Leadership Abstract (continued) *Governments are demonstrating an inability or unwillingness to

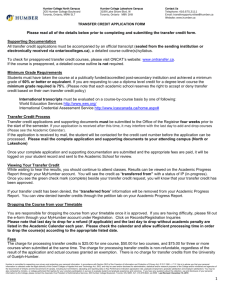

advertisement

Leadership Abstract (continued) *Governments are demonstrating an inability or unwillingness to maintain funding allocations on a par with rising costs, while simultaneously requiring more public accountability by measuring performance indicators. Accessing adequate operating monies presents a serious long-term problem. Unlike some private institutions, becoming financially self-sufficient is not a realistic possibility for any public community college. There is a limit to how far shortfalls in revenue can be made up through increases in tuition, particularly for the typical community college student. College leaders today not only have to spend an inordinate amount of time chasing scarce nongovernmental dollars, but they must also find a recipe for guaranteeing long-term financial health and stability. Colleges are challenged to find solutions to the recent convergence of these critical 21st century issues. This abstract describes how Humber set about, in 1995, to find ways to reinvent itself by (1) evolving into a learning organization, (2) creating new multiple-learningpathway opportunities for its students, and (3) containing costs and seeking new sources of annual funding. The date was not picked randomly. The process of reinvention received a catalytic, not to say inauspicious start when the newly elected provincial government carried through on its pledge to cut operating budgets across the spectrum of the public sector by 15 percent. For Humber, that meant about $13 million, exclusive of any additional monies the college had to spend on early retirement or layoff packages. Nor did these monies ever return to the college on an annual basis, even though enrollments continued to rise in every year following. With a caveat that deficits were not allowed, the government otherwise did not intervene in any college’s efforts to bring its budget into balance. As a result, strategies fluctuated widely as each college proceeded to carry out its own fiscal and programmatic reductions according to its own institutional priorities, values, and modus operandi. DEALING WITH REALITY Fortunately, necessity is also the mother of invention for those willing to seize the initiative. Humber was determined to think creatively to preserve its relevance and health in an exciting but unknown future. A new college strategy was conceptualized, a critical path developed, and tactical implementation plans fine-tuned. However, any action taken had to conform to two inviolable college operating principles: (1) The college could not emasculate itself by cutting services considered essential to successful achievement of long-term goals. An example was the professional development program for staff, long considered the backbone of keeping the college on the cutting edge. (2) There could be no deviation from long-standing college values, namely innovation and risk taking, excellence and quality, customer service, and respect for all people, as well as professional development and continuous learning for staff. Several cost-containment moves appeared obvious and were acted upon immediately. For example, because all staff were aware of the budgetary crisis and the college took great care to avoid layoffs of full-time staff, Humber was able to eliminate programs weak in enrollment, job placement, or quality. Conversely, realizing that if a program was cut entirely it would be very difficult to re-establish, few programs were totally eliminated, although in many cases first-year enrollment was limited temporarily. Also, where appropriate, enrollment cuts were aligned with faculty who chose to leave, thus at once preserving a core of committed faculty and avoiding layoffs of some excellent but junior faculty with low seniority. By providing incentives for faculty and staff who wished to retire, the college was able to hire lessexperienced, cheaper, but more technologically up-to-date replacements who relished the challenge of being part of building a new learning environment. Other doable moves to cut costs, preserve service, and increase revenues were acted upon as follows: *Raising tuition as high as the government, the students, and the market would allow *Outsourcing services hitherto run by the college – namely the bookstore, campus security, food services, and maintenance – thereby eliminating fixed costs while achieving productivity gains and generating new guaranteed revenues *Increasing fee-for-service programs in conjunction with outside professional groups (e.g., firefighters) where students would pay significant surcharges in return for guaranteed employment after graduation *Increasing revenues via contract training with private- and publicsector organizations *Increasing international registrations, at $11,000 tuition per student, up to 5 percent of total full-time enrollment Additional factors helped mitigate a discouraging situation. Unlike the private sector, which faces the reality of the market every day, it appeared unlikely that a public college would be driven out of business entirely. The college realized that it could contemplate a trial-anderror process of adjustment without penalty, other than citizen complaint of reduced service. Humber was able to take advantage of falling prices of educational technology to experiment with new ways to deliver education. Again, because distance education did not respect traditional institutional geographical boundaries, there was potential to increase market share if high-quality programming could be made available online. Because they are quantifiable, cutting costs and increasing revenues tend to be more straightforward than the complex process of managing change. The latter has more potential to upset the established equilibrium, particularly if not carried out humanely, subtly, and incrementally. The most effective way of achieving progress is to demonstrate a flawless transition over time that does not negatively affect the desired mix of managerial style, institutional culture, and staff morale. In fact, it can be argued that the ability to manage the change process smoothly is ultimately more critical to the long-term organizational health of the college than the changes themselves. To give one concrete example, teachers who sincerely believe that they have long provided successful learning experiences for their students resent any suggestion that they must alter their behavior to adapt to the concept of a learning organization. In order to alleviate fears of those who might have felt that the college was attempting to change too dramatically and too quickly, it was critical that the leadership take direct ownership by demonstrating full-time commitment, and by knowing how