Corn_moms_clean2[1].doc

advertisement

![Corn_moms_clean2[1].doc](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/015297753_1-5ffdfeba8f157e43000a40be860cf2c9-768x994.png)

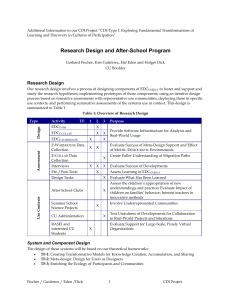

When Jesus Came, The Corn Mothers Went Away. Marriage, Sexuality and Power in New Mexico, 1500-1848. By Ramon A. Gutiérrez (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1991. Acknowledgements, contents, tables and figures, introduction, notes, bibliography, index. $68.95 hardcover) By using Jesus in the title of a book, an author might be attempting to convine his audience that the contents will be spiritually reassuring. Not necessarily so when Ramon Gutiérrez discusses Colonial Spain and its expansion into the American Southwest in his celebrated 1991 work, When Jesus Came, The Corn Mothers Went Away. Marriage, Sexuality and Power in New Mexico, 1500-1848. Gutiérrez does not use Jesus as the beginning of his story; rather he spins the web of the world’s origin according to Pueblo Indian folklore and then blends in the impact of Christianity and Spanish politics and culture on “one remote corner” of Spain’s Kingdom in New Mexico. (xvii) In juxtaposition, the book’s subtitle suggests that the forbidden pleasures of the flesh (by Catholic Church standards) have a significant role in his study. Recipient of several major historical association awards for this work, Gutiérrez has arranged When Jesus Came into three parts, by century, from the sixteenth through the eighteenth centuries. Individually the parts detail native culture, Spanish contact and conquest, and the eventual assimilation of cultures, respectively. Gutiérrez dedicates “The Sixteenth Century” to the Pueblo Indian world, opening a portal to the past through folklore legends of origins, transgression, absolution, and redemption. The mortar for the masonry of Puebloan society was sexual intercourse; it was synonymous with fertility and regeneration of the earth and “united all the masculine forces of the sky with the feminine forces of the earth.” (18) Part Two, “The Seventeenth Century,” details Spanish exploration and contact with native culture, including the events leading up to the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. When Jesus Came is also a study of misconceptions. Gutiérrez tells of the arrival of Spanish scout Estevanico, whom the Puebloans mistook for the return of the katsina—“the beneficent rain spirits that represented the ancestral dead”— which opened the door for Coronado’s arrival. (10) The predictable imposition of Spanish politics and ideologies followed. Gutiérrez is tireless at insisting that the Spaniards could not comprehend the key aspects of Puebloan society: gift giving and reciprocity and, most revolting to the missionaries, the significance of overt sexuality in Puebloan culture. Gutiérrez uses Part Three, “The Eighteenth Century,” to address the effects of Spain’s reconquest after the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. Gutiérrez also shifts his focus from the rural to the urban setting and emphasizes marriage as a scheme of social stratification. Honor becomes critical to the new society and Gutiérrez devotes much of this section to that honor, with special regard to status, virtue, and the church. The chapter “Marriage—The Empirical Evidence,” provides thorough statistics for the categorization of marriages by age, residence, race, and previous marital and slave status. Gutiérrez presents one chapter on the Bourbon Reforms, which attests to the lengths to which Spain was willing to extend itself in securing its place in the American Southwest. Gutiérrez outlines the economic, political, and religious aspects of the Bourbon Reforms, relative to the region, including increased taxes and trade restrictions, crown-appointed administrative officials, and the expulsion of the Jesuits from the area missions. Gutiérrez’ encapsulates the Pueblo Revolt in ten pages, which some scholars assess as an unforgivable oversight regarding this critical turning point in Puebloan history. We can excuse his brevity, however, only after reading the entire work. Gutiérrez provides us with such a comprehensive overview that we understand the Revolt is not focal to this study, rather it is just one, albeit critical, incident in whole of Puebloan history. Perhaps one-dimensional in his approach to gender (women as primarily sexual beings, women having higher value as slaves due to their reproductive capabilities), When Jesus Came could frustrate historians of women’s studies as Gutiérrez locks female Puebloan roles in the crosshairs of his narrow scope. He attempts, nonetheless, to view Puebloan society from a broad base of cultural factors, both pre- and post-Spanish influence. Gutiérrez demonstrates the scope of his research with extensive notes and a bibliography, including a “list of abbreviations.” However, the task of flipping pages to decode unfamiliar abbreviations while reading becomes tedious. Overall, When Jesus Came is a satisfying work that provides insight into pre-Spanish conquest Puebloan society and how cultures can first collide and then, although sometimes painfully, eventually blend. Gutiérrez has mastered the art of concocting a delectable feast of appreciation for the rich and exquisite Puebloan culture, one that existed before the Spanish added their contributions that forever altered the essence of an already perfectly balanced banquet.