Running Head: BRIDGING THE GAP 1

advertisement

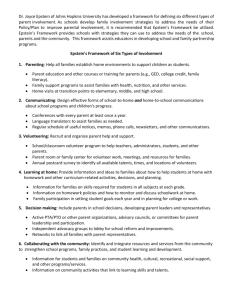

Running Head: BRIDGING THE GAP 1 Bridging the Gap: Increasing Parent and Family Involvement in the Early Education of English Language Learners Amy Kramer Vanderbilt University BRIDGING THE GAP 2 Abstract There is an extensive body of literature documenting the importance of parent and family involvement as well as its relationship to student academic achievement and overall success. This essay reviews part of that research and focuses specifically on how to connect with and involve the parents and families of English Language Learners in their children’s literacy education at the early elementary level. The essay begins by defining the positionality and framework from which the research was analyzed as well as explaining the context. The perspective of the analysis is largely focused on highly diverse and urban settings, the meaning of which are explained further throughout the essay. In addition, a rationale is provided in order to support the relevance and need for immediate attention with regards to parent and family involvement. The literature review of this essay is grouped into three major themes. The first theme focuses on how parent and family involvement looks different across different cultures, which is extremely important to understand when working with students from diverse backgrounds. The second theme of the literature review discusses the factors that often inhibit parent and family involvement from occurring, specifically in urban and highly diverse contexts. It is critical that educators are aware of both the meaningful contributions as well as the perceived shortcomings of the population in which they are working in order to best meet their needs. Finally, a large portion of the literature review is devoted to providing promising practices based on the research literature and discussing how the information can actually be implemented in schools. These promising practices for connecting with and involving the parents of English Language Learners in their children’s literacy education are organized by Epstein’s (1995) framework for six types BRIDGING THE GAP 3 of involvement. The six types of involvement described are: parenting, communicating, volunteering, learning at home, decision-making, and collaborating with community. Conclusively, future implications for the field of education are described. In this section, the need for professional development is discussed as well as the prospects that if the necessary steps are taken, the gap between home and school will begin to disappear. Bridging the Gap: Increasing Parent and Family Involvement in the Early Education of English Language Learners For as long as I have been studying education, I have taken a special interest in parent and family involvement. A large and growing body of research documents the importance of parent and family involvement as well as its positive correlations to academic success (HooverDempsey et. al, 2005; Giles, 2006; Barton, 2003; Epstein and Dauber, 1991; Epstein, 1995, Jeynes 2003, 2010; Araujo, 2009). As a future educator, I aspired to develop a better understanding of how to increase parent and family involvement in order to better serve my students. Over the course of being involved in the Learning, Diversity, and Urban Studies program, I became even more eager to gain further knowledge in regards to family involvement and specifically how it looks in diverse and urban contexts. As a part of my program of study, I began working as an intern for the Literacy Director of the preschool at St. Luke’s Community House, a United Way Family Resource Center that provides over forty programs to the residents of Old West Nashville. St. Luke’s is the only major social service agency in the area and brings various community agency partners together to provide specialty services to its population. The overall goal of St. Luke’s is to empower residents to improve their lives and their community. The organization serves what they refer to BRIDGING THE GAP 4 as a “working poor community,” and a majority of the population does not speak English as their first language (St. Luke’s Community House, 2012). St. Luke’s preschool, where I spent the majority of my time, is a sliding scale licensed program with a focus on Kindergarten readiness. The preschool is open during the weekdays from 6:30 am to 5:30 pm and accepts children from 6 weeks of age through 5 years (preKindergarten). The median annual family income of children enrolled in this program is $18,000 and nearly 90% of the children in the community qualify for free or reduced lunch in schools. In addition, 46% of the adults in the St. Luke’s community have not obtained a high school diploma and the adult education level averages 6th grade (St. Luke’s Community House, 2012). When I began my internship, one of St. Luke’s greatest struggles was getting the parents and families who have students enrolled in the preschool involved in their children’s education. In an interview that I conducted with the Literacy Director of St. Luke’s, she shared with me that the average number of parents in attendance at their Family Literacy Workshops is 2. Very little if any communication was occurring between the families and the teachers and the families’ voices were certainly not being heard. I was given the responsibility of serving as parental liaison at St. Luke’s, which allowed me gain realistic and helpful insights into my quest for gaining knowledge about increasing parent and family involvement, specifically in an urban context. My internship at St. Luke’s became the inspiration for my Capstone research topic and allowed me the experience to actually apply a great deal of the information that I was discovering from the