adrian & delibes 1987_ j_zool lond.doc

advertisement

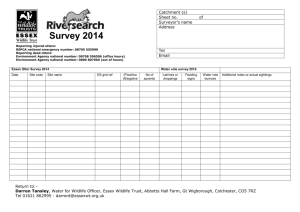

Food habits of the otter (Lutra lutra) in two habitats of the Doflana National Park, SW Spain M. I. ADRIAN AND M. DELIBES Estacibn JJio!ôgica de Doñana, CSIC, Apdo. 1056, 41080 Sevilta, Spain (With 3 figures in the text) Food habits of otters Lutra lutra were studied in two localities of the Doflana National Park (SW Spain) 16 km apart. These were the lowest stretch of Arroyo Rocina, a eutrophic stream where American red-swamp-crayfish were introduced in 1976, and at Lucio Bolin, an artificial pond 150 m in diameter, situated on the border of the Ouadalquivir marshes. In all, 598 spraints were analysed between 1979 and 1984. Crayfish, occurring in 80% of the spraints, was the dominant food item in Arroyo Rocina, where other common foods were fish (63%), insects (55%) and amphibians (18%). Fish, occurring in 94% of the spraints, were by far the most abundant food item in Lucio Bolin, followed by insects (32%) and amphibians (28%). Seasonal differences in diet were small but interesting: reptiles were eaten more often in the dry season (April—September) and insects and crayfish in the rainy season (October-March). Among fish, eels were more commonly eaten in the rainy period and the remaining species in the dry period. This pattern of seasonal variation is opposite to the usual in temperate Europe. Mean size of the captured eels was statistically higher in Lucio Bolin than in Arroyo Rocina. A large amount of very small fish such as Gambusia was eaten. A comparison of prey consumed with estimates of prey abundance reveals a strong preference for eels. The diet of Mediterranean European otters seems to be more diverse than that of northern European ones, including more insects, amphibians and reptiles. Contents Page Introduction Study area Material and methods.. Results Otter diet in both habitats Seasonal variation Prey size Notes on prey choice Discussion References . . .. . . . . . 399 400 401 401 401 403 403 404 405 406 Introduction Most of the work on otter (Lutra tiara) diet has been done in temperate climates. This paper reports on the food habits of otters in the Guadalquivir marshes (Doflana National Park), a Mediterranean area of south-western Spain at sea level (Fig. 1). The paper aims to describe the FIG. I. Map of the Doflana National Park and surroundings showing the three main biotopes (shading indicates marsh) and both study localities. R = Arroyo Rocina; B = Lucio Bolia. foods eaten by the otter in two zones of the Park, to analyse the diet variation between the wellmarked dry and rainy season, to identify the prey size ranges, with special attention to eels (Anguilla anguila), and to compare the relative abundance of prey in the habitat and in the otter diet. Study area At the Dofiana National Park, the summers are warm and dry and the winters mild and wet. Average annual rainfall is c. 500-600 mm, 87% falling between October and April. We collected otter faeces (spraints) at the lowest stretch of Arroyo Rocina (called Rocina), where otters live pennanently, and at Lucio BolIn (called BolIn), an artificial pond which was occupied by otters during at least 10 months in 1980-81. Rocina is eutrophic and flows through woodland dominated by Salix and marsh vegetation. In summer, the stream is reduced to a few pools with permanent water. Six species of fish have been recorded and water birds, amphibians, aquatic reptiles, introduced American red-swampcrayfish (Procambarus clarkii and ‘Procambarus acutus) and large diving beetles (Dytiscidae, Hydrophillidae) are very common. Bolin, a permanent artificial pond 150 m in diameter on the border of the marsh, approximately 16 km south of Rocina, is connected to a small 300 m long water course which passes through thick vegetation of Salix spp., Populus atba, Rubus ulinifolius, etc. BolIn is mostly open water, with a fringe of Typha latifolia, two islets and some patches of Scirpus spp. Some