Indulgence, Restraint, and Within-Country Diversity: Exploring Entrepreneurial Outcomes with New Constructs

advertisement

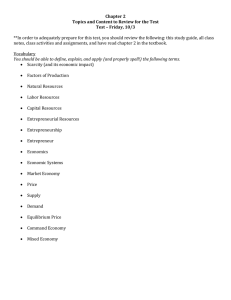

13th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 INDULGENCE, RESTRAINT, AND WITHIN-COUNTRY DIVERSITY: EXPLORING ENTREPRENEURIAL OUTCOMES WITH NEW CONSTRUCTS Authors: Heidi A. Hicks Saginaw Valley State University Lisa A. Maroni Embry Riddle University Rosalie A. Stackpole Michigan Economic Development Corporation Zachary P. Gibson Saginaw Valley State University George M. Puia Saginaw Valley State University Contact: George Puia, PhD Dow Chemical Company Centennial Chair in Global Business Saginaw Valley State University 7400 Bay Road University Center Michigan 48623, USA +1.989.964.6074 puia@svsu.edu Professional Biographies Heidi Hicks is a business management student at Saginaw Valley State University. She was competitively selected to be a Fellow of the Vitito Global Leadership Institute. Her research interests are in the effects of culture on entrepreneurship. November 22-23, 2015 Oxford, UK 1 13th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 Lisa A. Maroni received a BA in International Studies-Business from Saginaw Valley State University and a MEd in Counseling-Student Affairs from Northern Arizona University. While a student, she served as a William Jefferson Clinton Scholar at the American University in Dubai, was a Saginaw Valley State University Roberts Fellow and studied as an exchange student at Shih Hsin University in Taipei. She is currently the Assistant Director of International Recruitment and Admissions at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University in Prescott, Arizona. Rosalie A. Stackpole received degrees in Marketing and Management from Saginaw Valley State University. While at SVSU, she was competitively selected to be a Fellow of the Vitito Global Leadership Institute within the College of Business, where she completed and presented Super Bowl advertising research. Rosalie has a wide array of work experiences that range from the financial industry to international trade. Zachary P. Gibson studies marketing at Saginaw Valley State University where he was competitively selected to be a Fellow of the Vitito Global Leadership Institute. He has presented research on writing center techniques and family business. George M. Puia, Ph.D. holds the Dow Chemical Company Centennial Chair in Global Business at Saginaw Valley State University. He earned a Ph.D. in Strategic Management with concentrations in international business and research methods from the University of Kansas. Dr. Puia has authored books, book chapters, case studies and refereed articles on international business. He was named an AGBA Distinguished Fellow by the Academy for Global Business Advancement. Professor Puia also holds the CGRP certification (Certified Global Business Practitioner). He has served as journal editor, on editorial boards, and has held numerous academic leadership positions. November 22-23, 2015 Oxford, UK 2 13th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 INDULGENCE, RESTRAINT, AND WITHIN-COUNTRY DIVERSITY: EXPLORING ENTREPRENEURIAL OUTCOMES WITH NEW CONSTRUCTS ABSTRACT Purpose The purpose of this paper is to explore the relationships between culture, cultural diversity, and two specific entrepreneurial outcomes: Total Entrepreneurial Activity and Fear of Failure. To provide comparability with prior literature, the paper includes economic context covariates common to other entrepreneurship studies. Design/Methodology The paper uses a multivariate analysis of variance approach to analyzing publicly available data on culture, economic covariates, and entrepreneurship. Findings Both economic and cultural variables were significantly associated with entrepreneurial outcomes. In particular, the paper found support for the effects of indulgence and within-country diversity. Research Implications Research studies tend to look at economic and cultural effects independently and with only a few exceptions, to ignore within country diversity entirely. This paper extends the literature by jointly testing economic, cultural, and diversity variables. Additionally, this is one of the first papers to utilize the more recent Hofstede construct of indulgence-restraint in analyzing entrepreneurial outcomes. Social Implications Policy makers can change economic models but are largely unable to adjust national culture. Within-country diversity however is frequently changed through revised work rules and visa policies. The paper potentially opens new policy frameworks for decision makers. Originality This is the first paper to utilize the more recent Hofstede construct of indulgence-restraint in analyzing entrepreneurial outcomes. Additionally, the paper adds the construct of within country diversity to the entrepreneurship