Gotkin capstone essay

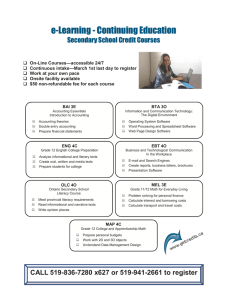

advertisement

Running head: SOCIAL MEDIA IN HIGH SCHOOL ENGLISH Academic Uses of Social Media Technology in the High School English Classroom Kelly Gotkin Peabody College, Vanderbilt University 1 SOCIAL MEDIA IN HIGH SCHOOL ENGLISH 2 Abstract The goal of this paper is to explore the potential uses of social media in high school English classrooms. Also explored is the reasoning behind integrating social media into the English curriculum. Social media use falls under the heading of digital literacies, but social media requires users to interact with each other, which sets it apart from non-social media such as PowerPoint presentations and computer word processing. Social media allows adolescents to perform multiple identities and to produce a wide variety of texts. Bringing these out-of-school practices into the classroom poses challenges for educators, though. Recent research begins to delve into how and why social media deserve a place in the classroom. Furthermore, educators may rely on case studies and practitioner reports to help fill in remaining gaps such as assessment of social media texts and processes. The paper explores how some teachers use social media to meet traditional goals of the English curriculum. Social media is a relatively new field, so there is also a discussion of some of its issues and implications of its future use. Keywords: social media, multiliteracies, digital literacy, new media Running head: SOCIAL MEDIA IN HIGH SCHOOL ENGLISH 3 Academic Uses of Social Media Technology in the High School English Classroom I hate writing stuff on paper because I feel like my hands can’t keep up with my thoughts when I write on paper. When I get to the end of the page with my pen, I feel like I lost my thoughts. I notice that I have more good thoughts when I’m on the Internet, clicking on stuff is more efficient than writing. I can get to everything I want on the Internet. If I click on Wikipedia I can get to what I want. I have more access to things like turtles…pet section. Plus online you can find a lot of other people who think the same thing you do. Google is my favorite thing. You can research forums and just anything. It expands my thinking more than books. (high school student A’idah as cited in Vasudevan, DeJaynes, & Schmier, 2010, p. 15) 21st century students live in an increasingly multimedia world. They process information that comes at them through television, the Internet, cell phones, computers, and an everexpanding list of electronic devices. Students then turn around and use these same technologies to produce unique texts. Up until recently, however, most in-school uses of technology have not taken advantage of students’ out-of-school knowledge regarding media. Classroom applications of technology have been largely limited to PowerPoint presentations, Internet searches, and computer word processing. To be sure, there are some inventive uses of new media in some classrooms, but this innovation needs to spread in order to benefit all students. The current, limited uses of technology mimic print literacies instead of capitalizing on what they have to offer in terms of innovation (Davies and Merchant, 2009). In order to best prepare students for life after graduation, though, these practices must evolve. The high school English classroom is already suited as a starting place for this evolution because so much of today’s technology involves navigating the nuances of language. The technologies that could earn a valid spot in English classrooms are numerous, but social media appear to lend themselves particularly well to the aims of English curricula. Merriam-Webster defines the scope of social media to the “forms of electronic communication (as Web sites for social networking and microblogging) through which users create online communities to share information, ideas, personal messages, and other Running head: SOCIAL MEDIA IN HIGH SCHOOL ENGLISH 4 content (as videos)” (n.d.). For example, blogs offer students the chance to practice “read- writethink- and –link” learning in which learning takes place through social participation (Richardson, 2006 as cited in Davies & Merchant, 2009, p. 31). By definition, high school English classes strive to teach students how to critically engage with all of the uses of language and symbol systems that surround them. Historically, this involved giving students the tools to read and respond to print texts. In today’s multimedia-driven world, however, restricting the English curriculum to print texts limits students’ abilities to interact with the wide range of print and nonprint texts that are now available. Social media has the potential to allow English educators to teach many of the print-related skills they always have while simultaneously teaching the newer skills required for success in the 21st century. The inclusion of social media in high school English also helps ensure that the curriculum remains relevant to students’ lives. English classes are most effective when they prepare students for the world that awaits and also surrounds them. At this point in time, that goal is difficult to achieve without the use of technology (Snyder & Bulfin, 2008). Social media offers English educators a chance to provide students with