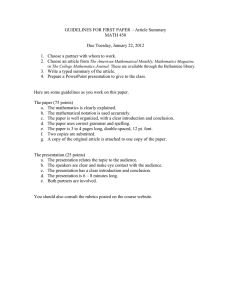

OsborneCapstone

advertisement

Running Head: BROADENING MATHEMATICS CURRICULUM Broadening Mathematics Curriculum: Linking Children’s Literature to Mathematics Sarah Osborne Vanderbilt University Summer 2011 BROADENING MATHEMATICS CURRICULUM 2 Abstract Children’s literature provides connections across all content areas. When incorporated within mathematics, it provides an engaging, accessible, and authentic context for learning. The literary experience can lead to mathematical investigations that address communication and problem solving skills, which are highly encouraged and stressed by both the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics(2011) and the Common Core Standards(2010). Student motivations along with development of conceptual understandings are instrumental in leading to academic success (Bransford et al., 2000). The use of children’s literature connects with the needs of learners to create transferable understandings by way of multiple contexts and exposures. These contexts need to be motivating and encouraging of students to be active learners. Students can thrive as learners when these activities occur within a collaborative, supportive, and challenging classroom environment. Children’s literature provides a necessary addition to mathematics curriculum by addressing problem solving and communication skills. Investigations allow teachers the opportunity to assess students in these domains. Resources for teachers exist on how and why to use literature, as well as resources for teachers to use in making evaluations on the literary qualities and mathematical soundness of children’s books (Whitin & Whitin, 2004, Schiro, 1997). Teachers can access many resources that offer suggestions for quality children’s literature and effective, connected mathematical activities (Burns, 1992). However, in a growing standards based curriculum the propensity to follow the textbook exists. The growing body of research and resources should be more accessible to teachers in order to encourage the effective use of children’s literature to create deeper conceptual based understandings through the use of communication and problem solving. BROADENING MATHEMATICS CURRICULUM 3 Broadening Mathematics Curriculums: Linking Children’s Literature to Mathematics Elementary mathematics education emphasizes the development of conceptual understandings. The Common Core Standards (2010) stress creating conceptual understanding of keys ideas, which often is not developed through the curriculum in current math textbooks. In addition, the Common Core Standards(2010) along with the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics(2011) put increased importance for students to be able to justify, orally communicate, and express through writing their understanding and comprehension of mathematics. It seems that these two important aspects of mathematics education align, and as teachers it is necessary to find instructional methods that align with and help students develop deep conceptual knowledge and abilities to express understandings. Many scholars and researchers including Marilyn Burns, Michael Schiro, and David and Phyllis Whitin promote children’s literature as an instructional tool for addressing these needs within mathematics education. Students’ academic development in math will not only benefit from the incorporation of children’s literature, but literacy development will also be simultaneously addressed. Tischler (1992) states, “Interdisciplinary studies not only save time but also add to children’s insight into all curriculum areas involved--the whole is greater than the sum of the parts”(p.1). Hong (1996) has found evidence that children benefit from the use of literature due to the familiar and meaningful context it can provide. Children’s literature provides a context and opportunity in which to have students reasoning, problem solving, communicating, and making connections within math and beyond. Whitin and Whitin (2004) state, “Literature is one way that mathematical ideas can be made more accessible to all learners”(p.86). The reasoning behind using literature in math is due to the positive implications it has for learners, the learning BROADENING MATHEMATICS CURRICULUM 4 environment, the curriculum, and the valid assessment of learning. All of these domains will be explored to see where the benefits on students’ mathematics and literacy development occur. The relevance and efficacy behind incorporating literature is further justified by the increasing amount of resources available for teachers to use to find connected, relevant and engaging texts. Addressing Principles of Learners and Learning Bransford, Brown, and Cocking (2010) state “the ultimate goal of schooling is to help students transfer what they have learned in school to everyday settings of home, community, and workplace”(p.73). In regards to mathematics curriculum, this goal can be achieved by developing transferable conceptual understandings. By looking at the strands within the Common Core Standards (2010) it is evident that knowledge needs to build and deepen from year to year. Tischler (1992) suggests the use of children’s literature