''Some Implications of New, High-Growth Development Trajectories: Contrasting China and India''

advertisement

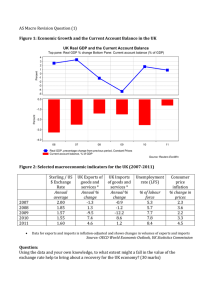

Some implications of new, highgrowth development trajectories Contrasting India and China Similarities between India and China High and sustained rates of growth of aggregate and per capita national income For longer in China than India, but growth accelerating in India recently Occurs in the context of integration through trade, investment and financial liberalization Increased presence in the global economy China and India’s contribution to global growth 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 Global 6.9 4.8 4.6 5.7 growth (% p.a.) Percentage share of annual growth rates 7.4 China 15.8 23 25.2 23.4 19.9 India 6 7.3 8.2 9 7 India and China Relative to the World (%) 1978 1985 1995 2000 Exports of goods and services (constant 2000 US$) China 1.43 1.92 2.56 3.51 India 0.54 0.52 0.88 0.80 GDP (constant 2000 US$) China 0.95 1.52 2.94 3.77 India 0.91 0.99 1.29 1.45 GDP, PPP (constant 2000 international $) China 2.92 4.58 8.75 10.99 India 3.53 3.77 4.82 5.31 Source: World Development Indicators Online 2004 2005 6.65 1.09 4.88 1.68 5.20 1.77 13.61 5.89 14.32 6.14 Importance of exports Exports of Goods and Services to GDP 40 37.46 33.95 35 30 29.56 25.13 24.57 23.3322.6 25 23.07 22.5323.3 21.75 20.95 20.3520.4 20.05 20 China India 20.54 18.42 15 15.2915.48 13.813.48 10 11 10.5910.8511.2211.66 10.0310.03 8.61 8.99 5 1991 1993 1995 1997 1999 2001 2003 2005 Difference in the Structure of Exports Chart 2: Ratio of Merchandise Trade to GDP 34.1 35 30.72 30 26.71 25 22.4 21.64 20.83 20.79 20.44 20.31 20.09 19.19 19.09 20 18.0217.99 17.64 China India 15 10 56.64 1991 8.04 7.87 7.76 8.62 8.59 8.55 8.08 7.92 1993 1995 1997 1999 11.8 10.86 9.21 9.07 9.7 9.49 2001 2003 2005 Related to differences in structure of growth Of the cumulative increase in GDP between 1991 and 2005, while 53 per cent was accounted for by industry in the case of China (with 40 per cent from services), as much as 62 per cent was accounted for by services in the Indian case (with 27 per cent from manufacturing). Manufacturing growth strong in China accounting for 37 per cent of the increment in GDP in this period, whereas the comparable figure for India was just 16 per cent. Implications of patterns of growth Fall-out of growth led by manufacturing in China in terms of demand for non-manufacturing sectors, viz. agriculture, mining and services likely to be significant, if not strong This is likely to impact on demand and growth within and outside China This would not be as true of India’s services-led growth, which is likely to impact only on the demand for manufactures and other services Trends in the sources of imports (%age distribution) 1980 China INDUSTRIAL COUNTRIES DEVELOPING COUNTRIES OTHERS India INDUSTRIAL COUNTRIES DEVELOPING COUNTRIES OTHERS 1985 1990 1995 1999 2000 2005 2006 73.7 22.8 3.5 70.4 28.1 1.5 50.1 48.3 1.6 55.4 42.7 1.9 52.3 45.1 2.6 47.0 49.8 3.2 38.1 53.5 8.5 37.4 53.2 9.4 46.5 52.8 0.7 52.7 46.6 0.6 56.9 42.5 0.6 48.5 45.5 6.0 44.7 55.3 0.0 40.5 36.1 23.4 33.3 36.4 30.3 34.8 39.3 26.0 The evidence A sharp shift away from imports from developed to developing countries starting in the mid-1980s in the case of China This is true in the case of India too, though the shift is less pronounce partly because of a lower dependence on developed countries in 1980. Imports of goods and services as per cent of GDP 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 1980 1985 1990 1995 China 2000 India 2003 World 2004 2005 Goods imports (BoP, current US$ bn) 393.6 400 350 300 250 214.7 200 150 110.1 100 50 42.4 38.2 15.1 53.9 38 23.4 68.2 0 1985 1990 1995 China 2000 India 2003 China’s Developing Country Imports (as % of world imports) DEVELOPING COUNTRIES OIL EXPORTING CTYS NON-OIL DEVELOP.CTYS WESTERN HEMISPHERE MIDDLE EAST DEV. CTYS: ASIA AFRICA DEV. CTYS: EUROPE 1980 22.8 1.4 21.4 3.7 1.8 8.7 1.5 7.2 1985 28.1 1.4 26.6 4.3 0.5 16.7 0.7 5.9 1990 48.3 2.5 45.8 2.4 0.9 38.3 0.6 6.1 1995 42.7 2.9 39.8 2.1 1.7 33.7 1.0 4.2 2000 