Chap 1 ppt

advertisement

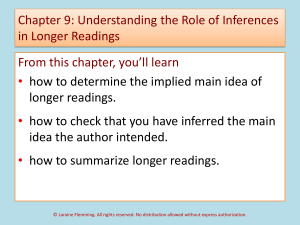

Chapter 1: Strategies for Textbook Learning From this chapter, you’ll learn 1. about SQ3R, a tested and flexible system for reading textbooks. 2. the importance of “reading flexibility.” 3. how reading rate should be adjusted to text and purpose. 4. how the World Wide Web can be used to improve comprehension. Copyright Laraine Flemming 2009 1.1 Using SQ3R: A System for Studying SQ3R stands for 1. Survey the chapter to get an overview. 2. Question to focus concentration. 3. Read to answer the questions. 4. Recall to test your understanding. 5. Review to see how all pieces fit together. Copyright Laraine Flemming 2009 1.1 Survey to Get an Overview To survey, read the following: 1.Title and Introductory material 2.Headings and opening sentences of chapter sections 3.Visual aids such as pictures, charts, graphs, tables, and highlighted words 4.End-of-chapter summaries and questions Copyright Laraine Flemming 2009 1.1 Survey Goals The Four Goals of a Survey Are 1. to get a general overview of the material. 2. to get a feel for the writer’s style. 3. to get a sense of what’s important. 4. to identify breaks in the chapter. Copyright Laraine Flemming 2009 1.1 Step 2: Ask Questions for Focus Using questions to guide your reading can help you • remain mentally active while reading. • maintain your level of concentration. • keep you alert to key passages in the chapter. Copyright Laraine Flemming 2009 1.1 How to Form Questions Your questions can be based on • headings, key words, pictures, or graphics in the chapter. • comparisons to other writers on the same subject. • your own personal experience. Copyright Laraine Flemming 2009 1.1 Step 3: Read in Chunks When you read a textbook, remember to • read it in chunks of no more than 10 or 15 pages. • write while you read. • periodically paraphrase, or sum up in your own words, what you have just read. • vary your assignments whenever you are studying for more than two hours. Copyright Laraine Flemming 2009 1.1 Write while Reading Writing while reading is critical because it helps you 1. remember what you read. 2. check your comprehension. 3. maintain concentration. Copyright Laraine Flemming 2009 1.1 Write while Reading Use any or all of these writing strategies: • Underline key words in sentences. • Use boxes, stars, and circles to highlight key names and dates. • Take marginal notes, jotting down central points. • Mark important passages with double bars, stars, or asterisks. • Identify, perhaps with a “P, ” ideas for papers. Copyright Laraine Flemming 2009 1.1 Step 4: Recall after Completing a Chapter Section Recalling right after reading can be done in a number of ways. You can 1. mentally recite the general point and a few details. 2. write out answers to questions you posed during your survey. 3. cover up and try to recall parts of your outline. Copyright Laraine Flemming 2009 1.1 Step 4: Recall after Completing a Chapter Section You can also 1. make rough diagrams or drawings. 2. ask a classmate to quiz you on the material. 3. use any other method you can think of to see how much you remember. Copyright Laraine Flemming 2009 A Word to the Wise The rate of forgetting is fastest right after you finish reading. Recalling by repeating what you just read in your own words slows down the rate of forgetting so you forget less. Copyright Laraine Flemming 2009 Another Word to the Wise As soon as you start a study session, identify how many pages you plan to read. This is particularly important if you are reading a long chapter. Chopping the chapter into several ten- or fifteen-page assignments will make it seem more manageable, and you won’t give up on it. Copyright Laraine Flemming 2009 1.1 Step 5: Review Right After Completing the Chapter The review step of SQ3R • takes place right after you finish the entire assignment. • focuses on how parts of a text fit together to develop a general point. • should either confirm or force you to revise some of your initial predictions about a chapter or article. Copyright Laraine Flemming 2009 1.1 The Goals of the First Review Reviewing right after you complete the assignment • helps anchor new information in your memory. • gives you a sense of what passages might need a second reading. • lets you focus more on the overall objective, or point, of the material Copyright Laraine Flemming 2009 1.1 Methods of Review 1. Look at all the major headings and try to recall the general point introduced. 2. Work with a friend who asks you questions about the headings. 3. Use the headings to make an outline and write down what you remember about each one. Copyright Laraine Flemming 2009 1.1 Create Diagrams that Highlight Relationships Among Parts of the Chapter The unfair taxation imposed by the British The rise of the merchant middle class in the colonies The forced quartering of British soldiers in American homes and inns Three central factors aroused American fury against British rule and contributed to the Revolutionary War Copyright Laraine Flemming 2009 A Word to the Wise Few strategies for reading—and for that matter for life—apply to every single situation. Adapt your reading strategies to the material. For instance, if you’re reading a passage that has strong visual imagery, take notes with diagrams or drawings. However, switch to an outline if you think the material doesn’t easily lend itself to pictures. In other words, BE A FLEXIBLE READER, changing strategies to suit the material. Copyright Laraine Flemming 2009 A Word on Multi-Tasking Copyright Laraine Flemming 2009 Don’t Do It While Studying ! Copyright Laraine Flemming 2009 Staying Focused is Essential None of the techniques for mastering your textbooks will be effective if , while studying, you are texting and checking your cell, RSS feed, or Twitter. Here’s what one of perhaps twenty studies has to say on the subject of multi-tasking. And for the record, they all say pretty much the same thing: Copyright Laraine Flemming 2009 Multi-Tasking and Studying Don’t Mix According to a group of Stanford University researchers, multi-taskers are “suckers for irrelevancy. Everything distracts them.” The Stanford researchers say that the more people multi-task, the more they lose the ability to separate the significant from the insignificant. The results of the study are currently available at stanford study. Copyright Laraine Flemming 2009 1.3 Reading Rate and Reading Flexibility Make it a point to vary your reading rate depending on 1. the difficulty of the material. 