as a means of supporting conceptual development. Using books as instructional tools can help lay the ground work for a conceptual understanding which is critical for students to be able to understand more advanced and abstract ideas. Literature also deepens and extends students learning of a concept. For transfer to occur it is important for students to be active participants while experiencing math in multiple contexts and modes. Tischler (1992) comments on the role of learners as active listeners, “When you read these books in the classroom, it is a challenge to keep students as actively involved as possible; do not let them become passive listeners. It may be appropriate to stop frequently and wait until all children have had a chance to think and respond to questions about the story”(p.63). This speaks to the dual role of both the teacher and the student in the learning process. Teachers have to create engaging and thought provoking lessons, but students also have to play an active role in the construction of knowledge. Furthermore, teachers take on the role of providing scaffolds for students learning. Teachers need to build a curriculum that BROADENING MATHEMATICS CURRICULUM 5 connects and builds off of students’ prior experiences and knowledge by showing explicitly or through scaffolding the connections between the subjects and the students’ everyday lives (Bransford et al., 2000). Children’s literature takes students out of the typical context of a math textbook. As discussed earlier, this supports the need for students to experience content in multiple contexts. Bransford et al. (2000) states, “knowledge that is taught in only a single context is less likely to support flexible transfer than knowledge that is taught in multiple contexts”(p.78). The benefits go beyond just providing another avenue for learning. Burns and Silbey (2000) report “stories that engage and delight can make mathematical ideas accessible, interesting, even compelling for children”(p.79). The authentic and relatable context children’s literature provides makes learning more accessible and meaningful. Ward’s (2005) work with mathematics pedagogy showed that students’ attention and interest is strongly captured through the use of literature and the real world connections it can provide. Bransford et al. (2000) emphasize the critical role motivation has on the extent and amount of time students devote to learning. In regards to learning activities, Bransford et al. states, “challenges, however, must be at the proper level of difficulty in order to be and to remain motivating: tasks that are too easy become boring, tasks that are too difficult cause frustration” (p.61). The above speaks to the necessity of scaffolding learning. Teachers need to create and maintain students interest, along with maintaining goals and student motivation (Bransford et al., 2000). The above discussion focused predominantly on increasing student learning in general and within mathematics, but as Ward (2000) found “literature also provides a means for mathematics and language skills to develop simultaneously as children learn to listen, read, write, and talk about mathematics”(133). Burns and Silbey (2000) recommend math teachers use BROADENING MATHEMATICS CURRICULUM 6 children’s literature within all grade levels and as a way to show the integration of subjects. Schiro’s (1997) research into the instructional technique of mathematical literary criticism shows the benefits to students’ development in both subject domains. The methods within this technique also put in place elements of scaffolding and motivation for students by creating a challenging task. The four phase method used within mathematical literary criticism involves students finding a meaningful problem within the story, developing plans to solve the problem, executing the plan, and lastly evaluating and reflecting on the effectiveness of the plan (Schiro, 1997). This is one method of using literature within mathematics that creates an authentic and meaningful learning experience. A Learning Environment that Supports Literature in Mathematics As discussed above, students learn best in academic settings that foster engagement through multiple contexts, accessibility, and an expectation that students will be active learners. These learning situations have to be supported by the context of the classroom. Bransford et al. (2000) state, “the learning environment is critical for determining what is learned”(p.94). Children’s literature promotes understanding in a way that is motivating for students if executed within a strong classroom community that supports learning in this manner. As discussed previously, the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (2011), promotes the use of communication and problem solving within mathematics. Teachers have to establish within their classroom an atmosphere of community where mathematics is valued and students feel they have the ability to be problem solvers. This is done through activities that promote the relevance of mathematics in students’ lives. Literature puts mathematics into an authentic context that students can relate to. Problem based scenarios that put students in the role