49.8 6.0 43.7 2.4 4.5 36.7 2.4 3.8 2005 53.5 5.8 47.6 4.0 4.9 38.0 3.0 3.6 2006 53.2 6.5 46.7 4.2 5.4 36.8 3.4 3.4 In the second half of the 1980s, the sharp shift in the sources of Chinese imports was in favour of developing Asia Subsequently, the increases have been distributed to other part of the developing world India’s Developing Country Imports (as % of world imports) 1980 DEVELOPING COUNTRIES OIL EXPORTING CTYS NON-OIL DEVELOP.CTYS WESTERN HEMISPHERE MIDDLE EAST DEV. CTYS: ASIA AFRICA DEV. CTYS: EUROPE 1985 52.8 27.5 25.3 2.5 29.1 9.3 1.4 10.5 1990 46.6 18.6 28.1 2.6 20.5 9.1 2.4 12.1 1995 42.5 16.9 25.6 2.2 18.3 11.2 2.8 8.0 1999 45.5 20.6 24.9 1.5 21.4 13.9 4.6 4.2 2000 55.3 24.3 31.0 1.8 20.9 18.8 11.5 2.2 2005 36.1 10.4 25.6 1.5 9.4 17.2 6.1 1.9 2006 36.4 8.1 28.3 1.7 7.3 21.5 3.2 2.6 39.3 7.5 31.8 2.1 6.8 26.0 1.6 2.7 In India’s case the pattern is more complicated, partly because of the incompleteness of the data. Oil played an extremely important role in shaping the sources of imports. Asia’s role as a source of imports has been increasing rapidly, servicing India’s manufactured import requirements. Areas other than Asia, especially Africa, seem to be dropping out, but there is a data problem here. Cumulative post-1990 growth of imports from Africa in dollar terms 8000 7000 6000 5000 4000 3000 2000 1000 0 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 China 2000 2002 India 2004 2006 Cumulative post-1990s growth of imports from Asia in dollar terms 1800 1600 1400 1200 1000 800 600 400 200 0 -200 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 China 2000 India 2002 2004 2006 Cumulative post-1990s Growth of Imports from Latin America 3000 2500 2000 1500 1000 500 0 -500 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 China 2000 2002 India 2004 2006 Cumulative post-1990s Growth in Imports from Industrial Countries in dollar terms 1000 800 600 400 200 0 -200 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 China 2000 2002 India 2004 2006 Possible explanations Post liberalization patterns of growth may be reducing the elasticity of demand for staples with respect to GDP growth. Growth based on manufacturing in China needs more access to raw materials, whereas growth based on services in India may generate more demand for oil and final manufactures. An illustration from India Accelerating non-agricultural growth in India has been accompanied by an agrarian crisis, involving, inter alia, slow agricultural growth. In the 1990s, per capita agricultural output grew at only 0.4 per cent per year and agricultural income grew at only 0.7 per cent per year. Suggests that agriculture is no more a constraint on non-agricultural growth. Changes in the neo-liberal 1990s Change in the pattern of demand and production, involving a reduction in the direct agricultural-input dependence of the non agricultural sector. Sastry et. al. : “In 1968-69 one unit of rise in industrial output was likely to enhance demand from agriculture by 0.247 units, which was reduced to 0.087 by 1993-94. On the other hand, in 1968-69, one unit rise in industry was to cause 0.237 units demand from the services sector, which increased to 0.457 units in 1993-94.” Role of services growth Reduction in agricultural input dependence of the non-agricultural sector would be greater once we take account of the growing share of services in non-agricultural GDP. While services accounted for 43 and 48 per cent respectively of the increment of GDP at current prices in the 1970s and 1980s, the figure rose to 58 per cent and 62 per cent respectively during the 1990s and the years 2000-01 to 2004-05. Employment vs output growth Chart 6: Annual rates of employment growth for usual status workers 3.39 3.5 3.22 3 2.77 2.5 2.27 2.03 1.97 2 1.5 1.36 1 0.66 0.5 0 Rural 1983 to 1987-88 1987-88 to 1993-94 Urban 1993-94 to 1999-2000 1999-2000 to 2004-05 Source: National Sample Survey Organisation, Various Rounds Possible difference with China Dependence on modern manufacturing may be limiting the elasticity of employment with respect to output growth in China as well, with attendant implications