Policy and Practice Implications for Secondary and Post-Secondary Education and Employment for Students with Disabilities

advertisement

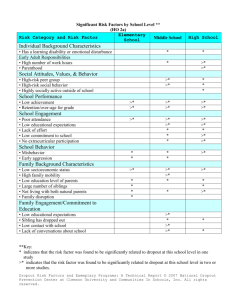

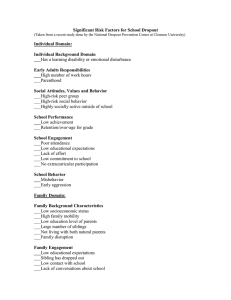

A National Leadership Summit on Improving Results for Youth Policy and Practice Implications for Secondary and Postsecondary Education and Employment for Youth With Disabilities September 18 and 19, 2003 Washington, DC Improving Graduation Rates Through Dropout Prevention Strategies That Work Camilla (Cammy) Lehr National Center on Secondary Education and Transition Institute on Community Integration University of Minnesota September, 19, 2003 NCSET Leadership Institute Preventing Dropout: A Critical and Immediate National Goal Approximately 1 in 8 children in the United States never graduate from high school (Children’s Defense Fund, 2001) Based on calculations per school day, one high school student drops out every nine seconds (Children’s Defense Fund, 2001) Recent statistics representing the percentage of eighth grade students who graduate five years later range from a low of 55% in Florida to a high of 87% in New Jersey (Greene, 2002) Current Data on Exit Dropout Rate for Students Served Under IDEA, Part B for school year 2000-2001 (OSEP) 29% of students with disabilities dropped out of school Rate based on number of students ages 14-21 leaving school “Dropped out” is defined as the total who were enrolled at some point in the reporting year and were not enrolled at the end of the reporting year. Category includes dropouts, runaways, GED recipients, expulsions, status unknown and other exiters. Current Data on Exit This rate (29%) compares with 34% for the 1995-96 school year Highest rate of dropout for students with disabilities by state is 70% (Hawaii) 28% of students with learning disabilities; 53% of students with emotional disturbance dropped out Highest rate of dropout by race/ethnicity for students with disabilities is 41% for American Indian/Alaska Native Added Impetus for Addressing Dropout Significant costs to individuals who do not complete school Significant costs to society No Child Left Behind holds schools accountable for student progress using indicators of adequate yearly progress including measures of academic performance and rates of school completion Students with disabilities are required to participate in standards based reform and accountability systems 27 states are in the process of implementing high stakes assessments used to determine whether students can graduate from school with a regular diploma The Question What do we know that is research based and how can that information be used to inform practice and improve graduation rates? Five Strategies Establish Procedures to Accurately Measure Rates of School Completion Need for consistency in definition Formulas for calculating dropout vary and commonly yield Annual rates Status rates Cohort rates Comparisons across time and student groups may yield faulty interpretations Dropout rates do not simply or directly translate to an accurate graduation rate Impact of mobility on tracking students accurately Increased awareness of the issues will assist in developing sound procedures for measuring progress Identify Students Who Are Placed At Risk Based on Multiple Variables Variables associated with dropout have been categorized according to the extent to which they can be influenced to change the trajectory leading to dropout Status variables are unlikely to change (e.g. socioeconomic standing, disability, family structure) Alterable variables are more amenable to change and can be influenced by students, parents, educators and community members Alterable variables identified for students with disabilities include high rates of absenteeism, course failure, low participation in extracurricular activities, negative attitudes towards school, alcohol or drug problems). Presence of multiple factors increases the risk of dropout Implement Interventions Designed to Address Alterable Variables School level alterable variables associated with school completion for students with disabilities (Wagner, Blackorby & Hebeler, 1993) Providing direct, individualized tutoring and support to complete homework assignments Support to attend class, and stay focused on school Participation in vocational education classes Participation in community based work experience programs and training for competitive employment Push effects – situations or experiences within the school environment that aggravate feelings of alienation, failure and dropout (e.g., raising standards without providing supports, suspension, negative school climate) Pull effects – factors external to the school environment that weaken or distract from the importance of school completion (e.g., pregnancy) Ground Interventions in a Sound Conceptual Understanding of Dropout Dropping out of school is a process of disengagement that begins early Theoretical conceptualizations have pointed to the important role of student engagement in school and learning (participation, identification, social bonding, personal investment in learning) Engagement is a multi-dimensional construct involving associated indicators and facilitators (academic, behavioral, psychological) A focus on enhancing students connection with school and facilitating successful school performance is a promising approach for improving school completion. Current Conceptualizations of Dropout to Inform Intervention Design and Implementation School completion encompasses a broader view than simply preventing dropout. Interventions that promote school completion are characterized by: A strength based orientation Comprehensive interface of systems Implementation over time Meeting individual needs by creating a personenvironment fit A focus on promoting a good outcome, and building skills – not simply preventing a bad outcome Addressing core issues associated with student alienation and disengagement from school Identify Interventions that Show Evidence of Effectiveness There is not one best program “It is unlikely that a program developed elsewhere can be duplicated exactly in another site, because local talents and priorities for school reform, the particular needs and interests of the students to be served, resources available, and the conditions of the school to be changed will differ.” (McPartland, 1995) Consider examples in relation to the needs, demographics, resources and other circumstances of local schools or districts. Claims of effectiveness must be supported by adequate research and/or evaluation Recent efforts are focused on beginning to identify key components across programs that are effective in promoting school completion (e.g. persistence, relationships, monitoring progress)