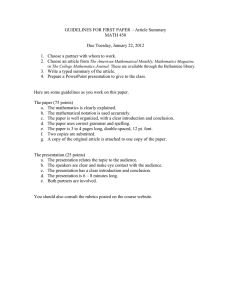

Integrating Children's Literature into the Elementary Math Classroom

advertisement

Children’s Literature and Math Running Head: CHILDREN’S LITERATURE AND MATH Integrating Children’s Literature into the Elementary Mathematics Classroom Lauren Blood Capstone Essay Peabody College, Vanderbilt University Spring 2009 1 Children’s Literature and Math 2 Abstract The integration of subjects is becoming increasingly more popular with educators, and yet rarely is the idea of linking mathematics and literacy considered. This essay delineates the benefits of integrating children’s literature into the elementary mathematics classroom. The National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (1989) asserts children need to be active constructors of mathematical knowledge, and children’s literature presents both problems and methods of solving them in an authentic manner while portraying mathematics in a unique context. Through teachers utilizing children’s literature, students build math-to-self connections, freely explore concepts, and gain positive attitudes towards the subject. A new set of mathematical discourse is readily available to students, creating a community of learners. A wide variety of methods to group students and arrange the classroom are also made possible through the integration of math and literature. With regards to choosing the actual literature to use in the curriculum, firm guidelines exist to ensure quality literature is chosen that invites readers while demonstrating accurate mathematics. Teachers should also consider the various forms of literacy on the Internet to maximize their instructional possibilities. The use of children’s literature in mathematics has been found to deepen mathematical understanding and increase student achievement as material is integrated across the curriculum. An array of extension activities and assessment measures are also made possible through the connections between the two subjects. Finally, this essay demarcates the process a teacher should take when first considering the use of children’s literature in the elementary mathematics classroom. Children’s Literature and Math 3 Introduction Integrating the curriculum is a popular area of discussion among educators. McDonald and Czerniak (1994) denote that learning gains occur when ideas are viewed across content areas because relationships become clearer to the students. Where some may think that there is no use of mathematics outside the classroom, just the opposite is true; mathematics is used in science, the social sciences, medicine and commerce (Ronau & Karp, 2001). Because math is widely prominent in the world, it is crucial for a teacher to demonstrate its presence to his or her students. Whiten and Wilde (1992) assert that children’s literature motivates students to learn, celebrates math as a true language, provides students with an authentic context for conceptualizing math, fosters number sense, and provides a clear mode of integration into the other major subject areas. With this many benefits as products from using children’s literature in the math classroom, it would be a loss to not utilize this rich set of resources. The National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (1989) avows the following: Many children’s books present interesting problems and illustrate how other children solve them. Through these books students see mathematics in a different context while they use reading as a form of communication (p. 27). The use of children’s literature in the area of mathematics greatly influences learners and learning principles, the learning environment, curriculum formation, and assessment strategies in an array of positive manners. Integrating children’s literature in the mathematics classroom provides a new way for students to experience the subject matter, a unique view that typical textbooks cannot provide. Teaching students with various learning styles and needs means Children’s Literature and Math 4 differentiating the material whenever possible, and children’s literature offers a unique link to the core subject area of mathematics. Learners and Learning Students have diverse learning needs, and through offering multiple instructional methods, teachers can best meet the needs of the children in their classrooms. The National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (NCTM) asserts that students need opportunities to be active constructors of mathematical knowledge (Whitin & Wilde, 1992). When teachers create these opportunities to allow for discovery, students are able to truly see what they are learning, and the curriculum becomes both meaningful and purposeful. Through the integration of children’s literature into mathematics, learners are able to build connections between math and their lives, explore concepts more freely, gain positive attitudes toward the subject matter, and enhance their academic achievements. Building Math-to-Self Connections The NCTM (2000) named “connections” as a separate process standard for mathematics. Thus, creating and identifying the links among math concepts as well as those that relate to students’ own interests and experiences is crucial if the children are to understand the efficacy of mathematics. The NCTM notes that the value of mathematics resides largely in the extent to which it is useful in the course of some purposeful activity for the students (NCTM, 1989). If students do not build those connections, the subject is void of purpose in their lives, and they will lose interest. Children’s literature offers students another opportunity to make meaning and create connections between mathematics and their own lives (Austin, 1998). These possible links are often missed because students constantly ask the question “how will I use this in my life?” And Children’s Literature and Math 5 too often, teachers are unable to give satisfying responses, leaving students feeling deprived of a use of the subject matter they are learning. Through children’s literature, mathematics becomes more than just “a prescribed set of algorithms to master” as it transfers to “a way of thinking about their world” (Whitin & Gary, 2004, p. 394). Natural connections between the student and mathematics create new opportunities for learning. Children’s literature allows students to personalize their own learning experiences because they can “enter the story at their own levels of mathematical curiosity” (Jenner, 2002, p. 169). This type of learning allows students to tailor the material so it becomes relevant in their own lives. It is imperative for teachers to draw from their students’ funds of knowledge because the schema that children already possess allows them to understand pieces of information better. Stories can be open invitations for students to make connections from their own interests and background experiences to various math concepts (Whitin & Gary, 1994). Integrating literature into the mathematics curriculum also provides an authentic setting for observing math in the real world, allowing it to possess real meaning in the lives of students (Ward, 2005). Students gain the perspective of seeing mathematics used in real, though possibly fictional, scenarios, understanding its use outside of the math classroom. Math becomes a process instead of just a set of