for staples. But demand for primary raw materials including agricultural raw material and metals would be increasing. China’s consumption of Industrial Materials and Oil 1993–2002 World China's Consumption Contribution Growth (Annual % change)Per cent Metal Aluminum Copper Lead Nickel Steel Tin Zinc Oil Source: IMF (2006) 3.8 3.5 3 4.4 3.4 1.3 3.4 1.5 38 43 42 12 38 34 42 21 2002–05 World China's Consumption Contribution Growth (Annual % change)Per cent 7.6 3.8 4.3 3.6 9.2 8.1 3.8 2.2 48 51 110 87 54 86 113 30 Impact on commodity prices One major impact of the China boom has been a degree of buoyancy in commodity prices. While other factors have played a role, but for China’s presence, commodity prices may not have reflected the buoyancy they have. Over the last five years there are signs of a reversal (however temporary) of the long term trend in global commodity prices. By the beginning of this decade commodity prices had fallen relative to consumer prices (as measured by the US Consumer Price Index) for over five decades. But from around 2002, commodity prices have been on the rise. While exporters of oil have been important beneficiaries, the index of non-fuel commodity prices has also been rising. Obvious importance of non-fuel commodities Non-fuel commodities have a higher share in world trade (about 14 percent during 2000–04) than fuel commodities (7 percent). Many developing countries are highly dependent on non-fuel commodities as a source of export earnings—36 countries have a ratio of non-fuel commodity exports to GDP of over 10 percent, and in 92 countries the ratio is over 5 percent. Indeed, in many low-income countries (including in Africa), a large share of export receipts is generated by just a few commodities. Role of manufacturing based growth These trends are a result of the fact that China’s high rate of GDP growth has been (unlike in the case of India) driven by increases in industrial production. The rate of growth of industrial production in China rose from a high 10.5 per cent during 1993-2000 to 16.2 per cent during 2002-05. This industrial dynamism has meant that China today accounts for 8 per cent of global industrial value added when estimated at current exchange rates and 25 per cent when valued in PPP terms. It has also meant that China is today he largest consumer of several metals, accounting for about a quarter of the total world demand for aluminum, copper and steel Africa a major beneficiary The major beneficiary of these trends in commodity demand and prices is Africa, in which China’s presence has expanded substantially. African exports to China started accelerating around 2000, and have since risen at an annual growth rate of more than 50 per cent. By 2004, African exports to China touched $11.4 billion, reflecting a more-thanthreefold increase since 2000. By 2004 China accounted for 6 per cent of total African exports to the world. Africa’s trade with India and China Africa’s exports to India and China Implications for Terms of Trade One consequence of the rise in the volume and unit value of commodity exports from Africa, are signs of the reversal (for the present) of the long-term deterioration of net barter terms of trade faced by developing countries dependent on primary products for their export revenues that go to finance imports of manufactured products. With competition in manufactures export trade (influenced by China) moderating price increases in manufactured goods, and China’s demand driving up commodity prices, developing countries as a group and Africa in particular that are still substantially dependent on the exports of primary products, have experienced an improvement in their terms of trade. ToT and Purchasing Power of Exports (2000=100) ToT and Purchasing Power of Exports (2000=100) ToT and Purchasing Power of Exports (2000=100) ToT and Purchasing Power of Exports (2000=100) Net Impact on Africa The net result of all this is that the China boom has helped a continent like Africa. Real GDP growth in Africa rose from an average annual rate of 4.2 per cent during 2001-2004 from 3.3 per cent during 