International Relations Theory and Asia Studies: the 1990’s Overview 2013/04/07, Kazuhiko Togo

advertisement

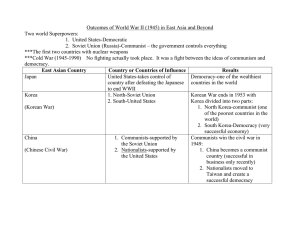

International Relations Theory and Asia Studies: the 1990’s 2013/04/07, Kazuhiko Togo Overview In the five decades from the 1970’s to the 2010’s that this study is addressing, the 1990’s stand out as the decade which marked the turning point of these five decades. If one is to choose one single event which transformed the world structure both globally and in Asia in these five decades, one may agree that it is the end of the Cold War that took place somewhere between 1989 to 1991. Before this turning point, the global structure was characterized by the rivalry between the two blocks, the capitalist block led by the United States and the Socialist block led by the Soviet Union. The global peace was ensured by the super-power rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union, at the center of which lied the key issue of nuclear parity, which took the form of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD) system of nuclear weapons. But by 1989-1991, the Soviet Union disintegrated and the Cold War ended. The Socialist bloc became the vanquished and the capitalist block appeared as the victor and the United States became world’s only super power. The post-Cold War world structure was first of all an outcome of this divide between the victor and the vanquished. Policies adopted by the Cold War victor, that is the United States, Korea and Japan and the Cold-War vanquished, the Soviet Union and China are the results of this winner-loser difference. But the international politics of the 1990’s were deeply influenced by not only the facts that a country faced victory or defeat, but also how that country faced the victory or defeat. Serious question has to be posed whether that country had a straight-forward victory or defeat on all fronts, or whether there were other circumstantial events that deeply affected each country’s situation. First we need to understand the nature of Soviet defeat. The Cold War was a combination of rivalry based on values and power. But there was no war that became the cause of the fall of the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union disintegrated itself. The reasons of this disintegration are manifolds. But on the whole, since “disintegration” and not “war victory” was the prime cause of Soviet’s fall, the whole event was perceived as the victory of values. This became the major tenet in the general analysis of international politics and victory of power has been considered as the second tenet. As to South Korea, clearly belonging to the victor’s side, the predominance of liberal values was conspicuous by several additional factors. The victory of democracy 1 was not a gift from the change of international politics but a result which people of Korea gained through their painful fight against military dictatorship. The democratic victory of South Korea contrasted high with the failure of North Korea, which became one of the most undemocratic countries of the world. South Korea’s rise was certainly not disconnected with its rise of power, but the predominant theme for South Korea was the strength of liberal values. Coming to Japan, however, shared feeling of liberal-democracy’s victory did not take place. Since Japan was perhaps the most successful show case of economic rise based on market economy and democratic system starting from its defeat at WWII, this absence of the feeling of victory is conspicuous. Two domestic situations, explosion of bubble in 1991 resulting in unprecedented economic difficulty that left no room for enjoying the benefit of market economy, and failure of political reform in 1993-94 under Ichiro Ozawa who aimed a creation of two-party system are a reason for this complacency. But perhaps the most indicative factor that surrounded Japan was Japan’s so called “defeat at the First Gulf War 1990-91” due to its excessive passive pacifism. Overcoming this “defeat” became Japan’s major foreign policy agenda and realism was the most important factor there. Thus realism, and not liberalism, became its major vehicle of international politics. In the vanquished side, the Soviet Union became the looser of the Cold War. It had the straight-forward defeat, which resulted in halving its population and losing a quarter of the territory. But this defeat resulted in the creation of a new state called the Russian Federation. Thus exaltation of victory of the Russian Federation, represented by Yeltsin, against the falling Soviet Union, symbolized by Gorbachev became the major tenet and bitterness of defeat became only the sub-tenet of the decade. Thus, the victory of values, i.e. democracy and market economy, were hailed even more strongly in Russia than in the United States in the initial months, if not years, under President Yeltsin. But the policy of reform, which identified Russia with democracy and market values, soon got its backlash. Nevertheless, the Yeltsin era which lasted