the multimedia skills they will need to succeed in academics, at work, in their personal lives, as citizens, etc. It also helps students see that in-school learning is not out of touch with out-ofschool literacy practices. Conceptual Framework The New London Group (1996) coined the term “multiliteracies” to cover “the multiplicity of communications channels and media, and the increasing saliency of cultural and linguistic diversity” (p. 63). The members of the group argue that literacy pedagogy has to adapt in the face of technologies that bring people from all over the world closer together in ways that were previously hard to imagine. In their view, people use languages and symbol systems to Running head: SOCIAL MEDIA IN HIGH SCHOOL ENGLISH 5 achieve cultural goals. In a world where technology plays an increasingly important role, new media become part of people’s cultures. Additionally, new media affect people so deeply that Lankshear and Knobel (2002) argue that they have led to the development of an “attention economy.” In an attention economy, teachers compete with a wide variety of other information sources for students’ attention. Without students’ attention, even the best designed curriculum is likely to fail. Educational settings, therefore, should not ignore new media. Students need to learn the skills to navigate differences in modes of communication, but it is up to the schools to make sure these skills have a place in the curriculum. The burden of bringing new media into classrooms rests with schools because “schools regulate access to orders of discourse – the relationship of discourses in a particular social space – to symbolic capital – symbolic meanings that have currency in access to employment, political power, and cultural recognition” (The New London Group, 1996, pp. 71-72). Even if students engage with new media in their out-of-school time, that engagement is not useful unless educators work to show students how to be critical consumers and producers of new media. Schools should incorporate social media, in particular, into the curriculum because they are technologies that most students already use, and because they have the potential to create new spaces for and types of learning (Davies & Merchant, 2009; Merchant, 2010). Technologies through which students can connect with each other have the potential to be educationally significant because they broaden students’ thinking both in and out of class. Keeping students engaged with content material even after school ends would be tremendous considering the rise of the “ten second attention span” produced by the attention economy (Lankshear & Knobel, 2002, p. 38). Social media also has the capacity to connect students from all over the world. This use of social media can help students begin to better understand how to navigate the Running head: SOCIAL MEDIA IN HIGH SCHOOL ENGLISH 6 differences in culture as noted by The New London Group (1996). Lastly, social media make it explicit to students that learning is not done in a vacuum. The potential of collaborative learning is not new to educators, but social media have the prospective to make those collaborations easier and more meaningful. Connections to the Classroom Learner Students today are what Marc Prensky (2001) termed “digital natives.” This label differentiates 21st century students from older generations because digital natives are the first students who cannot remember a time when technology did not play an important role in their lives. Digital immigrants, Prensky’s term for older media users, learned how to incorporate technology into their lives, but they have a pre-digital frame of reference that natives do not. Being digital natives puts today’s students in an interesting relationship with technology. Technology is vital to their lives, but most adolescents use new media without looking at it critically. Text or instant messaging is as natural to digital natives as picking up a landline to call a friend is for their parents. Media fluency is beneficial, though. As Susan Herring (2008) points out, “fluent young users who know their way around a range of information and communication technologies, can use them simultaneously (multitask), and are able to learn new ones quickly, technology is at their service – they shape (customize) it, rather than it shaping them” (p. 78). On the other hand, media savviness does come with drawbacks. Adolescents are less likely to see how media shape their world because of a “transparency problem” that prevents them from being able to contrast today’s technology with history’s lack of the same technology (Jenkins as cited in Herring, 2008, p. 88). This absence of historical perspective limits teens’ ability to critically view the new media that exists in their lives. The result of this media Running head: SOCIAL MEDIA IN HIGH SCHOOL ENGLISH 7 transparency is that many young people use social media without fully understanding the work they put into them. Adolescents may shape new media to perform unique functions, but those functions are not always clear to the people doing the shaping. Just as when people communicate face-to-face, social interaction via technology can serve numerous purposes. Technological interactions, however, carry some unique burdens because participants do not have