process. Because I was interning at St. Luke’s for the Literacy Director of the preschool program, the specific framework for my research was centered on connecting with and involving the parents and families of English Language Learners at the early elementary BRIDGING THE GAP 5 level in their child’s literacy education. The preschool offers the Read to Succeed curriculum, a non-profit community initiative supported by businesses, foundations, grants, and in-kind donations, which works to increase awareness of the importance of literacy education. The idea behind Read to Succeed is that “by teaching these at-risk children early literacy skills they otherwise wouldn’t have, they have a greater chance to succeed in school and a lesser chance of getting into trouble” (United Way of Metropolitan Nashville, 2012). Although I am fully aware that not all learning contexts are the same, I believe that many urban and highly diverse settings share in similar struggles with regards to parent and family involvement and it is my hopes that my research will be transferable to multiple settings. In this essay, I will first describe the framework and positionality that I used while conducting the research as well as provide a rationale as to why my chosen topic is pertinent and deserves such immediate attention. I will then offer a review of the major themes of the literature including research-based suggestions for practice. Finally, I will reiterate the relevance of the topic at hand and the implications that it has for the field of education. Throughout this essay, I will address the matter of how to connect with and involve the parents and families of English Language Learners in their children’s literacy education at the early elementary level as well as why this topic deserves significant attention. Ultimately, I hope to work towards to a solution in order to begin bridging the gap between home and school. Framework and Rationale Before I begin reviewing the body of literature on parent and family involvement as it pertains to urban and highly diverse settings, I want to first address several of the languages that will be discoursed throughout this essay. The learners in which I will be focusing on in this essay are English Language Learners at the early childhood level. In the context of St. Luke’s BRIDGING THE GAP 6 Community House, where my interest in this topic truly began, the high number of English Language Learners meant that there was a great deal of diversity. In highly diverse areas, it is especially important to develop an understanding of parental involvement, as it can look very different across different cultures, making the matter at hand extremely relevant. Along with focusing on diversity, I will also be spending a large portion of my essay discussing parent and family involvement in regards to urban contexts. Though I use this term a great deal, it is very difficult to define. In the field of higher education, there is not a shared explanation of what is meant by the term “urban,” (Milner, 2012) which makes it challenging to clearly outline. In a recently published article, Milner (2012) offers three conceptual frames for how to define schools in urban educational environments. For the purposes of this essay, when I make a reference to the term urban, I am looking at it through the frame that Milner (2012) terms, “urban emergent,” to describe schools that are in relatively large cities but not as large as the major cities identified as part of the “urban intensive” category. When describing urban emergent, Milner (2012) states, “Although they do not experience the magnitude of the challenges that the urban intensive cities face, they do encounter some of the same scarcity of resource problems, but on a smaller scale” (p. 559). My positionality for this essay is very much reflected in the fact that my program is focused on diversity and urban studies. I have been studying these issues while visiting and working with diverse and urban populations throughout my time at Vanderbilt. Thus, my perspective relative to what I have researched has been shaped by these experiences. My internship experience has especially molded the way in which I have analyzed and reviewed the literature. For instance, I have specifically focused my attention on English Language Learners at the early elementary level because this is the population that I am serving at St. Luke’s. While BRIDGING THE GAP 7 researching, however, I have found that a majority of the literature is transferable and can be applied to multiple contexts. I have also focused my research on parent and family involvement with literacy education but have similarly discovered that the general promising practices for increasing involvement are necessary in order for involvement specifically pertaining to literacy education to be improved. Regardless of the context in which I chose to position my research, the relevance of parent and family involvement in the field of education cannot be denied. An extensive and growing literature provides evidence supporting the claim that parent and family involvement is important and has tremendous positive effects on student achievement and overall success (Hoover-Dempsey et. al, 2005; Giles, 2006; Barton, 2003; Epstein and Dauber, 1991; Epstein, 1995, Jeynes 2003, 2010; Araujo, 2009). Parent involvement has been positively linked to aspects of student success including teacher ratings of student competence, student grades, achievement test scores, lower rates of retention in grade, lower drop-out rates, higher on-time high school graduation rates, and higher rates of participation in advanced courses (Hoover-Dempsey et. al, 2005). Giles (2006) adds to this argument by stating, “The importance of parent involvement was identified by the school effectiveness