until the very end of 1999 should be remembered as an era of reform when values which can be loosely framed as liberal-democracy was the major tenet in running the society and international politics. The way China faced this situation was much more complex. In terms of the Cold War structure, China was a country rivaling the Soviet Union within the Socialist block. Since the rivalry with the Soviet Union was a more predominant factor than the global East-West rivalry except the very initial years, the demise of the Soviet Union did not mean at all for China sharing the same bitterness of defeat. Quite to the contrary, Den Xiaoping, who was almost a decade ahead in his reform policy of “Reform and 2 Opening” than Gorbachev’s “Perestroika”, was watching very closely the situation developing in Russia. This resulted in the 1989 Tiananmen Square Incident and this incident dictated Chinese policy over the 1990’s, and key factor was to restrict the area of liberal reforms exclusively in the economic area based on greater freedom of activities, but strictly monopolizing political power within the auspices of the Communist Party of China (CPC). Thus realism and not liberalism became the predominant tenet of the decade for China. Unlike the Korean case, Taiwan’s success for democratization could have become another factor making cautious to political liberalism. Constructivist thinking, or identity pursuit became another factor for the decision making process of the five countries. But in any country it took the leading tenet of the decade like liberalism in case of the U.S., South Korea and Russia or realism in case of Japan and China. The role of constructivist thinking varied in each country depending on the specific circumstance which surrounded each one. Perhaps it has occupied the position of the second tenet in Korea (as search for unification with the North) and Japan (as its pursuit for the reconciliation with Asia). In case of Russia, since the backlash against liberal reforms was first-of-all reflected in realist power thinking, constructivist factor, though important, may best be placed as a third factor (as its pursuit for Russian identity). In case of the United States, values and power that made the U.S. were almost identical with American identity, so in that sense there was no room for bringing in constructivist identity thinking. In case of China, “keep your profile low” was the major tenet of realism and China’s identity thinking has not appeared on the surface. Thus in terms of the international relations theory, this paper does not take an approach of viewing the world with a single tenet, either liberalism, realism or constructivism. It takes an eclectic approach of looking into the process of decision making of each country from liberal, realist and constructivist approaches and evaluate which factor has played the major, second, or third, or practically very little role in each country. Table 1: East Asia and International Relations Theory in the 1990’s America South Korea Japan Russia China Values (Liberalism) Major tenet Major tenet Third tenet Major tenet Second tenet Power Second Third tenet Major tenet Second Major tenet 3 (Realism) tenet Identity ----(Constructivism) tenet Second tenet Second tenet Third Tenet ----- The United States Historian might argue when did the Cold War end? This paper argues that we can define the years from 1989, when the Berlin wall fell and Bush–Gorbachev meeting in Malta declared the end of the Cold War, till 1991, when the Soviet Union disintegrated and the Russian Federation was created, as the period which marked the end of the Cold War. Why did the Cold War end? On the one hand, the disintegration of the Soviet system came from the fact that Soviet system could not achieve the dynamism which its society required. That failure was largely due to the defect of socialist-Marxist values/ideologies which were the basis of the society. It could also be understood by Soviets’ failure in power-politics, such as its disastrous entry into the war in Afghanistan, combined with Reagan’s successful power politics to squeeze the Soviets with the Strategic Defense Initiatives (SDI). So it is clear that both the elements of values/ideology and of power politics played an important role for the demise of the Soviet Uniuon. But because the major factor which propelled the fall of the Soviet Union was its “disintegration” from within its society and not “defeat” from the power struggle with outside forces, the end of the Cold War is generally perceived in the United States, which clearly emerged as its victor, and elsewhere in the world, that the prevailing factor which led this victory was values/ ideology which can loosely be defined as the victory of liberal- democracy. Thus liberalism can be considered as the major tenet to gauge the era in the United States. Francis Fukuyama’s “The End of History and the Last Man” was perhaps the most representative analysis from that perspective. In reality the major part of the 1990’s for the United States