tasks to learn. Ideally, students will begin making math connections with books they selfselect to read (Shatzer, 2008). Once teachers instill the strategy of making connections between a reader and the mathematics in the literature, the students will become independent learners, identifying associations on their own for their own meaningful purposes. Exploring Concepts The emphasis in the math classroom is often on correct answers, with very little attention being devoted to helping students develop conceptual ideas. Children’s books have an ability to Children’s Literature and Math 6 provide students with a safe way to explore mathematical concepts when they may not otherwise do so (Jenner, 2002). This nonthreatening avenue is crucial if students are to have the freedom to explore common mathematical concepts. “Children’s understanding of mathematics can be sparked and sustained with literature,” and it is often just the ember a child needs to ignite their conceptual insight (Jenner, 2002, p. 169). Zemelman, Daniels, and Hyde (1998) assert that mathematics is a true science of patterns and relationships, and it is thorough grasping these patterns that students are able to fully understand the major concepts. For instance students already have a schema for a story framework, such as recognizing the beginning, middle and end. Students have the ability to utilize this type of foundational knowledge to grasp new understandings (Conaway & Midkiff, 1994). Because students are not encountering new manners of presenting the information, such as the case may be in a mathematics textbook, they are able to solely focus on the new concepts. Children’s books also typically have patterns as their underlying structure. Because both children’s literature and math rely on patterns as their basic foundation, children can easily identify important concepts that connect the two (Moyer, 2000). Learning about and identifying patterns is an effective process that leads to connections and comprehension Teachers should also explore the concept of using stories for unintended mathematical understanding (Jenner, 2002). Not all stories need to relate to math for ideas to become concrete to the students in the classroom. Many books contain isolated scenes that may be used to springboard a student to a mathematical topic. For instance, Usnick, McCarthy, & Alexander (2001) delineate how an upper elementary school classroom explored probability through an idea sparked in L’Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time. The students investigated how many socks were in Mrs. Whatsit’s drawer, working with concepts such as attribute sets and the difference between Children’s Literature and Math 7 replacement and non-replacement in probability. Stories like this provide natural contexts for word problems, and when students encounter these challenges within the literature, they are able to disregard the unfamiliar vocabulary and focus on the larger concepts (Ward, 2005). They focus on solving the problem instead of the problem itself. Children’s literature provides a natural and meaningful context for numbers because mathematical concepts are naturally embedded in story situations (Whitin & Wilde, 1992). Attitude Adjustments Boidy (1994) asserts that storytelling, the strategy by which children’s literature is integrated into the mathematics curriculum, can lead to more positive attitudes toward learning mathematics. Students with varying opinions toward the subject matter are presented with a new lens through which they view mathematics. For many children, math becomes something fun and different. Children’s literature can also be used to engage students who suffer from math anxiety (Hunsader, 2004). Tobias (1993) defines “math anxiety” as the tension and anxiety a person feels when required to manipulate numbers and/or solve mathematical problems. Children’s books can provide a new access point to the information to stray students from focusing on and being overwhelmed by the presence of numbers, algorithms, and problems to be solved. Because the use of children’s literature in mathematics allows students from a wide variety of abilities to access the concepts, most students have an entrance to experiencing some level of success (Shatzer, 2008). Also, teachers can use examples from literature to reassure their students that not everyone grasps mathematical concepts quickly. Whitin and Wilde (1992) speak of Gerry Oglan encouraging a positive attitude toward mathematics in his young son by reading him a book about various counting strategies, Two Ways to Count to Ten. This story allows students to Children’s Literature and Math 8 see there are multiple ways to count and encourages discussion about the way that is most effective for each individual child. Situations and discussions that may be sparked by children’s literature positively affect attitudes because the students are no longer inhibited by the thought that there is only way to find or view a correct answer. Mathematics becomes more about the process and less about the product. Learning Environment The use of children’s literature fosters a positive classroom community by giving students a common experience upon which they can build a base of knowledge. Vygotsky suggested that socially meaningful activities lead to higher mental processes (Moyer, 2000). Thus, reading books to build mathematical understanding creates a cohesive social atmosphere in the classroom. Discourse, room arrangement, and student groupings are all greatly influenced by the use of children’s literature in the mathematics classroom. Discourse The main purposes of creating a set discourse in one’s classroom are to help students become aware of others’ strategies and perspectives as well as clarifying and expanding their own thinking (McDuffie & Young, 2003). Developing an environment that fosters discourse in the context of mathematics can be quite difficult. Students who are not used to talking about mathematical concepts and terms may often be reluctant to speak up in class or participate in discussions (McDuffie & Young, 2003). The frequency of numbers and seemingly foreign terms may intimidate students. Schell (1982) argues that mathematics has some of the most complex content area material to read because it presents more concepts per word, sentence, and paragraph than any other core subject. Adams (2003) also claims that students are challenged by mathematic terms to many words that possess alternative, everyday meanings. For instance, Children’s Literature and Math 9 “product,” “ruler,” and “base” all have definitions outside the mathematics curriculum. Thus, providing an accessible language for students in the context of mathematics is absolutely vital. Children’s literature celebrates math as a language and provides students with the words, symbols, and images to use. It showcases the terminology in a manner that is easy to understand. Mathematics is, in fact, a natural communication system (Whitin & Wilde, 1992). Students need to be provided with a safe way to enter the language of mathematics if it is such a mode of communication, and reading trade books offer that appeal. Allowing opportunities for discourse in both reading and mathematics instruction promotes “children’s oral language skills as well as their ability to think and communicate