13 Century Timelines Episode Three: Century of the Stirrup (1200-1300)

advertisement

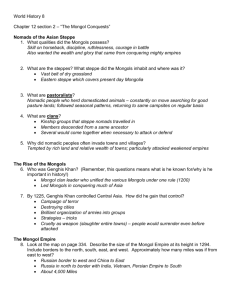

13th Century Timelines Episode Three: Century of the Stirrup (1200-1300) http://www.cnn.com/SPECIALS/1999 /millennium/learning/timelines/ The Larger Thirteenth-Century World Context The larger thirteenth-century world was completely transformed by the Mongols, and, in the process, the Mongols were themselves transformed. On the broad pages of Eurasian history, the thirteenth century was the Golden Age of the pastoral nomad; but it was also the beginning of the end of steppe culture. The thirteenth century was noteworthy as a century of wide-ranging cultural transmission and exchange. The Golden Age of Pastoral Nomads Unlike hunting and gathering societies, pastoral nomads depended on domesticated animals for their livelihood. They herded animals from pasture to pasture in a yearly pattern that varied in response to the availability of water and the prospect of good grassland. Limited resources kept social groups small. And fierce competition among clans and tribes for limited pasture land led to shifting alliances, skirmishes, arranged marriages between clans, and frequent wars punctuated by brief periods of peaceful co-existence. Even a slight unfavorable change in the climate could intensify competition for grazing land. The Golden Age of Pastoral Nomads Genghis Khan's great accomplishment was uniting these competing groups into one military system. Before Genghis Khan, the Mongols were a relatively fragmented pastoral people, loosely organized into competing clans and tribes. Genghis established a chain of command with soldiers organized into groups from ten to ten thousand. Able commanders were promoted on the basis of merit rather than clan allegiance. One of the results of Genghis Khan's successes was that the members of conquered tribes, like the Turks, would sometimes join the Mongol army. Mongol conquests reached further than those of any previous nomadic empire. The Golden Age of Pastoral Nomads Usually history is written by the victors but the Mongols had not developed a writing system. Literate victims of the Mongol conquest shaped our understanding of this period through their bitter stories of brutality and terror. Their stories created the characterization of Mongols as barbarians that has lasted for generations. Eurasian Cultural Diffusion Following each Mongol conquest, small numbers of Mongols were left to administer vast expanses of lands and peoples. The resulting peace opened Central Asia to travel, as Mongols encouraged the expanding trade by land and sea to insure the steady flow of tribute. The consequences were enormous. Like gossip, commercial practices, music, religious teachings, and technical and engineering knowledge passed from East to West and back again. Eurasian Cultural Diffusion Innovations established in one location soon became common practice in others. Such innovations did not only move in one direction, from more technologically advanced urban cultures to less sophisticated nomads. Instead, nomads changed "civilizations" as surely as "civilizations" changed nomads. The stirrup invented between the third and fourth centuries - was exploited by horse riders in Eurasia and Africa. Eurasian Cultural Diffusion Mongols adapted Chinese gunpowder for war and used it against societies they attacked. Others copied this technological advantage. When the Mongols attacked Central Europe in 1240-1241, they brought gunpowder weapons with them. A century later, Europeans were using their own gunpowder weapons against each other. Origins of Gunpowder Empires Eventually Mongol expansion began to falter. Koreans resisted sporadically attempted Mongol invasions for 30 years before they surrendered. Although the Mongols were considered invincible, they failed to capture Japan. After another amphibious invasion, the Mongols successfully held Java until Kublai Khan's death. In the West, the Mamluks ended Mongol expansion toward the Mediterranean. Within a century the great urban cultures under Mongol rule revolted. But these societies had changed forever. They reorganized as land-oriented gunpowder empires with large standing armies, strong cultural identities, and a centralized administration.. Segments – th 13 Century MONGOLIA - Summary In the Century of the Stirrup, the Eurasian landmass was transformed by the emergence of a new force in history: the Mongols. Genghis Khan founded an empire that would eventually stretch from China to the Middle East, blocked only by the Mamluks in Egypt. While regular caravan travel between China and Mongolia began in 101 B.C.E., after the creation of the Mongolian Empire the trails connecting the East to the West became safe to travel. As the "Silk Road" flourished, Chinese knowledge flowed westward, stimulating new approaches to science and religion. Genghis Khan grew up among the Mongols, then rose quickly to prominence, proving himself to be an extraordinary leader. He quickly dominated the tribes of Central Asia and then went on to conquer parts of Northern China and the Islamic world. He used terror tactics to scare people into submission, sparing only skilled artisans if a town failed to surrender. Once a land was conquered, however, the Mongols were very tolerant rulers, allowing other faiths and traditions to continue. The method of Genghis Kahn's leadership was so strong that the army and empire he founded continued to grow after his death. CENTRAL ASIA - Summary The Mongols enforced law and order across Central Asia, policing a network of routes connecting East and West. They built post stations throughout the empire from which messages were carried at high speed across vast distances. The hostile impressions some foreign visitors formed changed as they spent more time with the Mongols. William of Rubruck found that in Karakorum, the main Mongol city, there were "very fine craftsmen in every art, and physicians who knew a great deal about the power of herbs and diagnosed very cleverly from the pulse.” The religious tolerance Rubruck discovered would have been unimaginable in Europe at that time. CHINA - Summary Kublai Khan continued the work his grandfather, Genghi Khan, had begun. But he also