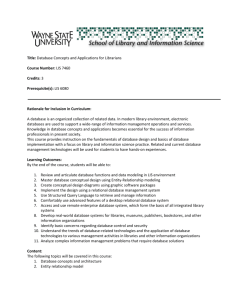

Handbook

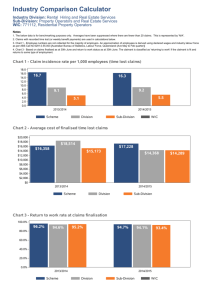

advertisement