mathematically” (Moyer, 2000, p. 246). Mimicking mathematical language from literature enables students to access the terms and creates a common language to be used in the classroom. One of the appeals to using trade books in elementary mathematics is their child-friendly nature. Not all books need to necessarily relate to mathematics specifically. Rather, they must solely spark a topic to discuss in relation to math. Students of all abilities are able to participate in such discussions because the subject matter does not require a correct answer; the teacher solely desires a response to the literature (Lewis, Long, & Mackay, 1993). Students are asked to relate the literature to mathematics, but it may not even be a problem that merits a “right” response. The main goal can be to connect mathematics to one’s life, and there is clearly no correct answer for such a prompt. Creating the foundations for both language and mathematical ideas in the elementary grades is extremely important in the larger course of a child’s development. The key abilities that are developed will serve children well in communicating mathematically throughout their lives (Moyer, 2000). Children’s Literature and Math 10 Through the use of children’s literature in the math classroom, a set of classroom discourse is developed that can be shared among all of the students (Jenner, 2002). It is this way of talking that allows students to clarify and expand their own thinking, and it leads to a classroom built upon deeper understanding. This communication helps students form links between their informal ideas and the abstract symbolism of many mathematical concepts (Moyer, 2000). Students often enjoy discussing stories they read on their own or those they have shared with them. When teachers use literature to discuss a mathematical idea, the natural discourse that follows allows students to engage in communicating in a meaningful manner (Lewis, Long, & Mackay, 1993). Ideally, students create relationships through this discourse, as all the children have at least this one manner of understanding subject matter in common. It is important to note that discourse transcends oral communication into written activities. Writing can play a powerful role in constructing mathematical understanding (Lewis, Long, & Mackay, 1993). Communication is a crucial part of mathematics, as the precision of the ideas is a result of the language used. If students are able to use both written and oral forms of language, the students will gain addition methods of expressing their ideas. There are many ways to use writing to emphasize mathematical discourse. The NCTM (1989) recommends that teachers provide opportunities for students to parallel stories in children’s books through writing stories with the appropriate mathematical concepts. Lewis Long, and Mackay (1993) highlight a second grade class of students mirroring The Doorbell Rang by Pat Hutchins, using dividing a whole instead of dividing a set of objects. Teachers can also engage students by allowing them to write answers to problems, write letters to friends about mathematics, or keeping a math journal to document their reflections to what they learn (Lewis, Long, & Mackay, 1993). Through Children’s Literature and Math 11 writing, students can learn new ideas, foster connections, and respond to mathematic concepts and ideas. Student Groupings and Room Arrangement There are many ways to group students that create opportunities for success with children’s literature in the math classroom, and no one way is the most effective for every classroom and situation. A teacher must understand his or her students and gauge what will work best for them. When using children’s literature in mathematics, careful thought must be put into how one arranges the students in a classroom. One effective grouping method is through creating shared reading experiences. Through dividing one’s students into groups of two or three, children are able to make mathematical connections and discuss their conjectures in a safe environment where their informal language is also celebrated (Jenner, 2002). When fear of an insufficient vocabulary inhibits a child from experiencing the material, the educational value of the activity is lessened. Another valuable method for utilizing children’s literature in math is using books to create group problem-solving tasks. It is through these challenges and allowing students to work together that children learn to communicate their mathematical ideas to one another and also consider alternative viewpoints (Lewis, Long, & Mackay, 1993). It is rare in math for young students to consider more than one answer as a valid possibility, but when using math in a literature context, just that can occur. Group discussions foster discussion and allow children to challenge their peers, directing the class to a more thorough understanding of the concepts. Teachers can create a mathematics book corner for students to read the books or listen to them on tapes or CDs. Students can independently read or listen to the literature to privately explore the math concepts; the students may also just want to encounter a quality piece of literature. To appeal to the whole class setting, the teacher can project the book via a projector Children’s Literature and Math 12 for the class to read together (Gailey, 1993). When teachers carefully consider the outcomes of grouping and arrangement of mathematics literature in the classroom, new possibilities for discourse are created, and children can be exposed to novel ideas. Learning is enriched through the use of children’s literature in the math classroom as students listen, read, write, and discuss mathematical ideas (Gailey, 1993). Curriculum and Instructional Settings The traditional method of learning math through individualized work with only paper and pencil assignments impedes student engagement and can halt the math learning process for many students (Stipek, Salmon, Givvin, Kazemi, Saxe, & MacGyvers, 1998). Callan (2004) delineates how students can relate math to their daily lives through literature. The transfer of knowledge from the classroom to the real world is one that is extremely important throughout education. Children’s literature breaks down the idea that learning mathematics and living mathematics are two different things (Whitin & Wilde, 1992). Within a meaningful context, students can extend their understanding of basic mathematical principles. Thus, incorporating mathematics into various areas of the curriculum is not a mere suggestion; it is essential to maximize student learning opportunities. Choosing Books When deciding which books to use in a classroom to enhance the teaching of mathematics, it is absolutely crucial to make sure the books are high-quality literature. The same standard that exists for choosing books in Language Arts must transfer to the literature used in the math classroom. The following are guidelines instructors must follow when selecting books: Teachers must look for an author’s use of rich language, descriptive writing, and engaging illustrations if they are included (Gailey, 1993) Children’s Literature and Math 13 The pieces of literature must have the “wow” factor to best appeal to all students, including both the visual and verbal appeal to an audience (Hellwig, Monroe, & Jacobs, 2000) The books must