cues such as facial expression and voice tone to rely on. Digital natives, then, use language and media in original ways to compensate for these missing aspects of communication. For example, in Lewis and Fabos’s (2005) study of a small group of teens’ use of instant messaging (IM) software, they discovered that the adolescents monitored and corrected spelling errors in their messages because correct spelling showed a certain level of perceived intelligence to their IM friends. Self-monitoring is a literacy skill promoted by teachers, but here the teens have unconsciously co-opted the skill and used it to help shape an online identity. Within the study, the adolescents also explained how they time their messages so as to not lose a thought or appear unpopular. Not immediately responding to a message implied that the person had other conversations going on. IM users, then, would wait to respond to a message even if they did not actually have something else requiring their attention. Once engaged in a particular conversation, though, the messenger would send numerous short messages so that the other person could not interrupt his/her thought. From this small example, it is easy to see how social media may encourage students to become deft linguistic manipulators. These skills come “naturally” to students, though, so they lack the critical ability to examine how and why they use new social media. Teaching students the metacognitive skills needed to examine their new literacy practices is part of showing students how to be reflective consumers and producers of social media. Running head: SOCIAL MEDIA IN HIGH SCHOOL ENGLISH 8 Social media play a prominent role in most 21st century adolescents’ lives because they offer powerful tools for young people to experiment with their identities due to the almost limitless opportunities for authorship. Students have the opportunity “to explore ways to present in public versions of themselves that may be stifled – for various reasons – in other settings” (Stern, 2008, p. 108). In this way, social media allow adolescents to explore and perform multiple identities. By varying what they publish via social technologies, a single young person may perform a broad range of identities (i.e. punk based on a list of favorite musicians, intelligent based on diction, rebel based on blog posts made about parents, etc.). Different identities may appear through different media, but the space provided by new technologies to explore multiple identities is important to adolescents. They may perform different identities for different audiences, and this use of media may be a rich area for educators to explore. For the most part, adolescents perform their multiple identities without realizing it. If educators could bring to light the differences in diction, voice, syntax, etc. that go into shaping various identities within social media, then students may develop a deeper understanding of themselves and of the different purposes that various media may serve. Learner Context It is, of course, essential that teachers understand that learning environment is as vital of an aspect of education as what individual prior knowledge students bring with them. For social media to have the greatest chance of academic success, there are steps that educators should take to create an optimal learner context. Davies and Merchant (2009) argue that four elements must be present for successful use of social media in classrooms: purpose, participation, partnerships, and planning (p. 106). The authors make the important point that simply providing students access to social technology is not enough to ensure that they will learn from it. In terms of Running head: SOCIAL MEDIA IN HIGH SCHOOL ENGLISH 9 purpose, teachers need to make explicit the functions that various social media serve. ChandlerOlcott and Mahar (2003) suggest having an overt discussion with students regarding “how information and communications technologies change people’s lives. In particular, they focus on the benefits and disadvantages of technology use for particular groups of people, as well as how those disadvantages might be overcome” (p. 361). This kind of conversation also feeds directly into the participation component of the learning environment because worthwhile academic uses of social technology broaden students’ learning communities. Allowing students to more freely share their thoughts and knowledge not just with each other, but also with authentic audiences outside school walls promotes a deeper understanding of how these social media work and their potential implications for life beyond the formal classroom. Naturally, closely connected to participation is the need for partnerships within the use of social media. Students tend to produce better work when writing for real audiences and not just their teacher. Therefore, it is the responsibility of the teacher to find “co-producers” with whom students can work (Davies & Merchant, 2009, p. 107). Co-producers encourage students to create higher quality texts because they have the opportunity to provide students with feedback and to use the students’ content to then generate their own works. Co-producers can be members of the same class, or they can be people from all over the world. They can be peers, or they can be adults and