Programming in C & Living in Unix

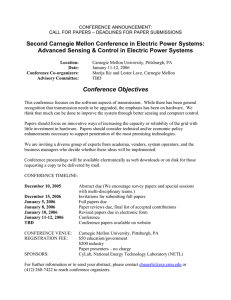

advertisement

Carnegie Mellon

Programming in C & Living in Unix

15-213: Introduction to Computer Systems

Recitation 6: Monday, Sept. 30, 2013

Marjorie Carlson

Section A

1

Carnegie Mellon

Weekly Update

Buffer Lab is due Tuesday (tomorrow), 11:59PM

This is another lab you don’t want to waste your late days on.

Cache Lab is out Tuesday (tomorrow), 11:59 PM

Due Thursday October 10th

Cache Lab has two parts.

Write a 200- to 300-line C program that simulates the

behavior of cache. (Let the coding in C begin!)

2. Optimize a small matrix transpose function in order to

minimize the number of cache misses.

Next recitation will address part 2. For part 1, pay close

attention in class this week.

1.

2

Carnegie Mellon

Agenda

Living in Unix

Beginner

The Command Line

Basic Commands

Pipes & Redirects

Intermediate

More Commands

The Environment

Shell Scripting

Programming in C

Refresher

Compiling

Hunting Memory Bugs

GDB

Valgrind

3

Carnegie Mellon

“In the Beginning was the Command Line…”

Command Line Interface

“Provides a means of communication between a user and a

computer that is based solely on textual input and output.”

Shell

A shell is a program that reads and executes the commands

entered on the command line. It provides “an interface between

the user and the internal parts of the operating system (at the very

core of which is the kernel).”

The original UNIX shell is sh (the Bourne shell).

Many other versions exist: bash, csh, etc.

The Linux Information Project: Shell

The Linux Information Project: Command Line

4

Carnegie Mellon

Unix – Beginner: Basic Commands

Moving Around

Manipulating Files

ls

List directory contents

mv

Move (rename) files

cd

Change working directory

cp

Copy files (and directories with “-r”)

pwd

Display present working directory

rm

Remove files (or directories with “-r”)

ln

Make links between files/directories

cat

Concatenate and print files

mkdir

Make directories

chmod

Change file permission bits

Working Remotely

Looking Up Commands

ssh

Secure remote login program

man

Interface to online reference manuals

sftp

Secure remote file transfer program

which

Shows the full path of shell commands

scp

Secure remote file copy program

locate

Find files by name

Managing Processes

Other Important Commands

ps

Report current processes status

echo

Display a line of text

kill

Terminate a process

exit

Cause the shell to exit

jobs

Report current shell’s job status

history

Display the command history list

fg (bg)

Run jobs in foreground (background) who

Show who is logged on the system

5

Carnegie Mellon

Quick Aside: Using the rm Command

rm ./filename – deletes file “filename” in current dir.

rm ./*ame – deletes all files in the current directory that

end in “ame.”

rm –r ./* – deletes all files and directories inside the

current directory.

rm -r ./directory – deletes all files inside the given

directory and the directory itself.

sudo rm –rvf /* – deletes the entire hard drive.

DO NOT DO THIS!!!

sudo runs the command as root, allowing you to delete anything.

-v (verbose) flag will list all the files being deleted.

-f (force) flag prevents it from asking for confirmation before

deleting important files.

6

Carnegie Mellon

Quick Aside: Man Page Sections

man foo prints the manual page for the foo, where foo is

any user command, system call, C library function, etc.

However, some programs, utilities, and functions have the

same name, so you have to specify which section you want

(e.g., man 3 printf gets you the man page for the C

library function printf, not the Unix command printf).

How do you know which section you want?

whatis foo

man –f foo

man –k foo lists all man pages mentioning “foo.”

7

Carnegie Mellon

Unix – Beginner: Pipes & Redirects

A pipe (|) between two commands sends the first

command’s output to the second command as its input.

A redirect (< or >) does basically the same thing, but with a

file rather than a process as the input or output.

Remember this slide?

Option 1: Pipes

$ cat exploitfile | ./hex2raw | ./bufbomb -t andrewID

Option 2: Redirects

$ ./hex2raw < exploitfile > exploit-rawfile

$ ./bufbomb -t andrewID < exploit-rawfile

8

Carnegie Mellon

Agenda

Living in Unix

Beginner

The Command Line

Basic Commands

Pipes & Redirects

Intermediate

More Commands

The Environment

Shell Scripting

Programming in C

Refresher

Compiling

Hunting Memory Bugs

GDB

Valgrind

9

Carnegie Mellon

Unix – Intermediate: More Commands

Transforming Text

Useful with Other Commands

cut

Remove sections from each line of screen

files (or redirected text)

Screen manager with terminal

emulation

sed

Stream editor for filtering and

transforming text

sudo

Execute a command as another user

(typically root)

tr

Translate or delete characters

sleep

Delay for a specified amount of time

Archiving

Looking Up Commands

zip

Package and compress files

alias

Define or display aliases

tar

Tar file creation, extraction and

manipulation

export

(setenv)*

Exposes variables to the shell

environment and its following

commands

Manipulating File Attributes

Searching Files and File Content

touch

Change file timestamps (creates

empty file, if nonexistent)

find

Search for files in a directory hierarchy

umask

Set file mode creation mask

grep

Print lines matching a pattern

* – Bash uses export. Csh uses setenv.