of a mathematician create a collaborative classroom community environment. These scenarios along with the use of BROADENING MATHEMATICS CURRICULUM 7 whole class discussions and requiring students to talk mathematically promotes a classroom environment where mathematical communication is necessary to be a successful, vital member. Schiro’s (1997) research and support of using literature in mathematics pedagogy has found that “language is performing a socio-cultural function when the class as a whole gradually develops a common mathematical way of thinking about the book. Here language allows children to participate in a classroom community involved in mathematical discourse and develop shared mathematical understandings with others in their classroom”(p.71). A collaborative, motivated classroom community is further enhanced by mathematics being relatable to students’ current and future lives. Students can see math is all around them in their everyday lives. Schiro (1997) states “children’s literature places mathematics in a familiar setting that children can identify with and which feels relevant and interesting to them”(p.10). Problem based activities that build off of a shared literature experience provide students with the opportunity to engage and work with their classmates. Bransford et al. (2000) states, “social opportunities also affect motivation. Feeling that one is contributing something to others appears to be especially motivating”(p.61). Schiro’s (1997) research would support that literature provides a situation where students see the applicability of math to their everyday lives. As students work to solve problems, they will use their intellects, as well as everyday experiences, to demonstrate and build their learning. This accessibility extends to all students, no matter race, gender or ethnicity. Hong (1996) states “children learn more effectively in a familiar setting and in a context that is meaningful for them”(p.479). Children’s literature puts students into a familiar context they see across subjects and grade levels. It is a resource they interact with, within the classroom and hopefully, outside of school. This meaningful experience will increase students’ motivation BROADENING MATHEMATICS CURRICULUM 8 and involvement within the lesson. On the part of the teacher, it is important to consider if the level of math content present also matches the targeted audience as far as the content, themes, and literacy level of the books. As the teacher, it is necessary to make sure the context of the story and the math to be addressed complement each other in an authentic way. The connection should seem natural, but evident to the students. These factors will be important for creating an engaging and accessible lesson for all students. Other factors to consider when choosing texts will be discussed later on. The importance behind matching books to students’ abilities lies within the fact students need to feel success to be able to fully engage and participate within a classroom community. In a collaborative environment students will feel support and reinforcement in their efforts to comprehend and build knowledge. Curriculum and Instructional Strategies for Linking Literature and Mathematics The classroom community developed highly influences the effective execution of a successful curriculum. The shared experience children’s literature creates allows the development of a common classroom language and norms related to mathematics. Van De Walle (2010) supports that “children’s literature is a rich sources of problems at all levels, not just primary”(p.37). Reflective and problem-solving tasks can be developed from literature that extends up through the elementary grades. Burns and Silbey (2000) support as well that older elementary student still enjoy and learn from the use of literature. They have found that investigations can be built from stories, nonfiction texts such as The Guinness Book of World Records, and even chapter books provide mathematical grounded tasks and problems. Nonfiction texts provide great resources for students to learn about the world around them, alongside mathematics (Van De Walle, 2010). Tischler (1992) makes a strong argument that for “uppergrade students with limited reading skills, teachers might find that a book written for much BROADENING MATHEMATICS CURRICULUM 9 younger children can be refreshing and build confidence”(p.2). The importance lies in knowing the learners in the classroom, their needs, and their interests. Literature can be a source for reaching all of these within a mathematics curriculum and not just as a supplement but a source for conceptual development. Schiro (1997) offers further support for teachers using books as a means of instruction. The book provides the problem and students can even be prompted to find the mathematics within the story. This will help to develop students as critical thinkers in regards to both mathematics and literacy. Schiro (1997) offers support for even encouraging students to use literature that may have flaws in order to become critical readers and evaluators of the authenticity of the mathematics within the story. Students can even begin to correct and devise