Class Lecture Notes 22.doc

advertisement

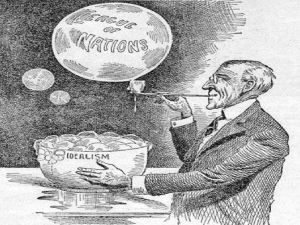

The American Promise – Lecture Notes Chapter 22 – World War I: The Progressive Crusade at Home and Abroad – 1914-1920 I. Woodrow Wilson and the World (Slide 2) Page 653 A. Taming the Americas 1. A New Foreign Policy—Wilson sought to distinguish his foreign policy from that of his Republican predecessors; thought their policies were crude flexing of military and economic muscle; appointed William Jennings Bryan, a pacifist, as secretary of state. 2. Maintaining the Monroe Doctrine—Wilson and Bryan, like Roosevelt and Taft, believed that the Monroe Doctrine gave the United States special rights and responsibilities in the Western Hemisphere; used it to justify U.S. action in Nicaragua, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic. 3. Involvement in Mexico—Wilson’s most serious and controversial involvement in Latin America occurred in Mexico; revolution broke out in 1910; General Victoriano Huerta seized power by violent means three years later; Wilson called them a “government of butchers”; sent 800 Marines to Veracruz and forced Huerta into exile. 4. Pancho Villa—The United States welcomed the government of Venustiano Carranza; prompted a rebellion among desperately poor farmers who believed that the new Mexican government, aided by American business interests, had betrayed the revolution’s promise to help the common people; a rebel army, led by Francisco “Pancho” Villa, attacked Americans and American interests; caused Wilson to send 12,000 troops to Mexico, only to withdraw them soon after to prepare for the possibility of fighting in World War I. B. The European Crisis Page 655 1. A Complex Web of Alliances—Before 1914, Europe enjoyed decades of peace, but beneath the surface lay the potentially destructive forces of nationalism and imperialism; European nations sought to avoid an explosion by establishing a complex web of military and diplomatic alliances: the Triple Alliance (Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy) opposed the Triple Entente, or the Allies (Great Britain, France, and Russia); efforts to prevent war through a balance of power only magnified the possibility of conflict. 2. Road to War—A Bosnian Serb terrorist assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, on June 28, 1914; within 1 of 10 The American Promise – Lecture Notes weeks, the elaborate alliance system turned a local conflict into an international one; war broke out in Europe. 3. A World War—The conflict escalated to a world war when Japan joined the cause against Germany; believed it could rid itself of European competition in China. C. The Ordeal of American Neutrality (Slide 6) Page 657 1. Declaring Neutrality—Wilson announced that the war was a European matter; engaged no vital American interest and involved no significant principle; announced that the United States would remain neutral; would continue normal relations with the warring nations. 2. American Sympathies—Although Wilson proclaimed neutrality, his sympathies, like those of many Americans, lay with Great Britain and France; shared a language and culture with Britain; France had helped in the American Revolution; Germany was a monarchy with militaristic traditions. 3. Testing Neutrality—Great Britain was the first to test America’s neutrality; used its navy to set up an economic blockade of Germany; America protested; Germany retaliated with a submarine blockade of British ports. 4. The Sinking of the Lusitania—On May 7, 1915, a German U-boat torpedoed the British passenger liner Lusitania, killing over 1,000 passengers, 128 of them U.S. citizens; attack provoked a mixed reaction from Americans; some demanded war, while others pointed out that the Lusitania was carrying munitions as well as passengers and was therefore a legitimate target. 5. Wilson’s Middle Course—Wilson’s response was to stay neutral, retaining his commitment to peace without condoning German attacks on passenger ships; Bryan resigned, predicting the president had placed the nation on a collision course with Germany; Germany apologized for the civilian deaths on the Lusitania and tensions subsided; Wilson’s middle-of-the-road strategy between aggressiveness and pacifism proved helpful in his bid for reelection in 1916; campaigned under the slogan “He kept us out of the war”; won by only 600,000 popular and 23 electoral votes. D. The United States Enters the War (Slide 9) Page 658 1. Siding with the Allies—Gradually, the United States backed away from “absolute neutrality” and became more forthrightly pro-Allies; by accepting the British blockade of Germany, the United States supplied Britain with 40 percent of their war materiel; also floated loans to Britain and France. 