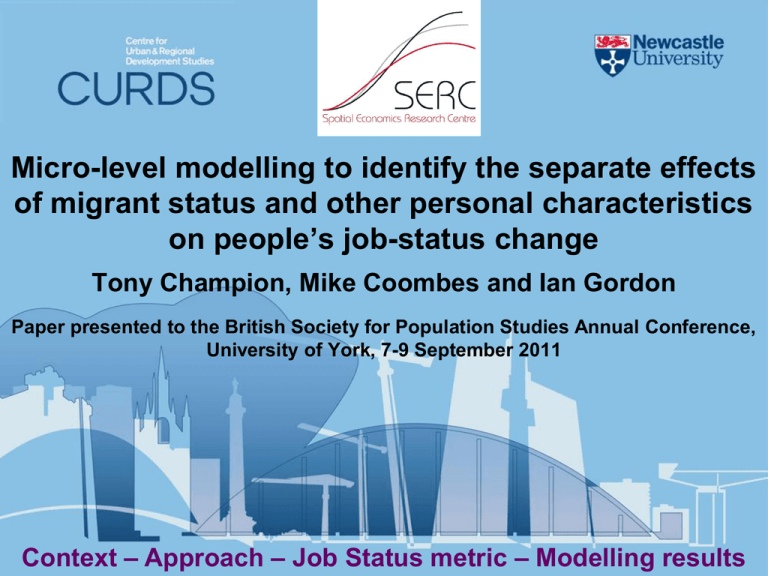

Micro-level modelling to identify the separate effects of migrant status and other personal characteristics on people’s job-status change Tony Champion, Mike Coombes and Ian Gordon Paper presented to the British Society for Population Studies Annual Conference, University of York, 7-9 September 2011 Context – Approach – Job Status metric – Modelling results Acknowledgements & disclaimer This presentation reports on part of a project on skills and career development undertaken for the Spatial Economics Research Centre funded by ESRC, BIS, CLG and the Welsh Assembly Government The authors are grateful to Colin Wymer for the map Census output is Crown copyright and is reproduced with the permission of the Controller of HMSO and the Queen’s Printer for Scotland The permission of the Office for National Statistics to use the Longitudinal Study (LS) is also gratefully acknowledged, as also is the help provided by staff (notably Christopher Marshall) of the Centre for Longitudinal Study Information & User Support (CeLSIUS). CeLSIUS is supported by the ESRC Census of Population Programme (Award Ref: RES 34825-0004) This presentation has been cleared by ONS (Clearance Number 30112I), but the authors alone are responsible for the interpretation of the data Analytical context 1 Dual focus on people and place: whether places differ in how far they help their residents achieve career progression and hence whether people benefit much from moving to/from certain places (as hypothesised in Fielding’s ‘escalator region’ model) Literature on agglomeration suggests the large labour pools of big cities improve the matching of supply and demand, hence higher productivity for cities and improved prospects for career progression for residents (including in-migrants) Some large cities – especially London – have achieved strong growth in knowledge industries, creating more opportunities for high-level professionals and managers Linked Census records in the LS (a 1.096% sample) are used to track people over time, both in terms of their labour market status and their spatial location (i.e. social and spatial mobility) Analytical context 2 • This project’s point of departure is Fielding’s ‘escalator region’ (ER) hypothesis which involves: - the ER providing faster social mobility than other regions - people moving from other regions to ‘step on to the escalator’ and achieving even faster social mobility than the ER’s longer-term residents - people ‘stepping off the escalator’ later in their lives for a better quality of life even if seeing a drop in job status • The project updates and extends elements of Fielding (1992 etc.) by: - examining 1991-2001 (cf 1971-81 or 1981-91) - shifting the spatial focus to the urban scale (cf regional) - using a single-scale measure of job status (cf ‘social groups’) - adopting micro-level modelling to identify key determinants of career progression (cf probability of transitioning between ‘social groups’) • Its main aim is to see how far any other cities can emulate the ‘escalator’ function of London (the core of Fielding’s ER of South East England), but this paper’s main focus is on gauging the separate effect of migrant status Aim of and approach to this analysis Analytical approach: micro-level modelling that attempts to allow for all the factors that influence people’s occupational mobility alongside the place where they live Modelling approach: general linear modelling of a continuous variable of career development, with the explanatory variables comprising a set of personal characteristics including migrant status and place Migrant status/place: people classified by usual residence in 1991 and 2001 by reference to a set of 38 City Regions that constitutes a full regionalisation of England & Wales (except Berwick) Measure of career progression: a single Job Status (JS) scale across the occupational spectrum, based on log of median hourly earnings of each SOC90 category for mid 1990s derived from modelling LFS Dependent variable: change in individuals’ JS scores 1991-2001, scaled in terms of the proportionate change in earnings that they might expect from any change in occupation (no change = 0) Population modelled: all ONS Longitudinal Study members aged 16-64 in 1991 (26-74 in 2001) who were in work at both the 1991 and 2001 Censuses and had a valid SOC90 in 1991 and 2001 (N=c130k) 38 City Regions based on best-fit local and unitary authorities Source: derived by Mike Coombes Change in JS scores 1991-2001 for all individuals Source: Calculated from ONS Longitudinal Study. Crown copyright. Based on rounded data in the histogram, the modal category is little or no change, but there is a fairly wide spread around this, downward as well as upward. In terms of unrounded JS scores, no change in JS = 36.8%; upward shift = 35.6%; and downward shift = 27.7% A) Mean change in Job Status score A: Mean change in Job Score, 1991-2001 0 0.01 0.02 0.03 0.04 0.05 0.06 0.07 All B) % distribution of JS change by down/same/up, by migrant status Migrants 91-01 Non-migrants 91-01 Non-migrants 81-91-01 Non-migs 91-01 but migs 81-91 B: 0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100% All Migrants 91-01 Non-migrants 91-01 Non-migrants 81-91-01 Non-migs 91-01 but migs 81-91 JS down JS exactly the same Source: Calculated from ONS Longitudinal Study. Crown copyright. JS up % distribution of change in Job Status score 1991-2001, by gender and age in 1991 0% 20% . 