19972000. Sub-Saharan Africa gained even more with its real GDP growth rate touching 5.4 per cent in 2004, which was an eightyear high. The African Economic Outlook 2005 (AfDB/OECD 2005), among others, attributes this improvement substantially to the rise in commodity prices. Further China’s interest in the region’s natural resources has resulted in huge flows of aid and foreign investment from China to Africa, bolstering the regions infrastructure and putting much needed investment into the natural resources sector. Is this a challenge to the old Imperialism It is inasmuch as it gives other developing countries a space to negotiate the process of development But does it imply a loosening of developed country dependence for India and China That view often buttressed by the idea that India and China are exploiting the benefits of the new knowledge economy. What is the new economy? Improvement in the quality of human and other forms of ‘intangible” capital rendered possible by the knowledge revolution a crucial determinant of productivity differentials across sectors and nations. Transmission of these intangibles from the pure knowledge domain to commodities must be mediated by labour of different kinds which must acquire the necessary intangibles Requires investment geared to the production and dissemination of knowledge (i.e., in training, education, R&D, information and coordination). Role of Knowledge 1 Share in World industry value added, by selected country 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2003 All manufacturing industries Total value added ................... 100.00% 100.00% 100.00% 100.00% 100.00% 100.00% United States...................... 22.86% 23.58% 22.46% 24.23% 25.60% 23.84% European Union-15............. 36.05% 31.83% 31.41% 28.94% 26.86% 26.33% Japan................................. 15.67% 17.85% 19.34% 17.93% 16.07% 14.72% China ................................. 1.96% 2.50% 2.50% 4.48% 6.71% 9.42% India................................... 0.62% 0.74% 0.89% 1.08% 1.20% 1.35% High technology industries Total value added ............... 100.00% 100.00% 100.00% 100.00% 100.00% 100.00% United States.................. 24.56% 25.93% 24.67% 25.47% 39.58% 42.49% European Union-15 ........ 34.22% 30.27% 27.95% 26.66% 20.10% 18.45% Japan............................. 14.37% 22.41% 24.89% 23.10% 15.86% 12.07% China ............................. 0.94% 1.26% 1.25% 2.62% 5.30% 9.32% India............................... 0.14% 0.13% 0.24% 0.38% 0.35% 0.36% Role of Knowledge 2 High Technology Exports, 2004 (Current US $ billion) China 161.6 France 64.9 Germany 131.8 Hong Kong 80.1 India 2.8 Italy 23.5 Japan 124 UK 64.3 USA 216 0 50 100 150 200 250 Trends in services production Share in World service industry data, by selected country Total production ...................... 100.00% 100.00% 100.00% 100.00% United States....................... 35.54% 34.76% 34.35% 33.32% European Union-15.............. 29.92% 29.45% 29.16% 29.34% Japan................................... 14.58% 15.21% 15.81% 15.52% China .................................. 0.52% 0.75% 0.92% 1.17% India.................................... 0.52% 0.60% 0.71% 0.87% 100.00% 34.89% 28.86% 14.15% 1.51% 1.00% 100.00% 35.16% 28.54% 13.66% 1.61% 1.14% India an exporter of knowledge-intensive services IT and ITeS Exports from India: IT services exports estimated at around $23 billion in 2005-06 by RBI During the period 1990-91 to 2004-05, exports have been growing at 47.5 per cent per annum or doubling every 21 months. IT-based Growth in India In absolute and relative terms the size of the IT sector in India is now impressive. NASSCOM estimates the size of the industry in 2005-06 at $36.3 billion, of which $29.5 billion consisted of revenues from software and services. $23. 