research dialogue. Keywords: Entrepreneurship, culture, cultural diversity, indulgence, failure, regulation, economic freedom November 22-23, 2015 Oxford, UK 3 13th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 INDULGENCE, RESTRAINT, AND WITHIN-COUNTRY DIVERSITY: EXPLORING ENTREPRENEURIAL OUTCOMES WITH NEW CONSTRUCTS INTRODUCTION There is substantial research on factors that differentiate a nation’s capacity for innovation and entrepreneurship (Kogut, 1991; Porter, 2000; Nelson, 1993; Porter and Stern, 2004). Scholars have explored a wide range of constructs that potentially influence the national environmental context, including: political frameworks (Lenway & Murtha, 1994; Spencer, Murtha & Lenway, 2005), economic frameworks, and level and quality of regulation (Puia and Minnis, 2007). There has also been significant research linking culture and cultural diversity to national levels of innovation and entrepreneurship (Shane, 1992; Ambos & Schlegelmilch, 2008; Herbig & McCarty, 1993; Steensma, Marino, Weaver & Dickson, 2000; Rhyne, Teagarden & W. Van den Panhuyzen, 2002; Puia and Ofori-Dankwa, 2013). Culture and entrepreneurship studies have relied heavily on the work of Hofstede, particularly his original four constructs of individualism, power distance, uncertainty avoidance, and masculinity (Hofstede, 1980). Recently, the Hofstede framework has been extended to include a construct for indulgence-restraint (Hofstede, et al, 2008). This paper will test whether Hofstede’s measure of indulgence has explanatory power in regards to certain entrepreneurial outcomes. Additionally, the paper will explore the influence of within-country diversity on entrepreneurial outcomes. A more sound understanding of how indulgent cultures function as pertaining to entrepreneurship would offer researchers new avenues for exploring antecedents of firm creation. Further, researching aspects of culture on entrepreneurship has the potential to open dialogue between academics and policy makers. Finally, practitioners might identify supportive national contexts for ventures and investments. THEORETICAL BACKGROUND Entrepreneurial outcomes In order to better understand the forces that influence entrepreneurship, scholars have measured a wide range of entrepreneurial outcomes: impact of entrepreneurs on the economy,job creation,wealth creation, and new business startups among others. One group of scholars, the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) Consortium, worked to create a common set of metrics that could afford scholars the opportunity to research and compare entrepreneurs across nations. For this paper, we chose two metrics from the GEMstudies: Total Entrepreneurial Activity and Fear of Failure.The Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) is a research project that began in 1999, and has provided substantial data on various countries’ attitudes towards entrepreneurship, November 22-23, 2015 Oxford, UK 4 13th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 start-up businesses, and goals of entrepreneurs (Bosma, 2013). On an annual basis, GEM surveys over 150,000 people in over 50 countries (Lepoutre, et al., 2013). Total Entrepreneurship Activity (TEA) is used to measure entrepreneurship at a national level. TEA is defined as the percentage of individuals aged 18-64, who are either nascent entrepreneurs or owner-managers of a new business (Slinger, et al., 2015). By adding nascent entrepreneurs, those actively involved in setting up a business that they will own outright or coown but who are not currently receiving any ownership payments, to those who have an established new business that is less than 42 months old, the GEM data is able to capture a full range of early entrepreneurial activity. TEA is widely used in the entrepreneurship data (Levie, et al., 2014). Baksi (2014) used TEA to determine if entrepreneurship and innovation were positively correlated to economic growth. Fear of failure rate As researchers, we were interested not only in factors that enable entrepreneurship, but also those that inhibit its development. To that end, we chose to study fear of failure (FFR) as a factor that potentially slows entrepreneurial growth. As noted in a recent literature review (Cacciotti and Hayton, 2015), the relationship between fear and entrepreneurship should be a focus for new research. Martins (2004) believes that fear of failure (FFR) is both a cultural and social barrier to entrepreneurship.According to GEM, 32.53% of individuals aged 18-64 involved in any stage of entrepreneurial activity report that fear of failure would prevent them from setting up a business, (Singer, et. al, 2015). Fear of failure plays a significant role in the absence of business start-ups. In 2005, Bosma, et al., studied the 16 European Union countries and found that on average 37% of adults indicated