eels, Gambusia, loaches (Cobitis paludicola) and carp (Cyprinus carpio) moved into the area naturally, but eels and carp are aiso introduced occasionally. Water birds and reptiles, amphibians and large diving insects arc abundant. Red-swamp-crayfish were introduced in the Guadalquivir marismas in 1974 and now thrive. They colonized Rocina in 1976 and Bolin in 1983-84, three years after our sampling period. Thus, this study could be considered a comparison of the otter diet before (Bolin) and after (Rocina) the crayfish introduction in the area (Delibes & Adrian, In prep.). Material and methods Five hundred and ninety eight spraints were analysed in 1979-1984, 334 from Bolin and 264 from Rocina. In BoRn and Rocina, 147 and 119 spraints were collected in the dry season (April-September) and 187 and 145, respectively, in the rainy season (October—March). The results are presented as number of occurrences ( = number of spraints containing each prey group) and frequency of occurrence ( = number of occurrences of a prey x 100/number of spraints in the sample). This method does not accurately reflect the weight of ingested material (e.g. Wise, Liun & Kennedy, 1981) but it is quick arid simple and gives a good guide to the relative importance of the various items in the diet of otters (Erlinge, 1968; Rowe-Rowe, 1977). Numbers of occurrences of each prey in different samples (i.e. seasons, habitats, etc.) were compared by ax2 test. The size (in cm) of the eels consumed was estimated from vertebrae size following Wise (1980). Mean sizes were compared with a Student t test. Data from commercial fishibg. and scientifically oriented fishing in Rocina allow us to compare the relative abundances of different fish species in the habitat and in otter faeces. Results Otter diet in both habitats At Bolin, fish occurred in 943% of spraints (Table I). Other main items included insects (323%), amphibians (28l%) and reptiles (72%). Other foods were thought to be accidental. Eels were the most common fish recorded, followed by Gambusia. Carp and loathes occurred occasionally. Some insects (and most other invertebrates in BolIn) were probably the prey of the fish or amphibians Q’Jovikov, 1956). However, since most insects found in the spraints were large aquatic beetles (as large as 5 cm in the case of Hydrous piceus), we considered them to have been direct prey. Most amphibians were unidentified, but as many as six species, including some toads (Bufo sp.), were recognized, with marsh frogs (Ranaperezi) most common. No tailed amphibians were found. All reptiles eaten were viperine snakes (Natrix maura). Mallard (Anasplatyrhynchos) remains occurred in one spraint. TABLE I Frequency of occurrence of each food category in the spraints of the study areas n Lucio Bolin 334 spraints Arroyo Rocina n = 264 spraints ‘.9 Oryctolagus cuniculus Microtu duodecimcostatus Unidentified mammal 00 00 06 Anus platyrhynchos Gatlinula chiorapus 03 Unidentified small bird 03 1•1 08 0•0 08 00 04 08 71 00 Natrix maura Malpololl monspessulanus AMPHIBIANS Rana perezi Discoglossus picKus Pelobates cultripes Pelodyte pl4nctatus Hyla meridionalis Bufo sp. Unidentified anuran Snails Mussels 96•5 367 348 136 76 3S 565 4.5 122 0’O 342 803 8O3 558 132 21-0 Large diving beetles Other and unidentified SPIDERS MOLLUSCA 5.3 04 O8 00 0•0 04 I14 801 CRUSTACEANS INSECTS 3.3 09 12 03 06 O6 214 1533 Angidila anguilla Gambusia affinic Cobitis paludicola Cyprinus carpio Mcropterur salmoides Procambarus spp. 04 04 3-3 3-0 04 527 3-1 0-4 9-4 04 0-0 Red-swamp-crayfish occurred in 80-3% of the faeces from Rocina (Table 1). Other frequent items were fish (9&5%), insects (558%) and amphibians (18-3%). Mammals occurred in F9% of the 264 spraints examined. As in Bolin, eels and Gambusia were the most frequently recorded fish, followed by loaches and carp. Blackbass (Micropterus sairnoides), a species not found in Bolin, was recorded in 3-8% of the samples. Most insects were large diving Coleoptera (Cybister sp., Hydrous