Lumbopelvic Region

advertisement

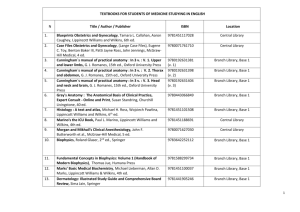

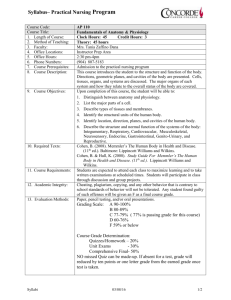

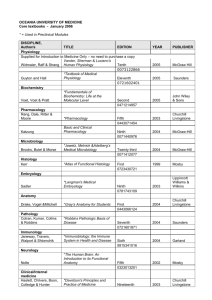

Chapter 18 Therapeutic Exercise for the Lumbopelvic Region Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Anatomy and Kinesiology Basic anatomy L1–L3 similar L4–L5 similar Special features of the zygopophyseal joints Changes do occur with aging Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Osteokinematics/Arthrokinematics All spinal movements involve combined action of several motion segments Flexion: 8–13° per segment Extension: 1–5° per segment Rotation: 1–2° per segment Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Vertebral Movement During Rotation Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Lateral Flexion Coupling varies with sagittal position of segment. Differs among individuals. Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Normal Lumbar Spine Alignment Line of gravity (LOG) – ventral to L4 Any displacement of LOG alters the magnitude and direction of moments on the spine. Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Disc Pressure Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Dynamic Load All body motion increases load on lumbar spine. In a study of normal walking at four speeds, the compressive loads at the L3-L4 motion segment ranged from .2 to 2.5 times body weight. The loads were maximal at toe-off and increased linearly with speed. Capozzo A. Compressive loads in the lumbar vertebral column during normal level walking. J Orthop Res 1984; 1:292-301. Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Factors influencing loads on the spine during lifting: The position of the object relative to the center of motion of the spine. The size, shape, weight, and density of the object. The degree of flexion or rotation of the spine. Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins General rules to lessen the load on the spine during lifting Hold object close to the spine. Reduce the size of the object. Bend at the hips and knees and avoid lumbar flexion/rotation. Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Load transference through the pelvic girdle Passive and active mechanisms. Passive mechanisms contribute to form closure. Active mechanisms contribute to force closure. The SIJ relies on both form and force closure mechanisms for stability. Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Factors Contributing to Form Closure The shape of the joint surface. The friction coefficient of the articular cartilage. The integrity of the ligaments that approximate the joint. Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Pelvic Girdle Sacroiliac joint (SIJ) anatomy is highly variable. The articular cartilage lining the SIJ is unusual. The sacral surface is lined with smooth hyaline cartilage whereas the iliac surface is lined with rough fibrocartilage. This articular combination contributes to form closure at the SIJ. Strong complex ligaments contribute to both form and force closure. Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Osteo/Arthrokinematics Individual variability in joint anatomy and kinematics in early, middle, and late ranges of movement. Movement does occur at the SIJ. The most widely accepted movements are nutation and counternutation. No definitive model exists to define the PICR of the joint. Anterior and posterior iliosacaral rotations occur as do vertical movements with limb loading. Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Nutation and Counternutation Nutation is sacral flexion in which the base of the sacrum moves anterior and inferior and the apex moves posterior and superior. Counternutation is sacral extension in which the base of the sacrum moves posterior and superior and the apex moves anterior and inferior. Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Kinetics Stability is crucial! Pelvic girdle transmits forces from weight of head, trunk, and upper extremities downward and forces from lower extremities upward. The angle of inclination of the articular surface of the sacrum is a significant factor in the stability of the SIJ. Vertical-oriented SIJs subject ligaments to greater stress. Asymmetric loading may occur with LLD. Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Myology Optimal function of force closure mechanisms requires integration of posterior and anterior muscles of the spine and pelvis. Due to multiple attachments, thoracolumbar fascia (TLF) plays a significant role in stabilization. 29 muscles originate or insert into the pelvis. Significant forces can be generated by various combinations and require significant counterforces for stabilization. Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Myology Posterior Latissimus dorsi Erector spinae Multifidus Quadratus lumborum Interspinalis Intertransversarii Anterior External oblique Internal oblique Transversus abdominis Iliospoas Rectus abdominis Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Myology Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Deep ES Vector Forces Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Examination and Evaluation Three critical questions must be answered: 1. Is there a systemic or visceral disease for the source of referred pain into the back or lower extremities? 2. Is there evidence of neurologic compromise that represents a surgical emergency? 3. Are there mechanical findings that guide conservative management? Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Examination and Evaluation Patient history – Critical! Can begin clinical reasoning toward diagnosis. Screening exam – Helps to determine if symptoms from lower quadrant are originating from lumbopelvic region. Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Screening Exam 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. Observation – Posture scan in standing and sitting. AROM – In both standing and sitting. Stress tests – Performed on both lumbar spine and SIJ. Provocation tests – Prone posteroanterior pressure to the lumbar spine. Palpation – Assess tone changes, lesions, pain provocation. Dural mobility tests Neurologic tests – Key muscles, reflexes, dermatomes. Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Tests and Measures 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. Anthropometric characteristics Ergonomics and body mechanics Gait/balance Muscle performance Neurologic testing Pain Posture ROM, muscle length, and joint mobility Work, community, and leisure integration or reintigration Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Think about what tests you would include in each category Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Anthropometric Characteristics May be a risk factor for developing certain types of lumbopelvic syndromes. Example: Male with broad shoulders, narrow pelvis, and high center of mass is more prone to lumbar flexion forces. These characteristics may be difficult to compensate for with a job requiring repeated bending movements. Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Ergonomics and Body Mechanics An assessment of a patient’s job-related duties and physical demands is critical to a positive outcome. Include assessment of: Materials handling Lifting mechanics and capabilities Non-materials handling such as sitting or standing tolerance Workstation ergonomics Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Gait and Balance Gait is a complex functional movement pattern that can indicate pathomechanical factors contributing to lumbopelvic signs or symptoms. Video analysis can be an efficient tool to evaluate the complex interaction of multiple regions on the lumbar spine during walking or running. Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Muscle Performance Force- or torque-generating capability of spinal extensor or abdominal muscles via MMT. Interpret isokinetic testing of trunk muscles with caution. Test muscle performance of deep trunk muscles (i.e., TrA, LM) via specific stability tests using active movements of the extremities. Interpret resisted tests to provoke pain in contractile tissues with caution. MMT of pelvic girdle and pelvic floor muscles can provide pertinent information. Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Neurologic Testing A thorough neurologic examination for the lumbopelvic region consists of 3 parts: Upper motor neuron screening – Upper lumbar central herniation only Neuroconductive testing – Sensory, motor, DTR changes Neurodynamic tests – SLR, PKB, slump maneuver Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Pain Measurement of pain as it relates to disability (i.e., use of pain scales). Examination to determine that lumbopelvic region is the source of pain. Examination to determine cause(s) of pain. Examination to determine physiologic impact of pain. Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Posture Casual observation of standing or sitting posture when patient is unaware. Specific standing, sitting, and recumbent posture. Develop hypothesis regarding relationship of posture to pathomechanical cause of the pain. Develop hypothesis regarding muscle length and its contribution to pathomechanical cause of pain. Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Range of Motion, Muscle Length, and Joint Mobility ROM of lumbar spine, thoracic spine, pelvic–femoral region, and relationship between all regions and the lumbar spine. Muscle extensibility tests across pelvis and hips as well as lumbar spine. Specialized McKenzie testing. Joint mobility including PPIVM, PAIVM, and segmental stability testing of lumbar spine and pelvis. Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Work, Community, and Leisure Integration or Reintegration Measurements of disability such as: Oswestry Low Back Disability Score Million Visual Analogue Scale Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire Waddell Disability Index Clinical Back Pain Questionnaire Low Back Outcome Score (LBOS) Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Therapeutic Exercise for Common Impairments Aerobic capacity impairment Balance and coordination impairment Muscle performance impairment Range of motion, muscle length, and joint mobility impairment Posture and movement impairment Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Aerobic Capacity Impairment Can be considered a secondary condition resulting from incapacitation associated with CLBP. Choose activity that does not increase pain. Benefits of aerobic conditioning include: Enhanced healing Weight loss Favorable psychological effect Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Balance & Coordination Impairment There is proven functional importance of proprioceptive training during rehabilitation of the spine. True stability of the spine at the skill level requires precise and rapid responses to perturbations in the load imposed on the spine. LBP patients have a tendency to fulcrum at hips and low back to maintain balance. Gym balls, wobble boards, slide boards, and foam rolls can be used to train propioception. Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Balance Impairment Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Muscle Performance Impairment Muscle performance impairment can result from any of the following mechanisms: Muscle strain Pain Inflammation Neurologic pathology General deconditioning Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Exercise for Muscle Control Research has established a link between lumbar dysfunction and function of the inner core muscles. Inner core muscles include: Transversus abdominis (TrA) Lumbar multifidus (LM) Pelvic floor muscles (PFM) Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Exercises for Inner Core Control Choose exercises that promote optimal lengthtension properties of the trunk and pelvic girdle muscles. Consider specificity of training (i.e., stability versus torque production). Consider the stage of motor control. Patient-related instruction is critical to successful outcomes. Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Exercise for Muscle Control Inner Core TRA, LM, PFM Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Underlying Premises for Justifying Exercises for Inner Core General strengthening programs for the trunk muscles may not adequately recruit or improve the performance of the inner core. Localized and specific exercise aimed at training neuromuscular control of the inner core may be critical to improving subtle patterns of muscle recruitment necessary for optimal segmental stability of the lumbar spine. Include gluteus medius/maximus, deep hip LRs, latissimus dorsi for optimal pelvic stability. Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Progression Criteria from Core Training 1. Lumbar spine should not deviate from initial starting position (neutral position). 2. Trunk muscles should be functioning at optimal lengths. 3. Rectus abdominis (RA) should not be dominating synergy, and valsalva maneuver is discouraged. Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Supine Inner Core Progression FIRST, SET LUMBOPELVIC CORE! Level I: Single leg slide Level II: Single leg lift until hip is at 90 degrees with floor. Follow with level I, sliding one leg to extended position. Level III: Level II with single leg glide instead of slide. Level III: Bilateral leg lift to 90 degree position, double leg slide. Level IV: Level III but with double leg glide. Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Inner Core Series This is a series of activities designed to recruit the core, aided by superficial muscles as needed, in a variety of positions: Supine inner core series Stomach-lying elbow lift Quadruped arm lift Sitting knee extension Activities of daily living Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Higher levels of stability After neuromuscular control and functional levels of muscle performance are established, additional resistance can be added to progress to higher level functional activities. Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Neurologic Impairment and Pathology Underlying mechanical or biochemical irritation must be treated first. SPECIFIC exercises to improve stability of offending segments/regions can reduce stress on nerve root. Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Muscle Strain Can be the result of: Trauma – Teach patient how to avoid postures and movement patterns that continue to irritate the injured segment(s). Overuse – Improve force/torque production of underused synergistic muscles (timing/balance). Gradual elongation – Support overstretched muscles in shortened range. Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins General Disuse and Deconditioning Commonly develop from general lack of activity. Sit Up 2-Phase Activity: I – Primarily trunk flexion with pelvic tilt (IO and RA) II – Hip flexion phase (EO recruited to neutralize forces on pelvis from hip flexors) Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Sit Up Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Modification for Short Hip Flexors Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Range of Motion, Muscle Length, and Joint Mobility Clinical decisions regarding exercise prescription for ROM, muscle length, and joint mobility must be considered in relation to other regions of the spine, upper quarter, and lower quarter. Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Hypermobility Four factors can be responsible for the development of a hypermobile segment: Trauma Pathology (e.g., rheumatoid arthirtis) Anatomic impairment (e.g., spondylolisthesis) Repetitive movement patterns Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Relative Flexibility or Stiffness Sahrmann term for site of abnormal or excessive movement. In a multijoint system with common movement directions, any given movement follows the segments that provide the least resistance, resulting in abnormal or excessive movment of segments with the least amount of stiffness. With repeated movement over time, the least stiff segments increase in mobility and the more stiff segments decrease in mobility. Sahrmann AS. Diagnosis and Treatment of Movement Impairment Syndromes. St. Louis, Mosby, 2002. Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Hypermobility Improve mobility at sites/segments of relative stiffness. Movement training should be based on protecting the specific direction susceptible to movement (DSM). Sites of relative flexibility should be protected from excessive or repeated movement during exercise and ADLs. It may be necessary to immobilize lengthened muscles in shortened range (e.g., abdominal binder). Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Exercise Example to Treat Relative Flexibility at the Lumbar Spine Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Hypomobility To be most effective, activities or techniques to reduce hypermobility must occur simultaneously with activities or techniques to increase mobility. Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Interventions for Hypomobility Articular joint mobilization Muscle energy techniques Soft tissue mobilization Self mobilization AAROM AROM PNF Passive stretching Active stretching Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Neuromeningeal Hypomobility Loss of mobility of the nervous system can occur as a result of congenital disorders, trauma, surgical complications, or degenerative changes. Two types of neuromeningeal hypomobility: Tethered cord syndrome (contraindication to physical therapy intervention!!) Nerve root and dural movement dysfunction Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Neuromeningeal Mobilization of the Lower Quarter Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Pain The physical therapist is most interested in the mechanical cause of pain as it relates to movement. Instruct patient in postures and movements that reduce or alleviate pain and avoid postures and movements that increase pain. Improve mobility in hypomobile segments and stability in hypermobile segments. This allows painful structures to “rest” and reduce or halt the inflammatory process. Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins McKenzie Approach to Treatment of LBP Use movements that reduce or abolish symptoms. Understand concepts of peripheralization and centralization. Annular fibers must be present to exert force on the NP. Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Sample McKenzie Technique Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Posture and Movement Impairment Educate patient in postures and basic movement patterns that avoid reproducing symptoms. Bed mobility Sit to stand Bending Lifting Stairs Gait Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Proper Bending Pattern Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Common Diagnoses Lumbar disc herniation Spinal stenosis Spondylolysis and Spondylolisthesis Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Lumbar Disc Herniation If the annular tear progresses to full annular disruption, a herniated nucleus pulposus (HNP) results. Clinically, disk herniation can be divided into the following subsets: HNP without neurologic deficit HNP with nerve irritation HNP with nerve root compression Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins LDH Treatment – Acute Medications are often prescribed by referring provider. Controlled rest with posture and activity modification. Avoid flexed and asymmetric postures. Basic movements (core training–heel slides). Soft tissue mobilization and passive stretching may decrease pain associated with spasm. Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins LDH – Subacute and Chronic Treatment should focus on altering postures and movements and associated impairments that produce symptoms. Patient-related instruction is most important intervention to provide patient with decisionmaking tools to protect against developing chronic disability. Self-management exercises are emphasized. Invoke confidence in self management of back pain. Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Spinal Stenosis (SS) Abnormal narrowing of spinal canal (central) or intervertebral (lateral) foramen. Hallmark signs and symptoms: Increased pain upon extension Pain in legs Pain may increase during coughing or sneezing Pain alleviated with flexed postures Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins SS Treatment Improve core muscular performance. Lengthen hip flexors contributing to anterior pelvic tilt. Shorten and strengthen thoracic musculature to correct kyphosis. Use unilateral exercises if asymmetry exists in pelvic girdle and lower extremity (possible scoliosis). Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Spondylolysis and Spondylolisthesis Spondylolysis – Bilateral defect in pars interarticularis. Spondylolisthesis (5 classifications) – Forward subluxation of the body of one vertebrae on the vertebrae below it. Type I – Isthmic Type IV - Elongated Type II – Congenital pedicle Type III – Degenerative Type V - Destructive disease Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Interventions for Spondylolysis/Spondylolisthesis Bracing Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications Avoid extension exercises Avoid exercise, postures, and movements that place shearing forces on the spine Strong emphasis on core strength Exercise, posture, and movement retraining Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Adjunctive Interventions – Bracing Bracing is indicated when exercise alone, used to improve segmental stability and relative flexibility, has failed to produce a desirable functional outcome. External support can provide stiffness to relatively flexible segments, thus providing opportunity for relatively stiff segments to begin to move. May also provide support to overstretched muscles (I.e., external obliques). Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Adjunctive Interventions – Traction Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Summary Thorough understanding of anatomy and biomechanics is crucial!!! Exercises are based on systematic examinations identifying the physiologic and psychological impairments most closely related to the individual’s functional limitations and disability. Exercises should be related to the pathomechanical cause of lumbopelvic conditions. Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Summary (cont.) Exercise management of common patho-anatomic diagnoses must not follow a recipe approach, but rather relate to the patient’s unique impairments, functional limitations, and disability. Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins