Bauhüs V S0118621 bachelorthese

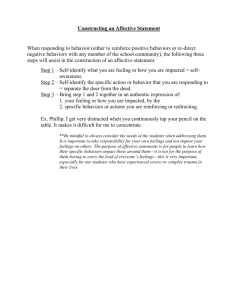

advertisement