4 billion of these were export revenues: comprising of $17.1 billion of software and services export revenues and $6.3 billion of revenues from exports of IT-enabled services and business process outsourcing (BPO). The ratio of gross IT sector output to GDP rose from 0.38% in 1991-92 to 1.88% in 1999-00 and 4.5 % 2004-05 Dissociation of knowledge and production Knowledge in production separate from knowledge for production. Knowledge in services separate from knowledge for services. K4P: Domestic R&D Research and Development Expenditure, 2003 (Percent of GDP) 2.99 3 2.72 2.49 2.5 2.18 2 1.86 1.5 1.07 1 1 0.85 0.5 0 China France Germany India Italy Japan UK US Source: US National Science Board, Science and Engineering Indicators 2006 Scientific and Technical Journal Articles, 2000 196221 200000 180000 160000 140000 120000 100000 80000 55413 60000 43440 49485 30960 40000 21038 18142 10047 20000 0 China France Germany India Italy Japan UK USA Source: US National Science Board, Science and Engineering Indicators 2006 Royalty and Licence Fee Receipts, 2004 (US $ million) 50000 48137 45000 40000 35000 30000 25000 20000 15000 12271 10245 10000 5000 4066 4453 107 25 525 India Italy 0 China France Germany Japan Source: World Bank, World Developmet Indicators UK USA Retaining K4P: Absorbing talent Foreign graduate student enrollment in U.S. universities, 2004 279,076 All locations........................................................................................................... 63,013 India................................................................................................................... 50,796 China ................................................................................................................. 24,757 South Korea........................................................................................................ 15,015 Taiwan ............................................................................................................... 12,129 Canada............................................................................................................... 8,681 Japan................................................................................................................. 6,912 Turkey ................................................................................................................ 5,708 Thailand ............................................................................................................. 4,225 Mexico ............................................................................................................... 3,915 Germany ............................................................................................................ 83,925 Other locations ................................................................................................... Retaining K4P : Retaining talent Plans of foreign recipients of U.S. S&E doctorates to stay in United States Doctorate recepients 2000-03 Plans to stay Definite plans to stay All non-U.S. citizens............................................... 37,608 73.6 51.1 East/South Asia ................................................. 21,215 79.9 54.8 China ........................................................... 10,089 92.5 63.6 India.............................................................. 3,238 89.2 66.6 Retaining K4P : Global R&D Transnational corporations (TNCs) account for at least 70% of global business R&D. In 2002, the top 700 R&D spenders reported R&D expenditures of more than $300 billion (WIR 2005). Ford, Pfizer, DaimlerChrysler, Siemens, Toyota and General Motors each spent more than $5 billion on R&D in 2003. In comparison, among the developing economies, total R&D spending exceeded $5 billion only in Brazil, China, the Republic of Korea and Taiwan Province of China. Retaining K4P : Internationalizing R&D A rising share of these companies' R&D expenditures are undertaken in developing countries. Between 1994 and 2002, the developing-country share of all overseas R&D by US TNCs increased from 7.5% to 13%. Today, more than half of the world's top R&D spenders conduct R&D activities in China, India or Singapore. Role for foreign firms in India and China China’s trade surplus with the US rose to $114.2 billion in 2005, up from $80.2 billion in 2004. Exports to the US rose by over 30 per cent to $162.9 billion and imports totaled $48.7 billion. But dominant share