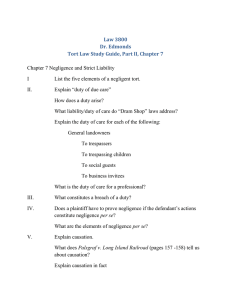

Fall 1999 Torts Outline I. Intentional Torts I. Intentional TortsI. Intentional Torts

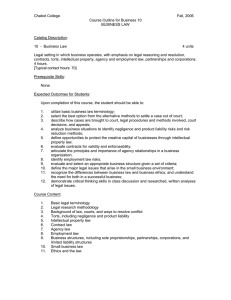

advertisement