plans to improve what already exists to be more engaging and mathematically sound. Schiro (1997) coined this process as “mathematical literary criticism” which is “the process of examining children’s books with respect to a set of mathematical standards”(p.6). Despite the focus of this leaning towards critically looking at math content, there is a literary component too. Students are deeming the value of the literary qualities of the book as well. The context provided by children’s literature promotes students’ communication both in regards to reading and talking about mathematics ideas and concepts. “Whitin and Whitin (1996) offered that literature can be used to engage students in meaningful conversations and investigations in mathematics, which serve as bridges for students to connect the abstract, symbolic language of mathematics to their own personal world”(Ward, 2005, p.133). Moyer’s (2000) research into students developing the ability to communicate mathematically found that the natural context of math problems within stories promotes students’ oral language skills. The importance of this aspect of students’ academic development is seen in the communication standards within mathematics (National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, 2011). To encourage communication, the mathematics BROADENING MATHEMATICS CURRICULUM 10 curriculum needs to contain tasks and resources that build connections, take into account student interest, and show the value of mathematics. Tischler (1992) shows through his resources that books can motivate students to use manipulatives in a way that shows the purpose and meaning behind the manipulative. Children’s literature can become an instrumental part of the curriculum through increasing understanding, interest, and motivation. However, teachers need to constantly remember just as one would evaluate a book before use during language arts or a literacy block, it is equally important to extensively evaluate texts before using them to support mathematics learning. Schiro (1997) states “suffice it to say that children’s books need to be not only mathematically sound but also ‘good books’ from a literary perspective”(p.76). Teachers have to keep in mind and look at the text and illustrations to make sure they are mathematically accurate, even down to the fine details. Other standards and ideas to consider when implementing a children’s book as part of the curriculum will follow (Schiro, 1997). Do the mathematical ideas flow and do both the text and pictures support the reader’s comprehension? Is the mathematics evident to the reader? How does the book present math? Is it seen as enjoyable and useful? Whitin and Whitin (2004) report that “good books are inclusive by valuing, portraying and drawing in readers of all ethnicities, cultures, and genders…books convey sound and accurate content and they promote healthy attitudes and dispositions about mathematics”(p.2). These are just some standards and ideas to consider when looking at children’s books and the usefulness they can have within the curriculum. To be a strong curriculum that gives students multiple access points and exposure to concepts and ideas, teachers need to consider and look beyond just the textbook. By keeping in mind the evaluation standards above, well-chosen books can be made a strong addition to the curriculum to not only build, but also extend conceptual BROADENING MATHEMATICS CURRICULUM 11 understandings. To read more about evaluation standards look to Schiro (1997) and Whitin & Whitin (2004). Assessing Students in All Domains As a teacher, extending beyond the textbook is sometimes challenging since they usually align with the standards needing to be covered. However, just as teachers have an obligation to cover the standards, an obligation to create engaging, motivating and transferable instructional tasks exists too. Formal and informal assessments have to constantly happen in regards to the state mandated standards. Children’s literature can work towards helping students meet academic benchmarks. Tischler (1992) notes that the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics calls for students to become mathematical problem solvers. Whereas in a textbook students are often supplied the concept or formula and given practice problems, children’s literature can provide direct problems within a story to pose to children. Another method involves teachers building an engaging investigation off the shared literary experience. Tischler (1992) suggests that if students are prompted to see connections between math and literature, they can be encouraged to become more independent investigators of problems within stories they read. The scenarios created from children’s literature not only promote problem-solving skills, but also places an increased importance on being able to communicate mathematically. The instructional activities allot assessment opportunities for teachers to informally and formally assess students thinking through use of oral and written communication methods. Standards expect students to be able to justify, reason, and express their understanding through written and oral communication (National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, 2011). Students need contexts and experiences beyond the textbook to be able to develop and explore their thought processes and abilities to show understanding. Schiro (1997) states, “at the core of mathematical activity is the ability to BROADENING MATHEMATICS CURRICULUM 12 think, reason, and problem solve like a mathematician”(p.11). This speaks strongly to the new emphasis on communication and conceptual understanding found within the Common Core Standards (2010) and National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (2011) standards. The problems posed through literature can lead to these types of experiences and skills. Children’s literature as part of a math curriculum should not be looked at just as an enrichment activity. This type of instructional task can have implications on both students’ mathematical conceptual development and literacy skills (Schiro, 1997). To perform these mathematical investigations students have to use comprehension and literacy skills to grasp the problem and effectively link the solution to the problem within the story. Moyer (2000) states, “opportunities for discourse in both reading and mathematics instruction promote children’s oral language skills as well as their ability to think and communicate mathematically”(p.246). Most importantly, students are being required to think critically and justify what they know and pose as a solution. Whitin and Whitin (2004) highlight in their book New Visions for Linking Literature and Mathematics, the “importance of reasoning and communicating effectively through writing, talking and graphic representation”(p. xiii). These skills have to be equally assessed and practiced with students. Students need to not only understand the concept, but also be able to explain it and show they understand it. Whitin and Whitin (2004) support that children’s literature provides a wide range of applicability across concepts and grade levels. If teachers purposefully choose books, they can create a mathematical and literary experience that has students growing in both content areas. Therefore, what types of assessments can come through using children’s literature to build mathematical understandings? Standards for reasoning and communication and the need for a conceptual understanding give justification for using the instructional technique of BROADENING MATHEMATICS CURRICULUM 13 children’s literature. Moyer and Mailley (2004) point out the importance of the discussions that follow investigations built off a story as a means of assessment. Teachers can assess both mathematical and literary understandings, in addition to oral communication skills. The oral component can be very telling of a student’s level of understanding. Moyer and Mailley (2004) also found that within the lower elementary grades the discussion period is a critical time for extending student learning since students abilities to express through writing are not as advanced. An engaging, shared literary experience allows for and promotes more discussion than a standard textbook. This aids in students’ abilities to communicate mathematically. This discussion period allows for more two-way communication between student and teacher. This plays into the idea that “feedback is fundamental to learning”(Bransford et al., 2000, p.154). Furthermore Bransford et al. (2000) states, “if the goal is to enhance understanding, it is not sufficient to provide assessments that focus primarily on memory for facts and formulas”(p. 154). The discussions and investigations provided within children’s literature get beyond application of formulas and work towards expression of conceptual and understanding of big ideas within the domain of a subject. The research Moyer and Mailley (2004) gathered was from the use of the book Inchworm and a Half, which supports a study of fractional concepts. They found, within this literaturemathematics connection, strong support for the investigation period where students are the problem solvers. “Although teacher-provided representations are important during instruction for learning the conventional aspects of representation (such as fractional symbols), allowing student-generated representations can enhance and deepen the meaning of fractions and other mathematics concepts for young children”(p. 248). As mentioned before, learners need to be active participants in building their understanding. If students work to create their own effective BROADENING MATHEMATICS CURRICULUM 14 methods, the transfer and development of knowledge will become more meaningful and accessible. The idea of accessibility is extremely important as shown through the Common Core Standards (2010) use of strands such as numbers and operations, measurement, algebraic thinking, etc. Students need to be able to carry their strategies and conceptual understandings with them from year to year as concepts become more challenging and abstract. Bransford et al. (2000) state “helping learners choose, adapt, and invent tools for solving problems is one way to facilitate transfer while also encouraging flexibility”(p. 78). Flexibility is extremely important since each classroom comes with a diverse set of students