that fear of failure would prevent them from setting up a business, while only 29% of adults in four Anglo countries felt the same way. Across all 34 GEM countries in their study, researchersfound consistent patterns of cultural and demographic influences (Bosma, Hunt, et. al, 2005). Independent variables/covariates There are several constructs that have been shown to influence entrepreneurship and innovation in the prior research. These constructs can be divided into two categories: economic and cultural. This section documents the literature in support of the inclusion of these variables. Regulatory quality Countries differ substantially in the ways they regulate entrepreneurs (Djankov et al. 2002). Business regulation can be valuable to both the entrepreneur and the country. For example, business registration or licensing can add legitimacy to a new venture. At the opposite extreme, some regulation can be developed for the benefit of political and business elites (McChesney 1987, Djankov et al. 2002). To this end, Shleifer and Vishny (1993) infer that public officials create regulations as means of incenting forms of official facilitating payments (grease payments). Significantly, the World Bank (2004) report noted that firms with lower regulation levels have a better functioning entrepreneurial economy. In their work, Kauffmann and Kray (2002) posit that one can measure whether regulations are helpful or are harmful to this business environment. This study uses Kauffmann’s measure of regulatory quality to indicate November 22-23, 2015 Oxford, UK 5 13th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 whether governments manage regulations in ways that are supportive of business. These measures are constructed on a wide set of parameters, including voice and accountability, political stability, absence of violence, government effectiveness, regulatory quality, rule of law, and control of corruption (Kaufmann, et. al, 2008). Once measured, these are combined to give a country’s regulatory quality index. Based on the above, we offer the following hypotheses. H.1.a. Countries with better scores on the Kauffman Regulatory Quality Index will have higher levels of TEA H.1.b. Countries with weaker scores on the Kauffman Regulatory Quality Index will have higher levels of FFR Economic Freedom Index There is a significant body of literature that relates economic freedom to innovation and entrepreneurship. “Economic freedom” measures the extent of an in-place market economy, one that includes free competition, exchange without coercion, and protection of property (Gwartney and Lawson 2002).In a 2003 study,Berggren found a significant positive relationship between economic freedom and economic growth. Similarly, Gwatney et al., (1999) wereable to connect economic freedom with favorable conditions for entrepreneurs. O’Drisoll, Jr. et al (2002) developed an “index of economic freedom (IEF)” to provide a more rigorous approach to its measurement. The ten indices of the IEF measure are: business freedom, trade freedom, fiscal freedom, government size, monetary freedom, investment freedom, financial freedom, property rights, freedom from corruption, and labor freedom. Using this measure, Gardner et al (2014) found economic freedom to be a pivotal factor for entrepreneurship to prosper. H.2.a: Economic freedom will be positively associated with (TEA) H.2.b. Economic freedom will be negatively associated with fear of failure (FFA) Indulgence Indulgence as a measure of culture is a fairly recent addition to the literature (Hofstede, 2008). The concept of indulgence describes a society that “allows relatively free gratification of basic and natural human desires related to enjoying life and having fun” (Hofstede, 2011). Characteristics of a highly indulgent society include a perception of personal control over one’s life, high value being placed on freedom of speech, and less concern for maintaining order in a nation.Collier et al. (2013), noted that people in indulgent societies prefer happiness and tend to create a perception of freedom, health, and control over life (Collier et al., 2013). In Hofstede’s metric (2011), “restraint” is the opposite of indulgence, controlling gratification of needs through social norms. Characteristics of a highly restrained society include a perception of helplessness, lower concern for freedom of speech and a higher amount of police per capita. As of this writing, there are no indexed articles relating indulgence to entrepreneurship. Once and Almagtome (2015) found a relationship between indulgence and environmental reporting; the more indulgent a culture, the more likely it was to have higher levels of corporate environmental disclosure. Correlation results have also shown that indulgence was positively related to the UN Human Development Index (Gaygisiz, 2013), suggesting a relationship