under President Clinton 1993-2000 was very far from the end of the history. Despites overwhelming victory of liberal democracy, the world moved into an era of hot wars from cold war. The most symbolic war that took place was the Gulf War of 1990-91, and successive wars that took place in former Yugoslavia most importantly at Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina and Kosovo from 1991 till 1999. But looking these events from the perspectives of values and power, it is clear that a strong push came from the perspectives that certain right of minor states for independence has to be respected against strong powers which wanted to dominate them. Such was the case of Kuwait against powerful Iraq under Saddam 4 Hussein, and cases in Yugoslavia, smaller ethnic minorities fighting their independence against Serbia, the most powerful ethnic group of former Yugoslavia. In another case, alleged atrocities committed by one powerful group became casus belli for intervention under the new values of humanitarian intervention, the most representative case being NATO’s intervention into the Kosovo war. Admittedly real politics and power balance were inseparable in these new wars. Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait cannot be dissociated with such issues as who control the oil or whose power will become predominant in the Middle East. Wars in former Yugoslavia cannot be dissociated with such factors that historically and geopolitically Serbia was the closest to Russia and some other groups such as Croatia or Bosnia-Herzegovina more supported by Germany and other European states. Nevertheless a strong tenant of fundamental values such as minority’s right or humanitarian consideration was the leading factor in international politics. The question of war and peace was more or less the same in East Asia. The difference was that unlike the Middle East or Yugoslavia hot war were avoided in East Asia. But the logic of U.S. intervention to the potential military conflicts was very much the same. The first real crisis took place in 1993-94 around North Korea’s intention to hold nuclear weapons. North Korea by then was the most oppressive, undemocratic and failed state in East Asia and this country holding nuclear weapons was impermissible. The evilness of the system based on value-judgment became the leading factor for the U.S. not to allow North Korea to hold nuclear weapons. It goes without saying that whole change of power balance and possible security threat to the United States, if not immediate but in future, was a combined tenet of U.S. thinking, but these realists thinking were underlying factors rather than frontal factors. The second crisis took place at Taiwan Strait in 1995-96, and the value of democracy was probably even more apparent than the North Korean case. Here the focal point was Taiwan which became the stunning example of success in the strenuous efforts toward democratization. The rise of Lee Denhui, a Taiwan born citizen under Japanese occupation from within Kuomintang and his eventual seizure of power in 1988 and rising to the position of the president in 1990, preparing its way to a democratically elected president in 1996 was a spectacular process of democratization in East Asia. Since democratization meant a natural process of Taiwanization, and the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), whose officially declared objective was to achieve independence, was waiting to win over Kuomintang in a not too distant future, China’s concern on free democratic election was rising high. Cross strait missile launching exercises that took place in 1995-96 reflected well that concern and the sending of 5 American aircraft career to the vicinity of the Strait reflected strong American concern that the democratic process that began in Taiwan should not be stopped. It has naturally realist concern to curb China’s expansive influence in East Asia, but likewise North Korean cases, these realists thinking were underlying factors rather than frontal factors. South Korea South Korea was a member of the capitalist block in East Asia, thus naturally belongs to the club of winners after the end of the Cold War. But South Korean victory should be looked at much more from the perspectives of its own process of democratization rather than an outcome of the changes that happened in the Soviet Union. Post-war Korea after Japan’s defeat and liberation from its occupation suffered from two unexpected turmoil: divided occupation and the Korean War. South Korea that was formulated became a country governed by Lee’s dictatorship succeeded by decades of military dictatorship under three military-presidents. But social friction under military dictatorship reached to its height by students’ movement after President Park’s assassination in 1979 leading to President Chun Doo-hwan’s Kwangju massacre in 1982. President Roh Tae-Woo’s assumption of power in 1988 was conditioned by his Declaration of Democratization of June 29, 1987. Thus President Roh became the last president