The American University in Cairo

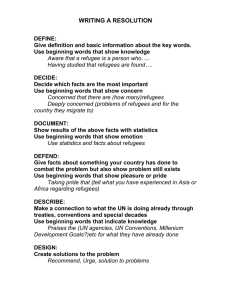

advertisement