also be mathematically accurate, correct, and current in their social and economic setting (Gailey, 1993) If the previous standards exist for book choice, the literature used will be that of superior quality, naturally inviting children to be a part of the story while transferring accurate and relevant mathematics into their lives. Children’s books provide access to student exploration and discussion in manners that do not always develop naturally from subject-area textbooks (Kinniburgh & Byrd, 2008). Literature enhances and offers a supplement to the textbook, showcasing an authentic use of the material. However, not all children’s books relating to mathematics are appropriate to use in one’s classroom. Careful selection of books to integrate the subjects is necessary to ensure that connections are “authentic, not contrived; they should help children learn to think about mathematical ideas as ways of expressing relationships rather than discrete bits of information to be memorized and retrieved (Hellwig, Monroe, & Jacobs, 2000, p. 138). If students are to be exposed to material that is meaningful to them in their lives, then the teacher must take great care and consideration when choosing the literature to showcase in his or her classroom. It is important for teachers to consider books intended for a variety of grade levels. Whitin (2002) found that picture books intended for younger primary grades benefit mathematics instruction for upper grade students because they can extend the often times abstract mathematical concepts. The older children enjoy the success they find in understanding the simple text. They are free to focus on the ideas and mathematical language because they do not Children’s Literature and Math 14 have to strive to make meaning out of a difficult, challenging piece of writing. Just as older students enjoy books written for primary-grade students while exploring mathematical ideas, books written on a higher reading level can be read aloud to younger students according to the same rationale (Midkiff & Cramer, 1993). Children often connect to the situations they hear and read about even if the actual text is written in a complex manner. Both written text and illustrations provide opportunities to explore mathematical ideas (Moyer, 2000). Thus, younger and older children alike can utilize the pictures and words in literature to extend their conceptual knowledge. Gailey (1993) emphasizes four broad categories to separate the trade books that are appropriate for supplementing mathematics instruction. First, there are numerous counting books that are typically identified by colorful illustrations and their link to number concepts. The second category is the number book. These books highlight a specific number to enhance the understanding of its meaning. The third type of book involves miscellaneous storybooks. In this type of literature, the math concept may be touched on, but it is not the main focus. The last grouping calls for concept, or informational, books. These books explore a specific mathematical concept, but they are written in an entertaining manner for the reader. Extending these four categories is another literature realm: rhymes and poetry. These pieces often introduce a number or reinforce a specific concept or operation. Combining texts from all four of the categories provides students with a balanced library of literature to use in the mathematics classroom. Beyond the Book Children’s literature has traditionally only found its place in the physical world of text; however, due to technological advances, the Internet is now a large resource for children’s books and extension activities. When carefully integrated, the Internet can allow students to travel to Children’s Literature and Math 15 new places and experience novel responses to children’s literature (Leu, Castek, Henry, Coiro, & McMullan, 2004). Internet-based books and activities provide the same possibilities for meaningful conversation, authentic investigations, and new connections. As the classroom becomes increasingly more technologically advanced, teachers must utilize the new modes of communication available. The Internet can make literature seem like an active, alive part of the classroom, engaging students while inviting them to learn the content. Linking the Curriculum The idea of integrating the curriculum is not new. Rather, Dewey (1938) proposed an integration of knowledge and experience in the classroom. Currently, there is a wide push for developing a curriculum in which all students can experience success and learn authentically. Terms like coherent curriculum, thematic teaching, and differentiated instruction are often present in modern research and teacher preparation literature (Olness, 2007). All of these models stress that students learn best when they learn through their personal learning styles, typically gaining access to the material through several sources. The Principles and Standards for School Mathematics highlight the need for fostering connections between mathematics and other disciplines in the curriculum (NCTM, 2000). Recognizing the role of mathematics in relation to other core subjects is a key ingredient to grasping the usefulness of the material. Integrating literature into the mathematics classroom becomes increasingly more important as students enter the upper grades because the concepts become more abstract in their nature, and the links created help students see meaning and purpose in the principles being taught (Kinniburgh & Byrd, 2008). Today’s teachers face standards in a wide variety of realms: school, state, and national. With No Child Left Behind requiring school districts and states to publicize the progress of the Children’s Literature and Math 16 schools through report cards, there is little leeway regarding the designated curricula (NCTM, 2004). Integrating the curriculum can help teachers cover the required areas from their state’s standards, allowing more literature to be read and objectives taught (Kinniburgh & Byrd, 2008). Teachers maximize the topics covered given the time constraints by linking the subject matter. The use of children’s literature can also demonstrate that math extends beyond just a certain time of the school day, and it is an important part of one’s daily life (Franz & Pope, 2005). Modeling how math is utilized outside of the math classroom allows students to grasp its relevance in their own lives. Assessment Assessment is an integral part of a teacher’s instruction, as he or she must gauge student progress and then adjust the teaching accordingly. The NCTM (2002) asserts “assessment should support the learning of important mathematics and furnish useful information to both teachers and students (p. 22).” Probing to see what students know needs to serve more of a purpose than just passing a standardized test. Children deserve a chance to explain their understanding of the concepts. Because students have different learning styles, they should also be presented with a variety of assessment opportunities (Olness, 2007). Whitin and Gary (1994) argue that students need support to best represent their mathematical understanding through various forms. Some viable options include written and oral language, drawing, threedimensional artifacts, drama, and other modes that may be appropriate for specific students. As