40% 60% 80% All Males Females Males 16-24 Males 25-34 Males 35-44 Males 45-54 Males 55-64 Females Females Females Females Females 16-24 25-34 35-44 45-54 55-64 JS down JS exactly the same JS up Source: Calculated from ONS Longitudinal Study. Crown copyright. 100% Results for personal characteristics: Job Status in 1991… 0.70 0.60 0.40 0.30 0.20 0.10 ) (r ef 19 20 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 0.00 1 coefficient 0.50 Job Score in 1991 (20-iles, 1=lowest; 20=highest) Source: Calculated from ONS Longitudinal Study. Crown copyright. …Gender, Age, Marital status, Dependent child … 0.20 0.15 Dependent Child in household 91 and/or 01? 0.05 -0.05 Gender Age Si ng M le a R rrie em d ar r D ied iv W id orc ow e ed d (r ef ) D C 91 & D 0 C 01 1 N on D o C ly D 0 C 91 1 o nl & 01 y (r ef ) 16 -1 9 20 -2 4 25 -2 9 30 -3 4 35 -4 4 45 -5 55 4 -6 4 (r ef ) m m a al le e (r ef ) 0.00 fe coefficient 0.10 Marital status -0.10 Source: Calculated from ONS Longitudinal Study. Crown copyright. …Birthplace, Immigration year, Ethnicity, Religion… Source: Calculated from ONS Longitudinal Study. Crown copyright. …Illness, Type of working, Social Class, Qualifications… Source: Calculated from ONS Longitudinal Study. Crown copyright. …Industry of job (top & bottom 10 of 52 sectors)… Top 10 and bottom 10 coefficients for Industrial Sectors (out of 52) Computing and related activities Act auxilliary financial intermediation Education Manuf office machinery and computers Insurance and pension funding, etc Financial intermediation, etc Collection,purification/distri of water Post and telecommunications Public admin/defence; compulsory SS Manuf chemicals and chemical products Activities membership organisations nec Agriculture/hunting/forestry/fishing Manuf food/beverage/tobacco products Manuf pulp, paper and paper products Other service activities Manuf textiles Retail trade, except of motor vehicles Manuf apparel;dressing/dyeing fur Tanning/dressing of leather, etc Mining coal/lignite; extraction of peat -0.10 -0.05 0.00 0.05 0.10 0.15 coefficient Source: Calculated from ONS Longitudinal Study. Crown copyright. 0.20 …City Region of residence in 2001 (top & bottom 10 of 38)… Top 10 and bottom 10 coefficients for City Regions (out of 38) Reading London Coventry Northampton Cambridge Worcester Liverpool Manchester Birmingham Oxford Lincoln Hull Derby Bradford Shrewsbury Carlisle Swansea Chester Plymouth Exeter -0.10 -0.05 0.00 0.05 0.10 0.15 coefficient Source: Calculated from ONS Longitudinal Study. Crown copyright. 0.20 Anything left for Migration Status? (A) Moved between the 38 CRs or not? (B) Moved 40km+ between CRs or not? coefficient (A) 91/01 Migrant status -0.10 -0.05 0.00 0.05 0.10 0.15 Stayed in same City Region 91/01 Changed City Region 91/01 (ref) (B) Distance of move Moved <40km and City Region stayers Moved 40km+ between City Regions (ref) Source: Calculated from ONS Longitudinal Study. Crown copyright. 0.20 Summary of results from modelling JS change The most important determinants of 1991-2001 change in JS score (allowing for the role of all the other variables in the model) are: • Job status 1991: lowest-JS starters rise fastest, highest rise the slowest • Gender: more positive (i.e. higher) JS change for men than women • Age: highest for those aged 16-19 in 1991 (26-29 in 2001), with very regular reduction with age • Social class: clear separate effect, with IIIN highest, followed by SC I & II • Qualifications: clear separate effect, with Higher Degree highest • Industrial sector: computing highest, mining & tanning lowest • City Region of residence in 2001: Reading & London highest, Exeter & Plymouth lowest (but barely 5% range) Relatively minor effects (mainly <5% range, most <2.5%): Marital status; Dependent child in household (and change in this); World region of birth; Year of immigration; Ethnicity; Religion; Long-term limiting illness (and change in this); Type of working Allowing for all these variables, what role left for (Internal) Migrant Status? • Higher rise for inter-CR migrants 91-01 (cf. non-migrants) • Higher rise for those moving 40km+ (cf. <40km migrants/non-migrants) • Both these effects small (3% and 1% respectively) Next steps • Experiment with alternative and more specific measures of inter-CR migration (e.g. move to/from London or up/down city-region hierarchy) • Attempt to separate the ‘step-up’ effect (JS change at time of move) from a ‘pure escalator’ effect (JS move afterwards), e.g. by looking at effect of moving in previous decade (or using an alternative data source that monitors annual change) • Replace 1991-based personal characteristics with variables that try to reflect people’s ‘decadal’ experience (e.g. where they change industry or city region) • Incorporate interaction terms, e.g. gender with ethnicity • Do more to identify the types of people who gain most from being in the ‘right place’ and how this reflects on the role of place Micro-level modelling to identify the separate effects of migrant status and other personal characteristics on people’s job-status change Tony Champion, Mike Coombes and Ian Gordon tony.champion@ncl.ac.uk mike.coombes@ncl.ac.uk i.r.gordon@lse.ac.uk