Randy Stolle - Capstone Essay - CIL

advertisement

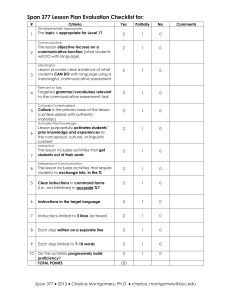

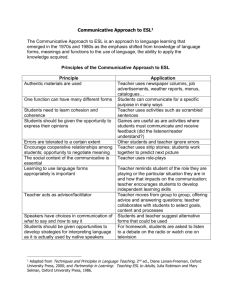

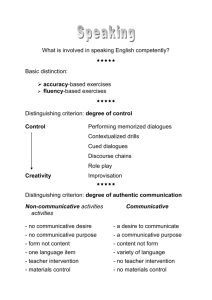

The communicative approach to language learning – Meeting stakeholder expectations Randy Stolle Vanderbilt University Department of Teaching and Learning Curriculum and Instruction Leadership Education 15 September 2008 Stolle 2 Abstract An increasingly global economy and multicultural society are affecting our everyday lives, and it is important that we adapt to the changes that accompany such growth. One of the most prevalent and public challenges we deal with is the language, or perhaps languages, with which we conduct our day-to-day affairs. This paper discusses the current status of foreign language teaching in the United States and the need to improve what the education system is currently offering. The author of this paper compares the Grammar-Translation Method to the Communicative Method, arguing that the latter of the two better meets student expectations and national standards created under the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001. Both curricular approaches are explained in detail, bringing to light the advantages and disadvantages of each. The Communicative Method does not exclude learning grammar. In fact, a communicative classroom may follow a grammatical syllabus. The advantage is the added focus on finding meaning and use in the language. The author addresses how national standards are met and how students can be effectively assessed according to the Communicative Method. Student attitude and motivation are discussed in terms of being a positive influence in a communicative setting, yet a negative influence in the Grammar-Translation classroom. The author provides suggestions on how instructional methods and materials can change to provide a better communicative learning experience both in and out of the classroom. Textbooks, computer technology and communicative activities are each discussed. The author also makes a point of addressing how the learning environment extends beyond the classroom and beyond secondary education. At the same time, opportunities available in schools should be offered in earlier years. The paper is clear in its purpose: successful foreign language classrooms put an emphasis on communication in the target language. Stolle 3 Every year in the United States we send millions of children to school to receive an education that will prepare them for a successful future. Highly-qualified teachers create lessons from rigorous curricula which have been developed to meet the needs of the individual and the global society. On a daily basis, students attend classes and are presented with concepts and information related to mathematics, science, history, technology, art, language and other subjects which are constantly developing and included in school curriculum. All of this is done with the expectation that we are providing the best education possible to prepare the future leaders of our world. The No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 (NCLB) calls for “accountability for results, more choices for parents, greater local control and flexibility, and an emphasis on doing what works based on scientific research” (U.S. Department of Education, n.d.). National standards have been created to ensure that our students are academically competitive both nationally and internationally. Since foreign language has been identified by NCLB as a core subject area it is important to look at the approaches educators are taking to meet the prescribed benchmarks. In the field of foreign language education there are two main approaches to teaching and acquiring language. The first is the Grammar-Translation Method, which is based on the theory that language learning and proficiency stem from knowledge of grammar. The second is the Communicative Method, which “understands language to be inseparable from individual identity and social behavior” (Savignon, 2002, p. 210). Although both of these approaches are referred to as ‘methods’, it is important to note that there is not a specific activity from which each approach spawns. There are, however, activities that lend themselves more to one approach than the other. Stolle 4 Since there are teachers, schools, and education systems which claim to use the Communicative Method when, in fact, they are using the Grammar-Translation Method, it is important for this paper that a common definition of communication be established. Dictionary.com, which provides definitions from the Random House Unabridged Dictionary, defines communication as “the imparting or interchange of thoughts, opinions, or information by speech, writing, or signs” (Dictionary.com, 2008). As students learn to speak, listen, read and write in a foreign language it is important that we also include observation as an essential component of communication, for much of what we communicate is non-verbal in nature. Despite resistance in the political arena, the era of English-only in social and business situations is nearing its end for the majority of the population of the United States. Foreign language education must meet the needs of an increasingly globalized society by preparing the youth of this nation to communicate effectively with those of other languages and cultures. The challenge we face in the classroom is teaching students how to