Small Businesses Strategies in Times of Crisis: Empirical Evidence from the Province of Pesaro-Urbino

advertisement

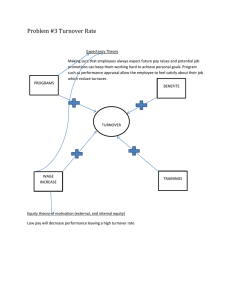

10th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9830452-1-2 Small Businesses Strategies in Times of Crisis: Empirical Evidence from the Province of Pesaro-Urbino1 Tonino Pencarelli – tonino.pencarelli@uniurb.it Simone Splendiani – simone.splendiani@uniurb.it Elisa Nobili – elisa.nobili@uniurb.it Abstract This work aims to understand the strategic behavior of small local businesses during the global economic crisis in the year 2009. The brief initial literature review on strategies related to the crisis identifies primary strategic behavior recognized by most authors as a response to the crisis. The authors then verify applications through a field survey, carried out on a sample of over 300 sectorally different small and micro enterprises affected by the crisis. The research shows a complex picture of the crisis, with uneven and varied dynamics. The strategic responses of Small Businesses are often defensive and aimed at reducing the impacts of the decrease in turnover and profit margins through rationalization and downsizing strategies. We emphasize, however, also cases of active response, such as growth through internalization or strategies aimed at redefining the business. 1. Introduction: from global crisis to company crisis According to many observers, the global crisis of 2008-2010 is configured as a cascade process, whose source was the bursting of the American housing bubble between 2005 and 2006. The collapse in property prices, partially due to the mishandling of so-called subprime mortgages, was added to the difficulties many American households had in honoring their debts and has prevented them from refinancing their mortgages. It was evidently the beginning of a period of serious and deep recession, marked by a contraction of real GDP, a significant and widespread drop in demand and, consequently, production and employment. This recession was caused not by companies but by consumersseverely affected by the decline in housing prices, stock price and jobs (Pellicelli, 2009). In the Marche region of Italy, in which the firms of our survey are located, the impact of the global crisis has proven to be very hard. In 2009 the regional GDP declined by about 6% more than the Italian average2. This affected certain characteristics of the regional economy, such as increased specialization in industry, fashion and durable consumer goods, the purchase earnings from which can be easily returned to families in times of crisis. According to data from the Bank of Italy, 1 The authors worked jointly on the paper. However, in the drafting phase, Simone Splendiani edited §1, Elisa Nobili §2 and Tonino Pencarelli §4. Simone Splendiani and Elisa Nobili edited §3. 2 www.prometeiadvisor.it October 15-16, 2010 1 Rome, Italy 10th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9830452-1-2 between autumn 2008 and the end of 2009 the region's exports contracted by about a third, double the national average, while there was a general decline in sales of industrial enterprises about 15%. For the purpose of our study is important to note that although the global recession - and consequently the regional one - has been an important factor in determining conditions of decline, for businesses the causes of the crisis appear to be very numerous and not easily decipherable. The business crisis can be observed as a process of deterioration of viability3, because of inadequate strategic approaches and clumsy corporate structure aggravated by external cyclical factors. Value destruction is not always so obvious but may be latent, potentially compromising the ability of the company to respond quickly and appropriately to the situation. In other words, deterioration may not emerge clearly for years, only to manifest itself in all its effects as the result of a triggering event - like an economic downturn (Cf. Guatri, 1995; Piciocchi, 2003; Sciarelli, 1995). The literature has questioned the factors behind the decline in business, and there and emerge two opposing lines of thought (Cf. Guatri, 1995). The first is subjective-behavioral, which indicates the human factor and management errors as the causes of decline. The second is objective, which recognizes the existence of some objective conditions that make the company vulnerable and then "ripe" for the crisis. In our opinion, the crisis is the consequence of the accumulation of unfavorable operating results due to the inability of the business and managerial skills to govern the complex relationships between the dynamics of external environmental and internal business. A crisis is therefore a result of adverse events both inside and outside the enterprise (Sciarelli, 1995). While external factors are largely