November 22-23, 2015 Oxford, UK 6 13th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 between income, development, and indulgence. Considering the nature of restraint, we would anticipate nations with a restrained culture would exhibita greater fear of failure. H.3.a. Indulgence will be significantly and positively associated with TEA H.3.b. Indulgence will be significantly and negatively associated with FFR (the more restrained you are, the more likely you will be to fear failure) Individualism According to Hofstede (2001), individualism represents a “loosely framed society” where group interests are secondary to that of the individual. As a result, individuals are allowed to pursue personal goals and interests (Hofstede, 2001). Individualistic cultures appreciate creative and progressive behavior, attributes associated with entrepreneurship (Chang 2003). Shane’s seminar work (1992) found a significant positive relationship between individualism and business-led economic growth. Puia and Ofori-Dankwa (2013) found significant positive effects of individualism inthe generation of both patents and trademarks. Currently, the literature has not explored the relationship between individualism and fear of failure. The literature clearly suggests that in individualistic cultures, success is earned rather than attributed. As a result, in individualistic cultures there is greater pressure on the individual to perform (Hofstede, 2001). H.4.a: Individualism will be significantly and positively associated with TEA H.4.b. Individualism will be significantly and positively associated with FFR Cultural Diversity Prior literature treated national cultures as uniform and monolithic while in reality national cultures have sub-cultures with attributes that are distinct from the dominant cultures (Early & Gibson, 1998, Schwartz, 1990). The Hofstede (2001) indices measure national cultural characteristics as central tendencies, comparing countries on their mean score for a given cultural characteristic without reporting deviations. Au (1999) suggested that scholars’ can addresses the limitation of central tendencies by focusing on within-country diversity, or intra-cultural variation (ICV). Au (1999, 2000)identified several ICV dimensions like spoken languages and ethnic composition as being associated with national outcomes such as technological innovation and productivity advances. In their work, Puia and Ofori-Danwka (2013) using the number of active languages as a measure of ethno-linguistic diversity, found a strong positive correlation between diversity and measures of innovation. H.5.a. Ethno-linguistic diversity will be significantly and positively associated with TEA. H.5.b. Ethno-linguistic diversity will be significantly and positively associated with FFR Income Classification The income classification of a country potentially influences its entrepreneurial profile. There is a known relationship between national income and high-technology innovation (Shane, 1992), a form of entrepreneurship that favors high-income countries. At the opposite end of the November 22-23, 2015 Oxford, UK 7 13th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 spectrum, low-income economies have fewer employment opportunities and thus generate more necessity entrepreneurs. To hold constant for the effects of income, we have chose touse the World Bank Income Classifications (WBIC). The World Bank classifies countries as follows:low-income economies are defined as $1,045 or less, lower-middle-income of $1,046 to $4,125, upper-middle-income of $4,126 to $12,736 and high-income of $12,737 or more (World Bank, 2015). Tang and Koveos (2004) used the income classification to separate high and low income countries to refine the correlation between national GDP and entrepreneurship. Additionally, Portugal-Perez and Wilson (2009) use the WBIC to categorize economic prosperity of African nationals when analyzingtrade facilitation. RESEARCH DESIGN The following paragraphs describe the research design including sample characteristics, measures, and statistical methods. Sample Characteristics Our initial population was the 186 countries included in the Economic Freedom Index. There were 107 countries included in the GEMS database. The Hofstede dataset on culture included only 77 nations. The number of active languages was drawn from the Ethnologue database. Given the limited set of cultural data, the authors were constrained to those countries for which measures of culture existed with the other covariates. While this is a limitation, the Hofstede countries do cover all continents, most developed countries, and a wide range of cultures. Measures The dependent measures of TEA and FFR were drawn from the GEM data set. Culture was measured as indicated earlier through the use of two Hofstede variables, individualismcollectivism (where higher scores