use a language and not just teach them about a language (Brown, 1987). The Communicative Method addresses these issues, meets national foreign language standards, increases student motivation and stretches learning beyond the boundaries of the classroom. What is the Communicative Method? The Communicative Method embraces the idea that linguistic proficiency is the ability to communicate a message in the target language in real-life situations (Johnson, 1996; Ruiz-Funes, 2002). A key point of communicative teaching and learning is that students interact instead of merely reacting to a stimulus (Littlewood, 1981). Certainly this approach to language learning focuses more on oral interaction than other approaches, but it is not exclusively concerned with Stolle 5 face-to-face communication. Reading, writing, listening and observation are also emphasized components of communicative. What separates the Communicative Method from other traditional methods is that language itself is not seen as the sole subject matter. “Language considered as communication no longer appears as a separate subject but as an aspect of other subjects” (Allen & Widdowson, 1979, p.125). It is considered a device for communication and a tool used to study various other subjects. For example, a French class reading Les Miserable will be more concerned with themes found in the story than the grammar used in each sentence of the story. The ability to organize one’s thoughts, explain and justify personal beliefs and appropriately participate in conversation conducted in the target language are common objectives of a communicative curriculum (Harley, Allen, Cummins, & Swain, 1990; Ruiz-Funes). Much like the Grammar-Translation Method, the Communicative Method teaches correct sentence structure. The Communicative Method, however, boasts the addition of being able to use correct sentence structure in context with the various forms and topics of conversation. Foreign language is taught in a manner that makes it accessible to everyone and useful outside of academia. Savignon found in her research of communicative language teaching and learning that students who practiced communication instead of pattern drills performed with equal accuracy on assessments of grammatical structure and that their communicative competence markedly surpassed those who did not study contextualized language (Savignon). In other words, the whole-task practice provided by the communicative approach is more efficient than the discretepoint practice focused on by the Grammar-Translation Method. Stolle 6 The Communicative Method also meets national standards as set forth by NCLB. Standards, much like the communicative approach, focus on what students are able to do with the language. Each objective is met by the student’s ability to speak, listen, observe, read or write in the target language. A student’s overall communicative proficiency is a measurement of how well he or she has mastered the standards. Language learners in a communicative environment will find that the activities they participate in improve motivation (Littlewood). This, as well as foreign language standards, will be discussed more in depth later in this paper, but suffice it to say that communicative language learning gives deeper, connected meaning to words and phrases because they are contextualized. Vocabulary and points of grammar are used not because a pattern drill requires it, but because they are actually needed by the student. As with any approach to teaching and learning, a communicative approach to language acquisition poses certain difficulties. Perhaps the greatest obstacle is the lack of teacher familiarity with and understanding of communicative language teaching. Most current foreign language teachers were probably enrolled in both secondary and higher education classes that subscribed to the Grammar-Translation Method. To successfully make a change to a communicative approach, schools may need to invest time and money in professional development for their teachers. Another potential difficulty with the communicative approach is finding authentic situations for communication in the target language, especially in areas of the United States that are not linguistically diverse. Real-life communication is vital to the success of communicative language learning and must be made available to students. This dilemma can be addressed on a Stolle 7 daily basis by teachers using the target language as a means of instruction (Ruiz-Funes). Modern technology can also provide students with daily opportunities to use the target language via the Internet and its many applications. Students may have a difficult time with communicative language teaching because it often offers independent, paired or group practice as opposed to teacher-led instruction. In these situations the students will not always be directly supervised, which may cause problems if students are thrown into this type of situation too fast. They need sufficient practice and a shared vision of the learning goals and objectives before they can be turned loose. Teachers must slowly wean students from their dependence on the teacher (Littlewood). What is the Grammar-Translation Method? The Grammar-Translation Method, also referred to as the Traditional or Classical Method, is an approach to teaching foreign language which has been used to teach students to read and write language for a thousand years (Kercel, Brown-VanHoozer, & VanHoozer, 2002). The driving theory behind the Grammar-Translation Method is that learning a new language is effectively done through study of the grammatical structure of the language. The expectation is that once students have learned the proper structure of a language they can use it to communicate. To attain the goal of language learning, the method employs activities such as memorizing vocabulary lists, conjugating lists of verbs and translating text from one’s native language to the target language, or vice versa. There are some obvious advantages to a grammatical approach to language learning. First, in the United States foreign language education is traditionally a part of secondary education. This means that by the time a student is able to study a foreign language, he or she has received Stolle 8 almost a decade of instruction about English grammar. In many instances students may transfer their base of English grammar to the study of another language. A second advantage to language acquisition through grammar is that many resources exist which adhere to this approach. Most foreign language textbooks follow a grammatical syllabus which can easily be applied to the classroom. Also, when textbooks are purchased they come with activities, ideas for lessons and some include chapter tests which can be used by the teacher to easily assess student comprehension. Thus, the Grammar-Translation Method requires relatively low skill on the part of the teacher (Brown). In an era of teacher shortages and paraprofessionals who have not been trained in pedagogy, this may be beneficial. We live and work in a time of educational standardization. Students must reach benchmarks which show they are prepared to move on to the next level of learning or application. The ease with which this approach can be standardized is advantageous in that lessons and tests are generally simple to create and score. By standardizing language, however, we may find ourselves limiting linguistic production and suffocating creativity. Just as there are advantages to the Grammar-Translation Method, there are equal, if not greater, disadvantages. First and foremost is that it does virtually nothing to enhance a student’s communicative ability in the language. Students are asked to drill grammar until it is learned and then use it in communication. There is little to no context during the skill-building phase because language and language use are kept separate (Brown; Ruiz-Funes). Just as we do not expect that students in a graphic arts course will become skilled artists by simply learning about the various mediums and tools of design, we should not expect our language learners to become conversationally competent individuals by learning about language structure. Mastery of Stolle 9 selected content vocabulary and grammar is useless unless accompanied by some meaningful situation or context. In our effort to streamline the learning of a foreign language by basing it on our knowledge of our own language we may create an overdependence on comparing the target language to English. Students who slip into the error of thinking that languages may be successfully translated word for word will commonly ask their teachers, “Why is it like that in Spanish? We don’t do that in English.” The resultant discussion is a potentially lengthy comparison of two languages that does little to advance one’s ability to use the target language. The current President of the American Council on the teaching of Foreign Languages wrote on the organization’s website that “accurate translation requires not just translating “words” but the ideas behind those words—and this requires capturing the context in which the words are being used” (Clifford, 2008). If we focus too heavily on the grammar then we may miss the nuances of the language. We surrender creativity to sentence structure, forgetting that our first language is filled with colorful expressions which render deep meaning in context even though they may not always make grammatical sense. Idioms, for example, are expressions which often do not translate well because they are often of a cultural nature. The cultural origin is what gives life to the words and phrases. NCLB asks that we teach these cultural terms in an effort to create understanding of other cultures and to form a deeper connection with the target language. Meeting the Standards “Language and communication are at the heart of the human experience. The United States must educate students who are linguistically and culturally equipped to communicate successfully in a pluralistic American society and abroad” (American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Stolle 10 Languages, n.d.). The American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (ACTFL) created standards and objectives which have been adopted nationally under NCLB. Their goal, as Leonard Newmark explained, is not to get students to say something or understand something, but “to say something with understanding” (1979, p.162). In order to meet this goal, standards and objectives have been divided into five categories: Communication, Cultures, Connections, Comparisons and Communities. Phrases such as “engage in conversations”, “exchange opinions”, and “use the language” define what students should be able to do with the language. These behavioral objectives demonstrate that learning a foreign language is not