selected from the military, and a full democratic election took place thence onwards to elect civilian presidents. Thus the two non-military candidates who run unsuccessfully for the election in 1972 first President Kim Young-sam 1993-97 and President Kim Dae-Jung 1998-2002 were successively elected in the 1990’s. In this amazing process for strengthening its democracy, South Korea marked series of diplomatic successes which could symbolize the power of democracy and market-economy. Under President Roh Tae-woo it held successfully the 1988 Olympics game. President Roh continued to make a staggering diplomatic success at the end of the Cold War by way of opening diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union in 1990 and with China in 1992. Under President Kim Young-sam South Korea joined the OECD in 1996, as the second country from Asia following Japan. When the Asian financial crisis struck South Korea in 1997-98, one of the achievements made by President Kim Dae-jun was to follow strictly IMF’s rigorous policy of economic reform which became a key factor to strengthen Korean economic performance thence onwards. Kim’s policy to enter into various type of partnerships with its surrounding countries in 1998 and 1999 can also be considered as reflecting the quality of Korea’s development, so should also be considered his initiative to take the leadership role of East Asian regionalism. 6 In considering Korean policy of this period, there is one more factor, which played a critical role in shaping its strategic objectives. That is Korean search for its identity, in concrete terms its pursuit of final unification. It is difficult to theorize the problem of unification either from the point of view of liberal values or from the point of view of realist power consideration. Unification is best explained as identity consciousness of the Korean people. Immediately after the end of the Cold War under President Roh Tae-woo, a surge of several activities took place. The first leaders’ meeting after the divide at prime-ministers level took place in September 1990 and thenceforward the eight rounds of talks resulted in “Agreement concerning the Reconciliation, Nonaggression, Exchanges and Cooperation between the South and the North” in December 1991 and “Joint Declaration concerning Denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula” in February 1992. The North and the South joined the United Nations simultaneously in September 1991. This heightened mood for rapprochement cooled off considerably by the 1993-94 North Korean attempts to hold nuclear weapons, and by Kim Young-sam’s inability to cope with the situation leaving the role of key actor to the United States. But a surge of identity search took place under President Kim Dae-jung in his sunshine policy which resulted into the June 2000 North-South Summit which has ever taken place after the split between the two Koreas. The 2000 North-South Summit and Kim Dae-jung’s pursuit of sunshine policy may remain in the history as his greatest achievement. One may argue that since North Korea has one of the worst records on its democracy, there is an inherent tension on Korean zeal for democracy creation and its search for unification. Naturally the success of Korean foreign policy cannot just be considered as the result of pursuit of liberal values or constructivist values of unification. Pursuit of Korean power underpins all pursuit of above-mentioned goals. But in relations to the liberal values, we do not see some fundamental contradiction between liberal and realist values. But in relations to North Korea, because North Korea became one of the harshest military states which increasingly is basing its security on nuclear weapons, South Korean unification policy as was labeled as Sunshine Policy in this decade, could meet to some fundamental contradiction. Japan As the result of the end of the Cold War, Japan should have appeared as the second victor next to the United States. Japan’s economic might as was perceived at the end of the 1980’s made this country even the greatest threat for the United States after the end 7 of the Cold War. But interestingly, the 1990’s did not bring about that feeling of victory in Japan. The first reason is probably due to the fact that the two fundamental powers which made Japan’s economic might somehow started to dysfunction after the end of the Cold War. Japan’s capitalist economy faced an unprecedented strife by the explosion of the bubble economy in 1991 and the whole 90’s remained as the decade of economic stagnation. The political reform that started in 1993 aiming to create a two-party system under the initiative of Ichiro Ozawa proved to be short-lived, and the LDP regained some power as early as in 1994 and full power in 1996. The fall of authority of the Ministry of Finance by political scandal weakened bureaucracy, one of the foundations of post-war Japan’s economic successes. All these did not crown Japan with success and victory at the wake of the Cold War. The second reason is probably