represented more individualistic cultures) and indulgencerestraint. To capture diversity, we input data on the number of active languages from the UN/SIL Ethnologue Database (Studer, 1998). The Index of Economic Freedom is on a continuous scale of one to five, where one equals complete economic freedom and a score of five represents a totally repressed economy. Regulatory quality was represented by the Kauffman Regulatory Quality index. Differences in income were represented using the World Bank indicators (WBIC). Statistical Methods Few papers have jointly tested the effects of pubic policy frameworks and culture on business outcomes (Murtha and Lenway, 2004); a review of the literature found only a limited set of articles that jointly explored policy orientations and culture and their effects on entrepreneurship (Puia and Minnis, 2007).The authors chose a two-stage data analysis process. First, given the relatively small sample size, the correlation between two dependent variables (r=-0.45), and the desire to reduce Type-1error, the analysis began with a MANOVA (Hair, et al, 1998). Additionally, the two dependent variables share a theoretical association with start-sups, suggesting they be treated as a group for analytical purposes (Stevens, 1992). Following the MANOVA, the two dependent variables were regressed independently. November 22-23, 2015 Oxford, UK 8 13th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 RESULTS Descriptive statistics and correlations are presented in Table 1. Table 2 provides the overall regression results and the coefficients from the independent regression analyses. The multivariate F-tests for the model were highly significant. Using Wilk’s Lambda, the F-value for the overall model was 9.81 with p=0.000. For the corrected model of tests between subjects, TEA achieved an F value of 7.441 with p=0.000. For the FFA model, the F value was 3.323 with p=0.006. Given the significance of the multivariate model, we conducted regression analysis of the two dependent variables. For TEA, the model had an Adjusted R-Squared of 0.466. For FFR, the model had an adjusted R-Squared of 0. 273. For each model, we tested three economic variables and three cultural ones. In regards to Total Entrepreneurial Activity (TEA), regulatory quality (H1.a) was in the correct direction but not significant (p=0.059); economic freedom (H2.a) was significant (p=0.032). The World Bank Income classification was insignificant (p=0.514). As to the cultural variables, TEA was significantly associated with all three metrics. Indulgence (H3.a) was highly significant (p=0.000), a strong finding for the first test of this metric. Individualism (H4.a) was also highly significant with p=0.007. Our third cultural measure looked at within country diversity; the number of active languages (H5.a) was also significant (P=0.044). We also regressed fear of failure against three economic variables and three cultural ones. In regards to FFR, regulatory quality (H1.b) was significant (p=0.014); economic freedom (H2.b) was not significant (p=0.156). The World Bank Income classification was not significant (p=0.720). As to the cultural variables, FFRwas significantly associated with two of the three cultural metrics. Indulgence (H3.b) was again highly significant (p=0.000). Individualism (H4.b) was in the right direction, but was short of significance (p=0.082). Cultural diversity as measured by the number of active languages (H5.b) was highly significant (P=0.000). DISCUSSION The purpose of this paper was to explore the relationship between culture and cultural diversity variables on two specific entrepreneurial outcomes, “Total Entrepreneurial Activity” and “Fear of Failure” while holding constant for anticipated economic effects. Clearly, there were significant effects on entrepreneurial outcomes from both culture and economic policy. While the overall model and the individual regression equations were both significant, there were some interesting outcomes that motivate further research. Economic freedom was significantly related to total entrepreneurial activity but not to fear of failure, suggesting that fear of failure may have a unique set of economic antecedents.Additionally, the coefficient of determination for the FFR equations was lower than for TEA. In part, fear of failure might relate as much to personality characteristics as cultural ones (Carraher, et al., 2010). Additional research is warranted. As one of the first papers to explore the role of indulgence in entrepreneurship, we were not surprised that the results suggested a complex layering of effects. In terms of TEA, there is a positive and significant relationship between indulgence and entrepreneurship,the more indulgent a society the greater the entrepreneurial activity.This is in unique contrast to the relationship of November 22-23, 2015 Oxford, UK 9 