and when to pull the levers of change. The president in particular had first to provide overall and positive direction, performing much as the orchestra leader who must coordinate all composite parts. Part of that responsibility was to procure acceptance of an integrated strategic plan that would simultaneously create a series of flexible, laddered learning pathways and ensure a sound, ongoing funding base. To smooth that transition, it was important that staff and students understood that there was no intention of throwing the baby out with the bathwater. Although new programming would be introduced, the associate’s degree (postsecondary diploma in Ontario) would remain the core of the college academic offerings. The argument was presented that the college would build on its traditional strengths and continue to respond to new societal demands from its community as always. Above all, in no way would it betray the original mandate and mission. Humber was able to alleviate concern that it was either trying to elevate itself to university status or eliminate faculty and programs in nonacademic (e.g., apprenticeship, English as a second language) areas. Also, while transfer to university had never been part of the college’s mandate, most observers accepted the argument that it was time students gained better access to ongoing educational opportunities. THE NEW VISION Humber realized that it must build learning pathways linked by integrated curriculum in appropriate specialty areas, something not done adequately in the past. This meant that students theoretically and in practice could advance systematically from one level, like apprenticeship, through to associate degrees, to eventually degrees themselves. If at any point students chose to opt for work experience, they would not only be able to re-enter easily, but could also be given appropriate credit through prior learning assessment and recognition (PLAR). The intent was to enable students to continue career and personal enhancement with less duplication, fewer administrative barriers, and increased credit transfer. It was the college’s commitment to use the integrated curriculum framework to facilitate the planning of lifelong learning for each student by clarifying pathway options. This ambitious design was not as naïve or unconnected to reality as first might be thought. There were some important external developments that provided support for new initiatives. First, after many years of Ontario being the only jurisdiction in North America to require 13 years of school – Grade 12 graduates could go to college, hence the lack of transfer programs – the government announced that the 13th year was to be eliminated. This meant that with all high school graduates coming from Grade 12, the playing field for the universities and colleges was suddenly to be leveled. More importantly, in 2003-2004, a double cohort of high school graduates would be seeking admission to postsecondary education. To cope with this influx, and because participation rates from the general population for postsecondary education continued to rise in any case, the government announced a massive capital expansion program. For Humber, this meant two things: (1) It would provide the opportunity to seek new partnerships, particularly with the hitherto intransigent universities; and (2) the enrollment growth allowed experimentation with new programming while minimizing internal fear or opposition that might have arisen from anxious faculty. The college was able to assure the faculty that not only was it unlikely there would be layoffs due to program change, but there would also be opportunity to hire considerable numbers of new staff. Humber realized that it could not easily add new pathways, such as its own degrees, if that meant widespread elimination of existing programs. It was able to position program expansion as a natural extension of planned growth. Even the student government accepted this hypothesis, and with unselfish foresight agreed to a long-term, per-semester, per-capita building enhancement fee worth about $10 million over five years, with the sole caveat being that these funds be used to improve the students’ learning environment. PLAN FOR ACTION Having gained general consensus for the conceptual overview, Humber had to successfully carry out the implementation plan. It was recognized that this would not be an easy task. Many stakeholders in Ontario’s higher education community would not support the direction the college was taking. The universities believed Humber was attempting to encroach on credentials and resources hitherto considered solely in their domain, and some colleges feared they might be left behind, as Humber and a few other colleges gained an inordinate amount of available resources. Private-sector support for better qualified graduates to compete in the worldwide economy helped make Humber’s case, as did the government’s antipathy toward the monopolistic attitudes of the universities. Yet in the final analysis, Humber realized that it must help itself by *not unduly alienating the sensitivities of its internal and external communities; *cultivating and deepening relationships with strategic allies in colleges, universities, and political circles; and *negotiating its way carefully, systematically, and with utmost diplomacy. Following resolute efforts over several years, by 2003, the college could report the following program mix: APPRENTICESHIP. Although always a part of academic programming, in recent years, students’ seats were funded by federal and provincial governments on a competitive basis; in 2002-2003, over 2,000 students were registered at Humber in various fields. ASSOCIATE DEGREES (i.e., two and three year diplomas). Humber grew from 11, 500 full-time per-semester students in 2000-2001, to 14,000+ in September 2003, all with college-level funding. POST-DIPLOMA PROGRAMS. These are one-year, accelerated curricula for university graduates only, in 38 fields, enrolling about 1,400 students annually, all at college-level funding with tuition surcharge. TRANSFER TO UNIVERSITY. Numbers increased dramatically from the past as universities, many outside Ontario, began to respond to changing times and accept more Humber students with advanced standing. NURSING. The government mandated all nurses to hold a baccalaureate degree for entry to practice by 2005; 75 percent of the province’s nursing students were enrolled in colleges. University-level funding was provided by the government to encourage and assist colleges to build collaborative partnerships with degree-granting institutions. Not surprisingly, the universities made this difficult in terms of funding, curriculum, and control. Humber prevailed upon the Minister of Training, Colleges and Universities, to approve the only special consent given in eight years