6AANA048 Philosophy of Language

advertisement

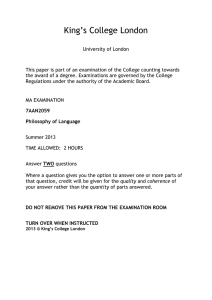

King’s College London University of London This paper is part of an examination of the College counting towards the award of a degree. Examinations are governed by the College Regulations under the authority of the Academic Board. BA EXAMINATION 6AANA048 Topics in Philosophy of Language SUMMER 2013 TIME ALLOWED: 2 HOURS Answer TWO questions Where a question gives you the option to answer one or more parts of that question, credit will be given for the quality and coherence of your answer rather than the quantity of parts answered. DO NOT REMOVE THIS PAPER FROM THE EXAMINATION ROOM TURN OVER WHEN INSTRUCTED 2013 © King’s College London 6AANA048 Answer TWO questions. 1. Bracketing ambiguity, indexicals and demonstratives, is there a significant class of English sentences such that for each of these there is the thought it expresses (in meaning what it does)? Bracketing ambiguity, and assigning references to indexicals and demonstratives where they are part of a sentence, is there a thought which is the one the sentence expresses of those references? (If you like, you can answer just one of these.) 2. What would it mean to give a negative answer to question 1, but go on to say that, nonetheless, sentences are means for expressing thoughts? 3. On what aspect of ‘say’ might it be true that a sentence says that something? What does this show? 4. What would it be to identify what a sentence means? What objection might there be to the idea that this could be done by assigning a sentence a truth-condition? What might that idea mean by a ‘condition’? 5. Consider this idea: In constructing a theory which assigned each (declarative) sentence of the language a truth-condition, one would inevitably assign each well-formed expression of the language a property an expression would have only in meaning what that one does. Explain and evaluate that idea. 6. Can an utterance of the sentence “I am here now” ever be false? SEE NEXT PAGE 6AANA048 7. Frege remarked that sometimes “the mere wording, as fixed in writing, is not the complete expression of a thought.” (“The Thought”: 64) In such a case, he suggests, the thought’s complete expression involves “accompanying circumstances” of the sentence’s use. How should this idea of accompanying circumstances be understood? How, if at all, does the meaning of the sentence in such a case fix what these are, or how they relate to the thought expressed? 8. What is the meaning of a name? What, then, does a name do? 9. Russell thought that what we ordinarily call names cannot contribute to the expression of a singular thought (anyway by functioning to make the thought expressed a singular one). Why did he think that? 10. What is a singular thought? Why are such thoughts important? (Optional: Could we do without them?) 11. Does Kaplan show us how to avoid Russell’s conclusion about what we call names? (See question 8.) If so, how does Kaplan do this? What is the general importance for semantics of what he thus shows? (If not, why not?) 12. Can two people share a psychological state and yet refer to/speak of different things when they say things like, "Water sates thirst''? 13. Frege remarks that if grammar were not a mixture of logic and psychology, there would be but one grammar. a) What role is there for psychology in grammar, but not in logic? b) Is there an identifiable part of grammar which is just logic? Discuss a or b or both, with reference to Chomsky’s idea of a human language faculty. FINAL PAGE