13th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 indulgence to fear of failure with is inversely correlated, the more restrained a culture, the greater the fear of failure. Hofstede (2011, p.16) noted “restrained people have a perception of helplessness”. The potential relationship between fear of failure and a sense of helplessness opens clear avenues for future research. Research studies tend to look at economic and cultural effects independently and with only a few exceptions, to ignore within country diversity entirely. This paper extends the literature by jointly testing economic, cultural, and diversity variables. Additionally, this is one of the first papersto utilize the more recent Hofstede construct of indulgence-restraint in analyzing entrepreneurial outcomes. The results suggest additional new research opportunities, e.g., exploring the role of indulgence-restraint in entrepreneurial finance, examining the role of cultural diversity and new cultural variables in exploring necessity entrepreneurship, etc. There were limitations to this research project. While the Hofstede and linguistic data had significant associations with economic activity, they offer a less than complete view of culture. In 2012, Adham found unique attributes of technological innovation and entrepreneurship from the Islamic perspective. Contemporary interpretations of Islamic law put restrictions on business practices. Adham’s 2012 paper suggests new research opportunities in exploring differences between cultures based on religious diversity in addition to linguistic diversity. An additional limitation of the Hofstede data is that it under-represents low-income and developing nations. Given the importance of entrepreneurship to economic development, we need to find better metrics for capturing culture in emerging economies. As an additional limitation, this paper used cross-sectional analysis. This is appropriate for measures of culture which are theoretically robust in respect to time. In terms of economic metrics, there are limitations to cross sectional analysis in an environment where nations frequently adjust their policies. Theory development would benefit from the exploration of economic policy in a time-series context. Policy makers can change economic models but are largely unable to adjust national culture. Within-country diversity however is frequently changed through revised work rules, visa policies, and large-scale immigration. The paper potentially opens new policy frameworks for decision makers. In a global business context, entrepreneurs have the opportunity to select the location of their new ventures independent of their initial national context (Knight and Cavusgil, 2004). This research helps entrepreneurs evaluate factors that may contribute to the success of a new venture. Additionally, entrepreneurial firms can gain from adding cultural diversity; they are not limited by the diversity of their national surroundings. REFERENCES Adham, K.A., Said, M.F., Muhamad, N. S., and Yaakub, N.I. (2012), “Technological Innovation and Entrepreneurship from the Western and Islamic Perspectives”, International Journal of Economics, Management, and Accounting, Vol. 20, No. 2, pp. 109-148. November 22-23, 2015 Oxford, UK 10 13th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 Ambos, B., & Schlegelmilch, B. (2008), “Innovation in Multinational Firms: Does Cultural Fit Enhance Performance?” Management International Review, Vol. 48, No.2, pp. 189-206. Au, K.Y. (2000),“Intra-cultural Variation as Another Construct of International Management: A Study Based on Secondary Data of 42 Countries”, Journal of International Management, Vol. 6, pp. 217-238. Au, K.Y. (1999),“Intra-cultural variation: Evidence and implications for international business”, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 30, No. 4, pp. 799-812. Baksi, A. K (2014), “Exploring the Relationship Between Entrepreneurship, Innovation and Economic Progress: A Case of India with Evidences from GEM Data and World Bank Enterprise Surveys”, Journal of Entrepreneurship and Management, Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 2332. Berggren, N. (2003), “The benefits of economic freedom: A survey”, The Independent Review, pp. 193-211. Bosma, N (2013), “The Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) and Its Impact on Entrepreneurship Research”, Foundations and Trends in Entrepreneurship, Vol. 9, No. 2. Bosma, N., Hunt, S., Wennekers, S., and Hessels, J. (2005), “Early-stage entrepreneurial activity in the European Union: some issues and challenges”, working paper, Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis, St. Louis, March 2005. Cacciotti, G. and Hayton, J. C. (2015), “Fear and Entrepreneurship: A Review and Research Agenda”, International Journal of Management Reviews, Vol. 17, pp. 