Comedy

advertisement

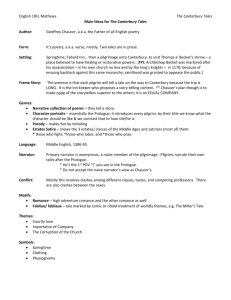

1 Notes on Comedy from Derek Pearsall's article "The Canterbury Tales II: Comedy" The Cambridge Companion to Chaucer There are six tales in the CT that can be said to be primarily comic in structure and theme: FriarT, SumT, MilT, RvT, ShipT, MerT, CookT (the last unfinished) These tales have very clear narrative principles: Time -- Present Place -- Near, usually England Tone -- reductive, almost cynical description "a riche gnof" Worldview -- "There are no values, secular or religious, more important than survival and the satisfaction of appetite" (126). The characters and actions are not satirical and present an amoral world that is not "realistic, no more than the worldview of the romance." II. Fabliaux Four of the six tales are clearly fabliaux: "a tale in which a bourgeoisie husband is duped or tricked into conniving at the free award of his wife's sexual favors." Tales written for upper-class audience in which they laugh at the upwardly mobile and at themselves -- John the riche gnof, and Absolon the courtly lover, clerk. The basic ingredients of the fabliaux are three: husband (a member of the petit-bourgeoisie), a wife (usually younger than the husband), and an intruder (from a different social class, usually a clerk -- which is almost a classless class). 2 "Romance asserts the possibility that men may behave in a noble and self-transcending manner; a fabliau declares the certainty that they will always behave like animals. The one portrays men as superhuman, the other portrays them as subhuman. Neither is "true" or realistic, though we might say that our understanding of what is true gains depth from having different slanting lights thrown upon reality, so that beneficial shock, enrichment, invigoration is given to our perception of the world. Romance and fabliau complement one another, and Chaucer encourages us to look at them thus by setting the Knight's Tale and the Miller's Tale side by side. Each type of story makes a selection of human experience in accord with its own narrative conventions or rules. Out of the interlocking of these and other different types of story, in the general medieval hierarchy of genres, or in the Canterbury Tales as a whole, grows the social relevance of literary form, the fabliaux amongst them" (Derek Pearsall, "The Canterbury Tales II: Comedy," The Cambridge Chaucer Companion, ed. Piero Boitani and Jill Mann [Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1986] 129). "... Some see the fabliaux as the center of Chaucer's artistic creation, finding in them a source for his artistic objectivity that others see rooted in his Christianity and study of Boethius. Similarly, most definitions describe fabliaux as 'realistic' to contrast with an 'idealistic' quality of romance; this implies a judgment that true and faithful representation of humans shows them as coarse and ignoble, self-seeking, and lacking consideration of others. Because Chaucer wrote so many romances, both secular and religious, it seems more appropriate to regard the fabliaux with marginalia in Gothic manuscripts, which not infrequently provide images of action from fabliaux as well as grotesques combining animal and human features. These figures not only accompany romances but also religious texts in manuscripts of great beauty. All indicate a medieval awareness that humans have both body and soul, as a popular poetic form poses in debate, that they live in a temporal world but this is only a shadow of the eternity that is to come. Great energy and vitality are present in what has been called the gothic tension, the balance of these disparate 'realities'" (Velma Bourgeois Richmond, Geoffrey Chaucer [New York: Continuum, 1992] 83). 3 An Anatomy of Interpreting the Fabliaux 1. Definition: genre -- courtly, performative aspect a. Miller, plot, descriptive detail, word play, reference to the medieval drama, senex amans, petit-bourgeois b. Miller and wife, low-class, cradle trick, slapstick fight, dirtier wordplay (pricketh, grint) c. Merchant--corrupt rich Italian, senex amans, fruit tree, Eden joke, key trick (wax, wax) great ironies, blind, false court 2. Political and historical allegories a. Miller--Peasants' Revolt, results of emerging bourgeois in ruling position b. Reeve--emptiness of social pride of lower class, the critique of early factories, the grinding down of humans to beasts c. Merchant--ineffective parliament 3. Religious or doctrinal allegories 4. Humanistic allegories