outside the control of business, internal ones are related to specific organizational and strategic errors made by company management 4. Also according to Coda et. al. (1987) neither the managerial choices nor the environmental variables - alone - can account for a crisis. The initiation of a process of corporate crisis is due to inadequate entrepreneurial and managerial resources in relation to the complexity of the issues to manage5. According to this view of overlap between internal and external factors6, the incidence of 3 Guatri (1995) clarifies the meaning of "crisis" through the conceptual distinction between decline and crisis. According to the author, the conditions for the decline of a company emerging in terms of destruction of value of business capital and business is in decline when it loses value over time. These are not, therefore, decreases in planned return as in a historical decline but rather the loss of earning capacity. The crisis, from this point of view, is the further development of the decline and can only result in the death of the company. Although it is quite easy to imagine a decisive moment that determines the transition from crisis to decline, it is useful for our purposes to accept Sciarelli’s distinction (1995) between: • reversible state of acute crisis, when a crisis has become critical and causes serious impairment of business equilibrium without having reached the stage of irreversibility; • state of terminal crisis, however, occurswhen the situation of instability inevitably leads to bankruptcy or voluntary liquidation of the company. In other words, the company has spent its life cycle and is therefore affected by an irreversible crisis. 4 Among the internal factors, the author distinguishes between strategic mistakes (composition of the portfolio mix of investments), positioning (choice of segments and niche markets to serve); size: related to an imbalance between organizational capabilities and performance in terms productivity, cost and profitability of Inefficiency (related to an imbalance between cost and performance components of the combination of factors of production) 5 Cf. Amigoni (1997). 6 Cf. Hofer (1980), Bibeault (1982), Hambrick and Schecter (1983). Although these studies apply "internal / external causes" in their empirical dichotomy and highlight the need for strategic reorientation. October 15-16, 2010 Rome, Italy 2 10th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9830452-1-2 adverse external events on the business economy is very different depending on whether companies based their success on fragile foundations that will eventually collapse or, on the other hand, on well-designed, internally consistent, successful business formulas 7. The analysis of the context in which the company operates, however, may represent a starting point for understanding the crisis and the underlying causes8. The global crisis of 2008-2010 struck most economic sectors, even unrelated sectors and sectors that had historically not suffered during recessionary periods, such as the luxury sector. However, many areas - and many companies - have been strengthened during the crisis and this highlights the need for a specific analysis for individual sectors. Probably as very different situations emerge, there will be different opportunities to "reverse course" and then manage the decline (Cf. Harrigan, 1988). It is likely that some areas will come out of the crisis with new factors of competitiveness and new business models or renovated product technologies (Pellicelli, 2009). The objective of the paper is to analyze the strategic behaviour of firms after the impact of global crisis. This behavior is determined by pre-crisis business conditions, as is the intensity of the impact that the downturn has had on the sector to which they belong. The study is based on a questionnaire survey conducted on a sample of micro and small businesses (up 49 employees) located in the Province of Pesaro and Urbino, Marche in early 2010. The objective was to capture not only the strategies implemented in the months before (especially the second half of 2009, during the full-blown crisis) but also the actions foreseen in the short term (the first half of 2010) whose developments on the overall economic situation appeared very uncertain. The survey sample consists of 308 companies, about 8% of those registered at the Chamber of Commerce of Pesaro and Urbino. Stratified sampling is adopted by shares, according to the weight of the various productive sectors (agriculture, commerce, industry) of the total registered companies. The research presents a complex picture of the crisis, with uneven and varied dynamics. The strategic responses of Small Businesses are often defensive and aimed at reducing the impacts of the decrease in turnover and profit margins through rationalization and downsizing strategies. We emphasize, however, also cases of active response such as growth through internalization or strategies aimed at redefining the business. 