professionals of all ages and backgrounds. The far reach of social media enables teachers to truly be creative in choosing audiences for their students. The widely varied potential uses of social media do, however, also entail a great deal of planning on the part of the educator. Simply allowing students to roam the Internet or communicate with each other via cell phone or IM does not achieve any academic aims and is, therefore, not educationally beneficial. With careful planning, though, any of these technologies has the possibility to increase student Running head: SOCIAL MEDIA IN HIGH SCHOOL ENGLISH 10 learning. For example, in Mr. Cardenas’s urban middle school, members of his journalism and digital media studies class have a great deal of freedom, but that freedom comes with responsibilities (Vasudevan, DeJaynes, & Schmier, 2010). Students in the class may move around the school during the class period, have access to digital cameras and camcorders, and have fewer restrictions on how they navigate the Internet. In return for these freedoms, Mr. Cardenas requires a high caliber of reporting from his students. They have to “dig deeper” into their stories, and are pushed to produce new technology texts such as podcasts (p. 10). Mr. Cardenas’s class is much less structured than is the norm, but his students tend to perform better in his class than in most of their core classes. His class is an example of how carefully planned autonomy has the ability to empower students to embrace new technologies within the classroom and to use these media to meet high teacher expectations. Curriculum The New London Group (1996) outlines a multiliteracies pedagogy involving four parts: situated practice, overt instruction, critical framing, and transformed practice. These four components work in collaboration to enable students to learn not only how to consume and produce multimedia texts, but to also understand what each text can or cannot accomplish. The situated practice aspect of The New London Group’s pedagogy has many features in common with the participation and partnership components of learner context put forth by Davies and Merchant (2009). In addition to what is outlined above, The New London Group argues that situated practice should be part of a multiliteracies curriculum because “human knowledge […] is primarily situated in sociocultural settings and heavily contextualized in specific knowledge domains and practices” (1996, p. 84). This part of the curriculum should involve what literacy practices students bring to school because it will motivate students to learn and it will connect Running head: SOCIAL MEDIA IN HIGH SCHOOL ENGLISH 11 content to already existing student interests. For example, in the case of Mr. Cardenas’s class (Vasudevan, DeJaynes, & Schmier, 2010), he does not spend class time reviewing how various technologies work because he understands that most students come to his class with that information. His students appreciate this one lack of instruction as it shows that Mr. Cardenas respects his students’ out-of-school knowledge, and that he does not wish to waste anyone’s time. There are other moments, though, when Mr. Cardenas did need to teach his students new skills. Learning how to produce podcasts, in particular, required some explicit training. Overt instruction helps fill the gaps that simply immersing students in a situated practice cannot. Overt instruction is the purposeful use of scaffolding to encourage students to master new skills. Information covered by overt instruction should build on students’ prior knowledge and guide them to the creation of increasingly complex texts. A significant feature of this scaffolding process is the classroom teacher’s adoption of a metalanguage. Within multiliteracies, this metalanguage should enable students to discuss the “what” and “how” of literacy pedagogy, as well as “the form, content, and function of the discourses in practice” (The New London Group, 1996, p. 86). One of the main goals of these metalanguages is to provide students with the vocabulary to place their growing understanding of literacy within a historical and cultural framework. Critical framing of multiliteracies is essential because it allows students to distance themselves from their literacy practices. With enough distance, students can critique different literacies and develop a deeper comprehension of how diverse literacies play numerous roles within societies. Eventually, this critical approach to multiliteracies can potentially help students innovatively apply their knowledge to new and old learning communities (The New London Group, 1996). An illustration of how critical framing can work with social media is Merchant’s (2010) research on social networking sites (SNS). SNSs include popular websites such as Running head: SOCIAL MEDIA IN HIGH SCHOOL ENGLISH 12 Facebook and MySpace, as well as more broad categories of websites such as blogs and wikis. Merchant argues that teens’ use of SNSs could be important to educators because of the links made between literacy practices and identity performances. For adolescents to shape their identities on SNSs, they must consume and produce online texts. The production of texts is the social component of these websites because even if not directly responding to another user, teens