as far as learning style, culture, interests, and so forth. Students need an exploratory phase in order to begin the groundwork of creating a conceptual understanding. With children’s literature students simultaneously have the opportunity to increase their literacy skills. Students can create a broader understanding of comprehension and problem solving by receiving more exposure to books and by looking at them with a mathematical lens. With so many standards to cover in both subjects, the opportunity to assess both literacy and mathematics development at the same time should prove a valuable opportunity for teachers. Assessment is a constant concern and activity of the teacher. By providing students more opportunities to communicate and apply their knowledge, teachers can make more valid and influential assessments. Moving Forward: Resources, Directions, and Cautions for Educators The above portion demonstrated the role children’s literature can take in building learners’ understandings, creating a collaborative and supportive environment, building a stronger curriculum, and lastly making more valid assessments of students’ comprehension and communication skills. The remainder seeks to show how educators, parents and researchers can work to use children’s literature due to its positive impact on student learning. It provides a new, BROADENING MATHEMATICS CURRICULUM 15 engaging context that strives to meet students’ needs and interests. Teachers have a busy schedule and luckily, many researchers and former teachers have taken a look into the effects of literature on mathematics learning. From seeing positive results, many have created annotated bibliographies, lists by concept, and lesson plan ideas that incorporate mathematics learning by way of quality children’s literature. The first resource to be mentioned that categorizes by mathematics concept or strand is John Van De Walle, Karen Karp and Jennifer Bay-Williams’s (2008) Elementary and Middle School Mathematics. This is not only a great resource for teachers of mathematics in general but at the end of each chapter is a helpful section entitled “Literature Connections.” The books listed here align with the mathematical strand discussed in the chapter. These span age levels, while also providing different student interests. Marilyn Burns (1992) in conjunction with Rusty Bresser (1995) and Stephanie Sheffield (1995) have created a number of Math and Literature resources for teachers. These suggest quality books and lesson plan ideas that have previously been effectively implemented. Burns (1992) states as her reasoning for creating such resources, “incorporating children’s books into math instruction helps students experience the wonder possible in mathematical problem solving and helps them see a connection between mathematics and the imaginative ideas in books”(p. 1). Marilyn Burns created these out of a need she saw not being addressed through merely textbooks. Students’ ability to mathematically communicate both orally and through writing was a concern she believes can be being addressed by using children’s literature as an instrumental part of the curriculum. Her books span grade levels and concepts as well. The lesson plans supported and encouraged by Bresser (1995) show that older students can be challenged by mathematical tasks that stem from a simpler story. In addition, older elementary students continue to enjoy and be engaged while read to. Whitin and Whitin’s (2004) resource provides ideas and children’s BROADENING MATHEMATICS CURRICULUM 16 literature that is evaluated in terms of mathematical and English/language arts standards. The first portion provides teachers with suggestions for evaluation of texts based on inquiry, critical thinking, and diversity, along with connections to standards. The second portion provides an annotated list of quality children’s literature by the mathematical strands outlined within most standards. Despite all of these valuable resources, it is still the responsibility and duty of the teacher to assess a books value to his or her individual classroom, especially in regards to their academic level and interests. As stated in many of these resources, these are ideas and suggestions not a full curriculum. However, value is seen through many of these books stating their objectives of increasing conceptual understanding through the encouragement of broader and more communication oriented mathematics. Children’s literature integrated into a mathematics curriculum may be a new venture for many teachers. The resources above provide not only texts and lesson plans but reasoning, research and substantiation behind making children’s literature an integral part of the math curriculum. Cotti and Shiro (2004) look into the impact a teacher’s ideology has on his or her instructional methods. They found through their research that teachers, despite their varying beliefs, support use of literature in mathematics. The ideology of the teacher does influence the reasoning behind, use and goals he or she places on the incorporation of a piece of literature. No matter one’s beliefs on the nature of schooling and teaching, children’s literature has a place and use within a