7 Very interesting data t emerge from the report of Bank of Italy (June 2010) on the regional economy of the Marche Region, which was less exposed to the crisis as companies had begun restructuring in previous years. On the topic see also Rugiadini (1974), Booth S. (1993), G. Meyers, and Holusha J., (1988). 8 It is possible to distinguish between different situations (Sciarelli, 1995): a) industry/sector in structural crisis, a crisis that is likely to continue and, therefore, difficult to overcome without redefining the boundaries of the market served. In this case the crisis is also sectoral, and the subjective responsibility of managers are less pronounced; b) industry/sector in an economic crisis, with the possibility of a recovery in medium-short time without substantial change in its structure (and quantitative relationship between demand and supply); c) industry/sector in stationary situations. The crisis is mainly due to corporate affairs; d) growth industry/sector. Here again the crisis is rooted in the company, and is due to the inability to reach terms of efficiency and competitiveness in a market that expands over time. October 15-16, 2010 Rome, Italy 3 10th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9830452-1-2 The analysis reveals that the main reaction to the crisis is defensive, cutting unnecessary costs, investment bans and non-renewal of workers’ contracts are frequently used actions. However, there are cases of companies able to "look beyond the crisis”, to when the scenarios will be different and will probably change the rules by which to write new competitive strategies. 2. Business characteristics and impact of the crisis The companies studied are extremely diverse in terms of activities, legal form, size and number of employees. The sample is composed of 32% - industry, 31% - crafts, 20% - trade and the remaining 17% agriculture. The vast majority of firms, 71%, are micro-enterprises – MicroEs (up to 10 employees, based on definition given by European Commission), while others are considered small-enterprises- SEs, up to 49 employees. The companies concerned tend to develop their sales reports mainly at the provincial level, but extend nationally in both sales and procurement. We can therefore say that the sample consists of companies engaged in little business with foreign markets.9 The economic crisis has hit companies in the province of PU hard , particularly for employment. Our survey reveals that staff reductions concerned the 29% of sample firms (19% of MicroEs and 53% of SEs). The industrial sector was most affected (68%), while the least affected appears to be agriculture (problem not experienced by 98% of respondents). Trade and craft stands at 16% to 33% staff reductions. The study highlights in particular the use of layoffs (38%) and redundancies (26%), followed by remedies such as the reduction of the working day (17%) or working week (8%). 11% of respondents, however, claim to have used other means. All companies reported non-renewal of contracts. One of the primary purposes of the study has been to assess the competitive position of companies as perceived by managers or entrepreneurs themselves, as an important element for assessing the impact of the crisis and possible ways out. This is carried out through swot analysis. While quality standards and technical skills emerge first, other entrepreneurs perceived structural weaknesses such as high costs, limited commercial and managerial skills, financial weakness and in most cases the lack of international outlook. With reference to the external environment, firms indicate the presence of market niches and the possibility of alliances and partnerships as the greatest opportunities. A fair percentage of companies also noted the presence of growing markets. The biggest threat for companies, however, is represented by price wars. Fig. 1 - The SWOT analysis according to local entrepreneurs: a summary Strengths Weaknesses Quality standards High costs Technical skills Limited commercial and managerial skills Financial weakness Opportunities 9 Market niches accessible Threats On the topic see Gregori and Cardinali (2006); Schillaci (2005). October 15-16, 2010 4 Rome, Italy Price wars 10th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9830452-1-2 Strategic alliances The sample firms also possess certain characteristics common to small and micro enterprises, such as the lack of organizational and managerial skills, lack of attention to monitoring performance and, in general, a lack of strategic awareness (Pencarelli, Savelli, Splendiani, 2009; Cf. Pencarelli, 2009). All these represents a condition of vulnerability and risk. However, there are elements