of exports from foreign invested firms. More than 60 per cent of India’s IT services exports are to the US. But more than 50 per cent of ITeS exports from captive units. Increase in US Presence in Asia In Asia and Pacific, value added of foreign affiliates in 1999–2004 grew at an average annual rate of 9 percent, and the region’s share increased 1.2 percentage points, to 19.0 percent. The largest increases in shares were in China, India, and Japan. The China Boom In China, value added of affiliates in manufacturing accounted for more than two-thirds of the value added of all Chinese affiliates in 2004, and during 1999–2004, value added of Chinese affiliates in manufacturing grew at an average annual rate of 23 percent. In 2004, more than two-thirds of the sales by Chinese affiliates in manufacturing were to customers in China, and only 7.4 percent of these sales were to U.S. customers, down from 16.3 percent in 1999. India and Japan In India, the growth in value added was widespread by industry, but it was most notable in manufacturing and wholesale trade, in which affiliates sell almost exclusively to local customers, and in computer systems design and related services (part of professional, scientific, and technical services), in which affiliates sell mainly to customers in the United States. In Japan, most of the growth in value added was in manufacturing, mainly reflecting acquisition of firms or establishment of new foreign affiliates to serve the local market. Impact on trade 1 Table 4.4: US intra-firm imports in ICT goods and services, 2004 USD millions and percentage shares Total Related Share imports party % trade All goods 1460160 697561 47.8 Computer equipment 73733 51731 70.2 Communication equipment 38733 28106 72.5 Audio & video equipment 37054 24282 65.5 Electronic components 65351 43690 66.9 Magnetic & optical media 4096 2160 52.7 ICT products 218967 149969 68.5 ICT share of total 15 21.5 .. All services 258069 54693 21.2 Computer & information services 5804 3800 65.5 ICT share of total 2.2 6.9 .. Source: OECD, Information Technology Outlook 2006 The distributed value chain China’s exports of EDP and office equipment China’s imports of integrated circuits and electronic components 2000 2004 5.02 20.73 6.80 22.40 Semiconductor market shares Europe 13% ROW 1% United States 49% Japan 37% Exporting knowledge The United States continues to be a net exporter of manufacturing technological know-how sold as intellectual property: On average, royalties and fees received from foreign firms were three times greater than those paid out to foreigners by U.S. firms for access to their technology. In 2003, U.S. receipts from the licensing of technological know-how to foreigners totaled $4.9 billion, 24.4% higher than in 1999. The most recent data show a trade surplus of $2.6 billion in 2003, 28% higher than the prior year but lower than the $3.0 billion surplus recorded in 2000. Implications Emergence of a new global division of labour. Interpreting the Chinese and Indian miracles: Instruments of battle rather than warriors. Miracles always exist, but they are never the same. There are, however, some signs of change in China. K4P: Are things changing? Gross Domestic Expenditure on R&D (billion current PPP $), 1981-2006 19 8 19 1 8 19 2 8 19 3 8 19 4 8 19 5 8 19 6 8 19 7 8 19 8 8 19 9 9 19 0 9 19 1 9 19 2 9 19 3 9 19 4 9 19 5 9 19 6 9 19 7 9 19 8 9 20 9 0 20 0 0 20 1 0 20 2 0 20 3 0 20 4 0 20 5 06 350 300 250 200 150 100 50 0 Source: OECD, Main Science and Technology Indicators, 2006. Japan United States EU-15 China Germany R&D in China Since 1995, China has not only more than doubled its R&D spending as a percentage of GDP from 0.6 to 1.3% of GDP, but the number of researchers was also increased by 77% between 1995 and 2004 China will spend some €102 billion on R&D in 2006, a little more than Japan's forecast of €97 billion. The United States is expected to remain the world's top R&D investor in 2006 with some €248 billion, whereas the EU-15, is expected to invest around €173 billion. The EU-25 R&D expenditure in 2004 amounted to 1.9% of GDP, some €195 billion.