Parasitology 5th lecture

advertisement

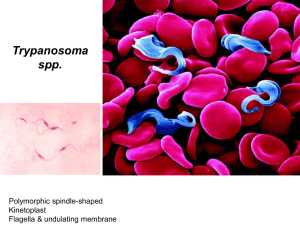

Blood protozoa of major clinical significance include members of genera Trypanosoma (T. brucei and T. cruzi); Leishmania (L. donovani, L. tropica); Plasmodium (P. falciparum, P. ovale, P. malariae and P. vivax); and Toxoplasma gondii. Although the symptoms of African sleeping sickness were documented by Atkins in 1742, the association of the clinical syndrome with its etiological agent, the trypanosome, was not documented until 1902 by Forde. In The Journal of Tropical Medicine, Forde chronicles his treatment of a 42 year-old European male colonialist who presented to his practice in the Gambia Colony in May 1901. The patient complained of fever and malaise, leading Forde to make a preliminary diagnosis of malaria. He initiated anti-malarial quinine treatment, but days later the patient’s conditioned had yet to improve. Slides of the patient’s blood were prepared. This examination ruled-out malaria due to a lack of malarial parasites found in the blood. Only later, Dutton, a second physician from the Liverpool School of identification Tropical of patient’s blood. Medicine, Trypanasoma made brucei in the the Trypanosomiasis or trypanosomosis is the name of several diseases in vertebrates caused by parasitic protozoan trypanosomes. More than 66 million women, men, and children in 36 countries of sub-Saharan Africa suffer from human African trypanosomiasis. The other human form of trypanosomiasis, called Chagas disease, causes 21,000 deaths per year mainly in Latin America. The Tsetse fly Two examples of tsetse fly habitat from West Africa (A) and East Africa (B). The distribution of African trypanosomiasis is completely linked to the range of its vector, the tsetse fly. According to the World Health Organization, countries where the disease is currently epidemic include Angola, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Uganda & Sudan. Countries with high levels endemicity of including Cameroon, Congo, Cote d’Ivoire, Central African Republic, Guinea, Mozambique, Tanzania, & Chad. African sleeping sickness can also be found in low endemic levels in Benin, Burkina-Faso, Gabon, Ghana, Equatorial Guinea, Kenya, Mali, Nigeria, Togo, & Zambia. The disease is a threat to more 60 million people throughout Africa. However, currently only 3 to 4 million of these people are under surveillance, leading to the reporting of only 45,000 cases in 1999. Epidemiologists estimate that between 300,00 and 500,000 cases actually occurred during that same time period. Surveillance is not only essential to track disease trends to determine possible interventions, but also to identify infected individuals so that treatment may be initiated before the disease progresses to less treatable state. Human trypanosomiasis Human African trypanosomiasis. Human American trypanosomiasis There are two clinical forms of African trypanosomiasis: 1. Slowly developing disease caused by Trypanosoma brucei gambiense. 2. A rapidly progressing disease caused by T. brucei rhodesiense. T. b. gambiense and T. b. rhodesiense are similar in appearance: The organism measures 10 - 30 micrometers x 1-3 micrometers. It has a single central nucleus and a single flagellum originating at the kinetoplast and joined to the body by an undulating membrane (Figure). The outer surface of the organism is densely coated with a layer of glycoprotein, the variable surface glycoprotein (VSG). Bite reaction: painful, itchy chancre forms 1-3 weeks after the bite and lasts 1-2 weeks. It leaves no scar. A teenage girl in Uganda with sleeping sickness exhibiting the characteristic chancre on her leg at the site of tsetse fly inoculation (A), and a woman in Uganda with a partially healed chancre just above her elbow (B). Although (C) may look painful, chancres are generally painless with some associated tenderness. Parasitemia: Parasitemia and lymph node invasion is marked by attacks of fever which starts 2-3 weeks after the bite and is accompanied by malaise, lassitude, insomnia, headache and lymphadenopathy and edema. CNS Stage: The late or CNS stage is marked by changes in character and personality. They include lack of avoidance interest of and disinclination acquaintances, to morose work, and melancholic attitude alternating, mental retardation and lethargy, low and tremulous speech, tremors of tongue and limbs, slow and shuffling gait, etc. A history of travel within an endemic region and especially a memory of a bite from a tsetse fly are both key to a clinician’s ability to consider African sleeping sickness when encountering a patient outside an endemic region. If exposure history has been documented, the definitive diagnosis of African trypanosomiasis is made by identifying the protozoa in the patient’s blood, cerebrospinal fluid. A doctor performing a spinal tap to examine the cerebrospinal fluid of a patient suspected to have an infection with African trypanosomiasis To concentrate the trypanosomes in a sample, centrifugation is often advised. An ELISA may also be used to identify antigens, as well as a new serodiagnostic tool termed the Card Agglutination Test for Trypanosomiasis (CATT). Another test called card Indirect Agglutination Test (CIATT) tests for antigens rather than antibodies. It has a high sensitivity and specificity and can distinguish between the two species of trypanosomes. This latter test will allow for rapid and reliable data concerning the incidence of African trypanosomiasis—a key aspect of any prevention and control program. The Card Agglutination Test for Trypanosomiasis (CATT). This inexpensive and rapid serodiagnostic test identifies those patients with antibodies against the organisms, indicating infection Unless treated, African trypanosomiasis is a fatal illness. The most effective treatment intervention for this disease must begin before the organism migrates into the CNS because the most effective drug does not cross the blood-brain barrier. This drug, Suramin, is administered intravenously and most often results in the full recovery of the patient. Melarsoprol is the drug of choice should the disease have progressed sufficiently to affect the central nervous system. This drug is toxic and may lead to myocarditis, renal damage, encephalopathy. Approximately 5% of patients die from this treatment, while another 5% relapse. More recently, Eflornithine, has proven to more safely and efficaciously eliminate the protozoa from the blood stream and has thus been termed “the resurrection drug. The most effective means of prevention is to avoid contact with tsetse flies. Vector eradication is impractical due to the vast area involved. Immunization has not been effective due to antigenic variation. A woman caring for her comatose husband who is dying of African trypanosomiasis, Uganda, 1990