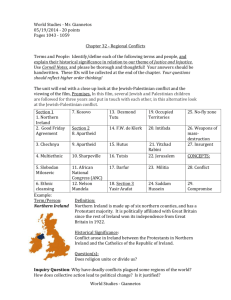

esdp00-01_donohue.doc

advertisement