165–190. Carraher, S. M., Buchanan, J. K., & Puia, G. (2010),“Entrepreneurial need for achievement in China, Latvia, and the USA”, Baltic Journal of Management, Vol. 5, No. 3, pp. 378-396. Chang, L.C. (2003), “An examination of cross-cultural negotiation: Using Hofstede framework”, Journal of American Academy of Business, Vol. 2, No. 2, pp. 567-570. Collier, A., Deng, H., Zhao, F. (2013), “A multidimensional and integrative approach to study global digital divide and e-government development”, Information Technology & People, Vol. 27, No. 1, pp. 38-62. Djankov, S., La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., and Shleifer, A. (2002),“The Regulation of Entry”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 117, pp. 1-37. Early, P.C., and Gibson, C. (1998), “Taking stock of our progress on individualism / collectivism: 100 years of solidarity and community”, Journal of Management, Vol. 24, No. 3, pp. 265-304. Gaygisiz, E. (2013), “How are cultural dimensions and governance quality related to socioeconomic development?” Journal of Socio - Economics, Vol. 47, pp. 170. Gardner, J.C., McGowan, C.B., Sissko, M. (2014), “Entrepreneurship and Economic Freedom”, International Journal of Entrepreneurship, Vol. 18, pp. 101-112. Gwartney, J., & Lawson, R. (2002), Economic freedom of the World: 2002, Vancouver: The Fraser Institute. Gwartney, J., Lawson, R. & Holcombe, R.G. (1999), “Economic freedom and environment for economic growth”, Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics, Vol. 112, No. 3, pp. 335-344. Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., and Black, W. C. (1998), Multivariate Analysis, 5th ed. Prentice Hall, New Jersey. Herbig, P.A. and McCarty C. (1993), “National management of innovation: Interactions of culture and structure”, Multinational Business Review, Vol. Spring, pp. 19 – 26. Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., Minkov, M., & Vinken, H. (2008), Values survey module 2008. November 22-23, 2015 Oxford, UK 11 13th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 Hofstede, G., Minkov, M. (2011), “The evolution of Hofstede’s doctrine”, Cross Cultural Management: An International Journal, Vol. 18, No. 1, pp. 10-20. Hofstede, G. (2011), “Dimensionalizing Cultures: The Hofstede Model in Context” Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, Vol. 2, No. 1. Hofstede, G. (2001), Culture's Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations Across Nations, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage. Hofstede, G. (1991), Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind. London: McGraw-Hill Book Company. Kaufmann, D., and Kraay, A., (2002), Governance Indicators, Aid Allocation, and the Millennium Challenge Account, World Bank.Kogut, B. (1991), “Country capabilities and the permeability of borders”, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 12(Summer/Special Issue) pp. 33-47. Kaufmann, D. Kraay, A. and Mastruzzi, M. (2008),“Governance matters VII: Aggregate and individual governance indicators 1996-2007”. Washington DC: World Bank. Knight, G. A., & Cavusgil, S. T. (2004),“Innovation, organizational capabilities, and the bornglobal firm”, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 35, No. 2, pp. 124-141. Lenway, S.A., and Murtha, T.P. (1994), “The state as strategist in international business research”, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 25, No. 3, pp. 513-536. Lepoutre, J., Justo, R., Terjense, S., Bosma, N. (2013), “Designing a global standardized methodology for measuring social entrepreneurship activity: the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor social entrepreneurship study”, Small Business Economics, Vol. 40, No. 3, pp. 693-714. Levie, J., Autio, E., Acs, Z., & Hart, M. (2014), “Global entrepreneurship and institutions: an introduction”. Small Business Economics, Vol. 42, No,3, pp. 437-444. Martins, S. (2004), “Barriers to entrepreneurship and business creation”, ADRIMAG, pp.2. Murtha, T. P. and Lenway, S. A. (1994), “Country capabilities and the strategic state: How national political institutions affect multinational corporations’ strategies”, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 15 (Special issue) pp.113-130. Nelson, R.R. (1993),National Innovation Systems: A comparative analysis, New York: Oxford University Press. Once, S. and Almagtome, A. (2015), “The impact of national cultural values on environmental reporting”, Economic and Social Development proceedings, Varazdin Development and Entrepreneurship Agency, Croatia. Porter, M.E. (2000),“Attitudes, values, beliefs and the micro-economics of prosperity”, Harrison, L.E. and Huntington, S.P., Culture Matters: How values shape human progress. New York: Basic Books. Porter, M.E., and Stern, S. (2004), Ranking National Innovative Capacity: Findings from the National Innovative Capacity Index, in World Economic