2 of 10 The American Promise – Lecture Notes 2. Submarine Warfare—In January 1917, the German government—resentful of neutral ships’ access to Great Britain while Britain’s blockade starved Germany— resumed unrestricted submarine warfare; hoped to win a military victory in France before the United States entered the war. 3. The Zimmerman Telegram—Wilson continued to hope for a negotiated peace but when the details of the Zimmerman telegram were released, revealing Germany’s attempt to ally itself with Mexico, it became increasingly more difficult for Wilson to pursue a policy of neutrality. 4. Entering the War—In March, German submarines sank five American vessels off Britain, killing 66 Americans and prompting Wilson to ask Congress for a declaration of war; an overwhelming majority voted in favor on April 5, 1917; among those voting no was Representative Jeanette Rankin of Montana, the first woman elected to Congress. II. “Over There” (Slide 10) Page 660 A. The Call to Arms 1. Struggle in Europe—When America entered the war, Britain and France were nearly exhausted after almost three years of conflict; another Allied power, Russia, was in turmoil, and the Bolshevik revolutionary government would eventually withdraw Russia from the war. 2. Raising an Army—On May 18, 1917, to meet the demand for fighting men, Wilson signed a Selective Service Act; authorized the draft of all young men into the armed forces; transformed a tiny volunteer armed force into a vast army and navy. 3. Black Soldiers—Of the 4.8 million men under arms, 370,000 were African Americans who had put aside their skepticism about the war to serve; during training, black recruits suffered the same prejudices they encountered in civilian life, facing abuse, segregation, and assignment to labor battalions. 4. A Progressive War—Progressives in the government were determined that training camps would turn out soldiers with the highest moral and civic values; asked soldiers to stop thinking about sex; Military Draft Act of 1917 prohibited prostitution and alcohol near training camps; Wilson chose John “Black Jack” Pershing to command the American Expeditionary Force; he was confident and had a morally upstanding reputation. 3 of 10 The American Promise – Lecture Notes B. The War in France (Slide 11) Page 662 1. Trench Warfare—At the front, the AEF discovered that the three-year-old war had degenerated into a stalemate; both the British and French armies had dug hundreds of miles of trenches across France, where both sides suffered tremendous casualties. 2. Black Troops’ Success in Battle—Except for the 92nd Division of black troops, which was integrated into the French army and fought for 191 days, American troops saw almost no combat in 1917; instead, they continued to train and explore places most of them otherwise could never have hoped to see. 3. Americans Enter Combat—The sightseeing and training ended in March 1918, when the signing of the Brest-Litovsk treaty took Russia out of the war; the Germans launched a massive offensive aimed at French ports on the Atlantic, causing 250,000 casualties on each side; the French agreed to General Pershing’s terms of a separate American command and in May 1918 assigned the Americans to the central sector; once committed, the Americans remained true to their way of waging war, checking the German advance with a series of dashing assaults. 4. Ending the War—In the summer of 1918, the Allies launched a massive counteroffensive that would end the war, routing German forces along the Marne River; German defenses held for six weeks; on November 11, 1918, an armistice was signed and the adventure of the AEF was over. 5. The Death Toll—Only the Civil War had been more costly in American lives, as 112,000 AEF soldiers perished from wounds and disease, while another 230,000 suffered casualties but survived; much worse for European nations: 2.2 million Germans, 1.9 million Russians, 1.4 million French, and 900,000 Britons. III. The Crusade for Democracy at Home (Slide 16) Page 663 A. The Progressive Stake in the War 1. War as Agent for Reform—The idea of war as an agent of social improvement reawakened the old zeal of the progressive movement; Washington soon bristled with hastily created agencies charged with managing the war effort; Bernard Baruch headed the War Industries Board and Herbert Hoover led the Food Administration. 