typical of small businesses - such as structural flexibility that may, on the contrary, be strengths of particular importance in times of crisis (Cf. Marchini, 1998; Faraci, 1996). Turning to financial data, study shows that for 42% of the sample turnover in the second half of 2009 was down compared to the first, turnover was constant for a further 42% , while it increased for 16%. The research shows that MicroEs recorded a higher percentage of turnover decrease. Fig. 2 - Turnover trends in the second half of 2009 As well as turnover, we also examined other indicators such as the firms' liquidity, debt turnover and changes in timing of collection and payment10. We found that: - Financial liquidity deteriorated from the first to the second half of 2009 - for 51% of the companies. It was stable for 42% of the companies, while it improved in 7% of the cases; Fig. 3 – Financial liquidity trends in the second half of 2009 10 On the topic see Metallo (2007). October 15-16, 2010 Rome, Italy 5 10th Global Conference on Business & Economics - ISBN : 978-0-9830452-1-2 Debt turnover - in the same period - was not altered for 51% of companies. It increased for 31% of the companies, decreased for 8% of them, and 10% of respondents said they had no share of debt; Fig. 4 – Debt turnover trends in the second half of 2009 - Timing of payment collection remained unchanged for 47% of companies and increased for 44% of them; Timing of payment remained unchanged for 45% of firms, although there is a significant percentage of firms for which it increased (43%). The survey also addressed the issue of the relationship between banks and companies, investigating the conditions of access to credit. This revealed significant differences between MicroEs and SEs. While the majority of the first (63%) states a substantial stability of credit conditions, SEs perceive a worsening in 61% of cases. Overall stability conditions prevail, albeit slightly, on the cases of worsening. This latter is due mainly to increasingly necessary guarantees, high costs and increased length of credit service processing. October 15-16, 2010 Rome, Italy 6 10th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9830452-1-2 Fig. 5 – Credit conditions trends in the second half of 2009 3. The strategic responses to the crisis Possible responses to a situation of decline can be grouped under three strategic categories 11: - Offensive strategies (or development strategies) - to improve the competitive position of the company. Typical examples are offering the same quality product at lower prices, seeking continuous product innovation , pre-emptive strikes into new market segments, etc.. Development strategies include both concentration within the sector in which the company operates, and diversification through which development is generated outside the sector. - Defensive and waiting strategies - to protect market position and competitive advantage. This response reflects the consideration of the crisis period as temporaryand due to external causes of a cyclical nature. Businesses that implement this type of response often cut investment and the recruitment of personnel, focus on traditional activities and new developments expected in the industry and competitors' moves. These strategies are usually adopted by companies that have a strong position in areas with average attractiveness may 11 Cf. Thompson et al. (2006); Pellicelli (2005); Pilotti (2005) and Dagnino (2005). A useful taxonomy of possible actions proposed by a turnaround plan is offered by Guatri (1995), whereby improvement measures can be implemented through: - Restructuring - when made in traditional product/market combinations and without substantial dimensional variations. This is carried out through the improved efficiency of inputs; - Conversion - the dominant aspect is the search for new product/market also depending on innovation and marketing; - Resizing - especially when the crisis comes from excess capacity, whether induced by forecast errors or fall in global demand; - Reorganization - when the focus of the intervention is relevant to the organizational aspects (redefining responsibilities, information system controls). October 15-16, 2010 7 Rome, Italy 10th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9830452-1-2 be due to modest growth or declines in demand or environmental factors that threaten to change the competition. - Strategies of contraction, which usually goes through two stages. First they try to improve efficiency by reducing costs, improving productivity, reducing staff, delaying investments, closing obsolete plants, while reducing inventory, reviewing all organizational procedures and abandoning products with low or negative profitability. If the situation remains difficult, they move to a second phase during which the company faces three options: to start a