choose what to post based on how they want others to perceive them. In his work, Merchant discovered that adolescents often discussed traditional literacies (such as books they enjoyed) on SNSs without any prompting. This kind of spontaneous conversation could be academically useful if teachers could provide a critical framing. Guiding students to understand how their SNS activities are part of their identity performance has the potential to add a layer of depth to teacher-prompted conversations on SNSs. Students can use SNSs to discuss traditional or nontraditional texts in new ways (overt instruction) through a medium in which most students are already involved (situated practice). Situated practice, overt instruction, and critical framing reach their culmination in the last component of the multiliteracies pedagogy: transformed practice. Transformed practice, very broadly, is situated practice revisited. After moving through situated practice, overt instruction, and critical framing, students now have the responsibility to demonstrate that their literacy practices have undergone reflexive changes (The New London Group, 1996, p. 87). Students have to show what new practice they have embedded in their original practices, but the teacher must provide the students with the opportunity to carry out this task. It is within transformed practice that teachers must assess student progress. The following section addresses the practicalities and challenges of assessing multiliteracy social texts and processes. Assessment Running head: SOCIAL MEDIA IN HIGH SCHOOL ENGLISH 13 Assessing texts produced with social media is a difficult task because there is little pedagogical research as to how to best go about doing it. Like any new text, though, educators can, and should, develop and revise assessment criteria over time. As more teachers make use of social media in their classrooms, more information will come to light as to what assessment strategies are more and less effective. This trial-and-error approach to assessment may intimidate some students and teachers, but it is a potentially invaluable aspect of The New London’s (1996) pedagogical cycle, as noted earlier. For now, teachers may develop their own assessments based on other practitioners’ experiences. One such experience comes from Tiffany DeJaynes (Vasudevan, DeJaynes, & Schmier, 2010), a technology-oriented English teacher from Brooklyn, NY. DeJaynes integrates technology in many ways, but her use of student blogs is one of the most prominent. The blogs primarily act as a free-write homework assignment that DeJaynes occasionally comments on or responds to. As far as assessment goes, DeJaynes grades the students’ blogs solely on completion. The focus on completion rather than on content resulted in students using the blogs to discuss anxieties, social interactions, current events, and even as a space to produce pieces of creative writing (Vasudevan, DeJaynes, & Schmier, 2010, p. 14). For DeJaynes, getting such a wide variety of self-generated writing topics from her students more than compensated for her decision to not to focus on traditional content concerns (grammar, spelling, organization, etc.). As a homework assignment, assessing for completion over content worked well for DeJaynes. Other assignments, with other academic goals, may require a different approach. Hicks (2009) offers strategies for more structured formative and summative assessments. For formative assessment, Hicks promotes the use of the MAPS framework: teachers and peers give feedback on Mode and media, Audience, Purpose, and Situation (p. 109). Social media Running head: SOCIAL MEDIA IN HIGH SCHOOL ENGLISH 14 such as blogs, IM software, and discussion boards allow students to receive feedback on their work in real time and on a continuous basis. Social media may make formative assessment easier because the length of the school day does not dictate the length of the assessment period, nor does the assessment have to be teacher-centered. All students can respond to texts posted on blogs, wikis, or SNSs, and this creates a richer sort of formative feedback because students are hearing from many perspectives, not just the teacher’s. The on-going nature of formative assessment also allows educators to focus on the processes involved in the use of social media. Students and teachers may respond to or provide constructive criticism for works in progress posted on SNSs, blogs, or wikis. Formative assessment is useful for ongoing projects such as class blogs and wikis, but social media can also play a role in summative assessment. To help connect digital writing to more conventional modes of writing, Hicks (2009) adopts the six trait writing model for use with digital texts. He argues for the use of the six trait rubric because it is one with which many teachers are familiar. Also, using the same rubric to assess digital and print texts may help students see the similarities between the two. Hicks also extends the educational uses of social media to encourage teachers to collaborate on assessments. He participated in a group of teachers who used Google Docs to help one teacher create and repeatedly revise a rubric for students’ blog writing. Nearly 50 teachers participated in the project and the Google Doc underwent almost 500 revisions