an end in and of itself, but is a means to an end. This means-to-an-end approach can be carried out best by communicative teaching and learning since the point of the communicative approach is to use language in real-world context. In fact, only one national standard could be argued to lend itself more to the Grammar-Translation Method than the Communicative Method. Standard 4.1 states: “Students demonstrate understanding of the nature of language through comparisons of the language studied and their own” ( ACTFL). Assessing student progress towards the goal of mastery of the prescribed standards is often put in terms of proficiency. Proficiency concerns itself with both qualitative than quantitative ability and growth. A communicative assessment does not test the ability to restate a rule, but to apply a rule in various contexts. It is not the memorization of vocabulary, but the use of vocabulary that qualifies one as being proficient. Testing the ability to manipulate language according to one’s situation and role within that situation is a communicative assessment that tests higher order thinking. The assessments that test this type of production are often difficult to execute with a large number of students, but if Stolle 11 our goal is communication then we cannot settle for a paper-and-pen multiple-choice test that does not check one’s ability to produce anything. Oral proficiency interviews are beneficial because they find the performance comfort level of the students and the ceiling at which individuals can perform. Student progress can also be tracked as they are classified after each interview as either novice (low, mid or high), intermediate (low, mid or high), advanced (low, mid or high) or superior (ACTFL). Educators should not test one aspect of communication only. A true assessment of communicative ability should include sections on speaking and listening, reading and writing. These tests may not be able to be administered at the same time, so teachers should stagger what they assess throughout the school year. Effective use of backwards design, as presented by Wiggins and McTighe in Understanding by Design, will align summative assessments with national standards. Formative assessments will give the teacher insight into how to pace the class and what aspects of the language and language production to focus on before any summative testing is done. Attitude and Motivation As a new Spanish teacher this year, I asked my students on the first day of school to answer two questions. The first was, “Why are you taking this class?” As a whole, my students were very open and honest in their responses. The majority of the students admitted that they enrolled in my class to satisfy a school or parental requirement. The difference in attitude between a student being forced into taking language course and a student with a personal desire to learn the language is paramount when it comes to the scope and sequence of the course and daily lesson planning. Those forced into a course are less likely to take risks in using the language. Students Stolle 12 who are not willingly taking a course are not likely to take risks, which often leads to early fossilization (Brown, Littlewood). Since communicative teaching and learning relies heavily on relationships within the learning environment, teachers should take time to build the trust of the class and promote a risk-taking atmosphere before delving deep into communicative activities. The second question I asked my students was, “What do you expect to be able to do with Spanish at the end of this year?” The overwhelming majority of my students replied that they wanted to use Spanish to speak with friends and family members. Nobody claimed a desire to master Spanish grammar. Since most current foreign language curriculum designs focus more on reading and writing in the target language than listening and speaking, and since “the grammatical syllabus reduces motivation for those seeking practical use”, I had to make adjustments to meet the expectations of my students (Wilkins, 1979, p. 82). Referring to the Grammar-Translation Method, Osborn states that “perhaps the most damning indictment in this era of the “student as customer” is that it is not fun” (Osborn, 2002). Can we honestly expect students to enjoy themselves when they are enrolled in a class that does not meet their expectations? They can see my effort at making class meaningful and they are responding with honest, concerted effort. In research done by Sandra J. Savignon, students were clear in stating their preference of meaningful learning as opposed to an approach of learning formal features of a target language. Her work and the work of other professional educators have shown that motivation is a key factor for learning. Students in any field of study are shown to have an increase in motivation when they are presented with information that addresses a personal need. Learning something that is personally meaningful in a way that is meaningful encourages students to take intellectual ownership of the content (Reagan, 2002; Brown; Ruiz-Funes). Stolle 13 Littlewood writes, “The development of communicative skills can only take place if learners have motivation and opportunity to express their own identity and to relate with the people around them.” The key here is that motivation must be met by opportunity. Much of this opportunity will be made available through a