CheniPOPY3Muni

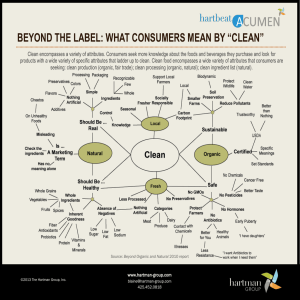

advertisement