10

Carnegie Mellon

Unix – Intermediate: Environment Variables

Your shell’s environment is a set of variables, including

information such as your username, your home directory,

even your language.

env lists all your environment variables.

echo $VARIABLENAME prints a specific one.

$PATH is a colon-delimited list of directories to search for

executables.

Variables can be set in config files like .login or

.bashrc, or by scripts, in which case the script must use

export (bash) or setenv (csh) to export changes to the

scope of the shell.

11

Carnegie Mellon

Unix – Intermediate: Shell Scripting

Shell scripting is a powerful tool that lets you integrate

command line tools quickly and easily to solve complex

problems.

Shell scripts are written in a very simple, interpreted

language. The simplest shells scripts are simply a list of

commands to execute.

Shell scripting syntax is not at all user-friendly, but shell

scripting remains popular for its real power.

Teaching shell scripting is depth is beyond the scope of this

course – for more information, check out Kesden’s old 15123 lectures 3, 4 and 5.

12

Carnegie Mellon

Unix – Intermediate: Shell Scripting

To write a shell script:

Open your preferred editor.

Type #!/bin/sh. When you run the script, this will tell the

OS that what follows is a shell script.

Write the relevant commands.

Save the file. (You may want its extension to be .sh.)

Right now it’s just a text file – not an executable. You need to

chmod +x foo.sh it to make it executable.

Now run it as ./foo.sh!

13

Carnegie Mellon

Unix – Intermediate: Shell Scripting

hello.sh

hello.sh with variables

#!/bin/sh

#!/bin/sh

# Prints “Hello, world.” to STDOUT

echo “Hello, world.”

str=“Hello, world.”

echo $str # Also prints “Hello, world.”

Anything after a ‘#’ is a comment.

Variables

Setting a variable takes the form ‘varName=VALUE’.

There CANNOT be any spaces to the left and right of the “=“.

Evaluating a variable takes the form “$varName”.

Shell scripting is syntactically subtle. (Unquoted strings,

“quoted strings”, ‘single-quoted strings’ and `back quotes`

all mean different things!)

14

Carnegie Mellon

Agenda

Living in Unix

Beginner

The Command Line

Basic Commands

Pipes & Redirects

Intermediate

More Commands

The Environment

Shell Scripting

Programming in C

Refresher

Compiling

Hunting Memory Bugs

GDB

Valgrind

15

Carnegie Mellon

C – Refresher: Things to Remember

If you allocate it, free it.

int *array= malloc(5 * sizeof(int));

…

free(array);

If you use Standard C Library functions that involve

pointers, make sure you know if you need to free it. (This

will be relevant in proxylab.)

16

Carnegie Mellon

C – Refresher: Things to Remember

There is no String type. Strings are just NULL-terminated

char arrays.

Setting pointers to NULL after freeing them is a good habit,

so is checking if they are equal to NULL.

Global variables are evil, but if you must use make sure you

use extern where appropriate.

Define functions with prototypes, preferably in a header

file, for simplicity and clarity.

17

Carnegie Mellon

C – Refresher: Command Line Arguments

If you want to pass arguments on the command line to

your C functions, your main function’s parameters must be

int main(int argc, char **argv)

argc is the number of arguments. (Always ≥ 1)

argv is an array of char*s (more or less an array of

strings) corresponding to the command line input.

argv[0] is always the name of the program.

The rest of the array are the arguments, parsed on

space.

18

Carnegie Mellon

C – Refresher: Command Line Arguments

$ ls –l private

argc = 3

argv = {“ls”, “-l”, “etc”}

19

Carnegie Mellon

C – Refresher: Headers & Libraries

Header files make your

functions available to other

source files.

Implementation in .c, and

declarations in .h.

forward declarations

struct prototypes

#defines

It should be wrapped in

#ifndef LINKEDLIST_H

#define LINKEDLIST_H

...

#endif

int bitNor(int, int);

int test_bitNor(int, int);

int isNotEqual(int, int);

int test_isNotEqual(int, int);

int anyOddBit();

int test_anyOddBit();

int rotateLeft(int, int);

int test_rotateLeft(int, int);

int bitParity(int);

int test_bitParity(int);

int tmin();

int test_tmin();

int fitsBits(int, int);

int test_fitsBits(int, int);

int rempwr2(int, int);

int test_rempwr2(int, int);

int addOK(int, int);

int test_addOK(int, int);

int isNonZero(int);

int test_isNonZero(int);

int ilog2(int);

int test_ilog2(int);

unsigned float_half(unsigned);

unsigned test_float_half(unsigned);

unsigned float_twice(unsigned);

unsigned test_float_twice(unsignned);

bits.h

20

Carnegie Mellon

C – Refresher: Headers & Libraries

#include <*.h> - Used for including header files found

in the C include path: standard C libraries.

#include “*.h” – Used for including header files in the

same directory.