over two years. This teacher’s assignment to his students was to blog, which is a use of social media, but the teacher himself also utilized a social medium to collaborate with colleagues about the best way(s) to assess the original assignment. The number of teachers involved in this endeavor and the number of revisions made to the rubric underscore what a difficult process assessment is. Through the use of social media, though, these teachers came together to promote social media in their Running head: SOCIAL MEDIA IN HIGH SCHOOL ENGLISH 15 classrooms and to make social media work for them. Rubrics are only one of a myriad of ways to do summative assessments, and the six trait model is only one rubric out of many. This small example, however, shows that assessing digital writing is not impossible. It, like any other classroom text production, has features and processes embedded within it that educators can use to develop their own approaches to formative and summative assessment. Assessment is also a realm in which students may become critical members of their own classroom practices. Students, as digital natives, may have perspectives as to what strategies concerning social media use in the classroom do or do not work. Teachers may wish to consider eliciting student feedback to inform future uses of new technology. Potential approaches to prompting student comments may include journal responses, exit slips, surveys, etc. Social media are not static and involve complicated practices, so it may be beneficial to seek student reactions before, during, and after a social media assignment. How frequently and to what depth teachers may want to consider student responses to social media will vary from classroom to classroom. In a world in which students may be the more proficient users, though, student feedback may be an important aspect of developing a curriculum that incorporates social media. The Future of Social Media in the Classroom The rapid rate of evolution within the realm of technology most likely means that digital literacies are here to stay. As more and newer technologies become a part of students’ lives, the more important it will be for these media to find a place in schools. The social media described above, blogs, wikis, IM, text messaging, etc., will most likely not exist as they do today for too many years to come. Some will evolve, some will find new purposes, and some will most likely disappear. That said, the unstable nature of social media should be more of a reason to integrate the technology into classrooms than to exclude it. Whether students leave high school to seek Running head: SOCIAL MEDIA IN HIGH SCHOOL ENGLISH 16 higher education or to enter the workforce, digital literacies will have some role in their futures. Even within the lives students live today, knowing how to critically consume and produce the media that surrounds them is an invaluable asset. Practitioner case studies and a growing body of research illustrate the potential benefits of using social media in the classroom. There are, however, many unanswered questions as to how to make this implementation most effective. Possibly most important is the need for further research into the best ways to assess students’ participation in social media. Teachers will need to work together to begin to identify features of effective social media texts and practices. How social media, and newer forms of digital literacy in general, can fit into state and national standards and tests is an even bigger obstacle that educators will need to face in the coming years. Of course, the issues surrounding the assessment of multiliteracies are moot if schools do not have the resources to bring the technology into the schools. Most schools today have Internet access and, in most cases, limited numbers of students have access to computers and other electronic devices at any one time. For social media to truly become part of students’ learning, improved access to technology is most likely vital. Education is a notoriously underfunded field, but to best prepare students for life beyond school, policy makers should investigate ways to help get technology into the hands of all students. Which technologies are worth investing in and which are fads that will quickly fade is not an easy distinction to make. There will most likely be an element of risk in schools spending large amounts of money on technology, but taking that risk has more of a chance of success than taking no risks at all. Additionally, teachers not familiar with newer technologies will probably need the support and resources to learn these new digital skills. This can take the form of a younger teacher explaining software to an older teacher, or it can take the more structured form of professional Running head: SOCIAL MEDIA IN HIGH SCHOOL ENGLISH 17 development courses. Regardless of what this training looks like, the most number of students will most likely benefit if the largest possible pool of teachers know how to effectively use technology in their classrooms. Social media, like most new curricular movements, come with their own issues and challenges. A central issue to the use of these technologies is concerns about student safety. Most people are aware of the horror stories that come from social media such as chat rooms