2. your level of familiarity with the author’s ideas. 3. your purpose in reading. Copyright Laraine Flemming 2009 1.3 Reading Rate and Reading Flexibility • For a survey, feel free to skim at high rates of speed like 600-800 words per minute. • For understanding easy-to-read and moderately familiar material, slow down to 300-400 words per minute. • For pages of moderate difficulty, maintain a speed of 200-250. • For hard-to-read and unfamiliar material, slow down to around 150-200 words per minute. Copyright Laraine Flemming 2009 What’s the moral of this story? There’s an old Woody Allen joke that goes like this: “I took a speed reading course and read War and Peace. It involves Russia.” War and Peace is set in Russia. It is around 900 pages long. What point did Allen want to make about speed reading? Copyright Laraine Flemming 2009 A Word to the Wise It might surprise you to hear that reading too slowly can be as ineffective as reading too quickly, in part because reading the assignment can take so long, it becomes agonizing. Slow your rate way down only when you feel completely lost. Otherwise push yourself to keep going at around 200-250 words per minute. If a passage doesn’t seem completely clear, mark it for re-reading (RR). And make sure you really do re-read. Copyright Laraine Flemming 2009 1.4 Using the World Wide Web for Background Knowledge The more you know about a subject, the easier it is to comprehend what you read. When you are starting a chapter dealing with an unfamiliar topic, use the Web to get some basic background knowledge. Copyright Laraine Flemming 2009 1.4 Using the Right Search Term When it comes to getting background knowledge from the Web, the right search term is critical. A good search term should (1) take into account the chapter purpose and headings, (2) be focused and specific rather than broad and general, and (3) usually be a phrase rather than a single word or name. Copyright Laraine Flemming 2009 1.4 What’s the Right Search Term? Your search term should 1. be influenced by the headings in the text. 2. be specific enough to exclude topics you don’t care about. 3. be phrases rather than single words. Copyright Laraine Flemming 2009 1.4 Picking the Right Search Term Imagine that you are surveying a chapter about the history of the Supreme Court, and you run across the heading “The Origins of Judicial Review.” If you want some background knowledge about that topic, which of these search terms would be more useful to you? Copyright Laraine Flemming 2009 1.4 Picking the Right Search Term 1. History of the Supreme Court 2. Judicial Review 3. Supreme Court and Judicial Review Copyright Laraine Flemming 2009 1.4 Focusing Your Search Term Although you could probably get background knowledge for the chapter with all three choices, the fastest would be the “Supreme Court and Judicial Review.” Copyright Laraine Flemming 2009 1.4 Focusing Your Search Term 1. The “History of the Supreme Court” would take you in too many irrelevant directions. You want to know about judicial review in relation to the Supreme Court, not all about the Supreme Court past and present. This search term would give you too many sites you couldn’t use. 2. “Judicial Review” would get you right to a definition of the term. However, given that you are reading a chapter on how the Supreme Court evolved, or developed, you want to know how judicial review came into being as part of the Supreme Court’s history. Copyright Laraine Flemming 2009 Just So You Know Judicial Review is the right of the Supreme Court to review and, if need be, challenge existing legislation created at the state or federal level. It also means that the Supreme Court has the right to review decisions made by the president. The Supreme Court’s right to judicial review came into being as a consequence of the case Marbury v. Madison (1803), which set a powerful legal precedent, or pattern, for future decisions. Copyright Laraine Flemming 2009 Finishing Up: Strategies for Textbook Learning You’ve previewed the major concepts and skills introduced in Chapter 1. Take this quick quiz to test your mastery of those skills and concepts, and you are ready to read the chapter. Copyright Laraine Flemming 2009 Finishing Up: Strategies for Textbook Learning See how well you can describe each of the steps in SQ3R. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. S Q R R R Copyright Laraine Flemming 2009 Finishing Up: Strategies for Textbook Learning 6. What factors should decide the rate at which you read? 7. What is reading flexibility? 8. How can the World Wide Web help your read textbooks? 9. What are the three characteristics of a useful search term? Copyright Laraine Flemming 2009 Finishing Up: Strategies for Textbook Learning 10. Imagine that you were getting ready to read a chapter titled “The Growing Problem of Consumer Debt, “ and it was forty pages long. What’s the first thing you should do and why? Copyright Laraine Flemming 2009 Brain Teaser Challenge Copyright Laraine Flemming 2009 Brain Teaser Challenge: There’s no right or wrong answer to this question, only answers that do or do not make a connection: How does what you have just learned from these slides relate to this line from a poem by Emily Dickinson? “I’ve known her—from an ample nation— choose one—Then—close the valves of her attention—like stone.” Copyright Laraine Flemming 2009