sp., etc.), presumably captured directly by the otters. Among the amphibians, marsh frog was the dominant species. Rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) remains occurred three times, Mediterranean pine vole (Micro(us duodecimcosrcuus) twice and moorhen (Gallinula chloropus), viperine snake and Montpellier snake (Malpolon monspessulanus) once each. 100 80 60 40 20 0 0 20 40 60 80 100 Frequency of occurrence Ftc. 2. Frequencies of occurrence of crustaceans (CR), insects (IN), fishes (FS), amphibians (AM) and reptiles (RP) in the spraints collected in two localities and two seasons on the study area, a dry season; rainy season. Besides crayfish, oniy present in one locality, other prey show statistical differences in their frequencies of occurrence in Bolin and Rocina. Fish (x2 = 974; P.cto’OOl), amphibians (x2 = 8’OS; P<OO1) and reptiles (2 = 14’65; P<O’0O1) were eaten more frequently in Bolin, where crayfish did not exist, while insects = 2998; P<000l) were a more important food item in Rocina. Seasonal variation Figure 2 compares frequencies of occurrence of each high category of prey at the study zones, in both the dry and the rainy seasons. The difference in diet between both periods is small. There were statistical differences at Bolin in frequency of occurrence of reptile remains (consumed more often in the dry season; x2 = P<O’Ol), and in Rocina of insect (x2 = 129, P<O’Ol) and crayfish (x2 = 355, P<006) remains, more important in the rainy season. At Rocina, mammals, birds and reptiles were recorded only in the dry season. Eels were more frequent in both localities in the rainy season (Bolin: x2 = 16’Ol, P<OMO1; Rocina: x2 = 8’29, P<O’Ol), while most other fish species occurred more frequently in the dry season (carp, Bolin: x2 = &07, P<OO1; carp, P<O’Ol; loaches, Rocina: x2 = 1651, P<O’OOl; Gambusia, Rocina: x2 = Rocina: x2 = 333, P<OO6). Prey size Prey size ranged from c. 1 g, in the case of some beetles and Gambusia, to c. 1 kg, in the case of some rabbits. Figure 3 shows the estimated size distributions of eels in spraints from Rocina and Bolin. In both places, the distribution was approximately normal, which suggests that otters also took animals of intermediate sizes. Nevertheless, the mean size was statistically higher at Bolin (mean 36’S em, range 15-58 cm) than in Roeina (m = 24’3, r 10-54) (P<OO01). The 404 M. I. ADRIAN AND M. DELIBES EEL% FIG. 10 20 30 40 50 60cm 3. Relative importance of each size class of eels eaten by otters on Lucio Bolin and Arroyo Rocina. importance in the diet of very small fish such as Gambusia is noticeable, as their weight is near 1 g and more than 1000 individuals would be needed to satisfy the daily requirements of an adult otter (about l-l5 kg/day; Chanin, 1985; Mason & Macdonald, 1986). Notes on prey choice No attempt was made by us to estimate the available food for otters in the study area. However, some indirect data can help us to understand the prey choice mechanisms of Lutra lutra in Roeina. J. A. Hernando (1978 and pers.comm.) fished in different places of Arroyo Rocina in 1975-76 (using trammel, fyke and other types of nets) and in 1984 (using electro-fishing). We have compared his results (average proportion of each species in all the samplings on each place) with the numbers of occurrences of fish species in spraints of 1979 and 1984 (Table II). Despite the small number of faeces, eels seemed to be captured by otters more often than expected if predation was at random, while the small-sized fish species tended to be consumed less than expected, especially Gambusia in 1984 (as the data for sticklebacks (Gasterosteus aculeatus) and loaches, which apparently disappeared from the area between 1976 and 1984, are difficult to interpret). Carp and blackbass were captured approximately in proportion to their abundance. On the other hand, by comparing the results of commercial fishing with fyke nets in an area close to Rocina in spring 1983 (Molina-Vázquez, 1984) with the number of occurrences