movement of the early 1980s (Levine & Lezotte, 1990), and has long been advocated as a means of improving student achievement (Henderson & Mapp, 2002)” (Giles, 2006). There is no doubt about the fact that parent and family involvement is an important issue that deserves attention. In fact, Barton (2003) even lists parental participation as one of the 14 correlates of elementary and secondary school achievement, with several other correlates related to the home-school connection being included as well. Barton (2003) also provided, “Teachers are much more likely, in the case of parents from high-poverty schools, to report that lack of parental involvement is a moderate or serious problem” (p. 20). This means that parental and BRIDGING THE GAP 8 family involvement is of particular concern in urban and highly diverse settings. Jeynes (2003) notes, “As the stability of the American family has declined during the past four decades, researchers have been increasingly concerned about the degree to which parents are involved (or uninvolved) in their children’s education” (p. 202). These evidences alone make the case for why improving parent and family involvement is a significant issue deserving an immediate response. Literature Review Because I am focusing this essay on how to connect with and involve the parents and families of English Language Learners in their children’s literacy education at the early elementary level, my literature review is heavily concentrated on three main themes. The first theme that I will focus on is how involvement looks different across different cultures and contexts. Involvement can mean something entirely different to one family than it does to another and this is especially important to focus on when working with students from diverse backgrounds. The second theme that I will focus on is in relation to the factors that often inhibit involvement from occurring. In urban contexts especially, there are often a great deal of obstacles to getting parents and families involved, and as an educator, it is important to be aware of both the meaningful contributions and the perceived shortcomings of the population in which you are working in order to best meet their needs. Finally, I will focus on how this information can actually be implemented and discuss promising practices based on the research literature. Parent and Family Involvement Across Diverse Cultures But what exactly constitutes parent and family involvement? Involvement can look very distinctive across different cultures (Hutsinger & Jose, 2009), and traditional views of parental involvement are often times particularly challenging for immigrant and linguistically diverse BRIDGING THE GAP 9 parents (Araujo, 2009). Araujo (2009) states, “For many parents, especially those from an array of diverse cultures, involvement signifies instilling values, providing and taking care of their children, talking with them, and sending them to school clean, rested, and well fed” (p. 117). It is important to remember that involvement does not always mean parents volunteering in school committees and organizations. There are countless ways in which parents and families can be involved in their child’s education and it is imperative that we rethink our definitions of parent and family involvement and reconceptualize our views so that we are meeting the needs of families from all cultural backgrounds. Fry (2008) projected that by the year 2020, children of immigrants who will likely require ELL student services will number 17.9 million. It is necessary that schools address ways in which they can effectively serve linguistically diverse students and their families in order for these children to be successful. Factors Inhibiting Parent and Family Involvement Often times, the generalization is made that parents and families in urban and highly diverse contexts, who are often times less-educated, do not want to become involved in their children’s education (Epstein and Dauber, 1991). On the contrary, it is frequently the case that parents want to be involved they just do not know how. Epstein and Dauber (1991) support this by stating, “When teachers help them, parents of all backgrounds can be involved productively” (p. 290). Factors inhibiting parental involvement for certain groups include but are not limited to: time pressures, high cost of living leading to longer work hours, language barriers, lack of financial resources, and a feeling of intimidation (Jeynes, 2010). According to Jeynes (2010), the presence of these factors “means that educators cannot assume that parents will attend the standard parent-teacher meetings and the typical assemblies” (p. 763). One poll conducted in New Jersey even found that urban and minority parents are far more likely to feel unwelcome in BRIDGING THE GAP 10 their children’s schools (Barton, 2003, p. 20). Educators need to be sensitive to the challenges that many parents today face if they expect the level of parent and family involvement to be increased. Implementation Some of the best practices when working with linguistically diverse families include incorporating students’ funds of knowledge, implementing culturally relevant teaching, communicating with families, and seeking and extending assistance (Araujo, 2009, Moll et. al, 1992). Many students use lessons taught at home to navigate the school system (Araujo, 2009), and it is irrefutably important to be aware of the different ways in which families are already assisting children at home. When looking at promising practices for connecting with and involving the parents of English Language Learners in their children’s literacy education, I used Epstein’s (1995) framework of six types of involvement to organize these practices. The six types of involvement that I will describe below are: parenting, communicating, volunteering, learning at home, decision-making, and collaborating with community. Parenting. Epstein (1995) suggests that there are six types of involvement with the first being parenting and the basic obligations of families. This type of involvement is about helping families to establish positive home conditions which support children’s academic achievement (Huntsinger and Jose, 2009; Epstein & Dauber, 1991). Promising practices that fall under this category include holding workshops for parents at school or other locations, providing information to parents and families on specific skills required of students and how to assist children at home with learning activities, and helping families to understand when and how to make decisions about school programs and opportunities (Epstein, 1995). Epstein (1995) also BRIDGING THE GAP 11 suggests offering family support programs to assist with health and nutrition and providing ideas about how to monitor, discuss, and help with homework. When providing family support programs, research has shown the importance of ensuring that events have a specific purpose (Giles, 2006). People will be more likely to attend events if they believe that they are getting something out of it. In one study, a teacher explained that the principal recognized that the parents’ and families’ time was valuable as she stated, “We don’t do meaningless, little group things together. When they get together, it’s for a purpose; it’s an agenda; it’s a concern; it’s a planned activity” (Giles, 2006, p. 274). In order to maximize success, schools should determine the specific information that parents desire and plan accordingly. This information can be collected in the form of a short poll, survey, or even simply by asking. Most importantly, it is essential that the information that is being given is actually received and able to be understood by all parents and families. Communicating. Communication is key to parent and family involvement. Promising practices in this category include ways to communicate with families about school programs and children’s progress and ensure that all information is accessible, relevant, and able to be understood by all families (Epstein, 1995). In order to increase communication, Epstein (1995) suggests that teachers develop an awareness of their ability to communicate clearly and to appreciate the use of parent networks. Epstein (1995) also recommends that teachers work to understand family views on children’s programs and progress. When working towards improving communication between home and school, home visits are one way for teachers to learn more about student’s lives outside of the classroom. From reading literature on this topic, I have gathered the importance of establishing trust and rapport with the family during these visits in order for the necessary and effective exchange of BRIDGING THE GAP 12 information to take place. Gonzalez et al. (2001) even states, “One outcome of respectful ethnographic talk is an increased sense of confianza, or mutual trust, as parents and teachers come to view one another in multidimensional terms” (p. 104). Gonzalez et al. (2001) also found that it is important for teachers to “develop a nonevaluative, nonjudgemental stance to the fieldwork they will be conducting” (p. 103). They go on to say that “We may not always agree with what we hear, but our role is to understand how others make sense of their lives” (p.103). If home visits are not a possibility or if a teacher does not feel comfortable visiting the homes of one of his or her students there are other ways to learn about students’ funds of knowledge, or prior awareness and experience (Moll et al., 1992). An alternate strategy to household visits that Gonzalez et al (2001) suggested was gathering information during “conversations between teachers and parents when parents were dropping off or picking up their children [from school]” (p. 70). Other promising practices for increasing communications include providing translators for occasions such as parent-teacher conferences, workshops, and other school events and translating documents that are sent home and posted around the school. Another strategy involves creating and sending home surveys and questionnaires in order to learn what is occurring at students’ homes and allow parent and family voices to be heard. Schools should try multiple forms of communication in order to inform parents and families about events and other school information including positive phone calls, e-mails, social media sites, texting, sending home monthly newsletters, and even personally inviting parents to attend regular events. It is important that educators remain aware of the factors that inhibit parents and families form involvement and accommodate accordingly. If there are parents who cannot read, make phone BRIDGING THE GAP 13 calls, talk to them in person, or ask other parents to share information with them. Whatever it takes, all families should know what is going on with regards to their child’s education. Volunteering. When Epstein (1995) speaks about involvement at school, she refers to it as “volunteering,” which she defines as “anyone who supports school goals and children’s learning or development in any way, at any place, and at any time not just during the school day and at the school building” (p. 705). One major way to get families involved in the school is by recruiting and training volunteers to be helpful towards school improvement efforts (Epstein, 1995). Some of Epstein’s (1995) suggestions for doing this include creating a parent room for volunteer work, meetings, and resources for families, sending out an “annual postcard survey to identify all available talents, times and locations of volunteers,” and providing opportunities