for a partnership outside Ontario, whereby all four years of the degree would be offered by Humber, at Humber, under the supervision of the degree granting of the host University of New Brunswick. Humber presently has the largest program in the province, with 240 first-year student intake, all at university level funding, which is double that for colleges. APPLIED DEGREES. Working with several colleges, Humber prevailed upon the Minister, against wishes of the universities, to allow colleges to grant degrees in applied fields. Tactically, the decision hinged on making the case that economic need could be demonstrated, private sector support was forthcoming, and universities were not presently offering such programming, e.g., paralegal. A competitive pilot-program project allowed a maximum of four degrees per college, processed through the arms-length Quality Assessment Board, for a system total of 24, later hiked to 34. A small government funding increase was supplemented by charging university-level tuition. INSTITUTES OF TECHNOLGY AND ADVANCED LEARNING. Three colleges made the case that the pilot project maximum was insufficient to create a critical mass of degrees which would make substantial impact; they also agreed that a legislated name change was necessary in order to compete successfully with universities, for students and for job placement with industry. In February 2003, Humber was given approval to offer up to 15 percent of its programming – i.e., 25 out of 160 – in degrees, with no cap on enrollment, and its name was legally changed. UNIVERSITY OF GUELPH-HUMBER. Capitalizing on the upcoming elimination of grade 13 and the concomitant enrollment explosion in postsecondary education, Humber sought and established a partnership with the University of Guelph. The university is situated less than one hour’s driving time from Humber’s main campus, and is consistently ranked at or near the top of comprehensive universities in Canada. After due diligence, the partners chose each other carefully. Humber’s aspirations were access to more degrees for its students, as well as funding improvement. Guelph was restricted in growth at its own main campus and desired a foothold in the large Toronto market. The real intent of the partnership, however, was to create a new postsecondary option that blended the practical strength of the college curriculum with the theoretical muscle of the university; the partnership went beyond an articulated transfer agreement. Programs were designed in seven areas, will enroll almost 3,000 full-time students by 2006, and will enable students to earn both a college diploma in one field, e.g., wireless technology, and a Guelph honors degree in another, e.g., Bachelor of Science – all in four years, at one location: Humber. Through extraordinary cooperation and mutual respect on the part of staff at the two institutions, curriculum was totally reworked and integrated, joint faculty appointed, admissions coordinated, and costs cut for students because they would be expected to commute. A capital grant of $28.6 million was received from the government, while the institutions put up another $14 million. An impressive building will open in September 2003. Most important, even though Guelph’s research and graduate school activities would not be a priority for Humber’s 50 percent share of courses and staffing, funding and tuition were secured at university level for all four years. RANDOM THOUGHTS IN RETROSPECT The developments of the last few years have been challenging and exhilarating. Clearly, focused perseverance in taking advantage of emerging opportunities can simultaneously neutralize difficulties, broaden student options, and stabilize institutional finances. However, bold visionary thinking is only as effective as an institution’s ability to deliver implementation effectively. In that connection, it might be useful to enunciate several insights that proved crucial in facilitating Humber’s overall change strategies: *There is no magic formula or cookie-cutter approach to fit all; vision and strategy must differ from college to college, region to region. *Implementation plans need to remain elastic, with regular realistic assessments to decide midcourse redirection if necessary. *No action can be a one-off, and any action must be integrated within the overall activities of the college. *Tactics and activities must be designed to gain buy-in and to advance the process, which must be deep, wide, and constantly reinforced. *The importance of collaboration, consensus building, and taking personal responsibility through ownership can never be minimized; there can be no success without involvement, empowerment, and approval of stakeholders. *Use professional development experts, especially from faculty, to mentor late bloomers – in the exciting potential of educational technology, for example – and to make the process positive. *Measure outcomes regarding progress regularly, preferably through a campus-based office of institutional research. *Publicize successes and best practices – e.g., responses to how your actions improved learning – and constantly foster an organizational climate that promotes learning. *Set up structures that reflect the learning organization, such as vice president of learning services; imbed learning into college values. *Be careful of overemphasis on one-time, quick-hit revenue generation, or on the wonders of costly innovative technology. *Make sure information technology is used as a creative tool, and that systems serve the needs of the learning organization and not just the administration. *Curtail the role of those who oppose the agenda; take care in selecting positive people with institutional influence for strategic steering committees. *Be cautious of excessive rhetoric regarding vision and accomplishments; let results speak for themselves. Contemporary college leaders should take satisfaction in knowing that their efforts are making a difference in ensuring a solid future for their colleges as 21st century learning organizations. But they should also intuitively understand that development of a healthy learning organization can only be viewed as an ongoing journey – never as a destination. In that sense, they should also take comfort in knowing that their successors will build on the foundation laid today, as this generation embraces new ideas and implements new solutions in dealing with the organizational and learning challenges that inevitably lie ahead. Robert A. (Squee) Gordon mailto:robert.gordon@humber.ca is President of Humber Institute of Technology and Advanced Learning. ___________________________________________________________

![Building Better Opportunities Networking[...] - CERT Ltd](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/009964886_1-3ba46e4bbce7845f0ad29798ce4c871c-300x300.png)