and Facebook and that involve predators seeking out young people through these Internet sources. It is not highly likely that predators would seek out students through a class-mediated social medium, but there is some risk. Therefore, teachers may need to take steps to protect class uses of social media from full public viewing. Most blogs and wikis have the option of password protection and teachers may consider having students post using pseudonyms (teachers would keep a list of which student goes with which pseudonym to maintain accountability). Depending on individual teachers’ classroom settings, it may also be a good idea to seek parent permission for students to participate in online learning communities. How teachers handle the issue of safety will probably vary widely, but it is not an issue that educators can ignore. If managed diligently, though, it is likely that risk to students would not be a serious barrier to social media use in the classroom. Moving social media from students’ out-of-schools lives into their classrooms is by no means a quick or simple process, either. It does, though, appear to have the prospective of greatly benefitting students. The chances of helping to improve student achievement make investigating the possible educational uses of these technologies worthwhile. Social media are not entirely new technologies, but their migration into the world of education largely is. For that reason, case studies of how innovative teachers put them to work in their classrooms will most Running head: SOCIAL MEDIA IN HIGH SCHOOL ENGLISH 18 like be educators’ greatest resource until more thorough research comes to light. Published research as to possible ways to use these media comes out regularly, though, and as the presence of technology grows, it is probable that the amount of research into the subject will grow with it. Teachers will probably not see technology “trickle” into their classrooms; they will have to make conscious efforts to explore the media with their students. Reading professional journals, practicing trial and error, collaborating with peers (possibly through social media), and even taking the time to learn from tech-savvy students will most likely all prove beneficial to the use of social media in the classroom. This field changes rapidly and without warning, but to remain relevant, education must evolve alongside the technology that fuels its students. As a member of the millennial generation (people born after 1982, a cutoff date set by Howe and Strauss as quoted in Wilber, 2010, p. 8), social media plays a large role in my own life. On any given day I make use of text messages, blogs, discussion boards, Facebook, and Twitter. Knowing how important social media is to me means that I have some idea of how significant it is to students who are even more of a digital native than I am. Therefore, finding meaningful ways to make social media a part of my own high school English classroom is crucial to me. I want my pedagogy to be as relevant and authentic as possible, and in the 21st century that means seeking out ways to make use of new technologies. I want my students to practice traditional literacy skills (self-monitoring, questioning, predicting, metacognition, etc.), but I do not believe that these skills cannot also come into play with the use of new media. The extent to which I use social media once I become a teacher will most likely depend largely on where I teach. Schools and students do not have equal access to technology, so I will do my best to work with whatever I find in my individual situation. At the very least, though, I would like my students to work in some collaborative space such as a blog or wiki. Depending on how Running head: SOCIAL MEDIA IN HIGH SCHOOL ENGLISH 19 much technology is available, my classes may not have access to the blogs or wikis on a frequent basis, but I hope I can teach both traditional and new digital literacy skills even if I have to do so within a limited amount of time. My research into digital literacies associated with social media helped me see the potential benefits of working these technologies into my practice. I have a much deeper understanding of why I do what I do through various social media, and this knowledge is something I want to share with my students. For the most part, students will engage in social media whether or not it comes into the classroom, but if it does not come with them to school then they will most likely fail to achieve the depth of understanding that I have. I believe in the power of social media to help students learn and live productive lives, but I must work to ensure that I integrate social media into my classroom in ways that maximize the benefits for my students. I do not see technology as a magic bullet to fix the nation’s literacy woes, but I do see it as a potentially powerful means to that end. Running head: SOCIAL MEDIA IN HIGH SCHOOL ENGLISH 20 References Chandler-Olcott, K. & Mahar, D. (2003). “Tech-savviness” meets multiliteracies: Exploring adolescent girls’ technology-mediated literacy practices. Reading Research Quarterly, 38(3), 356-385. Davies, J. & Merchant, G. (2009). Web 2.0 for schools: Learning and social participation C. Lankshear, M. Knobel, & M. Peters, (Eds.). New York, NY: Peter Lang Publishing, Inc. Herring, S. C. (2008). Questioning the generational divide: Technological exoticism and adult constructions of online youth identity. In D. Buckingham (Ed.), Youth, identity, and digital media (pp. 71-92). Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. Hicks, T. (2009). The Digital Writing Workshop. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. Lankshear, C. & Knobel, M. (2002). Do we have your attention? New literacies, digital technologies, and the education of adolescents. In D. E. Alvermann (Ed.), Adolescents and literacies in a digital world (pp. 19-39). New York, NY: Peter Lang Publishing, Inc. Lewis, C. & Fabos, B. (2005). Instant messaging, literacies, and social identities. Reading Research Quarterly, 40(4), 470-501. Merchant, G. (2010). View my profile(s). In D. E. Alvermann (Ed.), Adolescents’ online literacies: Connecting classrooms, digital media, and popular culture (pp. 51-66). New York, NY: Peter Lang Publishing, Inc. The New London Group (1996). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard Educational Review, 66(1), 60-92. Prensky, M. (2001). Digital natives, digital immigrants. On the Horizon, 9(5), 1-6. Running head: SOCIAL MEDIA IN HIGH SCHOOL ENGLISH 21 Snyder, I. & Bulfin, S. (2008). Using new media in the secondary English classroom. In J. Coiro, M. Knobel, C. Lankshear, & D. J. Leu (Eds.), Handbook of research on new literacies (pp. 805-837). New York, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Social media. (n.d.). In Merriam-Webster Dictionary online. Retrieved from http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/social%20media Stern, S. (2008). Producing sites, exploring identities: Youth online authorship. In D. Buckingham (Ed.), Youth, identity, and digital media (pp. 95-117). Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. Vasudevan, L., DeJaynes, T., & Schmier, S. (2010). Multimodal pedagogies: Playing, teaching and learning with adolescents’ digital literacies. In D. E. Alvermann (Ed.), Adolescents’ online literacies: Connecting classrooms, digital media, and popular culture (pp. 5-22). New York, NY: Peter Lang Publishing, Inc. Wilber, D. J. (2010). iWrite: Using blogs, wikis, and digital stories in the English classroom. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. Running head: SOCIAL MEDIA IN HIGH SCHOOL ENGLISH 22 Appendix Social Medium Facebook Twitter Potential Educational Use Students create a profile page for a character or author. They have to justify what information that include/exclude Students craft a “Tweet stream” between two characters (i.e. Romeo and Juliet). The tweets can be in modern English, but the stream should demonstrate an understanding of the characteristics of the characters’ relationship 3. 4. 5. 6. Students use a class blog or individual blogs as journals in lieu of the traditional handwritten in-class journal blog wiki Students can use group wikis to collect information and collaborate on a group project. These wikis may be NCTE Standard(s) Covered Students apply a wide range of strategies to comprehend, interpret, evaluate, and appreciate texts. They draw on their prior experience, their interactions with other readers and writers, their knowledge of word meaning and of other texts, their word identification strategies, and their understanding of textual features (e.g., sound-letter correspondence, sentence structure, context, graphics). Students adjust their use of spoken, written, and visual language (e.g., conventions, style, vocabulary) to communicate effectively with a variety of audiences and for different purposes. Students employ a wide range of strategies as they write and use different writing process elements appropriately to communicate with different audiences for a variety of purposes. Students apply knowledge of language structure, language conventions (e.g., spelling and punctuation), media techniques, figurative language, and genre to create, critique, and discuss print and non-print texts. 4. Students adjust their use of spoken, written, and visual language (e.g., conventions, style, vocabulary) to communicate effectively with a variety of audiences and for different purposes. 5. Students employ a wide range of strategies as they write and use different writing process elements appropriately to communicate with different audiences for a variety of purposes. 7. Students conduct research on issues and interests by generating ideas and questions, and by posing problems. They gather, evaluate, and synthesize data from a variety of sources (e.g., print and non-print texts, Running head: SOCIAL MEDIA IN HIGH SCHOOL ENGLISH linked so that the entire class has access to all of the gathered information 23 artifacts, people) to communicate their discoveries in ways that suit their purpose and audience. 8. Students use a variety of technological and information resources (e.g., libraries, databases, computer networks, video) to gather and synthesize information and to create and communicate knowledge. instant message (IM) Students can use IM software to discuss class texts or work-in-progress. These discussions may take place in or out of school 11. Students participate as knowledgeable, reflective, creative, and critical members of a variety of literacy communities. NCTE standards retrieved from http://www.ncte.org/standards