of the same items in 43 spraints from Rocina in the same period, we found crayfish and large insects the most common categories in both samples, while eels were more abundant in the spraints. Also, sharp-ribbed salamanders (Pleurodeles waitli) were very common in the captures of the fishermen but did not appear in the faeces. FOOD HABITS OF THE OTTER IN SW SPAIN TABLE 405 II Percentages of different fish species in the total captures with nets (1975-76) and electro-fishing (1984) and in otter spraints at Arroyo Rocina (n = sample size) Fishing 1975-76 Otter diet 1979 n = 54 Eels Gambusias 481 I3l6 251)0 Leaches 5404 Carp Blackbass Stieklebacks 18’75 10’61 423 1346 3125 2000 51)0 01)0 Fishing 1984 142 9513 O00 163 l82 000 Otter diet 1984 n = 43 2F88 7812 01)0 000 01)0 01)0 Discussion The main points emerging from this paper are the following: 1. In Europe, the frequency of occurrence of insects, amphibians and reptiles seems to increase in otter spraints as latitude decreases (see also Macdonald & Mason, 1982; Simoes-Graça & Ferrand de Almeida, 1983; Callejo-Rey, 1984; López-Nieves & Hernando, 1984). The same case has been demonstrated for several species of predators (see Delibes, 1975). 2. The diet of the Doflana otters, especially at Rocina, was quite similar to that of the spottednecked otter (Hydrictis maculicotlis) in Natal, South Africa (Rowe-Rowe, 1977). Both localities have a long and well-marked dry season. 3. Seasonal predation patterns in Doilana were different from the usual in temperate Europe, where crayfish and eels are consumed more often in summer and other fish species in winter (Erlinge, 1967; Jenkins & Harper, 1980; Wise et at., 1981). Not only numbers, but also changes in prey behaviour, brought about in many cases by changes in the environment affecting catchability (e.g. crayfish and eels which bury themselves in mud while other fish species are confined to small pools in Mediterranean summers), are responsible for these patterns of seasonal variation. 4. High numbers of very small fish such as Gambusia (3-4 cm standard length) were eaten. Erlinge (1968) stated that fish under 9 cm were difficult to catch by the otter. However, in our study area, occasionally entire spraints were made up of remains of Gambusia. Also, different authors (e.g. Webb, 1975; Jenkins & Harper, 1980; Wise et at., 1981) frequently found small fish in the faeces of Lutra tiara. This observation could be of relevance to otter conservation because of the little economic importance of small fish. 5. Sharp-ribbed salamanders were not eaten by otter in spite of their abundance, probably because of their skin glands and external, sharp-pointed ribs. Other results (opportunist feeding patterns of the otter in its aquatic habitat, high role of fish and crayfish in the diet, preference for eels, prey size distribution, etc.) were similar in our study area to the known data from other zones (see revisions in Chanin, 1985, and Mason & Macdonald, 1986). We would like to thank L. GarcIa, R. Laffitte and Dr S. Moreno for helping in the collection of spraints. Mr P. López-Nieves, Dr 3. Hernando and Dr A. Callejo provided us with fish bones for comparison and assisted us in prey identification. C. Garcia analysed some of the spraints. E. Collado, Prof. C. F. Mason, 406 M. I. ADRIAN AND M. DELIBES Dr S. M. Macdonald and especially Prof. D. Jenkins kindly revised early versions of the manuscript. N, Bustatnante improved the English. Financial support was obtained from the CSJC-CAICYT (project 944) and through an agreement TCONA-CSIC. REFERENCES Callejo-Rey, A. (1984). Ecologia trdfica de La nutria Lutra lutra (L.) en aguas conEinentales de Galicia y Ia Meseta None, PhD thesis, University of Santiago. Chanin, P. (1985). The natural history of otters. London & Sidney: Croom Helm. Delibes, M. (1975). Some characteristic features of predation in the Iberian Mediterranean Ecosystem. hit. Congr. Game Bid., Lisbon No. 12: 31—36. Erlinge, S. (1967). Food habits of the fish-otter (Lutra luira L.) in south Swedish habitats. Vihrevy 4: 371—443. Erlinge, S. (1968). Food studies on captive otters (Lutra lutra). Qikos 19:259-270. Heruando, LI. A. (1978). Estructura de una comunidaddepeces deJa Marisma del Guadaiquivir. PhD thesis, University of Seville. Jenkins, 0. & Harper, K. 3. (19%O). Ecology of otters in northern Scotland. 