due to what we usually call “Japan’s defeat of 1991” at the first Gulf War. When Saddam Hussein attacked Kuwait in August 1990, Japan’s long-time engrained passive pacifism prevented to act effectively. Initial reactions proved to be effective, but overall economic assistance, which rose to 1.4 billion grant assistance was labeled as “too little and too late.” The parliamentary debate to discuss a bill to send the SDF for non-combat activities in the fall of 1990 collapsed due to the inability of the government officials to adequately explain why this troop could legally be sent under the Article 9 of the Constitution. When the government of Kuwait made a full page message to thank the nations that helped liberating it from Hussein’s invasion, Japan’s name was not included in it. The inability of act effectively at the first Gulf war thus became a national humiliation, particularly among policy makers and defense-security related officials. How to act more responsibly on issues related to war and peace and how to overcome Japan’s lost confidence in the United States and other international community became Japan’s major theme of foreign policy. Liberalism thus lost ground in Japan to dominate its strategic thinking in the 1990’s. It occupies only the third tenet in Japan’s strategic thinking. Realism instead, or as Mike Green defined famously, “Reluctant Realism” became Japan’s major tenet of the 1990’s. Three more issues surrounding Japan’s defense–security environment in the middle of the 1990’s gave further push toward Japan’s realism. First, the North-Korean nuclear crisis in 1993-94 made U.S. and Japan’s defense and security experts realize that if in case the worst happens in the Peninsula between the United States and North Korea, Japanese SDF may even not be in a position of assisting US troops for their rear area support due to the lack of necessary legislation. Second, in September 1995 a primary school girl was raped by an American soldier in Okinawa. Okinawa’s public opinion 8 exploded and concrete measures needed to be introduced to remedy the relationship. Third, the Taiwan missile crisis of 1995-96 shook Japan to realize how the situation across the Taiwan Strait could be precarious. Thus in 1994 the International Peace Cooperation Law was adopted and Japan began sending SDF troops to U.N. Peacekeeping missions. Participation to U.N. Cambodian mission in 1994 became a break-through event. The Okinawa incident resulted in the establishment of the Special Action Committee on Facilities and Areas in Okinawa (SACO) in November 95, and the December 1996 SACO agreement drew conclusion to relocate the Futenma Base from the position where it was currently located. The North Korean crisis combined with rising tension at the Taiwan Strait resulted in the overall reassessment of the alliance, and in April 1996, upon the visit of President Clinton to Japan, “The Japan-US Joint Declaration on Security-Alliance for the 21st Century” was adopted. Based on this Joint Declaration, the new Guidelines for Defense Cooperation were adopted in September 1997. In order to enable these Guidelines to work within Japanese domestic legal structure, the Law Concerning Measures to Ensure Peace and Security of Japan in Situations in Areas Surrounding Japan” was adopted in May 1999. On a completely different tenet, on Russia, Japan’s slowness in grasping realist opportunity failed to resolve the disputed territorial issues with Russia in its 1991-92 historic opportunity, but its realization of realist need to strengthen ties with Russia brought the two countries very close in 1997-98. Unfortunately the two sides failed to grasp this opportunity either. As the realist thread became the first tenet of Japanese political thinking in the 1990’s, perhaps we need to explain Japan’s reconciliation with Asia, and notably with China and Korea, by constructivist thinking, which may be the second tenet of this decade. The first half the 1990’s were crowned with several distinctive successes from that perspective. In October 1992 the Emperor Akihito visited Beijing for the first time after the end of the WWII. Perhaps as seen below, from China’s perspective the invitation was made largely from realist perspective to bring China’s position back to the international fora after the Tiananmen Square incident in 1989. But from Japan’s perspective, this was a decisive action for the reconciliation. In relations to Korea, comfort women issue was brought to the center of the relationship at the end of President Roh Tae-woo towards the first years under President Kim Young-sam. Kono Statement was issued in 1993 and based on that statement the Asian Women Fund was 9 established in 1995. As if to synthesize all these actions for reconciliation Prime Minister Tomiichi Murayama’s Statement, the most decisive statement of apology ever pronounced in Japan and probably in the world, was pronounced in August 1995. There was a certain feeling in Japan that this statement may mark “the end of history” with Asia. China’s reaction