2. The War and the Economy—Industrial leaders were encouraged by the tripling of corporate profits achieved by feats of production and efficiency; some working people also had cause to celebrate: Wartime agencies enacted the eight-hour workday, a living minimum wage, and collective bargaining rights in some industries; wages increased, but prices did as well. 4 of 10 The American Promise – Lecture Notes 3. Prohibition—The war also provided a huge boost to the stalled moral crusade to ban alcohol; prohibitionists eventually succeeded in securing the passage of a constitutional ban on alcohol, the Eighteenth Amendment, which went into effect on January 1, 1920. B. Women, War, and the Battle for Suffrage Page 665 1. Wartime Opportunities—The war presented women with new opportunities; more than 25,000 women served in France as nurses, ambulance drivers, canteen managers, and war correspondents; at home, long-standing barriers against hiring women fell when millions of working men became soldiers and few immigrant workers made it across the Atlantic; tens of thousands of women found work in defense plants and with the railroads. 2. Picketing the White House—The most dramatic advance for women came in the political arena; the radical wing of the suffragists, led by Alice Paul, picketed the White House; the more mainstream NAWSA, under the leadership of Carrie Chapman Catt, saw membership soar to some 2 million members. 3. The Nineteenth Amendment—Seeing the handwriting on the wall, the Republican and Progressive parties endorsed woman suffrage in 1916; in 1918, Wilson gave his support to suffrage, calling the amendment “vital to the winning of the war”; by August 1920, the states had ratified the Nineteenth Amendment, granting woman suffrage. C. Rally around the Flag—or Else (Slide 19) Page 666 1. Calling for Peace through Victory—When Congress finally committed the nation to war, most peace advocates rallied around the flag; only a handful of reformers, including settlement house leader Jane Addams, resisted bellicose patriotism in support of the war. 2. Encouraging Patriotism—Wilson stirred up patriotic fervor; in 1917, he created the Committee on Public Information (CPI) under the direction of muckraking journalist George Creel, who cheered on America’s war effort; sent the “FourMinute Men” around the country to give brief pep talks. 3. Demonizing the Germans—America rallied around Creel’s campaign, and a firestorm of anti-German passion swept the nation; the film industry cranked out melodramas and taught audiences to boo the German Kaiser; but as hysteria increased, the campaign reached absurd levels; in Montana, a school board barred a history text that had good things to say about medieval Germany; sauerkraut became liberty cabbage. 5 of 10 The American Promise – Lecture Notes 4. Suppressing Dissent—The Wilson administration’s zeal to suppress dissent took form in the Espionage Act, the Trading with the Enemy Act, and the Sedition Act, which gave the government sweeping powers to punish opinions or activities it considered “disloyal, profane, scurrilous or abusive”; contrasted sharply with the war’s aim of defending democracy. 5. Wartime Politics—Wilson hoped that national commitment to the war would subdue partisan politics, but Republican rivals used the war as a weapon against the Democrats; in the elections of 1918, Republicans won a narrow victory in both houses of Congress, ending Democratic control, suspending any possibility for further domestic reform, and dividing the leadership as U.S. forces advanced toward military victory. IV. A Compromised Peace (Slide 21) Page 668 A. Wilson’s Fourteen Points 1. A Blueprint for a New World Order—On January 8, 1918, President Wilson delivered a speech to Congress that revealed his vision of a generous peace; his Fourteen Points provided a blueprint for a new democratic world order; the first five points affirmed basic liberal ideas, and the next eight supported the right to self-determination of peoples who had been dominated by Germany. 2. A League of Nations—The fourteenth point called for a League of Nations to provide “mutual guarantees of political independence and territorial integrity to great and small states alike”; roused popular enthusiasm in the United States and every Allied country. B. The Paris Peace Conference 1. Wilson in Paris—Wilson decided to attend the Paris peace conference in person; as head of the American delegation; a risky decision, as his political opponents challenged his leadership at home; he further jeopardized his plans by stubbornly refusing to include prominent Republicans in the delegation. 