rethinking of the learning environment. Changing Instructional Methods Classrooms which follow the Grammar-Translation Method make use of traditional materials and instructional methods that are common in most classrooms regardless of the subject. Perhaps the most common and influential instructional tool throughout the entire education system is the textbook. Schools spend thousands of dollars on content-specific books which have been developed to enhance the reader’s ability to master key concepts pertaining to the subject. Foreign language textbooks are generally created following a grammatical syllabus. These books generally contain a plethora of writing drills and are often accompanied by audio compact discs which allow students to hear native speakers. Neither of these practices, however, allows students to interact with other speakers of the language. Motivation will suffer if the foreign language classroom becomes “the locus of excessive rote activity – rote drills, pattern practice without context, reciting rules, and other activities that are not in the context of meaningful communication” (Brown, p.49). It is not my intention to devalue current textbooks; rather I hope to persuade educators to make better use of them as an aid to learning. Teachers must employ methods and procedures that address the standards they claim to be meeting. To meet the objective of communicative proficiency teachers must consider the situations in which language learners may find themselves that require use of the language. Once the potential opportunities for language use have been identified, students should Stolle 14 participate in and practice activities that require the same skills. A situational syllabus may be combined with a grammatical syllabus by identifying common occasions when specific points of grammar would be used. Principals of backwards design will strengthen this type of syllabus just as it will strengthen the aforementioned assessments. Whereas in years past it was considerably more difficult to connect foreign language learners with native speakers of the language they are studying, great advances in technology make it possible for students in the modern classroom to connect in real-time with native speakers all over the world. The Internet has opened doors to global communication for educational purposes via e-mail, Instant Messaging, blogging, web pages, video conferencing, shared white boards, and Internet radio. A high school classroom in Tennessee could enter a chat room to discuss current events or literature studied in their Spanish class with students from another class in Argentina who have been studying the same topics. Communicative competency will increase as students are able to apply what they have learned to real-life situations. Language learners should be prepared to listen and understand natural speech, which may include false starts, hesitations and other everyday occurrences. They should also prepare to hear various tempos, clarity of articulation and regional accents. The rate of transfer is sure to increase as students prepare under similar circumstances of authentic speech. Just as students should use the target language as often as possible when studying, teachers should use the target language as often as possible in their teaching. Speaking the foreign language should not be done in addition to teaching, but rather as a means of teaching. Modeling instructions while explaining them in the target language will help students figure out what they need to know, and they will improve their observation skills. Students will struggle initially, but Stolle 15 this is part of the learning process. All too often teachers will communicate with their class in the target language for everything except the explanation of an assignment. Students are inadvertently given the message that the target language is good to use unless the communication is of some importance (Littlewood). The ability to follow directions in the foreign language is a perfectly acceptable assessment tool, and the necessity to communicate will motivate students beyond any early inhibitions concerning language use. Also, if a teacher must explain in English the directions for a foreign language assignment it is likely that either our students will not be able to complete the assignment well in the target language or the assignment does not effectively assess their ability to use the language. Extending the learning environment beyond the classroom After graduating from high school, students will begin interacting with the world on a larger scale. Many continue their studies through enrollment in higher education. Others seek immediately to apply their education and join the work force. Some will enlist in a branch of the military and serve their country. Regardless of one’s future plans, the ability to communicate in a foreign language will be at least beneficial if not essential. I propose that language learners begin early using foreign languages in situations that exist outside of the classroom. After all, fluency or proficiency is rarely achieved by classroom study alone (Brown; Littlewood). A communicative based curriculum may offer the chance to discuss matters of relevance that exist beyond the classroom. It might provide opportunities for students to lend service to nearby target language communities. A communicative approach may even give students the time and the chance