turnaround or reversal, compete to give up and put the company in position to sell or decide to leave the field and get out of the market, or finally bankruptcy or liquidation, (Pellicelli, 2005). The exit paths in this case can be fast - through the sale of its assets to another company or with the cessation of activities - or slow - through a strategy of disinvestment, or keeping the investment minimum and trying to maximize cash flow in the short term in preparation for a gradual withdrawal. This strategic orientation is typical of periods of economic recession and crisis when reports to the company management need to assess whether it is appropriate to reduce presence in a market segment or sector. Generally, the immediate behavior of the entrepreneur before the crisis is that of rejection and disbelief (cf. Mayers, 1988). Those responsible for taking decisions tend to minimize signals from outside and invite a change in analytical perspective, focusing more on the strengths of the company. They are gripped by a kind of block in operational decision-making, to the point of almost total inertia. Seeing the arrival of the recession - which was apparent in the financial crisis and general decline in demand - most companies tend to be prudent, to postpone investment decisions. This is the first phase described by Pellicelli (2009) and so-called “wait and see12. If we analyze the strategies adopted by firms during the crisis period, the first strategy implemented was the investment ban, preferring to adopt prudent behaviour. 84% of enterprises have not made significant investments in recent months13 - 86% of MicroEs and 78% of SMs. Fig. 6 – Investment trends in the second half of 2009 12 According to the author, the next step is policy responses. First, those of immediate and measurable need. At this stage liquidity is considered the top priority, and every choice is evaluated in terms of cash flow. The next step is to research new opportunities, marked by the ability to look beyond the crisis. 13 Regarding the remaining 16% of respondents, investments were mainly in plants (55%), followed by advertising (18%), increase capital (16%), and research and development (11%). October 15-16, 2010 Rome, Italy 8 10th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9830452-1-2 In addition to the investment ban, research has shown that in the short term, the predominant strategic behaviour by firms was defensive and prone to waiting (57%). Development/offensive strategies were implemented by 36% of businesses and strategies of contraction by 7%. In other words, this data confirms that companies preferred to engage in prudential and waiting strategies. Specifically, if we look at the data by company size, we see that SEs adopted development strategies in 2009 (but also those in the highest percentage adopted strategies to cut back, albeit with significantly lower incidence). Defensive strategies were implemented, especially among MicroEs. Fig. 7 - Strategic responses in the second half of 2009 The study reveals that the bigger companies (SEs) and those who most felt the need to reduce staff implemented contraction strategies. October 15-16, 2010 Rome, Italy 9 10th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9830452-1-2 Defensive and waiting strategies, however, were adopted mainly by smaller companies (MicroEs) and members of the agricultural sector. These, not surprisingly, are also the firms that experienced fewer problems of employment-reduction despite having recorded a contraction in turnover. Companies that had shown an attitude toward development objectives tend to do so not only by adopting cost-containing strategies, but also by making new investments, entering new market niches and exploiting new technologies. This is the case of firms belonging to the craft sector but also of larger and businesses who have not felt the need to reduce staff even though they have also experienced a decline in turnover. Fig. 8 – Strategy-based profile of companies in 2009 Strategies of contraction - They belong to the industrial sector and they are the bigger companies (SE) - They tend to have felt the need to reduce staff in 2009 - In the second half of 2009 they showed constant or declining turnover and have made investments - These companies have had constant turnover in 2010 - The strategic focus for 2010 is aimed at reducing costs; - They identify quality as the main element of strength the and as high cost the main element of weakness - They identify partnerships and alliances as the main opportunities and price wars as a threat - - Defensive and waiting strategies They belong to the agricultural sector and they are smaller companies (MicroEs) They tend not to have felt the need to reduce staff in 2009 In the second half of 2009 they showed a decrease in sales but they have made investments These companies