2. Compromised Ideals—To the Allied leaders, Wilson appeared a naïve and impractical moralist; he did not understand hard European realities; Wilson was forced to make drastic compromises: in return for French moderation of territorial claims, Wilson agreed to support an article that assigned war guilt to Germany; many Germans felt as if their nation had been betrayed. 3. Self-Determination—Wilson had better success in establishing the principle of self-determination; the conference redrew the map of Europe and parts of the rest of the world; Wilson hoped that self-determination would also be the fate of Germany’s colonies in Asia and Africa, but the Allies who had taken over the 6 of 10 The American Promise – Lecture Notes colonies during the war only allowed the League of Nations a mandate to administer them. 4. Racial Equality Rejected—The cause of democratic equality suffered another setback when the peace conference refused to endorse Japan’s proposal for a clause in the treaty proclaiming the principle of racial equality; Wilson’s belief in the superiority of whites and his apprehension about how Americans would react to such a clause led him to reject the clause. 5. League of Nations—The issue that was closest to Wilson’s heart was finding a new way of managing international relations, an idea sketched out in his Fourteen Points; he was unwilling to see the world return to the old strategy of balance of power; Wilson proposed a League of Nations that would provide collective security and order; he was overjoyed when the Allies agreed to the League; to many Europeans and Americans whose hopes had been stirred by Wilson’s lofty aims, the Versailles treaty came as a bitter disappointment; the president dealt in compromise like any other politician; still, without Wilson’s presence, the treaty surely would have been more vindictive. C. The Fight for the Treaty (Slide 23) Page 672 1. Critics of the Versailles Treaty—The tumultuous reception Wilson received when he arrived home persuaded him, probably correctly, that the American people supported the treaty; by 1919, however, criticism was mounting, especially from Americans convinced that their countries of ethnic origin had not been given fair treatment. 2. Congressional Opposition—Wilson faced stiff opposition in the Senate from “irreconcilables,” who condemned the treaty for entangling the United States in world affairs, and from Republicans, who feared that membership in the League of Nations would jeopardize the nation’s independence. 3. Lodge’s Reservations—At the center of Republican opposition was Wilson’s archenemy, Senator Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts; used his position as chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee to air his complaints; out of committee hearings came several amendments, or “reservations,” that sought to limit the consequences of American involvement in the League; it became clear that ratification of the treaty depended on the acceptance of Lodge’s reservations, which the senator had appended to the treaty; but Wilson refused to accept the amendments. 4. Appeal to the People—Wilson decided to take his case directly to the people; embarked on an ambitious speaking tour; but he after three weeks he collapsed and had to return to Washington, where he suffered a massive stroke. 7 of 10 The American Promise – Lecture Notes 5. A Defeated Treaty—When the treaty without reservations came before the full Senate in March 1920, it came up six votes short of the two-thirds majority needed for passage; the nations of Europe went about organizing the League of Nations at Geneva, Switzerland, but the United States never became a member. V. Democracy at Risk (Slide 24) Page 673 A. Economic Hardship and Labor Upheaval 1. The Peacetime Economy—With the armistice came an urgent desire to return the United States to a peacetime economy, prompting the government to abandon its wartime controls on the economy and cancel defense contracts worth millions of dollars. 2. Rising Unemployment and Inflation—More than 3 million soldiers were released from the military, causing the unemployment rate to soar; at the same time, consumers went on a spending spree, causing inflation to soar; in 1919, prices rose 75 percent over prewar levels. 