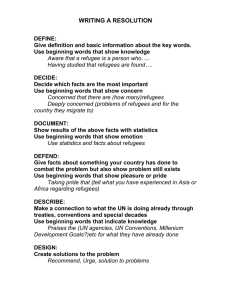

The American University in Cairo

advertisement