2. Analyses of otter (Lutra tiara) and mink (Musrela vison) faeces from Deeside, N. E. Scotland in 1977-78. .1. Anim. EcoL 49: 731-754. López-Nieves, P. & Hernando, J. A. (1984). Food habits of the otter in the Central Sierra Morena (Cbrdoba, Spain). Ada theriol. 29: 383-401. Macdonald, S. M. & Mason, C. F.(1982). Otters in Greece. Oryx 16t 240 244. Mason, C. F. & Macdonald, S. M. (1986). Otters. Ecology and conservation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Molina-Vázquez, F. (1984). La pesca del cangrejo rojo americano y su influencia en el entomb del Parque de Doilana. Rev. En. Andaluces 3: 151—160. Novikoy, 0. A. (1956). Fauna of the US.SJL. Wo. 62. Carnivorous mammals, Jerusalem: LEST Press, 1962. (English translation from Russian.) Rowe-Rowe, D. T. (1977). Food ecology of otters in Natal, South Africa. Oikos 28: 210-219. Simoes-Graça, M. A. & Ferrand de Almeida, F. X. (1983). Contribuçao para o conheciniiento da lontra (Lutra lutra L.) autu sector da bacia do rio Mondego. Cien. BioL EcoL Syst. (Portugal) 5:33-42. Webb, J. B. (1975). Food of the otter (Lutra lutra) on the Somerset levels. I. ZooL, Lond. 177:486-491. Wise, M. H. (1980). The use of fish vertebrae in seats for estimating prey size of otter and mink. J. Zoo!., Lond. 192:2531. Wisefr M. H., Linn, 1. J. & Kennedy, C. K. (1981). A comparison of the feeding biology of Mink Mustela vison and otter Lutra tiara. .1. ZooL, Land. 195: 181—213. Erratum Journal of Zoology Vol. 212 Part 3 July 1987 Adrian, M. I. and Delibes, M. Food habits of the otter(Lutra tiara) in two habitats of the Doñana National Park, SW Spain Amended page 402 (Bufo sp.), were recognized, with marsh frogs (Ranaperezi) most common. No tailed amphibians were found. All reptiles eaten were viperine snakes (Natrix maura). Mallard (Anas platyrhynchos) remains occurred in one spraint. TABLE I Frequency of occurrence of each food category in the sproints of the stud’ area.v Arroyo Rocina 264 sprain Is Lucia Balm n = 334 spraints MAMMALS 0-6 Unidentified mammal 00 0-0 0-3 04 0-4 0-8 0-4 04 7-1 0-0 28-0 18-2 Ranaperezi Discag/csssuspictus Pelobates cultripes Pelodytes puncut!us Hylameridionalis Bufo sp. 3.3 0-9 1-2 0-3 06 0-6 0-4 Unidentified anuran 21-4 11-4 inst-ms - 0-8 0-3 7-1 Natrixmaura Matpo!on monspessulonus AMPHIBIANS 11 0-8 0-0 0-6 Antis plot yrhynchos Gallinuta chloropus Unidentified small bird REPTILES 19 0-0 0-0 06 Orycto!agus cuniculus Microass duodecirneostatus BIRDS n MOLLUSCA Snails Mussels 367 34-8 13-6 7’6 38 56-5 4-5 12-2 0’0 0-0 80-3 803 0-0 32-4 54-5 52-7 3-1 13-2 21-0 Large diving beetles Other and unidentified SPIDERS 62-9 80-1 Procambarus spp. INSECTS 0-8 0-0 00 94-3 Anguilla anguilla Gombusia of mis Cobitispaludicota Cyprinus carpio Micropterus salmoides CRUSTACEANS 5-3 0-4 0-6 3-0 0-4 0-4 0-4 0-0 3-0 0-3 Red-swamp-crayfish occurred in 80-3% of the faeces from Rocina (Table I). Other frequent items were fish (62-9%), insects (54-5%) and amphibians (18-2%). Mammals occurred in 1-9% of the 264 spraints examined. As in Bolin, eels and Qambusia were the most frequently recorded fish, followed by Loaches and carp. Blackbass (Micropterus salmoides) a species not found in Bolin, was recorded in 3-8% of the samples. Most insects were large diving Coleoptera (Cybister sp, Hydrous sp, etc.), presumably captured directly by the otters. Among the amphibians, marsh frog was the dominant species. Rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) remains occurred three times, Mediterranean pine vole (Microtus duodecinwostatus) twice and moorhen (Gallinula chioropus), viperine snake and Montpellier snake (Malpolon inonspessulanus) once each. ,