teachers increase their students’ options for expression, they increase their students’ avenues for understanding (Whitin & Gary, 1994). The NCTM (2002) declares that assessment should be done for the students, not merely to the students. The ultimate purpose should always be to guide instruction to best enhance student learning. Children’s Literature and Math 17 Student Achievement The traditional method of paper and pencil learning in the math classroom often contributes to low achievement levels in mathematics (Stipek, Salmon, Givvin, Kazemi, Saxe, & MacGyvers, 1998). This method of assessment does not allow students to thoroughly represent their conceptual understanding about the subject matter. Wilde (1998) found that children’s literature deepens mathematical understanding while allowing students to think and reason in a new manner. Boidy (1994) sought to increase student achievement through curriculum integration as well as providing means for alternative assessments. He found that by connecting core subjects, the students transferred knowledge better and were more able to connect the material to their everyday lives. His findings indicate that the integration of children’s literature into the mathematics curriculum led to higher student achievement. Language proficiency and math ability appear to be linked, another positive outcome of this example of curriculum integration (MacGregor & Price, 1999). As students become increasingly developed in their language abilities, perhaps through a submersion of quality children’s literature, their math capabilities also improve. Although more research must be done on the theory regarding heightened student achievement, it is important to understand the suggested findings that students can achieve more in both math and literacy when the two subjects are intertwined. Teachers are able to notice an escalation in the thinking regarding mathematical tasks when children’s literature is involved. In reviewing teachers’ comments about their students’ abilities, Clarke (2002) found that children were better at explaining their mathematical reasoning and strategies, more persistent on difficult tasks, and thought more about what they learned. Enhanced comprehension about the topic often leads to higher grades, and math scores Children’s Literature and Math 18 have increased when math strategies are connected with literature experiences (Jennings, 1992). Teachers need to provide students with a variety of access points to the curriculum, and children’s literature provides another viable method for success in mathematics. Extension Activities Using children’s literature in the mathematics classroom creates authentic possibilities for extension activities that focus on creating a thorough understanding of math concepts (Conaway & Midkiff, 1994). Children’s literature presents discovery-learning opportunities and explores new methods of gaining and expressing knowledge. The selected extension activities should provide students with authentic hands-on opportunities to survey the connections between literacy and mathematics (Morrow & Gambrell, 2004). One example of an extension activity is using children’s literature to create mathematical games based on various concepts, such as sorting, geometry, or standard units of measurement (Hopkins, 1993). As children experience the freedom to delve deeper into the concepts, they are truly demonstrating their working understanding of the material. The use of picture books and extension activities creates positive reactions, enjoyment, and a sense of confidence in children (Shatzer, 2008). When mathematics is viewed in such a positive light, the focus is drawn from the formalized assessment that so many children dread. Extension activities provide an additional mode of assessment outside of the traditional pencil and paper test, and children still possess the same opportunities to display their knowledge and understanding. Comprehension Hyde (2006) suggests teachers using various comprehension strategies to assess a student’s grasp of the mathematical concepts in relation to the children’s literature. Asking questions, making connections, visualizing, inferring, predicting, determining importance, and Children’s Literature and Math 19 synthesizing are all valid ways for teachers to foster the links between mathematics, children’s literature, and the student’s life. This use of strategies is typically tied to a literacy activity; however, since the children’s literature is integrated into the mathematics curriculum, they become practical forms of expressing understanding. Strategies of questioning, connecting, predicting, etcetera are just as useful in mathematics as in language arts. The same concepts are often explored and given different terms in mathematics, such as conjectures and proofs. Teachers should also encourage their students to respond to the stories they read through poetry, drama, art, oral discourse, or writing (Whitin & Wilde, 1992). Allowing such a wide range of responses invites students to view math from a wide array of perspectives, which deepens and broadens their understanding. Offering students the chance to showcase their understanding of various concepts by providing them with a choice in their manner of expression ensures that the form of assessment will not inhibit the display of knowledge. Rather, a student’s comprehension of the mathematical ideas truly reflects his or her grasp through the most appropriate means. Conclusion Children’s literature holds a valid place in the elementary classroom. In both research and practice, educators assert the positive affect children’s literature can have on mathematics. Trade books provide opportunities for connections between students and the subject matter, exploration of concepts, engagement and positive attitudes about math, new possibilities for discourse, differentiation with regards to student grouping, links to other core subjects in the curriculum, and new, diverse, and authentic modes of assessment. The use of children’s literature in the mathematics classroom creates a community of learners who experience relevant mathematics as it comes to life via the words and pictures in a text. Implications Children’s Literature and Math 20 Many implications can be drawn from the information, both research and teacher-based, regarding the best ways to use children’s literature in the mathematics classroom. The information suggests the use of trade books positively influences student learning, the learning environment, curriculum development, and possibilities for assessment. Thus, teachers must consider the benefits children’s literature can have in their mathematics classroom. As a future educator myself, I will speak broadly about the process teachers should follow when integration these two core subjects. Because the foremost goal of the mathematics classroom is the teaching of concepts, teachers must be aware of the standards and units they need to cover in a given amount of time. After the general subjects are selected, review the various lists of children’s literature (Whitin & Wilde, 1992; Gailey, 1993; etc.) to identify several possible books to use that will enhance a concept. Examine literature across difficulty levels and genres since the subject matter may have a broader appeal when used in this context (Whitin , 2002). These pieces of literature should then be reviewed according to the criteria set forth by Gailey (1993). The books must: Use rich language Present descriptive writing Showcase engaging illustrations, if they are present Accurately and correctly represent the mathematical concepts Be current and correct in the current social and economic setting Once the teacher chooses the literature to use, he or she must decide how to effectively integrate it into the curriculum to serve a clear purpose. Deciding to incorporate shared reading, a literacy center, or whole group read alouds makes a difference in the day-to-day use of the literature. Regardless of the chosen method of using the books in the classroom, the teacher should Children’s Literature and Math 21 introduce the literature to the class as it correctly corresponds to the subject matter. If the literacy center houses only books on geometry as the class is studying algebra, the purpose and effectiveness of the literature are missed entirely. The teacher should engage the students in a discussion about the literature, as is deemed appropriate, to increase and enhance the common discourse (Lewis, Long, & Mackay, 1993). After the books have been read, utilized, and discuss, teachers can choose to create extension activities that expand upon the issues in the literature. For instance, a fourth grade teacher effectively challenged her students to write their own factorial stories after reading Anno’s Mysterious Multiplying Jar (Whitin & Wilde, 1992). The use of such a lesson not only expanded on a concept explored in literature, but it effectively integrated an authentic literacy activity into the curriculum. Implementing such an activity can cover both language arts and math standards. Assessment is necessary during and after any lesson is taught to maximize benefits for both the students and the teacher. Instructors can use informal assessments to monitor how the students are discussing the literature and concepts since the discourse was already put into place. Regardless of the form of assessment, such as tests, quizzes, or additional activities, students must have the opportunity to explain their understandings. Because the curriculum models how language can be integrated into math, the assessment should clearly demonstrate the connection (Morrow & Gambrell, 2004). Students should be able to express their knowledge in a manner that appeals to their learning styles, and teachers need to identify whether the literature helped extend their thinking of the concepts. This is where assessment is beneficial for both students and teachers; the children can explain their understanding, which demonstrates achievement and guides future instruction, and the teachers can assess if they should continue using that piece of Children’s Literature and Math 22 literature with that concept. If the text does not extend the students’ knowledge, shine clarity on a topic, foster a connection with a child, or make a connection between the mathematics and the real world, the book should be reevaluated as a piece of the curriculum. The above process may seem daunting, but to provide the best instruction for students, teachers need to carefully ponder how the curriculum and activities benefit the students and the actual content matter. When effectively implemented, integrating children’s literature into the math curriculum increases student achievement and positively influences attitudes toward the subject (Shatzer, 2008). Students enjoy the literature and enjoy mathematics. The material becomes relevant as students see its presence in fictitious or real-world examples, and learning the jargon, concepts, and main ideas now serves a purpose for those students who cannot rationalize learning about math. Teachers can utilize a variety of professional literature to help guide their choice of literature to use in the classroom. However, I found some more helpful than others, including one that should be on every instructor’s shelf of professional books. Whitin and Wilde (1992) provide countless examples of using literature to enhance mathematics teaching in their book Read Any Good Math Lately? This book highlights children’s books according to topic, including many examples of extension and assessment activities. They also divide the books according to grade levels (K-2, 3-4, 5-6) to best identify which books are most appropriate for a specific age. The information in this book is both practical and relevant, and it also explains the theoretical base behind the benefits of using literature in the math classroom. The following book list was compiled from the children’s books mentioned in all pieces of literature reviewed for this paper. The chosen books hopefully span a variety of topics, units, grades, and difficulty to best assist a teacher of any level. This is surely not a complete list of the Children’s Literature and Math 23 useful, quality literature available, but it should provide a good base of trade books for teachers to survey for possible use in their mathematics classrooms. Book List Author Adler, David Adler, Irvin Adler, Irvin & Ruth Alain, B. Allen, Pamela Anno, Mitsumasa Asimov, Isaac Axelrod, Amy Aylesworth, James Balain, Lorna Ball, Johnny Bang, Molly Barton, Byron Base, Graham Berenstain, Stan and Janice Birch, David Bishop, Claire Blackstone, Stella Bogart, Jo Ellen Bond, Michael Brandenberg, Franz Briggs, Raymond Brown, Marc Bucknall, Caroline Burningham, John Burns, Marilyn Burton, Virginia Lee Calmenson, Stephanie Carle, Eric Book Title 3D, 2D, 1 D Base Five Calculator Riddles How Tall, How Short, How Far Away? Roman Numerals Mathematics Numbers Old and New One, Tow, Three, Going to Sea Mr. Archimedes’ Bath Anno’s Counting Book Anno’s Counting House Anno’s Hat Tricks Anno’s Math Games Anno’s Mysterious Multiplying Jar Socrates and the Three Little Pigs How Did We Find Out about Numbers? Pigs will be Pigs One Crow Wilbur’s Space Machine Go Figure! A Totally Cool Book About Numbers Ten, Nine, Eight The Three Bears The Eleventh Hour: A Curious Mystery Bears on Wheels The King’s Chessboard The Five Chinese Brothers Bear in a Square Ten for Dinner Paddington at the Zoo Aunt Nina and Her Nephews and Nieces Six New Students Jim and The Beanstalk Hand Rhymes One Bear All Alone The Shopping Basket Spaghetti and Meatballs for All! The Greedy Triangle Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel Ten Items or Less The Very Hungry Caterpillar Children’s Literature and Math 24 Carolna, Philip Carroll, Lewis Carter, David Charosh, Mannis Choos, Ramona G. Clark, Ellen Clement, Rod Coats, Lucy Cohen, Donald Crawford, Thomas Crews, Donald Cristelow, Eileen Cummings, Pat Cushman, Jean Davis, Douglas F. Day, Alexandra De Paola, Tomie De Regniers, Beatrice Schenk Dee, Ruby Demi Dennis, Richard Dodds, Dayle Ann Drobot, Eve DuBois, William Duffy, Betsy Dunbar, Joyce Durango, Julia Eastman, Philip Eberts, Marjorie & Margaret Gisler Ehlert, Lois Eichenberg, Fritz Elkin, Benjamin Ellis, Julie Emberly, Barbara Emberly, Ed Ernst, Lisa Campbell and Lee Estes, Eleanor Ewing, Susan Falconer, Ian Feelings, Muriel Fey, James Florian, Douglas Numbers Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland Over in the Meadow Number Ideas through Pictures Straight Lines The Ellipse Sorting Understanding Numbers Counting on Frank Neil’s