to simply socialize with friends in the target language without the fear of grades looming. Defining and preparing students for situations, roles and topics that they are likely to Stolle 16 deal with throughout their lives will have a greater impact on language acquisition and future use than the number of authentic texts we ask our students to read. Conclusion Within the realm of foreign language education, communicative efficiency must hold a higher priority than grammatical perfection. Just as learning to drive a car requires several distinct functions to be performed as one complete task, learning a language requires that distinct aspects of a language meld and work simultaneously. In no other way will our education system produce competent individuals who can use a second language to benefit themselves and others. As we continue to refine our education system, preparing ourselves intellectually to face any challenges we may face as individuals or as a nation, let us not look at language acquisition as an end goal but rather a means to an end. Yesterday’s Grammar-Translation Method has served its purpose, but as the world changes so must our approach to teaching language. Our economy will continue to expand outside the boundaries of our nation and our society will continue to diversify from within both culturally and linguistically. The strength of our relationships with each other relies on our ability understand one another via clear, open communication. Communication is the essence of foreign language education in the United States. The Communicative Method is an approach that makes language learning applicable to all learners and it meets the standards to which educators are held accountable. In order to bring the Communicative Method to its fullest potential in the classroom there must be an increase in research on various aspects of this approach: instructional methodology, instructional materials and assessment. Professional development courses must also be designed Stolle 17 that can prepare teachers to move towards a more communicative classroom atmosphere. Educators must network and share their success. The need for speakers of a foreign language will only increase, so we as educators must meet the demand. Stolle 18 Works Cited Allen, J. P., & Widdowson, H. G. (1979). Teaching the communicaive use of English. In C. J. Brumfit, & K. Johnson (Eds.), The Communicative approach to language teaching (p. 125). London, England: Oxford University Press. American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages. (n.d.). National standards for foreign language education. Retrieved February 3, 2008, from American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages: http://www.actfl.org/i4a/pages/index.cfm?pageid=3392 American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages. (n.d.). Testing for proficiency. Retrieved August 10, 2008, from American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages Web site: http://www.actfl.org/i4a/pages/index.cfm?pageid=3348 Brown, H. D. (1987). Principals of language learning and teaching. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall, Inc. Clifford, R. (2008). About ACTFL: Message from the President. Retrieved September 13, 2008, from American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages Web site: http://www.actfl.org/i4a/pages/index.cfm?pageid=4013 Communication. (n.d.). Dictionary.com Unabridged (v 1.1). Retrieved August 16, 2008, from Dictionary.com website: http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/communication Harley, B., Allen, P., Cummins, J., & Swain, M. (Eds.). (1990). The development of second language proficiency. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. Johnson, K. (1996). Language teaching andsSkill learning. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers Ltd. Stolle 19 Kercel, S. W., Brown-VanHoozer, S. A., & VanHoozer, W. R. (2002). The Entangled future of foreign language learning. In T. A. Osborn (Ed.), The Future of foreign language education in the United States (p. 39). Westport, Connecticut: Bergin & Garvey. Littlewood, W. (1981). Communicative language teaching - An introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Newmark, L. (1979). How Not to Interfere with Language Learning. In C. J. Brumfit, & K. Johnson (Eds.), The Communicative approach to language teaching (p. 162). London, England: Oxford University Press. Osborn, T. A. (Ed.). (2002). The Future of foreign language education in the United States. Westport: Bergin & Garvey. Reagan, T. (2002). "Knowing" and "learning" a foreign language: Epistemological reflections on classroom practice. In The Future of foreign language education in the United States (pp. 45-61). Westport, Connecticut: Bergin & Garvey. Ruiz-Funes, M. T. (2002). On teaching foreign languages - Linking theory to practice. Westport: Bergin & Garvey. Savignon, S. J. (2002). Interpreting communicative language teaching. New Haven: Yale University Press. U.S. Department of Education. (n.d.). Frequently asked questions: Answer - NCLB. Retrieved May 21, 2008, from U.S. Department of Education Web site: http://answers.ed.gov/cgibin/education.cfg/php/enduser/std_adp.php?p_faqid=4 Stolle 20 Wilkins, D. A. (1979). Grammatical, situational and notional syllabuses. In C. J. Brumfit, & K. Johnson (Eds.), The Communicative approach to language teaching (p. 82). London, England: Oxford University Press.