for parents to become classroom volunteers or parent patrols to assist with safety and operation of school programs (Epstein, 1995, p. 704). Creating a family-like community atmosphere is another great way to increase family involvement in schools (Giles, 2006). This can be done by celebrating and promoting academic achievement in the form of learning celebrations for students, having a student of the month or parent of the month program, hosting an open house in the Fall, and planning quarterly assemblies. One principal in a study even celebrated the birthdays of both children and parents at monthly learning celebrations (Giles, 2006). Another great practice, especially at the early elementary level, is to have students create personal invitations to parents and family members on special events asking them to come (Giles, 2006). Other promising practices for helping families to become involved at the school are related to creating a strong sense that families belong and feel welcomed. There are several ways to do this such as by implementing open-door strategies that invite parents into the building BRIDGING THE GAP 14 (Giles, 2006) and simply treating families with love and kindness (Jeynes, 2010). According to Jeynes (2010): Few things will more inspire parents to become involved in educating their children than a belief that the teacher and the school staff love their child. Ultimately, if parents believe that this is the state of affairs, then they will trust and cooperate with the teacher (p. 757). Other ways to help families feel welcomed at the school involve creating visual displays reflective of all families in the school with photos and artifacts and having an administrator, volunteer, or parent serve as a greeter at the beginning and end of the day (Giles, 2006). The key element of this factor of involvement is creating an environment that best meets the families’ individual needs. Learning at Home. The next element is concerned with involvement in learning at home. This refers to providing information and ideas to families regarding how to help children with their learning outside of school (Huntsinger and Jose, 2009; Epstein & Dauber, 1991). This can include information about how to help with homework, how to read with your child, how and when to make decisions about school programs, and the skills required of students to pass each grade. Some strategies that Epstein (1995) suggests for increasing learning at home and helping parents to become aware of their child as a learner include creating a “regular schedule of homework that requires students to discuss and interact with families on what they are learning in class” (p. 704). Epstein (1995) also recommends that families participate in setting student goals each year so that they are better able to support and encourage their student at home. BRIDGING THE GAP 15 Decision-Making. The fifth type of involvement in Epstein’s (1995) model is about involvement in decision-making. This means giving parents and families a voice and taking their opinions into account when making school decisions. In a study looking at changes in leadership, one principal who was attempting to reform a “challenging urban elementary school” had great success when she established site-based decision-making teams (SBDM) that “empowered teachers and parents to codetermine both the future direction of the school and the means of achieving shared goals (Giles, 2006, p. 271). Other ways to include parents in school decisions include creating an active PTA/PTO or other similar parent organizations and committees (Epstein, 1995). Epstein (1995) suggests giving parents leadership positions and opportunities for active participation where they can be “a real representative, with opportunities and support to hear from and communicate with other families” (p. 705). Epstein (1995) also mentions the importance of including parent leaders from all racial, ethnic, socioeconomic, and other groups in the school so that representatives from a variety of families are involved in the decision-making process. Other simple ways to ensure that parents and families have a voice in school decisions include sending home surveys, asking parents to take polls, and simply providing networks to link all families with parent representatives. Collaborating with Community. The final type of involvement is collaborating with the community. Epstein and Dauber (1991) state that this type of involvement includes “connections with agencies, businesses, and other groups that share responsibility for children’s education and future success (p. 291). Noguera and Wells (2001) support this with their belief that successful school reform cannot occur without all sectors of the community being involved in education. In order to strengthen this area of involvement, schools should make it their goal to make strong connections with agencies and businesses that share responsibility for children’s education and BRIDGING THE GAP 16 future successes. Schools should form connections with community organizations as well as work to provide children and families access to community and support services such as afterschool care, health services, resources to support learning, and summer enrichment programs. Another promising practice for collaborating with the community seen throughout the literature is the idea of establishing a network of mentors for students. In a study conducted by Giles (2006), one principal who is described established a network of 25-30 mentors drawn from the school’s banking and local business partners “for those children who had no parents, or parents who for a variety of reasons were unable to support their children’s learning” (p. 273). Giles (2006) provided an explanation of the mentor program from one of the teachers at the