under Jiang Zemin soon proved to be that reconciliation is still a long-term objective, but Kim Dae-jun’s visit in October 1998 marked the height of post WWII Japan-Korea reconciliation. Even Jiang Zemin’s visit in November 1998, much criticized in Japan for his “preaching” about Japan’s need for further apology, adopted a Joint Declaration which underlined the need for future-oriented relations. Prime Minister Obuchi’s encouragement in the course of 1999 to let China join the WTO was also considered as continued policy of reconciliation with China In 1999 Obuchi’s endeavor for reconciliation was also embodied in his initiative to hold Japan-China-South Korea summit meeting within the auspices of ASEAN Plus Three (APT) meeting that started in 1997. Russia The disintegration of the Soviet Union is a subject which needs to have a full scope analysis: the formation of the Soviet Union, its development and its fall. This is a task outside the scope of this paper, but a few words on Gorbachev’s policy of Perestroika is necessary because that policy triggered the end of the Cold War. The Russian word Perestroika is constructed with two parts: “pere---” means “re---” and “stroika” means “construction”. It meant “reconstruction” of socialism. Gorbachev saw stagnation zastoi in the Soviet society, so he decided to “reconstruct” socialism and wipe out that stagnation. The key factor he wanted to introduce was human factors. He introduced glasnostj which meant transparency. In real terms this meant mobilization of intellectual thinking and debates to bring in ideas and proposals for changes. One of Perestroika’s definitions was “Socialism with Human Face”. So things began from political shaking, and this shaking was believed to introduce effective economic changes. Activated economic policy should have brought a strengthened socialist system. In that sense, Gorbachev’s policy was profoundly liberal, in his belief in the system of socialism and in his belief in the good nature of human beings. In reality, things turned around into complete opposite direction. Free debates based on Glasnostj brought about hundreds of ideas on political and economic reforms, but it first of all brought about total economic confusion. Then Gorbachev’s belief in delegation of power from the Communist Party 10 of the Soviet Union (CPSU) to a presidential system under the notion of liberal socialism resulted in the disintegration of the Soviet Union, triggered by the minority ethnic rights for independence. For those who have observed the Soviet Union and argued that the concentration of power to the CPSU and its autocratic political and economic policy may sometimes lead into its disintegration, the peaceful transfer of power from the Soviet Union to the Russian Federation was almost a miracle. The alchemy to transform Soviet defeat into Russian victory could only be explained by the extraordinary power relationship between Gorbachev and Yeltsin. Yeltsin’s rise to power in that sense has a critical importance. Born in 1931, first became a construction engineer at Sverdlovsk, entered the CPSU in 1961, became full time party apparatchik in 1968 and member of the Central Committee in 1981. After Gorbachev’s rise in 1985, Yeltsin first became a strong supporter of Perestroika, but in 1987, his radical reform lines went into collision first with CPSU conservatives and then with Gorbachev himself and Yeltsin resigned the post of Politburo in November, known to have become a radical reformer. Yeltsin made his comeback, in March 1989 to the Congress of People’s Deputies of the Soviet Union, and then in April 1900 to the Congress of People’s Deputies of Russia, finally to the Chairmen of that Congress in May of that year. Yeltsin’s political instinct to gather reformists’ power in the Russian Federation, to crush the conservatives as well as Gorbachev’s supporters after the August 1991 Coup, to dissolve the Soviet Union and to oust Gorbachev through friendly parting with other republics, starting with Ukraine and Kazakhsan in December 1991, and finally to realize the creation of an autonomous Russian power was simply amazing. That Russian Federation incarnated the principle of reform based on democratic system and market economy. It was an art of real political genius. In contrast to Gorbachev, whose realist political instinct was so weak that it led only to the demise of his own position, Yeltin’s realist instinct for power lead him stronger step by step, finally leading to the President of the Russian Federation. But at the same time, what is conspicuous in Yeltsin was that from the time he became Gorbachev’s perestroika supporter and then strong critique of Ligachev and other conservative CPSU members, he supported liberal values to make Russia a democratic country. With his realist instinct, Yeltsin was never indifferent with his power position. But his policy as the President of the Russian Federation has always been geared to liberal values. There are distinctively two periods within Yeltsin’s presidency, when his liberal