Numberless World Calculus by and for Young People Betsy the Babysitter Sticky Stanley Ten Black Dots Five Little Monkeys Jumping on the Bed Five Little Monkeys Sitting on a Tree Clean Your Room, Harvey Moon! Do You Wanna Bet? Your Chance to Find Out About Probability There’s An Elephant in The Garage Carl Goes Shopping The Popcorn Book So Many Cats Two Ways to Count to Ten One Grain of Rice: A Mathematical Folktale Fractions Are Parts of Things Minnie’s Diner: A Multiplying Menu Money, Money, Money: Where It Comes From, How to Save It, and Make It The Twenty-One Balloons The Math Wiz Ten Little Mice Cha-Cha Chimps Big Dog, Little Dog: A Bedtime Story Pancakes, Crackers, and Pizza: A Book of Shapes Fish Eyes Dancing in the Moon Six Foolish Fishermen What’s Your Angle, Pythagorus? A Math Adventure One Wide River to Cross The Wing on a Flea The Tangram Magician The Hundred Dresses Ten Rowdy Ravens Olivia Counts Moja Means One: A Swahili Counting Book Long, Short, High, Low, Thin, Wide A Pig is Big Children’s Literature and Math 25 Friedman, Aileen Froman, Robert Gag, Wanda Gardner, Martin Geisert, Arthur Geringer, Laura Giff, Patrick Reilly Giganti, Paul, Jr. Gisler, David Greenes, Carole Griest, Lisa Grifalconi, Ann Grossman, Virginia & Sylvia Long Hammond, Franklin Haskins, Jim Hightower, Susan Hoban, Russell Hoban, Tana Hooks, William Hoopes, L. L. Hopkins, Lee Bennett Howard, Katherine Hrada, Joyce Hutchings, Amy and Richard Hutchins, Pat A Cloak for the Dreamer A Game of Functions Angles are Easy As Pie Less Than Nothing Is Really Something Rubber Bands, Baseballs and Doughnuts The Greatest Guessing Game Venn Diagrams Millions of Cats Perplexing Puzzles and Tantalizing Teasers Roman Numerals I to MM A Three Hat Day The Candy Corn Context Each Orange Had Eight Slices How Many Birds Flew Away? How Many Snails? Addition Annie I Can. Can You? Jake’s Closet Opossums in a Tree Rebecca’s Party The Magic Shapes Which Hare is Where? Lost at the White House The Village of Round and Square Houses Ten Little Rabbits Ten Little Ducks Count Your Way through Africa Count Your Way through Canada Count Your Way through China Count Your Way through Germany Count Your Way through Italy Count Your Way through Japan Count Your Way through Korea Count Your Way through Mexico Count Your Way through Russia Count Your Way through The Arab World Twelve Snails to One Lizard: A Tale of Mischief and Measurement Ten What? Cubes, Cones, Cylinders, & Spheres Is It Larger? Is It Smaller? The Seventeen Gerbils of Class 4A My Own Home Marvelous Math: A Book of Poems I Can Count to One Hundred…Can You? It’s the 0-1-2-3 Book The Gummy Candy Counting Book One Hunter Children’s Literature and Math 26 Hynard, Julia Irons, Rosemary and Calvin James, Elizabeth & Carol Barkin Johnston, Tony Joyce, William Juster, Norton Kahl, Virginia Kasza, Keiko Kaye, Marilyn Keenan, Sheila Kensler, Chris King, Clive Knowlton, Jack Koscielniak, Bruce Krahn, Fernando Krauss, Ruth Kredenser, Gail and Stanley Mack Latham, Jean L’Engle, Madeleine Leedy, Loreen Lenssen, Ann LeSieg, Theo Lewis, J. Patrick Linn, Charles Lionni, Leo Long, Lynette Luce, Marnie Madden, Don Martin, Bill Mathews, Louise Mathis, Sharon Mayer, Mercer McDonald, Collin McGrath, Barbara Barbieri McKee, Craig & Margaret Holland McInnes, John The Doorbell Rang Percival’s Party Mirror Mirror What Do You Mean by “Average?” Farmer Mark Measures His Pig George Shrinks The Phantom Tollbooth How Many Dragons Are Behind the Door? The Wolf’s Chicken Stew A Day with No Math What Time Is It? A Book of Math Riddles Secret Treasures and Magical Measures: Adventures in Measuring Time, Temperature, Length, Weight, Volume, Angles, Shapes and Money Me and My Millions Maps and Globes About Time: A First Look at Time and Clocks The Family Minus The Carrot Seed One Dancing Drum Carry On, Mr. Bowditch A Wrinkle in Time Measuring Penny Subtraction Action A Rainbow Balloon Ten Apples Up on Top! Arithme-Tickle: An Even Number of Odd Riddle-Rhymes Estimation Probability Inch by Inch Domino Addition Infinity: What Is It? Sets: What Are They? Ten: Why Is It Important? The Wartville Wizard Monday, Monday, I Like Mondays Ten Little Squirrels The Eagle Has Landed Bunches and Bunches of Bunnies The Hundred Penny Box Just A Mess Nightwaves The M&M’s Brand Color Pattern Book The M&M’s Counting Book The M&M’s Count to One Hundred Book More M&M’s Math The Teacher Who Could Not Count Duck’s Can’t Count Children’s Literature and Math 27 McMillan, Bruce Merriam, Eve Merrill, Jean Milne, A. A. Moncure, Jane Moore, Inga Morris, Ann Mosel, Arlene Moss, Jeffrey Most, Bernard Munsch, Robert Murphy, Stuart Myers, Walter Dean Myller, Rolf Nagda, Ann Whitehead Naylor, Phyllis Nelson, JoAnne Nolan, Helen Neuschwander, Cindy O’Keefe, Susan Heyboer Packard, Edward Pallotta, Jerry Eating Fractions One, Two, One Pair! 12 Ways to Get to 11 The Toothpaste Millionaire Pooh’s Counting Book My Six Book Six-Dinner Sid Hats, Hats, Hats Tikki Tikki Tembo Five People in My Family The Littlest Dinosaurs The Paper Bag Princess A Pair of Socks: Matching Betcha! Bigger, Better, Best! Coyotes All Around Captain Invincible and the Space Shapes Just Enough Carrots Leaping Lizards The Mouse Rap How Big Is A Foot? Chimp Math: Learning About Time From a Baby Chimpanzee Tiger Math: Learning to Graph from a Baby Tiger Polar Bear Bath Eddie, Incorporated Count by Twos Half and Half How Tall Are You? The Magic Money Machine Neighborhood Soup One and One Make Two How Much, How Many, How Far, How Heavy, How Long, How Tall is 1000? Mummy Math: An Adventure in Geometry Sir Cumference and the Isle of Immeter Sir Cumference and the Sword in the Cone One Hungry Monster Big Numbers: And Pictures That Show How Big They Are! Apple Fractions Hershey’s Chocolate Math from Addition to Multiplication Hershey’s Milk Chocolate Weights and Measures Reese’s Pieces Count by Fives The Icky Bug Counting Book The Hershey’s Kisses Multiplication and Division Book The Hershey’s Kisses Subtraction Book The Hershey’s Milk Chocolate Fractions Book Twizzlers Percentages Book Children’s Literature and Math 28 Papy, Frederique Phillips, Jo Pienkowski, Jan Pinczes, Elinor Reed, Mary & Edith Osswald Rees, Mary Reimer, Luetta & Wilbert Ritchie, Alan Romano-Young Rosen, Sidney Russo, Marisabina Rylant, Cynthia Samton, Sheila Scarry, Richard Schwartz, David Scieszka, Jon & Lane Smith Selfridge, Oliver Sendak, Maurice Serfozo, Mary Seuss, Dr. Shapiro, Arnold Sheppard, J. Shotwell, Louisa Shub, Elizabeth Simon, Seymour Sitomer, Mindell Slobodkina, Esphyr Smith, David Smucker, Barbara Srivastava, Jane Stevens & Crummel Tang, Greg Thaler, Mike & Jerry Smath Thompson, Lauren Tompert, Ann Twohill, Maggie Ulmer, M. Viorst, Judith Twizzlers Shapes and Patterns Graph Games Exploring Triangles Sizes A Remainder of One Inchworm and a Half One Hundred Hungry Ants Numbers Ten In A Bed Mathematicians Are People Too Erin McEwan, Your Days Are Numbered Small Worlds: Maps and Map-Making How Far Is A Star? The Line-up Book Henry and Mudge: The First Book On the River Richard’s Scarry’s Best Counting Book Ever How Much Is a Million? If You Made a Million Millions to Measure Math Curse Fingers Come in Fives One Was Johnny Who Wants One? One Fish, Two Fish, Red Fish, Blue Fish The 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins Squiggly Wiggly’s Surprise The Right Number