school: They take them out. They do things different for them and they help them academically. And [when the students]…go on a trip…they’ll be their parent for them for the day. And academically it changed them because there’s nothing worse in the world than to have something going on in school and you’re the only one that doesn’t have a parent or a big brother or sister, that kid is happy (p. 274). Basically, the essential piece of increasing family involvement by collaborating with the community is about seeking out appropriate resources and supports in order to form partnerships between community organizations and families that are mutually beneficial. Implications and Conclusions It would be extremely difficult to deny the fact that parent and family involvement is an important issue, specifically in urban and highly diverse contexts. While involvement may not look the same in all contexts, there are many different types of involvement and countless ways BRIDGING THE GAP 17 for parents and families to become active members in their children’s education. Most parents simply need help knowing how to be productively involved with the school (Epstein and Dauber, 1991). Epstein and Dauber (1991) state, “ Educators and researchers often view minority families and families of educationally disadvantaged students in terms of their deficiencies. Often, however, the deficiencies lie in the school programs” (p. 301). They go on to provide data from their research supporting that “all of the inner-city schools are discovering that, regardless of where they started from, they can systematically improve their practices to involve the families they serve” (Epstein and Dauber, 1991, p. 301). I believe both of these to be incredibly bold and important statements. We need to stop trying to figure out what is wrong with the parents and families whom we serve and instead start developing solutions that better serve them and meet their needs appropriately. I believe that as educators we owe it to our students and their families to do everything in our power to ensure that they reach their full potential and achieve success. In order to move forward with this issue, professional development is certainly needed. In my opinion, the issues with parent and family involvement are not related to a lack of research, as there is a tremendous body of literature on parent and family involvement from multiple contexts and points of view. The issue rather, is that the information is not being utilized to its full potential. All educators need to have an understanding of the importance of parent and family involvement, the ways in which it can look different across different cultures, how to overcome factors that inhibit involvement from occurring, and most importantly, how to use it as practical knowledge and make parent and family involvement a successful reality. I believe that, ultimately, if all of these things occur and educators work to make the school a welcoming, safe, and nurturing environment for students and their families, the gap between BRIDGING THE GAP 18 home and school should begin to disappear. This in turn will lead to increased academic achievement for students and overall success. As Epstein (1995) boldly states, “The way schools care about children is reflected in the way schools care about children’s families” (p.192). BRIDGING THE GAP 19 References Araujo, B. (2009). Best practices in working with linguistically diverse families. Intervention in School and Clinic, 45(2), 116-123. Barton, P.E. (2003). Parsing the achievement gap: Baseline for tracking progress. Princeton, NJ. Educational Testing Services. Epstein, J., & Dauber, S. (1991). School programs and teacher practices of parent involvement in inner-city elementary and middle schools. The Elementary School Journal, 91(3), 289305. Epstein, J. (1995). School/family/community partnerships: Caring for the children we share. The Phi Delta Kappan, 76(9). 701-712 Fry, R. (2008). The role of schools in the English language learner achievement gap. Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center. Giles, C. (2006). Transformational leadership in challenging urban elementary schools: A role for parent involvement? Leadership and Policy in Schools, 5(3), 257-282. Gonzalez, N., McIntyre, E., Rosebery, A. (2001). Classroom diversity: Connecting curriculum to students’ lives. New Hampshire: Heinermann. Irvine, J. (2003). Educating teachers for diversity: Seeing with a cultural eye. New York: Teachers College Press. Hoover-Dempsey et. al (2005). Why do parents become involved? Research findings and implications. The Elementary School Journal, 106(2), 105-130. Huntsinger, C., & Jose, P. (2009). Parenal involvement in children's schooling: Different menaings in different cultures. Early Childhood Reserach Quarterly, 24, 398-410. Jeynes, W. (2003). A meta-analysis: The effects of parental involvement on minority children's academic achievement. Education and Urban Society, 35(2), 202-218. BRIDGING THE GAP 20 Jeynes, W. (2010). The salience of the subtle aspects of parental involvement and encouraging that involvement: Implications for school-based programs. Teachers College Record, 112(3), 747-774. Milner, H. R. (2012) But what is urban eduation? Urban Education, 47(3), 556-561. Moll, L. (1992). Funds of Knowledge for Teaching: Using qualitative approach to connect homes and classrooms. Theory into Practice, 31(2), 132-141. Noguera, P.A. & Wells, L. (2011). The politics of school reform: A broader and bolder approach for Newark. Berkley Review of Education, 2(1), 5-25. United Way of Metropolitan Nashville (2012). Read to Succeed. Retrieved from http://www.unitedwaynashville.org/community-work/read-to-succeed/ St. Luke’s Community House (2012). Mission. Retrieved from http://stlukescommunityhouse.org/