have had constant turnover in 2010 The strategic focus for 2010 is clearly aimed at cutting costs For these companies, quality is a strength while high cost are an element of weakness They identify the presence of market niches and alliances and partnership as the main opportunities, while as price wars a threat Development strategies They belong to the handicraft sector and they have between 10 and 49 employees (SE); They tend not to have felt the need to reduce staff in 2009 In the second half of 2009 they showed a decrease in turnover, but a good percentage of them have made investments These companies have had constant turnover in 2010 The strategic focus for 2010 is aimed at reducing cost (but in lower percentages), improving of production processes and quality of work, entering new markets and innovation They identify quality as a primary strength and high cost as a weakness The main opportunities are represented by available market niches while price wars are the primary threat. 4. Conclusions Economic history teaches that after every recession there is a recovery. This can be fast or slow, may be linear or have irregularities, may occur first in some countries than others or in some sectors than others. To state that there will be a recovery from the global crisis of 2008-2010 - as many observers expect - is not enough for an entrepreneur or manager. It is important to understand what October 15-16, 2010 Rome, Italy 10 10th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9830452-1-2 will change after the crisis and seize the opportunities that inevitably arise. As Pellicelli suggests (2009), there are four rules to follow in this period of uncertainty: to be informed; to be able to resist - those who in the past have prepared their organizations to withstand shocks; to be flexible – i.e. increase the portfolio of viable options, and - above all – to be able to look beyond the crisis in the awareness that every crisis brings new opportunities for those who will take (Cf. Baccarani and Golinelli, 2006). Research shows many internal constraints related to small size, such as the scarcity of financial resources and an entrepreneurial culture resistant to change and innovation. Moreover, the strategic paths of local businesses are also hampered by the inability of the entrepreneur to assess the business situation properly, sometimes overestimating, others underestimating. In other words, it appears difficult to sort and arrange the available information in a clear conceptual map in order to capture the signals of the competitive environment and develop a coherent strategy to it. These characteristics are especially exacerbated by global climate of uncertainty. The economic crisis has fallen on this business environment, affecting most of the companies under investigation. In fact, most of them showed problems with surplus staff, reduced turnover, investment bans, financial imbalances and increasing difficulties in accessing credit. Observed enterprises reacted predominantly with defensive and waiting behavior, especially micro enterprises (MicroEs). In particular, an analysis of the second half of 2009 shows that micro-enterprises (MicroEs) have felt less need for staff reductions than small companies - SEs (19% vs. 53%), probably because they already enjoy conditions of high production efficiency. This also shows that MicroEs are less affected by the worsening of financial liquidity and debt turnover. This can be justified by the investment ban policies that they have opted. Small enterprises, in contrast, show that financial indicators deteriorated in the short term but also a greater propensity for new investment. Analysis of future strategic orientations ( provided for the first half of 2010) shows that despite the fact that cost reduction still emerges as a strategic priority, the achievement of efficacy-based objectives takes precedence over those of production efficiency. Grouping the actions planned for 2010 into two basic perspectives - effectiveness and efficiency - we observe that 60% of companies give priority to qualitative growth by adopting a long-term prospective. Examples include the improvement of production processes and quality of work, entry into new markets, improving the quality of products / services and intervention on prices. The remaining 40%, however, prefers efficiency targets, focusing on cost reduction, downsizing and streamlining of all elements not considered strategic to their business. The research has important limitations related to the smaller size of the area under investigation and the impossibility of assessing the temporal evolution of crisis and business strategies, which would have required a reference period of at least 3-5 years. However, the study shows a highly differentiated and complex picture about the strategic responses to the crisis. On