made significant land gains in China, achieving a prize that had eluded the Mongols for decades. Kublai Khan eventually rejected the harsh life of the steppes and built a luxurious palace complex in what is present-day Beijing; the poet Samuel Coleridge called it Xanadu. A visiting Venetian named Marco Polo recorded his impressions of the palace¹s grandeur: "the walls are of gold and silver. It glitters like crystal and the sparkle of it can be seen from far away." The Khan had many concubines and the women in his court held great sway over him. When Kublai's senior wife died, he lost the will to rule and retreated into a life of increasing decadence. In 1368, the conquered Chinese seized the opportunity to regain their independence. EGYPT - Summary After the rule of Kublai Khan ended, others followed China‘s lead and challenged the myth of Mongolian invincibility. The Mamluks in Cairo, Egypt, were the first soldiers to halt the Mongol military advance west. Their leader was a man called Baybars, who, like Genghis, excelled on the battlefield. He led an elite mounted corps that trained on the polo fields. At the battle of Ain Julut, in Palestine, the Mamluks dealt the Mongols their first defeat in an Islamic area and were able to protect Islam from further Mongolian domination. While not a defeat for the Mongol army as a whole, this small-scale battle had great symbolic significance. Much of the architecture in Cairo today dates back to the Mamluk era when a secure empire ensured flourishing trade. Cairo remained a leading cultura center within the Islamic world. EUROPE - Summary Europeans who had contact with Eastern knowledge often embraced new ways of thinking. A scientific revolution resulted, as Europeans began to explore and test the laws of nature. Frederick II of Sicily conducted numerous experiments, including disemboweling men to see how their digestive systems worked. Working in Paris, France, and Oxford, England, Roger Bacon dissected human eyes. His discoveries contributed to the invention of spectacles. A new religious movement encouraged people to regard the natural world as a thing to be loved and studied rather than feared. But these innovative movements would be stalled in the following century as disease and climatic change wiped out much of the population. Kublai Khan 1215 - 1294 Ruler of the Mongols from 1260, Kublai Khan completed the conquest of China that had been started by his grandfather Genghis. In 1271 he became the first emperor of the Yüan Dynasty. Establishing Beijing as his capital, Kublai boosted agriculture and business, fostered scholarship, encouraged the arts, retained many Chinese institutions, promoted religious tolerance and oversaw generally prosperous times for nearly one quarter of the world's population. The splendor of his court stirred the imagination of Western travelers, including Italian adventurer Marco Polo. Thomas Aquinas 1225 - 1274 Scholars at Europe's universities in the 13th century were arguing about the Greek texts being translated back into Latin from Arabic. Was Christian dogma correct or was the world explainable by the rationalism of Aristotelian science? Both were right, said Thomas Aquinas, a Domincan priest from Italy. Synthesizing the two traditions, he asserted that faith and reason did not conflict, that man is rational but that his highest happiness can be found in contemplation of God. Aquinas taught in Naples and Paris, advising popes and wrote the unfinished Summa theologiae, a dominant influence on Roman Catholic theology. Marco Polo 1254 - 1324 History tells of his leaving Venice at age 17 to join his father and uncle on a journey deep into Kublai Khan's China. Marco Polo himself tells in his writings how they were welcomed and spent 20 years in Asia. Polo's tales have been called products of the imagination, but whether fact or fiction, they inspired Europeans to seek out the Orient and Columbus to sail the Atlantic. Dante Alighieri 1265 - 1321 The Divine Comedy, Dante Alighieri's epic masterpiece, is an allegorical and literary triumph, a walk through the cultural, political and religious landscape of 13th century Italy. Dante's writing influenced poets from Chaucer to Byron. But his vivid depiction of the nine circles of hell terrified centuries of ordinary readers with its descriptions of horrendous punishments after death. "Dante and Shakespeare divide the modern world between them," T.S. Eliot said. "There is no third." Pope Innocent III 1160 - 1216 Lotario di Segni was only 38 when he was elected Pope Innocent III in 1198; his 18year reign dominated the Middle Ages. Claiming the right to guide the Holy Roman Empire, he launched two crusades to assert the Church's power. Meanwhile, he embraced the poor and saw the Church's rolls swell. His Fourth Lateran Council shaped the Catholic Church that we recognize today Jalal ad-Din ar-Rumi 1207 - 1273 A 13th century Sufi mystic, Jalal ad-Din ar-Rumi composed passionate love poems while turning in a circle to the beat of drums or the music of rushing water. The poems found Allah outside the Koran -- in people, nature and the commonalties of everyday life. Recorded in Persian by a disciple, they helped spread Islam to a wider audience. Rumi is still read today, and his followers, whirling dervishes (holy men), still perform their elegant, hypnotic dances to express the idea that God can be experienced in manifold ways. 13th Century Segments Mongolia Central Asia China Egypt Europe 13th Century Legacies The Mongols facilitated trade. They protected overland routes and ports linking the civilizations of Europe and Asia. Inventions as diverse as the folding fan and gunpowder traveled from Asia to Europe. Mongols brought trusted advisors and craftsman with them to newly conquered lands. A transfer of basic knowledge such as astronomy, math, and science were the results of these cross cultural exchanges between peoples of Eurasia. Large Muslim and Jewish trade communities encouraged trade between local markets and across larger regions of Asia. Genghis Khan’s army has served as a source of military strategy and an organizational model for later military commanders. The century of communication stimulated exploration in search of new trade routes once Mongol rule ended.