Narrative Summary Interview with Rabbi Barbara Block by Asja Lazarevic

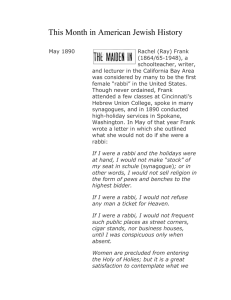

advertisement

Narrative Summary Interview with Rabbi Barbara Block by Asja Lazarevic At the beginning of the interview, Rabbi Barbara Block talks about her religious education and her experiences of growing up as a child of Holocaust survivors. Although her mother was religious, her father was Jewish, but an atheist who sent her to religious school in order for her to know what she is rejecting, and was a bit surprised when Ms. Block in fact did not reject religion. There were times when she had hard time connecting with the established Jewish community, but she never had doubt about being Jewish. Being a child of refugees from the Holocaust, it never crossed her mind to walk away from Judaism. Talking about what is Judaism, she said that for her it is much more than just a religion, it is a civilization, a cultural and ethnic identity. She says that, at that time in the U.S. between 1950s and 70s, expectations of girls and boys were different and gender roles were very much alive. At the age of 10, her parents told her she would not have Bat Mitzvah because it was not important for girls. Although they expected of her to take her education seriously, they were not so worried about her career as they thought that she will get married. In religious life, all Rabbis she knew were men, and it did not occur to her that she could be a Rabbi until she experienced woman leading the services. She enrolled at the Rabbinical school at the age of 50. As that was in 2000s, half of her class were women and there were not any gender based obstacles she experienced on her journey of becoming a Rabbi. She says that growing up feeling very different, she has great empathy for all outsiders, for Blacks, gays and lesbians, for single people. Her religious views very much impact her political views. She thinks that social justice is in the core of Judaism. She argues for public healthcare, and especially for the public education. She is a strong supporter of separation of Missouri State University Semester 20XX Religious Lives of Ozarks Women 2 church and state, and thinks that her passion for justice and emphasis on the community comes from Judaism. Of course, that does not mean that people from other traditions cannot have those values. Being Jewish, she has relatives all over the world who escaped from the Holocaust, but she has a strong American identity. She experienced anti-semitic words during life. Sometimes she had fear of being recognized as a Jew, and links that to being a child of her parents who escaped from Europe. She is informed about anti-semitic incidents in the U.S. and around the world and does not understand how her Christian friends can be totally oblivious to the fact that the myths about Jews are still very much alive and make scapegoats of Jewish people. She had an opportunity to visit Europe and listen to her mother’s stories about Nazis marching into her hometown, and is well aware that Jewish people still need protection as they are in danger. She says that today a lot of people cloak their anti-semitism by pointing at Israel and even dare to ask her “Why are you doing that to Palestinians?” as if she was personally responsible for, the perceived, as she says, actions of Israeli state. She sees that Christians, because they are the most powerful group, easily escape those kind of generalizations and questions. No one asks Christians in the U.S. “Why did you kill all those Muslims in Bosnia?” and no one holds them responsible for the actions of Christians around the world. At the end of the interview, we talked a bit more about Christian privilege, comparing it to the white privilege, and about the danger of collective identities. Missouri State University Fall 2008 Religious Lives of Ozarks Women