one hand, business reacted mainly with defensive and waiting strategies, often forced by the limits of size and financial nature. On the other hand, there is a tentative ability to look beyond the crisis, triggering processes of reorganization and quality improvement, although this is not adequately supported by new investments. October 15-16, 2010 Rome, Italy 11 10th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9830452-1-2 This study shows that business strategies in times of crisis are influenced both by the impact this has on their business - not all sectors are affected by the crisis with the same intensity - and by all resources and capabilities possessed by the enterprise, often related to its size. Thus small enterprises (SE) are those with the strategic flexibility, organizational flexibility, responsiveness and ability to strategically reorient towards development. All of these attributes are necessary to overcome the crisis but are not always owned by micro-size enterprises (MicroEs) (Cf. Ferrero, 1992. In light of this, the European Union should promote policies to support growth processes in small businesses. In particular, it is through integration programs and strategic alliances that small businesses may be able to acquire increasingly qualified resources, skills and abilities with which to successfully overcome the crisis (Pencarelli, 1995). Bibliography Amigoni F. (1977), Il controllo di gestione e le crisi d’impresa in AA.VV. “Crisi d’impresa e sistemi di direzione, Egea, Milano Baccarani C., Golinelli G.M., 2006, L'imprenditore tra imprenditorialità, managerialità, leadership e senso del futuro, Sinergie rivista di studi e ricerche, vol. 71 Banca d’Italia, Economie regionali, L’economia delle Marche, giugno 2010 Bertoli G., 2000, Crisi d’impresa, ristrutturazione e ritorno al valore Booth S., (1993), Crisis management.Competition and change in modern enterprises, T.J. Press Ltd, London Coda V., Bruni G., Sorci. C., Brunetti G., 1987, Crisi di impresa e strategie di superamento, Giuffrè Editore, Milano Bibeault D.B., 1982, Corporate Turnaround: How Managers Turn Losers into Winners, McGrawHill, New York Dagnino, G.B., 2005, I paradigmi dominanti negli studi di strategia d’impresa. Fondamenti teorici e implicazioni manageriali, Giappichelli, Torino Faraci R., 1996, Razionalità strategica e percorsi di sviluppo delle imprese minori, CEDAM Ferrero G., 1992, Struttura, strategia e processi innovativi nelle piccole imprese, Lint Editore, Trieste. Gregori G.L., Cardinali S., 2006, Aziende agricole e relazioni commerciali: aspetti cognitivi e competenze richieste", AgriRegioniEuropa, settembre Guatri L., 1995, Turnaround. Declino, crisi e ritorno al valore, EGEA, Milano. Hambrick D., Schecter S., 1983, Turnaround Strategies for mature industial products”, Academy of management journal, n. 26 Harrigan R., 1988, Managing maturing businesses: restructuring declining industries and revitalizing troubled operations, Lexington Books, Lexington. Hofer C.W., 1980, Turnaround strategies, Journal of Business Strategy, n.1 . Marchini I., 1998, Il governo della piccola impresa, vol. I, ASPI/INS-EDIT, Genova. Metallo G., 2007, Finanza sistemica per l’impresa, Giappichelli, Torino. October 15-16, 2010 Rome, Italy 12 10th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9830452-1-2 Meyers G. C.,1998, Gestire le crisi – come affrontare e risolvere le difficoltà dell’azienda, IlSole24Ore, Milano Meyers G., Holusha j., (1988), Managing Crises: a positive approach, Unwin, London Pellicelli G., 2005, Strategia d’impresa, Università Bocconi Editore, Milano. Pellicelli G., 2009, Management ritorno al futuro. Strategie aziendali per accanciare la ripresa, Egea, Milano Pencarelli T., 2009, La performance strategica in Di Bernardo B., Gandolfi V., Tunisini A. (a cura di), Manuale di economia e gestione delle imprese, Hoepli. Pencarelli T., 1995, Piccola impresa, alleanze strategiche ed integrazione europea, Aspi/Ins-Edit, Genova. Pencarelli T., Savelli E., Splendiani S., 2009, Strategic awareness and growth strategies in Small Sized enterprises (SEe) International Journal of Business & Economics, Vol.8, n.1 Piciocchi P., 2003, Crisi d’impresa e monitoraggio di vitalità. L’approccio sistemico vitale per l’analisi dei processi di crisi, Giappichelli, Torino Pilotti L., 2005, Le Strategie dell’ Impresa, Carocci, Roma Rugiadini A., 1974, La pianificazione dell’impresa. Aspetti metodologici e organizzativi, F.Angeli, Milano Schillaci C.E., 2005, Le relazioni strategiche tra multinazionali e imprese locali: Analisi empirica di un sistema locale di imprese nel settore microelettronico, Economia e politica industriale , n.124 Sciarelli S., 1995, Crisi d’impresa, Cedam, Padova Thompshon A., Strickland A.J., Gamble J. E., 2006, Crafting & Executing Strategy, Mc Graw Hill/Irwin. October 15-16, 2010 Rome, Italy 13