There are command-line compiler flags to control where

header files are searched for, but you shouldn’t need to

worry about that.

21

Carnegie Mellon

C – Refresher: “Reverse” Demo

reverse takes arguments from the command line and

prints each of them backwards.

It calls reverse_strdup.

To compile:

gcc –Wall –reverse.c –reverse_strdup.c –o reverse

22

Carnegie Mellon

Agenda

Living in Unix

Beginner

The Command Line

Basic Commands

Pipes & Redirects

Intermediate

More Commands

The Environment

Shell Scripting

Programming in C

Refresher

Compiling

Hunting Memory Bugs

GDB

Valgrind

23

Carnegie Mellon

C – Compiling: Command Line

gcc

GNU project C and C++ compiler

When compiling C code, all dependencies must be

specified.

Remember how we just compiled?

gcc –Wall –reverse.c –reverse_strdup.c –o reverse

This will not compile:

gcc –Wall –reverse.c –o reverse

24

Carnegie Mellon

C – Compiling: Command Line

gcc

GNU project C and C++ compiler

gcc does not requires these flags, but they encourage

people to write better C code.

Useful Flags

-Wall

Enables all construction warnings

-Wextra

Enables even more warnings not enabled by Wall

-Werror

Treat all warnings as Errors

-pedantic

Issue all mandatory diagnostics listed in C standard

-ansi

Compiles code according to 1989 C standards

-g

Produces debug information (GDB uses this information)

-O1

Optimize

-O2

Optimize even more

-o filename

Names output binary file “filename”

25

Carnegie Mellon

C – Compiling: Makefiles

Make

GNU make utility to maintain groups of programs

Projects can get very complicated very fast, and it can take

a long time to have GCC recompile the whole project for a

small change.

Makefiles are designed to solve this problem; make

recompiles only the parts of the project that have changed

and links them to those that haven’t changed.

Makefiles commonly separate compilation (.c .o) and

linking (.o’s executable).

26

Carnegie Mellon

C – Compiling: Makefiles

Make

GNU make utility to maintain groups of programs

Makefiles consist of one or more rules in the following

form.

Makefile Rule Format

target : source(s)

[TAB]command

[TAB]command

Makefile for “gcc foo.c bar.c baz.c –o myapp”

myapp: foo.o bar.o baz.o

gcc foo.o bar.o baz.o –o myapp

foo.o: foo.c foo.h

gcc –c foo.c

bar.o: bar.c bar.h

gcc –c bar.c

baz.o: baz.c baz.h

gcc –c baz.c

27

Carnegie Mellon

C – Compiling: Makefiles

Make

GNU make utility to maintain groups of programs

Comments are any line beginning with ‘#’

The first line of each command must be a TAB.

If you want help identifying dependencies, you can try:

gcc –MM foo.c outputs foo’s dependencies to the console.

makedepend adds dependencies to the Makefile for you, if you

already have one. E.g., foo.c bar.c baz.c .

28

Carnegie Mellon

C – Compiling: Makefiles

Make

GNU make utility to maintain groups of programs

Use macros – similar to shell variables – to avoid retyping

the same stuff for every .o file.

Makefile Rule Format

CC = gcc

CCOPT = -g –DDEBUG –DPRINT

#CCOPT = -02

foo.o: foo.c foo.h

$(CC) $(CCOPT) –c foo.c

For more information on Makefiles, check out Kesden’s old

15-123 lecture 16.

29

Carnegie Mellon

Agenda

Living in Unix

Beginner

The Command Line

Basic Commands

Pipes & Redirects

Intermediate

More Commands

The Environment

Shell Scripting

Programming in C

Refresher

Compiling

Hunting Memory Bugs

GDB

Valgrind

30

Carnegie Mellon

C – Hunting Memory Bugs: GDB

Useful for debugging the occasional easy segfault (among

other things!).

You’re used to using disas and stepi/nexti to look at

and step through Assembly.

If you compile with –g, you can use list and step/next

to look at and step through the C, too.

This even works after you’ve segfaulted!

Other useful commands:

where (print function stack and lines)

up/down (traverse the function stack)

display/print variables (like you do now with registers).

31

Carnegie Mellon

C – Hunting Memory Bugs: Valgrind

valgrind

A suite of tools for debugging and profiling programs

Great for finding memory problems in C programs. Has a

ton of tools: memcheck, leakfind, cachegrind.

Valgrind’s memcheck tool can:

Track memory leaks & (definitely/possibly) lost blocks

Track origin for uninitialized values

Tell you what line of code seems to have been the problem

Syntax (including the verbose flag):

valgrind --tool=memcheck -v ./myprogram args

valgrind –-tool=leak-check=full -v ./myprogram args

32

Carnegie Mellon

Sources and Useful Links

The Linux Information Project: Command Line Definition

Introduction to Linux: A Hands-On Guide (Garrels)

You should be comfortable with chapters 2, 3, 4 and 5.

The On-line Manual Database

Kesden’s 15-213: Effective Programming in C and Unix

Lectures 3, 4 and 5 cover the basics of Shell Scripting.

Lecture 16 covers Makefiles and lecture 15 covers Valgrind.

33