3. Worker Militancy—Most of the gains workers had made during the war evaporated; in 1919, there were 3,600 strikes involving 4 million workers; included a general strike in Seattle, the largest work stoppage in American history; a strike by Boston policemen brought out postwar hostility toward labor militancy in the public sector; labor strife reached its peak in the grim steel strike of 1919, where 18 strikers were killed; the strike collapsed, initiating a sharp decline in the fortunes of the labor movement, a trend that would continue for almost twenty years. B. The Red Scare (Slide 27) Page 675 1. Homegrown Causes—The “Red Scare” began in 1919; “Red” referred to the color of the Bolshevik flag; far outstripped the assault on civil liberties during the war; had homegrown causes: postwar recession, labor unrest, and the difficulties in reintegrating millions of returning veterans. 2. Influenza Epidemic—Two epidemics in 1918; Spanish influenza spread around the globe, and by the end of the outbreak, 40 million people died worldwide, including 700,000 Americans. 3. Rise of Communism—Russian bolshevism seemed to most Americans equally contagious and deadly; edgy Americans feared a Communist revolution in the United States. 8 of 10 The American Promise – Lecture Notes 4. Palmer Raids—Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer led an assault on alleged subversives; targeted those men and women who harbored what Palmer considered ideas that could lead to violence, even though they may have done nothing illegal; in January 1920, Palmer ordered a series of raids that netted 6,000 alleged subversives; effort to rid the country of alien radicals was matched by efforts to crush troublesome citizens; though he found no revolutionary conspiracies, he nonetheless ordered 500 noncitizen suspects, including Emma Goldman, deported. 5. A Public Attack on Civil Liberties—Law enforcement officials and vigilante groups joined hands in several cities and towns to rid themselves of so-called Reds; public institutions, including schools, libraries, and state legislatures, joined the attack on civil liberties; the Supreme Court acted to restrict free speech with its decision on Schenck v. United States. 6. Backlash—In 1920, the assault on civil liberties provoked the creation of the American Civil Liberties Union, which championed the targets of Palmer’s campaign; but in the end, the Red scare lost credibility and collapsed in its excesses once warnings of revolution never materialized. C. The Great Migrations of African Americans and Mexicans (Slide 28) Page 677 1. Escaping the South—In 1900, nine out ten blacks still lived in the South, where disfranchisement, segregation, and violence dominated their lives; World War I provided African Americans with the opportunity to escape the South’s cotton fields and kitchens; as the number of European immigrants fell, between 1915 and 1920, half a million blacks boarded trains for the industrial cities in the North. 2. Life in the North—Opportunities varied from city to city, but the North was not the promised land; many African Americans, including those who had fought in the war, suffered from job discrimination and racially motivated violence; 96 lynchings of blacks in 1918; still, most migrants who traveled to the North stayed and encouraged family and friends to follow; black enclaves developed in cities like Harlem in New York and the South Side of Chicago. 3. Mexican Immigration—Between 1910 and 1920, the Mexican-born population in the United States more than doubled; American racial stereotypes made Mexican immigrants prospects for manual labor but not for citizenship; by 1920, ethnic Mexicans made up about three-fourths of California’s farm laborers and were crucial to the Texas economy; Mexican immigrants in the Southwest dreamed of a better life in America; they found both opportunity and disappointment; despite friction, large-scale immigration into the Southwest meant a resurgence of the Mexican cultural presence, which in time became the basis for greater solidarity and political action for the ethnic Mexican population. 9 of 10 The American Promise – Lecture Notes D. Postwar Politics and the Election of 1920 Page 679 1. Continuing Wilsonian Policy—Wilson, suffering from the after-effects of a major stroke, insisted that the 1920 election would be a “solemn referendum” on the League of Nations; Democratic nominee James M. Cox of Ohio campaigned on Wilson’s international ideals. 2. A “Return to Normalcy”—Republican candidate, Ohio senator Warren G. Harding, showed little political aptitude but a great facility for connecting with the common people; won the election with the campaign promise to return the country to “normalcy”; achieved the largest presidential victory ever: 60.5 percent of the popular vote and 404 out of 531 electoral votes. 10 of 10