mathematics curriculum. Since the importance is to have the story be a natural part of the curriculum, it is important teacher’s acknowledge they do not have to use it in the exact way another teacher proposes. The value comes in the way a teacher finds it to be effective with his or her students and in the way he or she sees it aligning with curricular goals and assessments. Schiro (1997) supports the use of these resources as ideas and suggestions to BROADENING MATHEMATICS CURRICULUM 17 support and extend mathematical thinking. Furthermore, Schiro (1997) highlights that these can be helpful hints for teachers, parents and other adults. The importance for parents and other adults who interact with children to be aware of these resources and to use books in this manner is evidenced by success reported in Bransford et al.’s (2000) How People Learn text. The research in this text found “connection-making and scaffolding by parents to support children’s mathematical learning has also proved a successful intervention that has been mimicked in school settings”(p. 108). Burns and Silbey (2000) suggest pointing out to parents the parts in the books that are helpful. Children’s literature that directly connects to math often has additional resources in the front and back to describe concepts, vocabulary, as well as giving extension activities and questions. If teachers send home books, they should also include math vocabulary and related content parents should be aware of. These additions enhance the literature opportunity parents have with their child. Marilyn Burns (1992) cautions teachers to not get into a habit of mathematizing every book, it is equally important for students to continue to enjoy literary experiences for the sake of the story. The suggestion here then is to read a book once all the way through before connecting or digging into the mathematic content. Burns and Silbey (2000) further support reading the story once with the intention to let students have a rich literature experience. The introduction of a connected math activity could come prior to the second reading so as students can focus on both the story and the mathematical goals. Another method is to prompt students to think of problems to solve that relate to the story. The benefits of this method is that the problems posed are more in line with students’ interests while also providing a more accurate look at the extent of student abilities in regards to comprehension and problem solving. Schiro (1997) makes a strong argument for teachers and students to not necessarily discard a book that is not completely BROADENING MATHEMATICS CURRICULUM 18 mathematically sound and of excellent literary qualities. Value can be found in using these somewhat flawed books as a means to be able to better evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of other literature. In addition, students and teachers can use it as an investigation to find, edit, and suggest where further supports and explanations are needed. Children’s literature provides a springboard for a number of mathematical and literary investigations. Future Directions and Implications for Mathematics, Literature, and My Classroom Practices The argument for the use of children’s literature within a mathematics curriculum has been delved into extensively. As mentioned previously, there are many resources out there for teachers to access in order to make children’s literature a valuable and successful learning opportunity; however, these resources and researched-proven methods need to be further supported in mathematics teaching and methodology texts, as well as in teachers manuals for the required text for that grade level. By having suggestions for the use of children’s literature in these two resources, educators will be more inspired and confident in the efficacy of this practice. As a future educator, it is important to share effective strategies with colleagues. Creating resources for other instructors will be useful in encouraging the use of children’s literature and also creates the opportunity for the teacher to reflect on what went well and what could be improved. The use of children’s literature to develop mathematical understandings will be a consistent addition to my mathematics curriculum. In order to determine its efficacy, I will reflect on students’ engagement levels and abilities to build understandings through this context. To gather students’ thoughts on literature in math, surveys can be used, as well as reflective journal prompts. The journal prompts will also be an assessment of student learning and BROADENING MATHEMATICS CURRICULUM 19 disposition towards mathematics and literature. Lastly, having other teachers observe and critique lessons where I incorporate literature will help to improve and strengthen my practice. For the above to happen and be more easily achieved, more quality literature that links math to authentic, relevant scenarios needs to be created or identified. Further research into the successful use of particular books can be done. In addition to merely more literature, more multicultural perspectives need to be addressed so that all students can be reached. Kathy Short (2011) states “culturally relevant literature allows readers to ‘see themselves’ within a book and provides opportunities for linking cultural knowledge and experiences to story worlds”(p. 53). As a future educator, it will be important to keep in mind the evaluation standards mentioned in the Curriculum and Instructional Strategies for Linking Literature and Mathematics section of this paper, along with addressing if the book allows all students access. Sharing success with particular books to colleagues can prove beneficial in spreading the practice of using children’s literature throughout all subject domains. Conclusions The National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (2011) places an increased importance on the role of written and oral communication. Children’s literature has been supported and established as one avenue for addressing these important standards. Ward (2005) states “literature also provides a means for mathematics and language skills to develop simultaneously as children learn to listen, read, write, and talk about mathematics”(p. 133). The integration of these two subjects addresses both literacy and mathematics standards. Learners are successful when learning is put into engaging, motivating and authentic contexts. Student participation is increased if interests are accessed and therefore, they become active constructors of their knowledge leading to more conceptual and transferable understandings. The curriculum needs to BROADENING MATHEMATICS CURRICULUM 20 be supplemented with materials that allow students to be problem solvers, as well as encouraged to be communicators of their knowledge. Researchers in mathematics and literacy development, along with experienced classroom teachers, have acknowledged the usefulness children’s literature can have in other subject domains. Children’s literature in a mathematics curriculum promotes reasoning, communication, conceptual development, and problem solving. Resources currently exist for teachers’ access to find relevant literature to most mathematics concepts. Further support and research into effective mathematical activities related to children’s literature will prove to help in creating a more comprehensive mathematics curriculum that helps students to build conceptual understandings that will transfer to their everyday lives. BROADENING MATHEMATICS CURRICULUM 21 References Bransford, J., Brown, A., & Cocking, R. (2000). How people learn: brain, mind, experience, and school(Expanded ed.). Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press. Bresser, R. (1995). Math and literature. Sausalito, CA: Math Solutions Publications. Burns, M. (1995). Math and literature: (K-3).. Sausalito, CA: Math Solutions Publications. Burns, M., & Silbey, R. (2000). So you have to teach math? Sound Advice for K-6 Teachers. Sausalito: Math Solutions Publications. Common Core Standards Initiative (2010). Common Core State Standards for Mathematics. Retrieved from the Common Core State Standards Initiative website: http://www.corestandards.org/assets/CCSSI_Math%20Standards.pdf Cotti, R., & Schiro, M. (2004). Connecting teacher beliefs to the use of children's literature in the teaching of mathematics. Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education, 7, 329-356. Hong, H. (1996). Effects of mathematics learning through children's literature on math achievement and dispositional outcomes. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 11, 477-494. Moyer, P. (2000). Communicating mathematically: Children's literature as a natural connection. The Reading Teacher, 54(3), 246-255. Moyer, P., & Mailley, E. (2004). Inchworm and a half: Developing fraction and measurement concepts using mathematical representations. Teaching Children Mathematics, 244-252. National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. (2011). Standards and Focal Points. Retrieved from the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics website: http://www.nctm.org/standards/default.aspx BROADENING MATHEMATICS CURRICULUM 22 Pierce, M.E., & Fontaine, L.M. (2009). Designing vocabulary instruction in mathematics. Reading Teacher, 63(3), 239-244. Schiro, M. (1997). Integrating children's literature and mathematics in the classroom: children as meaning makers, problem solvers, and literary critics. New York: Teachers College Press. Sheffield, S. (1995). Math and literature: K-3 : book two. Sausalito, CA: Math Solutions Publications. Short, Kathy. (2011). Reading Literature in Elementary Classrooms. In S. Wolf, K. Coats, P. Enciso, and C. Jenkins’s (Ed.), Children’s and Young Adult Literature (pp. 48-62). New York: Routledge. Tischler, R. (1992). How to use children's literature to teach mathematics. Reston, VA: National Council Of Teachers Of Mathematics. Walle, J. A., Karp, K., & Williams, J. M. (2008). Elementary and middle school mathematics teaching developmentally (7th ed.). Boston: Pearson/Allyn and Bacon Publishers. Ward, R. (2005). Using children's literature to inspire K-8 preservice teachers' future mathematics pedagogy. The Reading Teacher, 59(2), 132-143. Whitin, D. J., & Whitin, P. (2004). New visions for linking literature and mathematics. Urbana, Ill.: National Council of Teachers of English.