policy direction was shown most vividly. The first period is from December 1991 till October 1993, when his initial policy of economic reform was implemented under the 11 guidance of Prime Minister Guidar. The initial year of its foreign policy could be defined as the year of Atlanticism, when Russia’as attention was directed to major Western countries, including the United States, Europe and Japan. In Asia, Japan became the representative of Western values, embodying the success of market economy and democracy. Russia-Japan relations then saw a historic opportunity for a break through. But this short-lived period of Atlanticism is dabbed as the period of euphoria. Guidar’s radical economic policy created a hyper-inflation and economic turmoil, resulting in arms conflicts with his opponents in October 1993. When this bitter conflict ended with Yeltin’s bloody victory, Yeltsin sought to implement a policy of social harmony and gradual economic reform, and through this “appeasement policy” successfully won the election for his second presidency in July 1996. But due his health problem he stayed out from politics until March 1997. Meanwhile, in the area of foreign policy, the age of Atlanticism was over, and Kremlin began to shed greater attention to the Eurasian Continent, first of all to former Soviet Republics, and then to Asia, notably in improving relations with China and also with South Korea. Yeltins’ physical recovery and re-appearance in Russian domestic and external politics in March 1997 revived for about a year the vigor of initial year of reform period. The implementation of foreign policy was assisted by Yefgeny Primakov as foreign minister from January 1996 till September 98. Yeltsin’s attention to Japan rose again during this period symbolized by the meetings with Prime Minister Ryutaro Hashimoto in Krasnoyarsk in November 1997 and in Kawana in April 1998. This time Yeltsin’s interest to Japan has a stronger geo-political connotation. It could be understood as a continuation of Eurasianism particularly in responding to NATO’s eastward expansion. NATO decided, in summer 1997 to invite Poland, Hungary and Czech to become its member and the actual enlargement took place in March 1999. Yeltsin’s foreign policy which wavered in this period from Atlanticism to Eurasianism cannot be separated from his thinking on identity. Right from the period of Peter the Great, Westerners or Slavophiles is the key issue which haunted all Russian intellectuals to this day. The present–day debate between Slavophiles and Westerners is taking place in the geographic form of Atlanticism and Euracianism. But this shift from Atlanticism to Eurasianism can be better understood first from realist power consideration and then from constructivist identity point of view. China 12 The way China faced the end of the Cold War in 1989 was very different from the way the Soviet Union saw its defeat. In case of the Soviet Union the socialist system which sustained the nation collapsed and Russian Federation decided, at least for a certain period, to create a nation with totally different values and system. China’s case was very different. China’s reform had already started in 1978 under Deng Xiaoping’s policy of “Reform and Opening”. The structure was very clear. Introduce a capitalist oriented economy based on market mechanism, but keep CPC’s political power intact. One may attribute the former as economic liberalism and the latter as realist power consideration. But China’s failure erupted on June 4 1989 at the Tiananmen Square when harmonious development of economic liberalism and political realism completely broke. Deng’s decision was to keep the ascendency of political realism and crush the students who were seeking greater freedom. It goes therefore without saying that the major tenet for China was to base its thinking on realism and ensure that CPC’s power should not be derogated. Relatively tough foreign policy under Jiang Zemin in all fronts can well be explained because of its tense political situation. On Taiwan, the Taiwan Strait Crisis of 1995-96 to engage in series of missile launching exercises in responding to Lee Deng-hui’s initiative to hold direct presidential election is the first example. Tough policy of rebuking Japan on historical memory issues particularly in the latter part of the 1990’s, when the Japanese side has displayed high degree of apology policy in the first half of the 1990’s is the second example. As stated above Jiang Zemin’s 1998 visit to Japan and his policy of preaching Japan to remember and apologize for history is fresh in the memory of the Japanese. China’s sharp criticism against the United States at the bombing of the Chinese Embassy in Belgrade in May 1999 and tense debate on “peace and development” and “US-China Cold War” that developed in this period was another example. As for China’s liberal economic policy, after the Tiananmen Square incident, there emerged certain period of uncertainty. But the renowned visit by Deng Xiaoping to Southern Provinces in 1992 