Forum, M.E. Porter, K. Schwab, X. Sali-Martin, and A. Lopez Carlos (eds.) The global competitiveness report, New York: Oxford University Press. Portugal-Perez, A. & Wilson, J. S. (2009), “Why Trade Facilitation Matters to Africa”, World Trade Review, Vol.8, pp.379-416. Puia, G.M., and Minnis, W. (2007), “The Effects of Policy Frameworks and Culture on the Regulation of Entrepreneurial Entry”, Journal of Applied Management and Entrepreneurship, Vol. 12 No. 4, pp. 36-50. November 22-23, 2015 Oxford, UK 12 13th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 Puia, G.M. and Ofori-Dankwa, J. (2013), "The effects of national culture and ethnolinguistic diversity on innovativeness", Baltic Journal of Management, Vol. 8, No.3, pp. 349 – 371. Rhyne, L.C., Teagarden. M.B. and Van den Panhuyzen, W. (2002), “Technology-based competitive strategies: The relationship of cultural dimensions to new product innovation”, The Journal of High Technology Management Research, Vol.13, pp. 249 – 277. Schwartz, S.H. (1994), “Beyond individualism/ collectivism: New cultural dimensions of values”. In U. Kim, H.C. Triandis, G. Kagitcibasi, S.C. Choi, and G. Yoon (eds.), Individualism and collectivism: Theory, method, and applications. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. Shane, S.A. (1992), “Why do some societies invent more than others?” Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 7, pp. 29–46. Shleifer, A. and Vishny, R. W. (1993), “Corruption”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 153, pp. 599-617. Slinger, S. Amorós, J.E., and Moska, D. (2015), Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, 2014: Global Report, Global Entrepreneurship Research Association. Spencer, J.W., Murtha, T.P., and Lenway, S.A., (2005), “How Governments Matter to New Industry Creation”, Academy of Management Review. Vol. 30, No. 2. pp. 321-337. Steensma, H.K., L. Marino, Weaver, K.M., and Dickson, P.H. (2000), “The influence of national culture on the formation of technology alliances by entrepreneurial firms”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 43 No. 5, pp. 951 – 973. Stevens, J, (1992), Applied Multivariate Statistics for the Social Sciences, 2nd ed., Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Studer, Gerald. (1998), Review of Ethnologue language family index to the thirteenth edition of the Ethnologue, Grimes, Joseph E. and Barbara F. Grimes, compilers. SIL Press, Geneva. Tang, L., and Koveos, P. E. (2004), “Venture Entrepreneurship, innovation Entrepreneurship, and Economic Growth”, Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, Vol. 9,pp. 160-171. November 22-23, 2015 Oxford, UK 13 13th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 Table 1: Descriptive Statistics and Correlations Correlation (Pearson) Variable Name TEA-Total Early Stage Entrepreneurial Activity Mean Std. Dev. TEA FFR EFI RQI IC IR NAL 12.36 6.99 1 -0.458 -0.258 -0.429 -0.550 -0.340 -0.306 0.000 0.049 0.001 0.000 0.013 0.019 1.000 0.124 0.247 0.276 -0.444 -0.048 0.349 0.059 0.034 0.001 0.720 1.000 0.848 0.493 0.209 -0.238 0.000 0.000 0.125 0.063 1.000 0.625 0.272 -0.221 0.000 0.045 0.84 1.000 0.096 -0.145 0.485 0.259 1.000 0.073 Sig. (2-Tailed) FFR-Fear of Failure 35.41 8.83 Sig. (2-Tailed) EFI-Economic Freedom Index 0.000 65.26 10.53 Sig. (2-Tailed) RQI-Regulatory Quality Index (Kauffman) 2.54 9.25 Sig. (2-Tailed) IC-Individualism Collectivism (Hofstede) 43 23.6 Sig. (2-Tailed) IR-Indulgence – Restraint (Hofstede) 51.29 21.7 Sig. (2-Tailed) NAL-Number of Active Languages (ln – SIL) Sig. (2-Tailed) November 22-23, 2015 Oxford, UK -0.458 3.1 1.44 -0.258 0.124 0.049 0.349 -0.429 0.247 0.848 0.001 0.059 0.000 -0.55 0.276 0.493 0.625 0.000 0.034 0.000 0.000 0.34 0.444 0.209 0.272 0.096 0.013 0.001 0.125 0.045 0.485 0.306 -0.048 0.238 -0.221 -0.145 0.073 0.019 0.720 0.063 0.084 0.259 0.596 14 0.596 1.000 13th Global Conference on Business & Economics TEA – Total Economic Activity Variable Constant Economic Freedom Index Kauffman Regulatory Quality Indulgence Individualism # of Active Languages (ln) World Bank Income Classification Entire equation R^2 Adjusted R^2 F Sig. df FFA - Fear of Failure Variable Constant Economic Freedom Index Kauffman Regulatory Quality Indulgence Individualism # of Active Languages (ln) World Bank Income classification Entire equation R^2 Adjusted R^2 F Sig. df November 22-23, 2015 Oxford, UK ISBN : 9780974211428 B 14.347 .253 -2.905 .123 -.105 1.060 -.883 Std. Err 5.914 .115 1.500 .032 .037 .512 1.344 Beta .384 -.392 .398 -.374 .245 -.094 t 2.426 2.202 -1.937 3.884 -2.794 2.072 -.657 Sig. .019 .032 .059 .000 .007 .044 .514 .526 .466 8.866 0.000 54 B 46.139 -.257 5.675 -.204 .030 -.204 -.705 .316 .273 4.519 0.002 54 15 Std. Err 10.628 .178 2.227 .049 .054 .049 1.956 Beta -.299 .586 -.507 .082 -.507 -.058 t 4.341 -1.441 2.549 -4.176 .558 -4.176 -.360 Sig. .000 .156 .014 .000 .580 .000 .720