of Elephants Roosevelt Grady The Twelve Dancing Princesses Einstein Anderson, Science Sleuth How Did Numbers Begin? Zero Is Not Nothing Caps for Sale If The World Were A Village: A Book About the World’s People Selina and the Bear Paw Quilt Number Families Spaces, Shapes and Sizes Statistics Cook-A-Doodle-Doo! Math Potatoes: Mind-Stretching Brain Food Seven Little Hippos One Riddle, One Answer Grandfather Tang’s Story: A Tale Told with Tangrams Superbowl Upset Loonies and Toonies: A Canadian Number Book Alexander Who Used to Be Rich Last Sunday Children’s Literature and Math 29 Wadsworth, Olive Wahl, John and Stacey Walsh, Ellen Stoll Walton, Rick Watson, Clyde Weiss, Malcom Wells, Robert Wells, Rosemary Wildsmith, Brian Williams, Vera Wiseman, B. Wood, Audrey and Don Wulffson, Don L. Wylie, Joanne Zarro, Richard Zaslavsky, Claudia Ziefert, Harriet Zimelman, Nathan Earrings! The Tenth Good Thing About Barney Over in the Meadow I Can Count the Petals of a Flower Mouse Count House Many, How Many, How Many Binary Numbers Six Hundred Sixty-six Jellybeans! All That? Solomon Grundy Born on Oneday Can You Count to A Googol? Is A Blue Whale The Biggest Thing There Is? Bunny Money One, Two, Three A Chair for My Mother Morris Goes to School Piggies More Incredible True Adventures A More or Less Fish Story Do You Know Where Your Monster Is Tonight? How Many Monsters? The King of Numbers Count on Your Fingers African Style A Dozen Dogs: A Read-and-Count Story How The Second Grade Got $8,205.50 to Visit the Statue of Liberty Children’s Literature and Math 30 Bibliography Adams, T. (2003). Reading mathematics: More than words can say. The Reading Teacher , 56 (786-795). Austin, P. (1998, Spring). Math books as literature: Which ones measure up? The New Advocate 11 , 119-133. Boidy, T. (1994). Improving students' transfer of learning among subject areas through the use of an integrated curriculum and alternative assessment. IL: Saint Xavier University. Callan, R. (2004). Reading + Math = A Perfect Match. Teaching Pre K-8 , 34 (4), 50-51. Clarke, D. (2002). Making measurement come alive with a children's storybook. Australian Primary Mathematics Classroom , 7 (3), 9-13. Conaway, B., & Midkiff, R. B. (1994). Connecting literature, language, and fractions. The Arithmetic Teacher , 41 (8), 430-434. Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and Education. New York: Macmillan. Education, U. D. (2004, July 1). NCLB. Retrieved January 25, 2009, from Four Pillars of NCLB: http://www.ed.gov/nclb/overview/intro/4pillars.html Franz, D. P., & Pope, M. (2005). using children's stories in secondary mathematics. American Secondary Education Journal , 33 (2), 20-28. Gailey, S. (1993). The mathematics-children's literature connection. Arithmetic Teacher , 40, 258-261. Hellwig, S. J., Monroe, E. E., & Jacobs, J. (2000). Making informed choices: Selecting children's trade books for mathematics intruction. Teaching Children Mathematics Journal , 7 (3), 138-145. Children’s Literature and Math 31 Hopkins, M. H. (1993). Ideas: Mathematical games using children's literature. Arithmetic Teacher , 40 (9), 512-519. Hunsader, P. D. (2004). Mathematics trade books: Establishing their value and assessing their quality. The Reading Teacher , 57 (7), 618-629. Hyde, A. A. (2006). Comprehending math: Adapting reading strategies to teach mathematics, K6. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. Jenner, D. (2002). Experiencing and understanding mathematics in the midst of a story. Teaching Children Mathematics , 9 (3), 167-171. Jennings, C. M. (1992). Increasing interest and achievement in mathematics through children's literature. Early Childhood Research Quarterly , 7 (2), 263-276. Kinniburgh, L. H., & Byrd, K. (2008, January/February). Ten black dots and September 11: Integrating social studies and mathematics through children's literature. The Social Studies , 33-36. Leu, D., Castek, J., Henry, L. A., Coiro, J., & McMullan, M. (2004). The lessons that children teach us: Integrating children's literature and the new literacies of the internet. The Reading Teacher , 57, 496-503. Lewis, B. L., Long, R., & Mackay, M. (1993). Fostering communicating in mathematics using children's literature. Arithmetic Teacher , 40 (8), 470-474. MacGregor, M., & Price, E. (1999). An exploration of aspects of language proficiency and algebra learning. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education , 30, 449-467. Mathematics, N. C. (1989). Curriculum and evaluation standards for school mathematics. Reston, VA: NCTM. Children’s Literature and Math 32 McDonald, J., & Czerniak, C. (1994). Developing interdisciplinary units: Strategies and examples. School Science and Mathematics , 5-10. McDuffie, A. M., & Young, T. A. (2003). Promoting mathematical discourse through children's literature. Teaching Children Mathematics , 9 (7), 385-391. Midkiff, R. B., & Cramer, M. M. (1993). Stepping stones to mathematical understanding. Arithmetic Teacher , 40 (6), 303-306. Morrow, L. M., & Gambrell, L. B. (2004). Using children's literature in preschool: Comprehending and enjoying books. Newark, DE: International Reading Association. Moyer, P. (2000). Communicating mathematically: Children's literature as a natural connection. The Reading Teacher , 54 (3), 246-255. NCTM. (2000). Principles and Standards for School Mathematics. Reston, VA: NCTM. Olness, R. (2007). Using Literature to Enhance Content Area Instruction. Newark, DE: International Reading Association. Ronau, R. N., & Karp, K. S. (2001). Power over trash: integrating mathematics, science, and children's literature. Mathematics Teaching in the Middle School , 7 (1), 26-30. Schell, V. (1982). Learning partners: Reading and mathematics. The Reading Teacher , 35, 544548. Shatzer, J. (2008). Picture book power: Connecting Children's literature and mathematics. The Reading Teacher , 61 (8), 649-653. Stipek, D., Salmon, J., Givvin, K., Kazemi, E., Saxe, G., & MacGyvers, V. (1998). The value (and convergence) of practices suggested by motivation research and promoted by Children’s Literature and Math 33 mathematics education reformers. Journal of Research in Mathematics Education , 29 (4), 465-488. Tobias, S. (1993). Overcoming math anxiety. New York: Norton. Usnick, V., McCarthy, J., & Alexander, S. (2001). Mrs. whatsit "socks" it to probability. Teaching Children Mathematics , 8 (4), 246-248. Ward, R. A. (2005). Using children's literature to inspire K-8 preservice teachers' future mathematics pedagogy. The Reading Teacher , 59 (2), 132-143. Whitin, D. J., & Gary, C. C. (1994). Promoting mathematical explorations through children's literature. The Arithmetic Teacher , 41 (7). Whitin, D. J., & Wilde, S. (1992). Read Any Good Math Lately? Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. Whitin, D. (2002). The potentials and pitfalls of integrating literature into the mathematics program. Teaching Children Mathematics Journal , 8 (9), 503-504. Wilde, S. (1998). Mathematical learning and exploration in nonfiction literature. In R. Bamford, & J. V. Kristo (Eds.), Making facts come alive: Choosing quality nonfiction literature K8 (pp. 123-134). Norwood, MA: Christopher-Gordon. Zemelman, S., Daniels, H., & Hyde, A. (1998). Best practice: New standards for teaching and learning in America's schools (2nd ed.). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.