unambiguously established that China’s liberal economy could and shall remain as the decisive pillar of its economic policy. Despites sometimes severed relations with the US, China’s willingness to join the WTO remained basically un-wavered. China’s membership to the WTO was finally approved in November 2001. China’s identity related issues stayed much subdued. After the Tiananmen Square incident, China’s US policy became embodied in 24 words, where “keep your profile low” was the major tenet of realism. For China of the 1990’s, pronouncement of identity was too early and perhaps we need to wait this position for another two decades 13 until the 2010’s. International Relations Theory and Asian reality If one looks at the reality of international politics in East Asia and how policy makers mind could be understood by three theoretical International Relations theory, one can reasonably say that the three frameworks of realism, liberalism and constructivism, if used eclectically, give reasonable ground for understanding what has taken place. The Overview section and all subsequent analyses regarding five countries give reasonable evidence for the successful adaptation of East Asian reality to the theoretical framework. But if one tries to analyze how decision making was made in East Asia and whether decisions made by certain theoretical framework actually produced some outcome, which may meet or not meet the strategic requirement to maximize that country’s national interest, one is left with a real question: would not a better grasping of International Relations theory help implementing a country’s policy more effectively to achieve maximum strategic objective? In case of the United States, one question which occurs immediately is whether the sense of victory of democratic values has not weakened US realist ability to comprehend and adjust its policy to the reality in East Asia. Did the United States sufficiently understand Russia’s need for greater realism after the initial period of Euphoria was over? How much attention was given in the United Sates after the 1989 Tiananmen Square Incident about China’s necessity of shifting to a realist policy of concentrating its political power within the CPC? How much attention was given to Japan in the 1990’s to really appreciate the weight of what was happening there, when its shift to realism was nonetheless slow and when its constructivist reconciliation efforts were obscured by some domestic opposition which caught much of media attention? In case of South Korea, the crux of the matter does not depend on the application of a theory. For policy makers the choice, theoretical and real, is clear. The contradiction between the constructivist urge for national unification on the one hand, and the realist need to ensure its own security and the liberal needs to strengthen democratic values on the other, is deeply engrained in the policy choices among Korean leaders. Retrospectively one may always argue that certain choice at certain period did not hit the optimal balance. But at least that dilemma was cognizant in Korea. 14 So was the dilemma cognizant in Japan. The choice is clear but the situation is so complex and unity of choices do not appear easily. Although I consider the characteristics of this decade as a greater realism and stronger reconciliation efforts with Asia, that direction was taken not without controversy. For some policy makers with realist orientation, the realism introduced in this period was too slow and too reluctant. For other policy makers with pacifist orientation, the change was too harsh and too dangerous. For some policy makers with reconciliation orientation, the Murayama Statement and other measures introduced were a minimum and more efforts are needed to do. For other policy makers reconciliation policy introduced in this decade was too apologetic and harmed the honor of forefathers. These difficult policy choices were there in addition to the difficult policy choices on democratic and economic system. In contrast it seems that Yeltsin’s policy of achieving greater policy with liberal values with his instinct on power politics seemed to have hit a reasonably balanced position. One may naturally argue that his absorption in liberal values, hence his attachment to the Atlanticism in the initial year was theoretically misguided approach. But retrospectively that lasted for one year only and the Eurasianism oriented policy for Russia may best suit Russia’s realist and identity interest. For China, The policy choice is very difficult, likewise in Korea and Japan. But perhaps the policy choice between liberally oriented economic policy based on market economy and realist oriented political policy based on the unification of power under the CPC, is almost impossible to resolve. This may not be an era where the three International Relations theory of three frameworks of International Relations theory is not able to give an adequate answer. One can assume that some constructivist efforts await China to get a breakthrough. (END) 15